Mar'20

The IUP Journal of Case Folio

Archives

Charity: Water ? Bringing Clean Water to the World?s Needy

Debapratim Purkayastha

Dean, IBS Case Research Center, IBS Hyderabad, Telangana, India. E-mail: debapratim@ibsindia.org

Tangirala Vijay Kumar

Freelancer, Hyderabad, Telangana, India. E-mail: research@icmrindia.org

The case discusses the work of Charity: Water (CW), a non-profit organization providing clean water to those lacking access to it. CW, which operated in 26 countries including several transition and conflict societies in the developing world, provided safe water by implementing diverse types of water projects, including wells. It focused on the raising of finances and collaborated with local organizations which executed the projects. This collaboration extended to taking inputs from the respective community members and partnering with the local and regional governments. The case highlights the three tenets to which CW adhered. The first tenet was that 100% of the public donations would be deployed in the execution of water projects. This routing of all public donations to the field was enabled by a group of wealthy individuals and families whose donations financed the organization?s overheads and salaries. The second tenet was that CW provided proof to each donor of how the donated amount was spent?the proof was in the form of photos and GPS coordinates on Google Maps of the water projects. The third tenet was that the organization employed technology-enabled storytelling to raise its profile and build its brand. It also innovatively engaged with its donors online, the result being that 70% of its donations were generated online. The case goes on to describe how CW ensured the sustainability of its interventions by developing and deploying sensors in the water projects. These sensors, which monitored the real-time flow of water, enabled the organization to foresee any breakdowns and send its technical crew to carry out repair works. The case discusses the impact of CW?s initiatives. The organization?s efforts provided over 8.4 million people in Africa, Latin America, and Asia access to safe and clean water. The provision of this essential service, besides improving the health of the beneficiaries, enabled them to focus on building their future. The case goes on to discuss the potential challenges faced by CW. Critics felt that other charitable organizations could emulate its innovative practices in online engagement and compete effectively for the same donations. Some key challenges before the organization were how to sustain the interest of its donors and raise the kind of mammoth resources required to reach out to every person in need of clean water.

At Charity: Water we are aiming to inspire a movement to solve the world water crisis. We do this by inspiring through storytelling, maximizing the impact people can make by sending every cent given or raised to fund water projects, and then by helping our supporters see their impact by linking their donation to a specific water project.

? Paull Young, Charity: Water?s then Director of Digital, in July 2012

Prior to getting access to clean water, Tencia, a single mom from a village in

Mozambique, spent half-a-day on a daily basis walking and queuing up to collect

water from a river outside her village. However, the water that she carried home was never sufficient for her family and she was left with barely any time to earn a livelihood. But after a hand-pump was installed at the center of her village by a non-profit organization called Charity: Water (CW), Tencia could bring home as much clean water as her family required. Moreover, she was left with ample time to pursue a bread-making business and work for her family?s future.ii

CW was founded by Scott Harrison (Harrison) in 2006 with the stated mission of bringing ?clean and safe drinking water to people in developing countries?.iii Operating in 26 countries, it acted primarily as a fundraising body and outsourced execution of water projects, including the digging and drilling of wells, to local partners. The water projects were implemented in collaboration with local governments, and inputs were garnered from the local community members when selecting the type of intervention. There were three tenets that CW adhered to. The first tenet was public donations were entirely used to finance the water projects?the overheads and salaries were financed by a group of wealthy individuals and families. The second tenet was that it provided proof to each donor of where his/her money was spent?the evidence was provided in the form of photos and GPS coordinates on Google Maps. CW?s third tenet was it tried to create an epic brand for itself by employing storytelling and maintaining an active presence on social media?70% of its donations were made online. It deployed technology to create what observers described as compelling stories of hope.

CW also developed sensors that were installed in its water projects. These sensors enabled it to monitor the flow of water and take quick remedial action in case the water flow was found to be reducing. According to observers, this contributed to the sustainability of the organization?s interventions. By January 2019, it had helped nearly 8.5 million people to gain access to safe and clean water. However, with other charitable organizations trying to catch up with it in innovatively engaging donors online, did CW?s fundraising prowess have a shelf life?

Background Note

Harrison, who grew up in New Jersey, had a relatively conservative upbringing. When he was four, his mother suffered from carbon monoxide poisoning due to a leak in their home. With his mother struggling with her health, a young Harrison became her cook and caretaker.iv After completing high school, he moved to New York to pursue a degree in communications. For 10 years, between the ages of 18 and 28, he had a successful career as a nightclub promoter. He, however, got hooked to various vices, including smoking, heavy drinking, gambling, and using drugs. One day in 2004, Harrison, who was holidaying with his friends in Uruguay, realized that he had become morally, spiritually, and emotionally bankrupt.

Harrison wanted to see what the exact opposite of his life would be; he quit all his vices and decided to work for a humanitarian organization. However, given his background, he was rejected by several humanitarian organizations. Finally, he was accepted as a volunteer by Mercy Ships, a faith-based fleet of floating hospitals that offered free medical aid to the poorest globally. Harrison had to pay US$500 every month and operate as a photojournalist, documenting the work of Mercy Ships.v

Harrison first sailed to Benin and then to Liberia, both in West Africa. It was in the course of this nearly-two-year assignment that he was exposed to the horrors emanating from the lack of access to safe and clean water. He saw women walk more than five hours every day to get water that made their children sick.vi He saw children drink dirty water from swamps, ponds, and rivers filled with algae and leeches. The result was children dying of diarrhea, giant tumors growing out of the heads and necks of men, and a flesh-eating disease called noma eating away at the lips, noses, and cheeks of children.vii

Harrison?s stint with Mercy Ships convinced him to start his own charitable organization to alleviate ?water poverty?. His rationale for tackling the problem of unsafe water was simple: Whereas problems such as cancer required cutting-edge research to eradicate them, a cure already existed for dirty water; frequently, clean water just had to be drilled from below people?s feet. Also, his visits to well sites in the course of volunteering with Mercy Ships convinced Harrison that there were remarkable organizations already operating in various countries to generate solutions such as hand-dug wells, deep-drilled wells, rainwater-harvesting mechanisms, and biosand filters costing merely US$60. If one was not focused on a specific type of intervention, one could resolve the issue of dirty water in several waysviii (Refer Exhibit I for details of the seriousness of the lack-of-access-to-safe-water problem).

Harrison launched CW on September 7, 2006, which happened to be his 31st birthday. Two days later, he threw a party at a trendy yet-to-be-opened nightclub in New York. He invited 700 guests from whom he charged US$20 each. He had the venue and booze sponsored through his connections from his earlier club-promoter days.ix He raised US$15,000 that night. He then took the money and went to a refugee camp in northern Uganda where he financed the building of three wells and the fixing of another three. These projects ensured that 30,000 people got access to clean water. Harrison then

e-mailed the photos and information about these projects to each of the guests who had attended his birthday party. ?Half of them couldn?t even remember being at the party but they were blown away by the pictures and the difference they had made. It was incredible. I knew then we were on to something?,x he recalled.

Operating Model

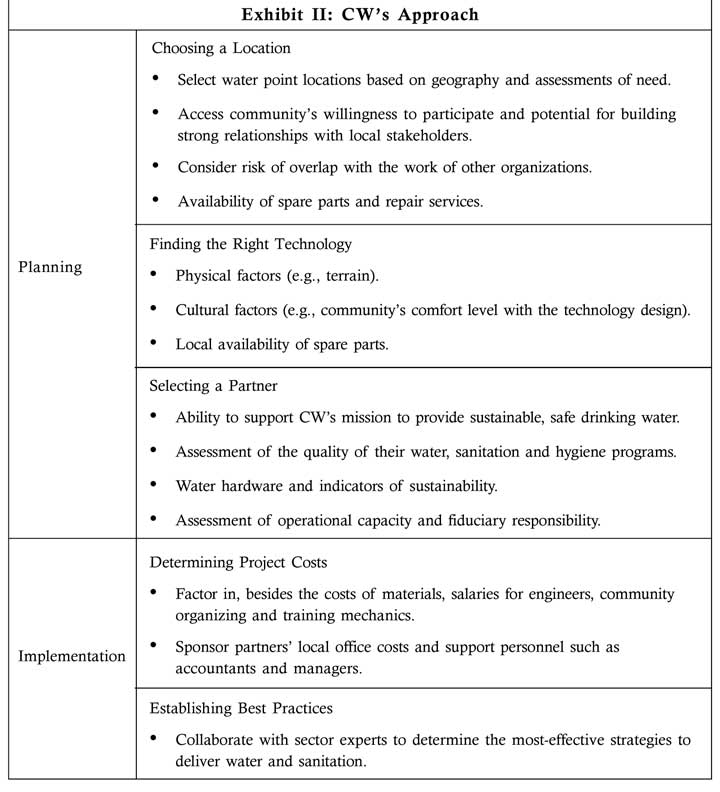

CW?s goal was to provide clean water to every person on earth lacking access to it. It operated in 26 countries spanning Africa, Latin America, and Asia. It did not drill wells or directly execute other waterworks. Instead, it operated as a fundraising clearinghouse for local organizations to which it subcontracted the actual execution.xi Its employees identified and oversaw the projects.xii With an increase in its capital, CW assumed a co-management role, supporting local partners with mapping, long-term planning, and strategic investing to ensure that those engaged in drilling, monitoring, and maintenance were well-equipped with machinery, staff, and training to expand in a manner that would enhance their impact (Refer Exhibit II for details of CW?s approach). Its Water Programs teams communicated with its local partners on a daily basis to monitor progress and troubleshoot issues that arose.xiii ?We would not send Westerners to Africa. We would find and build up local organizations, local partners. We would help the communities through their own local heroes,?xiv noted Harrison. He added that it was the organization?s belief that for the projects to be sustainable, the locals must lead them.xv

Exhibit I: The Gravity of the Lack-of-Access-to-Safe-Water Problem

Nearly three in ten people globally, or 2.1 billion, do not have access to safe, readily available water at home. Of these, 2.1 billion people, 844 million lack access to even a basic drinking water service. And of these, 844 million, 263 million devote more than 30 minutes on each trip to collect water from outside the home and 159 million drink untreated water from surface water sources, such as streams and lakes. The consequence is that each year 361,000 children aged below five years die because of diarrhea. Contaminated water is also a reason for the transmission of diseases such as cholera, dysentery, hepatitis A, and typhoid.

CW financed 11 diverse solutions globally, selecting them based on what delivered the best results in a given territory-inputs were also taken from local community members to determine the best sustainable solution for each location. These solutions included hand-dug wells that accessed groundwater 50-feet deep and drilled wells up to 1,000 feet deep.xvi, xvii In Cambodia, however, a different solution was provided. The country had an ample amount of surface water but it was contaminated. Therefore, a better option was to equip people with biosand filters, which filtered out sand and gravel from the water, and a biological film that neutralized dangerous bacteria. In Tanzania, where the rainy season was short but intense, CW financed rainwater harvesting technologies that accumulated drinkable rainwater in sanitary holding tanks; people could then use this water during the dry season. In countries such as Rwanda and Nepal, gravity-fed systems were the most cost-efficient mechanisms to accumulate, safeguard, and then channelize clean water from springs to access points.xviii

With each water point that CW financed, its local partners coordinated sanitation and hygiene training and set up a local Water Committee to ensure an uninterrupted flow of water.xix In some countries, CW also constructed latrines; covered shelters offered safety and privacy to bathroom users.xx It also maintained the wells dug by other organizations.

Some of the factors that CW's partners took into account in choosing water point locations were the scope for fostering robust relationships with local stakeholders and the risk of overlap with the initiatives of other organizations. Besides, a community's readiness to chip in was crucial as robust programs needed buy-in and involvement to sustain the water points over a long period.xxi Local governments had a key role to play in keeping the water flowing. CW's partners worked with community, district, and regional leaders to plan out the waterworks that CW would finance. This reinforced local ownership and contributed to building local capabilities to sustain projects for several years.xxii In some instances, governments also contributed finances for the implementation of water projects. For instance, in Rwanda, the government joined hands with CW in building a network of pipes, taps, and reservoirs spanning 42 kilometers.

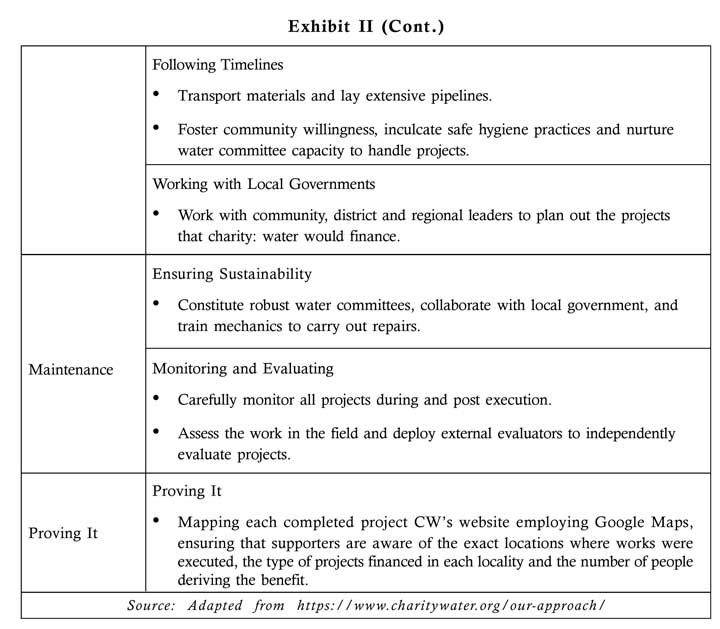

By March 2018, more than a million individuals had donated to CW.xxiii It received 70% of its donations online. For the year-ended December 31, 2017, the organization had generated revenue and other support of US$49.9 mn (Refer Exhibit III for CW's financial performance from 2012 to 2017).

Three Tenets

100% Model

The first tenet that CW followed was the '100% model'. Every penny from the public donations was used to finance water projects. To ensure that this rule was not violated, the organization opened two separate bank accounts-one to route all public donations directly to the field and the second to finance overheads, staff salaries, and supplies. Explaining the rationale for the '100% model', Harrison said, "People would constantly mention how they weren't sure if their money was going to the cause, or to other expenses."xxiv He added, "The problem we were trying to solve was to bring a group of people back to the table of giving who didn't trust charities."xxv CW was so particular about 100% of the public donations being used to finance water projects that it even reimbursed credit card transaction fees.xxvi For instance, if an individual donated US$100 using a credit card and CW received only US$97, it would contribute the US$3 and send the entire US$100 to the field.xxvii However, several charities were unhappy with CW for drawing donors' attention to the issue of overheads.

The operating expenses of CW were financed by a group of wealthy individuals and families who knew that their donations would not go to the field. These individuals and families, who were collectively referred to as 'The Well', donated between US$60,000 and US$1 mn per annum for at least three years. As of March 2018, The Well consisted of 125 members.xxviii Harrison devoted a major chunk of his time nurturing relationships with these members.

Transparency

The second tenet was that every donation, irrespective of the amount, was assigned to a specific project, and donors were given precise details of how their money was used. These details included photos, GPS coordinates on Google Maps, and sometimes even videos of the projects he/she had funded. "What is interesting is that, 18 months after donating to a project I am being given updates on where my donation was deployed and the effect it is having on the community. This is a huge change from traditional charity giving where, once you give, you forget,"xxix commented a member of The Well.

Explaining the level of transparency that CW believed in, an observer gave the following example: You were not merely helping drill a well, for instance, in Ethiopia-your money was used for the Ashala Wato community's project. CW went beyond that-you knew the precise project outlay (US$10,408.08), the local partner that built it (The International Rescue Committee), and you could view the photos of the well and the exact location by means of GPS.xxx "What caught my eye was the model of transparency. One hundred percent of what people give goes to the field and you can see what is happening, with the GPS coordinates and so on. I look at donations to charity as an investment and treat them like other investments, and Scott has a very tech approach to charity, delivering data and numbers. You can see a clear return,"xxxi remarked another member of The Well.

Epic Brand

The third tenet that CW followed was a constant endeavor on its part to create an epic brand for itself. Harrison explained, "to solve a problem as big as the water crisis, we would need to create an epic brand."xxxii To create a robust brand for itself in the world of philanthropy, the organization focused on emotional storytelling and brilliant websites that were easy to navigate.xxxiii The storytelling was primarily in the form of lively and inspiring videos-CW's supporters could easily post these videos on Facebook to share its work with others.xxxiv Observers pointed to one of the popular videos wherein well-to-do residents of Manhattan left their luxurious homes and queued up to fill jerricans with dirty water from a lake in Central Park. The audience then saw a mother providing the dirty water to her kids; the bullish message was that one could help ensure that a similar fate did not befall others either.xxxv Another striking ad showed baby bottles filled with dirty water.

In December of each year, CW organized a fundraising gala to raise a considerable amount of financial resources. According to observers, the organization was able to raise significant resources at these galas because of the deployment of cutting-edge technologies to create powerful narratives. One such technology that it used was virtual reality.1

Virtual Reality and Content Strategy

In December 2015, at the gala held in New York, CW unveiled a virtual reality documentary titled The Source. The documentary, which was shot on location in Ethiopia, depicted the situation in one of the local communities prior to the building of a well and the situation subsequent to that. It portrayed the everyday life of Salem, a girl aged 13 years. With a voice-over (done by an Ethiopian girl in English) narrating every scene, the audience viewed Salem collecting water containing leeches from a reservoir used by animals to drink and bathe. They watched her tending to her brothers and sisters in a rudimentary hut they referred to as home-her mother had died a year earlier.xxxvi The audience viewed her actively participating in school. They then saw the drilling rig and the team come to the location. And most importantly, they viewed the emotional moment when the drill struck water and Salem and her community got to drink clean water for the first time.xxxvii "I saw people take [their headsets] off with tears in their eyes,"xxxviii recalled Jamie Pent, CW's filmmaker. The audience donated US$2.4 mn that night to support an additional 240 villages.xxxix

Explaining the need for the use of virtual reality technology, Harrison said, "Shooting our film, The Source in VR (Virtual Reality) was an attempt to bring more people closer to the need on the ground, and the solutions..when people hear about 663 million people without clean water, they just kind of shut down emotionally. It's almost impossible for our brains to process numbers that big. But in those statistics are the lives of real people. People who are suffering without clean water."xl On a visit to CW's office, a donor, who had already promised a donation of US$60,000, viewed the documentary and was so moved by it that he donated US$400,000 instead.xli

In December 2016, at the annual gala, each of the guests was given an iPad with a password to unlock it. After Harrison talked about and showed a video of Adi Etot, Ethiopia, a nearly-400-strong community desperately requiring clean water, on a big screen, the guests were asked to unlock their respective iPads. Upon doing so, to each guest's surprise, the name and picture of a person from the Adi Etot community who was similar to him/her in terms of attributes such as gender and age were displayed. Pregnant guests were matched with expecting mothers from the community.xlii

After some time, a live video was broadcast from Adi Etot and displayed on the screen-the arrangement needed CW to work in coordination with the Ethiopian government authorities and its local partner that built the wells, the Relief Society of Tigray, which was located 100 miles away. The audience could see a rig drill the earth for water; the rig was surrounded by the local people whom the audience had just seen on the iPads. Once the drill hit the water and water sprayed out from the ground, the audience looked at the ecstatic faces of the locals and cheered as well. The guests donated around US$3.2 mn that night.xliii

Harrison also organized donor trips to project sites as narratives.xliv Instead of being given royal treatment, the high-profile donors were made to sleep in packed dorms, carry jerricans filled with water over long distances, and drive for hours on rough roads between villages.xlv Commenting on the impact of these trips, an observer wrote, "Experiencing a glimpse of hardship and being personally thanked by local villagers will inspire participants to not only donate money afterwards, but become ambassadors to their network of deep-pocketed friends and legions of Twitter followers."xlvi

A key facet of CW's storytelling strategy was the use of cheerful images of its subjects. Harrison explained, "When we started, the biggest problem was that my friends said giving to charity was really depressing. So we came up with some rules: No pictures of crying children or people with flies in their eyes. No using guilt or shame."xlvii Experts opined that the organization's use of positive images made potential donors feel excited and hopeful. Harrison added, "It should be cool to give. It should be cool to be generous. It should be cool to say yes to helping out."xlviii Paull Young (Young), CW's Director of Digital as of 2014 wrote, "In a traditional media world of one-to-many communication a tear-jerking commercial is an effective way to have you pull out your checkbook. But nobody is going to share a sad dog commercial with their friends and family on Facebook. In a model where inspiration is key, and a media environment where sharing wins, Opportunity not Guilt is critical for our content strategy."xlix

Digital Tools and Social Media Presence Observers opined that the digital tools that CW offered to its donors and potential donors also helped to increase the robustness of its brand in the world of philanthropy. These digital tools were in the form of the website, my.charitywater.org, and social media platforms; mycharitywater.org gave one the feel of being on a social network. On it, a person could set up a fundraising webpage and request his/her friends and family and friends of friends and family to donate for an event or a cause such as a birthday or a marathon.l The most popular form of donation on this platform was for people to give up their birthdays and ask their family and friends and social media contacts to donate a dollar per each year of their life rather than give gifts. The fundraisers as well as the donors could view in real time the amount of money raised and how it was spent. Several celebrities such as Will and Jada Smith, Alyssa Milano, Justin Bieber, and Jessica Biel had given up their birthdays and donated the money to CW. For instance, on Will Smith's 42nd birthday, he and his wife raised more than US$100,000 by requesting the public to donate US$42 each.li Tech CEOs also raised tens of thousands of dollars for each campaign by giving up their birthdays.lii Beyond raising finances, CW's online fundraising campaigns had a larger strategic objective. Young explained, "At charity: water, we attention on acquiring fundraisers because it is so much more valuable. While our average donation size online is similar to most charities I have benchmarked, our average fundraising campaign is worth many times more. But even more importantly, every fundraising campaign brings in, on average, 13 new donors."liii

CW had a strong social media presence. It was present on 10 different social media platforms because it wanted to be wherever its donors were and, as Harrison said, it was as simple as a sign-up. It was the first non-profit organization to register one million followers on Twitter. It had also created Twitter accounts for some of its well-drilling rigs-the ones that were crowdfunded-and it sent out regular updates on their progress.

According to observers, the transparency that CW maintained with its donors helped it to cement its reputation. Each year, CW broadcast live the drilling of a well. One year, that drilling failed to hit water. Harrison, however, made a video of the failed drilling and circulated it among the organization's supporters. He maintained that the instance of openness was among the organization's best accomplishments. "People just want to hear the truth,"liv he said.

Sustainability

In 2012, CW received a US$5 mn Global Impact Award grant from Googe.org to develop and install sensors to monitor and transmit water flow at its water projects. Explaining the need for the sensors, Christoph Gorder, CW's Chief Global Water Officer, said, "As we were growing up as an organization ... one of the challenges that we realized the industry faces was that after you build a water project and you train the local community on how to maintain it, there was very little information available on what happened afterwards. How long did it work? How much clean water did it provide? What was the impact on people's lives?"lv

CW took three years to develop the sensors and, by March 2017, it had installed 3,000 sensors in northern Ethiopia.lvi The sensors were made of food-grade plastic, implying that they wouldn't contaminate the water that flowed through them. Talking about the durability of the sensors, which were bombproof, Gorder remarked, "You could drive a truck over it and nothing would happen."lvii The lithium batteries deployed in the sensors would work for 12 years.lviii Also, the sensors were UV resistant and could withstand harsh heat conditions. They could be installed in a span of 10 minutes by any village pump technician with a standard wrench and two feet of rope. Each of the sensors cost merely around US$105.lix

CW garnered real-time data about the water flow and functionality of its water projects. The data generated by the sensor was transmitted from a universal mobile SIM and entered into an algorithm that assessed patterns and produced alerts in case there was a significant reduction in the water flow.lx The sensors, which were mainly deployed on hand pumps, informed the organization about the number of liters of water being utilized and the time of the day when the hand pumps were being utilized-something which it had not been able to gauge accurately earlier.lxi

In addition, the flow metrics signaled fluctuations in water flow and consumption. If water flow seemed to be waning, CW could inform local maintenance team crews and troubleshoot the issue. This helped in reducing downtime at water points when they required repairs. Prior to the sensors being deployed, it frequently took weeks and occasionally even months to reach out to remote locations and carry out repair works.lxii "..we'll also be able to look at patterns and predict breakdowns,"lxiii added Gorder. The data generated was shared with local governments and water bureaus and it enabled the authorities to understand water use in their own communities with an accuracy not achieved previously.lxiv

According to Harrison, the sensors offered an additional level of accountability and transparency as the donors not only knew the location of their well but were also aware of whether it was still operating after several years.lxv Giving an example, he wrote, "Today, I can call a donor who gave up her birthday seven years ago and say, "Hey, Gelila, do you want to know how some of your wells are doing? Let's check in on one of them." We can zoom in on her well, pull up a photo and GPS, and see that, on Tuesday of this week, more than a thousand gallons of clean water came out of the well-a well built for her birthday seven years ago."lxvi The sensor design and firmware were open source; hence, a user could go to CW's website and download the schematics.lxvii

Challenging the Stereotypes

Observers commended CW for going against some of the well-entrenched beliefs such as the perception that non-profit organizations should not expend much on overheads such as office spaces. "From advertising campaigns on 5th avenue, fancy galas, and magnificent office spaces, charity: water hasn't shied away from spending on things that are valuable to their work,"lxviii commented an observer. As proof, he pointed at the organization's gorgeous office in New York. "We think our staff is our greatest asset and they should like coming to work, sit in comfy chairs, and be in an environment to do their best work. Because the work is important!"lxix explained Harrison. Observers opined that Harrison's efforts to provide an enabling environment for the staff was one of the reasons for the organization figuring in Inc.'s2 2018 Best Workplaces and for around 1,000 people applying for a receptionist's position in the organization.lxx

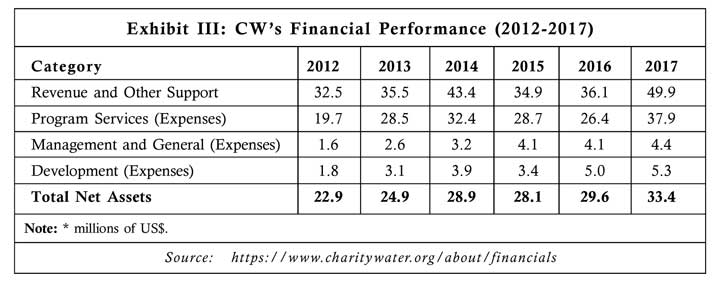

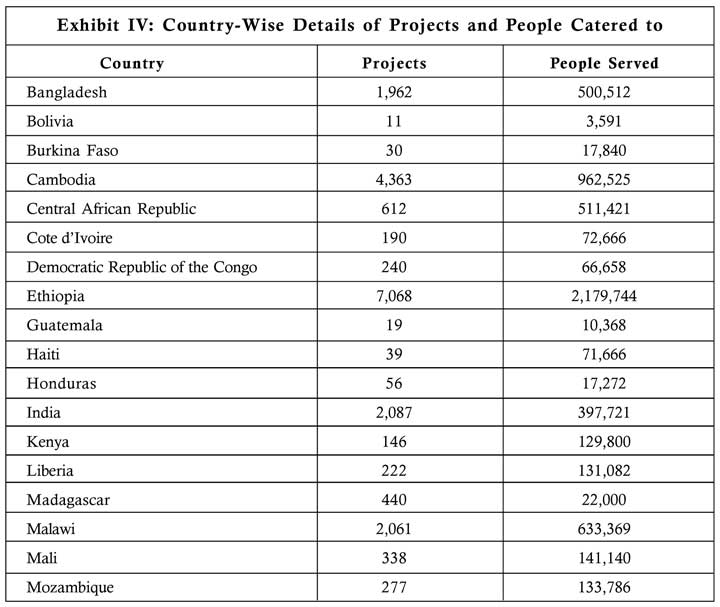

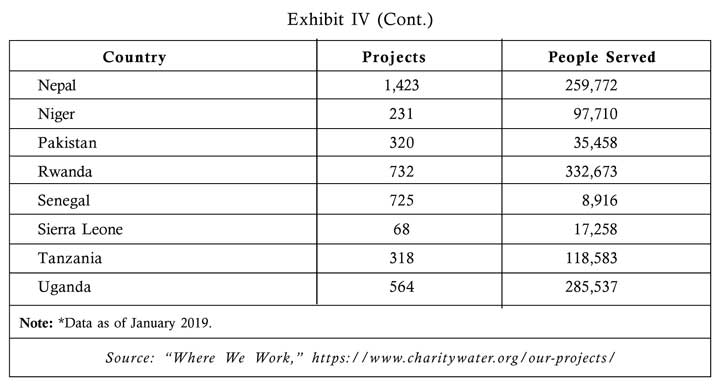

Impact By March 2018, CW employed 1,250 workers in the countries where it was working on water projects.lxxi By August 2018, it had raised US$320 mn-the number comprised the money raised for water projects as well as for operations. By January 2019, it had funded 29,725 water projects. As a result, 8,497,062 individuals in 26 countries got access to clean water (Refer Exhibit IV for details of country-wise projects and the number of people catered to).lxxii

Experts, however, noted that the impact of CW's work extended beyond mere access to clean water. They pointed to research by the World Health Organization which said that each dollar spent on clean water and sanitation initiatives returned US$4.3 due to people becoming healthier and being able to spend more time to benefit their communities and a decrease in healthcare expenses for individuals as well as for society.lxxiii, lxxiv According to observers, CW's initiatives, besides resulting in improved health and sanitation of the beneficiaries, gave them the time and financial wherewithal to build businesses, increase agricultural output, and feed their children.lxxv Several observers noted that girls, who had previously missed out on school earlier as they had to help their mothers in bringing jerricans of dirty water home, were attending school because of the safe and clean water provided by the organization's projects. "..girls..now worry most about access to books and other learning materials,"lxxvi commented an observer who had visited one of the villages where CW had executed a water project.

Chinks in CW's Armor?

According to observers, CW faced the risk of other charities emulating its strategy of engaging donors online. Doug Spencer (Spencer), director of resource development at Water for People, CW's partner in Rwanda, opined, "..I think Scott's program will have a shelf life. It will become tiresome and younger people will start to get skeptical because they are being bombarded online. It's not only Scott. His space is becoming much more competitive."lxxvii A donor, who concurred with Spencer, remarked, "It's true. If everyone gets that savvy at communicating their messages it will be harder for donors to decide."lxxviii Also, an expert doubted whether the organization would realize its goal of bringing clean drinking water to every person lacking access to it. He explained, "..it's important to recognize that charity can't possibly solve the global water crisis. "For about $30 a person, we know how to help millions," says charity: water. At that rate, providing clean safe water to 750 million people will cost $22.5 bn."lxxix So, was CW aiming too high and did it face the risk of eventually running out of steam?

End Notes

Amy Neumann, "Social Good Stars - Charity: Water's Scott Harrison," www.huffingtonpost.com, July 11, 2012.

ii "More Time for Moms Around the World," https://www.charitywater.org/stories/more-time-for-moms-around-the-world/

iii https://my.charitywater.org/about/mission

iv Alexandra Wolfe, "Scott Harrison Turned from Nightclub Promoter to Philanthropist," www.wsj.com, September 14, 2018.

v Alexandra Wolfe, "Scott Harrison Turned from Nightclub Promoter to Philanthropist," www.wsj.com, September 14, 2018.

vi David Karas, "Scott Harrison Found Meaning in Life by Starting Charity: Water," www.wsj.com, September 14, 2018.

vii Scott Harrison, "Thirst: A Story of Redemption, Compassion, and a Mission to Bring Clean Water to the World (Currency, 2018)".

viii Ibid.

ix Catherine Clifford, "How Charity: Water's Founder went from Hard-Partying NYC Club Promoter to Helping 8 Million People Around the World," www.cnbc.com, March 22, 2018.

x David Baker, "Charity Startup: Scott Harrison's Mission to Solve Africa's Water Problem," www.wired.co.uk, January 4, 2013.

xi Max Chafkin, "A Save-the-World Field Trip for Millionaire Tech Moguls," www.nytimes.com, August 8, 2013.

xii Alexandra Wolfe, "Scott Harrison Turned from Nightclub Promoter to Philanthropist," www.wsj.com, September 14, 2018.

xiii https://www.charitywater.org/our-approach/local-partners/

xiv John Rampton, "How a Nightclub Promoter Became the Leader of One of the Top Charities in the World," www.inc.com, February 25, 2015.

xv Alexandre Mars, "Doing Well by Doing Good: An Interview with Scott Harrison, Founder & CEO of Charity: Water," www.huffingtonpost.com, September 7, 2016.

xvi Jessica Floum, "Silicon Valley 'Well' Backs World Water Charity," www.sfgate.com, September 15, 2013.

xvii https://www.charitywater.org/global-water-crisis

xviii Scott Harrison, "Thirst: A Story of Redemption, Compassion, and a Mission to Bring Clean Water to the World (Currency, 2018)".

xix https://www.charitywater.org/global-water-crisis

xx "Solutions," https://www.charitywater.org/our-approach/solutions/

xxi "Our Approach," https://www.charitywater.org/our-approach/

xxii Ibid.

xxiii Catherine Clifford, "How Charity: Water's Founder went from Hard-Partying NYC Club Promoter to Helping 8 Million People Around the World," www.cnbc.com, March 22, 2018.

xxiv Amy Neumann, "Social Good Stars - Charity:Water's Scott Harrison," www.huffingtonpost.com, July 11, 2012.

xxv Steven Bertoni, "How Charity: Water Won Over the Tech World," www.forbes.com, December 19, 2013.

xxvi Gina Pace, "Creating Marketing Campaigns that Matter," www.inc.com, May 16, 2011.

xxvii "The 100% Model," https://www.charitywater.org/our-approach/100-percent-model/

xxviii Catherine Clifford, "How Charity: Water's Founder went from Hard-Partying NYC Club Promoter to Helping 8 Million People Around the World," www.cnbc.com, March 22, 2018.

xxix David Baker, "Charity Startup: Scott Harrison's Mission to Solve Africa's Water Problem," www.wired.co.uk, January 4, 2013.

xxx Steven Bertoni, "How Charity: Water Won Over the Tech World," www.forbes.com, December 19, 2013.

xxxi David Baker, "Charity Startup: Scott Harrison's Mission to Solve Africa's Water Problem," www.wired.co.uk, January 4, 2013.

xxxii Drew Neisser, "Who the Heck are the Bayaka and 7 Other Questions for Aspiring Leaders," www.fastcompany.com, August 16, 2010.

xxxiii Ibid.

xxxiv "5x5x5: Scott Harrison, Founder Of Charity: Water, On Crowdfunding, Technology For Social Good And Blessings In Disguise," www.huffingtonpost.com, November 15, 2012.

xxxv Nicholas Kristof, "Clean, Sexy Water," www.nytimes.com, July 11, 2009.

xxxvi Joseph Volpe, "The 21st-Century Charity That Puts Google and VR to Good Use," www.engadget.com, March 3, 2016.

xxxvii Ibid.

xxxviii Marty Swant, "How Virtual Reality is Inspiring Donors to Dig Deep for Charitable Causes," www.adweek.com, May 31, 2016.

xxxix Alexandre Mars, "Doing Well by Doing Good: An Interview with Scott Harrison, Founder & CEO of Charity: Water," www.huffingtonpost.com, September 7, 2016.

xl Ibid.

xli Marty Swant, "How Virtual Reality is Inspiring Donors to Dig Deep for Charitable Causes," www.adweek.com, May 31, 2016.

xlii Ben Paynter, "How Charity: Water Uses Data to Connect Donors and the People They're Helping," www.fastcompany.com, March 20, 2017.

xliii Ibid.

xliv Max Chafkin, "A Save-the-World Field Trip for Millionaire Tech Moguls," www.fastcompany.com, March 20, 2017.

xlv Gregory Ferenstein, "Trickle-Forward Economics: Scott Harrison's Water-Based Experiment in Viral Philanthropy," www.fastcompany.com, October 25, 2011.

xlvi Ibid.

xlvii Charles Duhigg, "Why Don't You Donate for Syrian Refugees? Blame Bad Marketing," www.nytimes.com, June 14, 2017.

xlviii Jason Haber, The Business of Good, (Entrepreneur Press, 2016).

xlix Paull Young, "My 5 Biggest Lessons from 5 Years Leading Digital at Charity: Water," https://medium.com, December 31, 2014.

l Max Chafkin, "A Save-the-World Field Trip for Millionaire Tech Moguls," www.nytimes.com, August 8, 2013.

li Stephanie Wolcott, "Make It Personal," https://ssir.org, December 5, 2011.

lii Elise Hu, "How Millennials are Reshaping Charity and Online Giving," www.npr.org, October 13, 2014.

liii Paull Young, "My 5 Biggest Lessons from 5 Years Leading Digital at Charity: Water," https://medium.com, December 31, 2014.

liv Cody Switzer, "Unconventional Charity: Water Aims to Raise $2 Billion for Clean Water," www.csmonitor.com, April 5, 2012.

lv Joseph Volpe, "The 21st-Century Charity That Puts Google and VR to Good Use," www.engadget.com, March 3, 2016.

lvi Ben Paynter, "How Charity: Water Uses Data to Connect Donors and the People They're Helping," www.fastcompany.com, March 20, 2017.

lvii Joseph Volpe, "The 21st-Century Charity that Puts Google and VR to Good Use," www.engadget.com, March 3, 2016.

lviii Ibid.

lix "Advancing Transparency and Sustainability," https://medium.com, November 22, 2016.

lx Ben Schiller, "These Sensors Raise the Bar of Accountability for Water Charities," www.fastcompany.com, January 11, 2016.

lxi "Advancing Transparency and Sustainability," https://medium.com, November 22, 2016.

lxii Ibid.

lxiii Ben Schiller, "These Sensors Raise the Bar of Accountability for Water Charities," www.fastcompany.com, January 11, 2016.

lxiv "Advancing Transparency and Sustainability," https://medium.com, November 22, 2016.

lxv Afdhel Aziz, "The Power of Purpose: How Charity: Water is Reinventing Philanthropy with Data and Compassion," www.forbes.com, December 19, 2018.

lxvi Scott Harrison, "Thirst: A Story of Redemption, Compassion, and a Mission to Bring Clean Water to the World (Currency, 2018)".

lxvii Joseph Volpe, "The 21st-Century Charity That Puts Google and VR to Good Use," www.engadget.com, March 3, 2016.

lxviii Brady Josephson, "5 Lessons Learned Over 10 Years with Scott Harrison from Charity: Water," www.huffingtonpost.com, October 24, 2016.

lxix Ibid.

lxx Brit Morse, "Why 1,000 People Applied to Be a Receptionist at This Nonprofit," www.inc.com, May 23, 2018.

lxxi Catherine Clifford, "How Charity: Water's Founder went from Hard-Partying NYC Club Promoter to Helping 8 Million People Around the World," www.cnbc.com, March 22, 2018.

lxxii https://www.charitywater.org/projects#

lxxiii https://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/monitoring/economics/en/

lxxiv Ben Paynter, "How Charity: Water Uses Data to Connect Donors and the People They're Helping," www.fastcompany.com, March 20, 2017.

lxxv David Baker, "Charity Startup: Scott Harrison's Mission to Solve Africa's Water Problem," www.wired.co.uk, January 4, 2013.

lxxvi Andy McLoughlin, "Why Wealthy Tech Entrepreneurs are Pouring Their Money into Water," www.theguardian.com, May 29, 2013.

lxxvii David Baker, "Charity Startup: Scott Harrison's Mission to Solve Africa's Water Problem," www.wired.co.uk, January 4, 2013.

lxxviii Ibid.

lxxix Marc Gunther, "Water Charities: A Glass Half Full," https://medium.com, April 26, 2015.