Jan'23

The IUP Journal of Organizational Behavior

Archives

Psychological Contract Breach and Job Outcomes: Moderating Role of Educational Qualification

Paresh Lingadkar

Assistant Professor, Goa Business School, Goa University, Goa, India; and is the corresponding author.

E-mail: paresh.lingadkar@unigoa.ac.in

K G S Narayanan

Professor, Goa Business School, Goa University, Goa, India. E-mail: kgsmenon@unigoa.ac.in

The study examines the moderating role of educational qualifications in Psychological Contract Breach (PCB) and job outcomes. Using One-way ANOVA, the study examines the effect of different levels of educational qualifications on the type of PCB and employee outcomes. The results indicate that there is a significant effect of educational qualifications on the type of PCB and all employee outcomes, except turnover intention. The study also examines the moderating effect of educational qualifications on the relationship between PCB and job outcomes. The results show that educational qualifications moderate the relationship between PCB and turnover intention. Visual inspection of the interaction plot shows that as the educational level increases, the effect of PCB on turnover intentions also increases.

Introduction

Psychological Contracts (PC) consist of the beliefs employees hold about the provisions of the mutual agreement between themselves and their organizations (Rousseau, 1989; and Robinson and Rousseau, 1994). PC is defined as the employees' beliefs regarding mutual obligations between the employee and the organization (Rousseau, 1998; and Conway and Briner, 2009). PC has three aspects: perceived employee obligations, perceived employer obligations, and perceived fulfilment or violation of obligations. Weick et al. (1983) argued that when two parties can predict what each other will do in an interface (based upon both inference and examination of past practices), a contract to continue this behavior into the future emerges and structures their future relationship. Thus, expectations shaped during exchanges regarding the future pattern of reciprocity constitutes a PC. To be specific, PC consists of the commitments that employees consider their employer owes them and the obligations the employees consider they owe to their employer in return. These commitments/obligations/expectations cover the whole arrangement between workers and organizations (Anwer et al., 2020). The most accepted operational definition of the PC is the one provided by Rousseau (1995): "The psychological contract is individual beliefs, shaped by the organization, regarding terms of an exchange agreement between individuals and their organization" (Botha and Steyn, 2021).

Literature Review and Hypotheses Formulation

The evolution of the concept of PC goes back to 1938 from the works of Barnard's Theory of Equilibrium. According to this theory, the two parties involved emphasize on the balance in their relationship. Blau (1964) propounded that social contact has value to people and he explored the forms and sources of this value in order to understand joint outcomes. The theory further stated that contrary to economic exchange, social exchanges tend to be long-term.

Transactional PC is considered to be based on a very precise exchange that exists over a limited period. These contracts try to emphasize the financial advantage one will get from the employer. Transactional PC is relevant to specific terms and conditions. Employees prefer to seek employment somewhere else when the employer fails to fulfil their expectations. Transactional PC shifts the risk associated with the economic uncertainties from employer to employee. Workers will contribute to the organization in line with the contributions they receive from the organization. Transactional PC is less functional when they are a byproduct of a relationship. This means they are not recognized and managed properly.

In such cases, the workers either leave the organization or indulge in anti-organizational behavior. Transactional PC remains unchanged and focuses on short-term relationships in which the result is more essential rather than the continuation of the relation (Tsui, 1997). According to Rousseau (1995), Transactional PC has less personal involvement and low emotional investment. It is mainly limited to the exchange of economic resources (Aselage, 2003). Smithson and Lewis (2000) concluded that younger employees focus more on short-term monetary-nonmonetary arrangements rather than having a long-term relationship as compared to older employees.

The other type of PC is called Relational PC. It includes terms such as loyalty, commitment, stability, etc. Employees with Relational PCs are more willing to work overtime, whether paid or not. They are ready to help their colleagues on the job and ready to support organizational changes that are beneficial. They get upset, especially when the reciprocal arrangements from the side of the organization do not come. This even leads to frustration, job dissatisfaction, and further erosion of employment relationships. In Relational PC, the relationship between employee and employer is more important than anything else, which are based on collective interest of both (Parks and Kidder, 1994) and are linked to the societal exchange (Millward and Brewerton, 1999; and 2000) concerning socio-emotional assets (Aselage, 2003), presenting the conventional employment relationship in which both acknowledge each other's interest (Brewerton, 2000).

Psychological Contract Breach (PCB) takes place when the worker perceives that their employer has been unsuccessful in fulfilling the obligations involving the PC (Robinson, 1996; and Morrison and Robinson, 1997). Several papers have discussed the varying nature of the PC breach and the general decrease in mutual loyalty amongst employees and their organizations (e.g., Moss, 1998; and Parks et al., 1998). These papers have typically provided subjective evidence of the types of PC breach that employees have experienced. Another area of research has focused on the negative effects of PC breach (or violation) on employee attitude and behavior (e.g., Robinson, 1996; Morrison and Robinson, 1997; Robinson and Rousseau, 1994; and Turnley and Feldman, 1999). The literature suggests that PC breach results in a wide range of negative outcomes, including low job satisfaction, reduced trust in the organization, and increased distrust about organizational life in general and higher intention to quit. However, PC fulfilment has a positive effect on employee performance (Sunarta et al., 2022). A study by Baral and Bhargava (2010) concluded that characteristics, supervisor support, and work-family culture have a strong relationship with job satisfaction, and all are positively related to job satisfaction and vice versa; the higher the level of PC breach, the higher the job dissatisfaction (Rigotti, 2009). Not only PC breach and job satisfaction are significantly related, but it was concluded that for employees to be satisfied, a higher level of support must always originate from the organization, through honoring all agreed terms stated in the conditions of employing them (Bahadir et al., 2022) as this will be a great motivator in ensuring productivity and efficient sustainability. When employees perceive that there is a breach of PC, they also perceive that their organization does not support them (Ballou, 2013), forcing them to leave the organization (Joshy and Srilatha, 2011; Paille and Dufour, 2013; Hartmann and Rutherford, 2015; and Algamdey, 2021). Additionally, PC breach predicts emotional exhaustion (Gakovik and Tetrick, 2003), discomfort and dissatisfaction with their current job, despite job security (Joshy and Srilatha, 2011); job dissatisfaction leads to negative employee behavior (Turnley and Feldman, 2000).

Education is an integral part of one's total human capital endowment. Research studies on educated employees have often concentrated on the number of employees who are moving from one organization to another. There are a number of studies showing that PC breach results in deviant behavior, which is detrimental for the organization. There exist mixed findings on educational level effects on job outcomes and PC (Aggarwal and Bhargava, 2013). The level of education is one crucial factor that influences the formation of PC (Guest, 2004).

Past studies argued that highly educated employees have the patience and ability to understand the situation better and to consider it positively because they possess persistence, rationality, and thinking power. Glenn and Weaver (1982) and Burris (1983) argued that higher level of education helps the individuals to secure a better job which provides them with autonomy, right employment conditions, prestige, promotion, the possibility of developing their professional capacities and increased sense of personal control. Employees with higher educational qualification are less vulnerable to stress because of their exceptional ability to master the tasks and manage the work (Aggarwal and Bhargava, 2013). Therefore, there is a strong expected relationship of educational levels and PC which affects the employment relationship. Hence, it is hypothesized that there is a significant difference between employees' educational qualification and their opinion concerning the type of PC breach and employee outcomes.

Generally, people with higher educational levels are found to be satisfied with their job. Hall (1994) believed that the higher the educational level, the more the expectations, which might result in dissatisfaction when not fulfilled. This view is also supported by Verhofstadt et al. (2007), Clark and Oswald (1995), Smulders (1999), and Coyle-Shapiro and Kessler (2000). Individuals with at least a college education have relatively higher expectations (Bellou, 2009). The level of education also affects the payment-related issues of the employees. For example, Koys et al. (1989) suggested that the level of employees' education affects their desire for performance-based pay. In particular, they found that highly educated employees prefer a performance-based pay system, and limited educated employees prefer a non-performance-based pay system. Highly trained employees also contribute more to the organization by working overtime, which is unpaid (Engellandt, 2003). According to Hammett (1984), the new generation of highly educated workers want more opportunities for development, autonomy, flexibility, and meaningful work experiences. The study by Francisco et al. (2016) found that educational level does not influence job satisfaction. However, it does have an inverse effect on organizational commitment; the lower the educational level of employees, the higher their commitment. Several other authors have shown that educational level has a negative effect on satisfaction in certain jobs (Clark and Oswald, 1996; Sloane and Williams, 1996; and Gazioglu and Tansel, 2006).

Further, as the educational level increases, the employee shift to Transactional PC from Relational PC, which suggests that educated employees view their employment relationship changed as the educational level increases (Luc-Sels et al., 2004); the level of job satisfaction increases with educational level (Theodossiou et al., 2005); and individuals who obtain high qualifications are more satisfied with their jobs (Lydon and Chevalier, 2002). Interestingly, there are limited studies on the effect of educational level on PC Breach in the Indian context and that too in the IT sector. Depending on employees' personal and professional inclination, education may raise one's expectations. The higher the educational level, the greater the chances that an employee will be dissatisfied with unappealing, routine tasks or those lacking in autonomy and power. After analyzing several studies on the subject, it is proved that there exists a positive relationship between the two variables, such that job satisfaction increases as educational level increases, and one can argue that the educational level of employees significantly influences the perception of PC breach.

With regard to organizational commitment and its relationship with employees' educational levels, several studies (Meyer et al., 2002; and Manriquez et al., 2010) have suggested that employees' commitment decreases as employees' educational level increases, while commitment increases with lower educational levels. The reason for this could be, as employees' educational level increases, their knowledge increases, and their freedom, independence, and confidence also increase, which leads them to seek alternative work in other organizations that satisfy their needs (Dello et al., 2013). Another study by Tura (2020), explored correlation between employee educational status and turnover and concluded that educational status is one of the significant contributors for employee turnover intention. To be more specific, scientific studies analyzing the relationship between employees' educational level and employee work outcomes (job satisfaction, organizational commitment, perceived organizational support and turnover intention) are neither conducted nor provide a clear conclusion that clearly defines the relationship flow. In short, it is even more significant to throw light on how the relationship between these variables develops and also to contribute to the theoretical knowledge. Therefore, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 1: Educational qualification moderates the relationship between PCB and employee outcomes.

Hypothesis 1a: Educational qualification moderates the relationship between PCB and job satisfaction.

Hypothesis 1b: Educational qualification moderates the relationship between PCB and Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB).

Hypothesis 1c: Educational qualification moderates the relationship between PCB and perceived organizational support.

Hypothesis 1d: Educational qualification moderates the relationship between PCB and turnover intention.

Data and Methodology

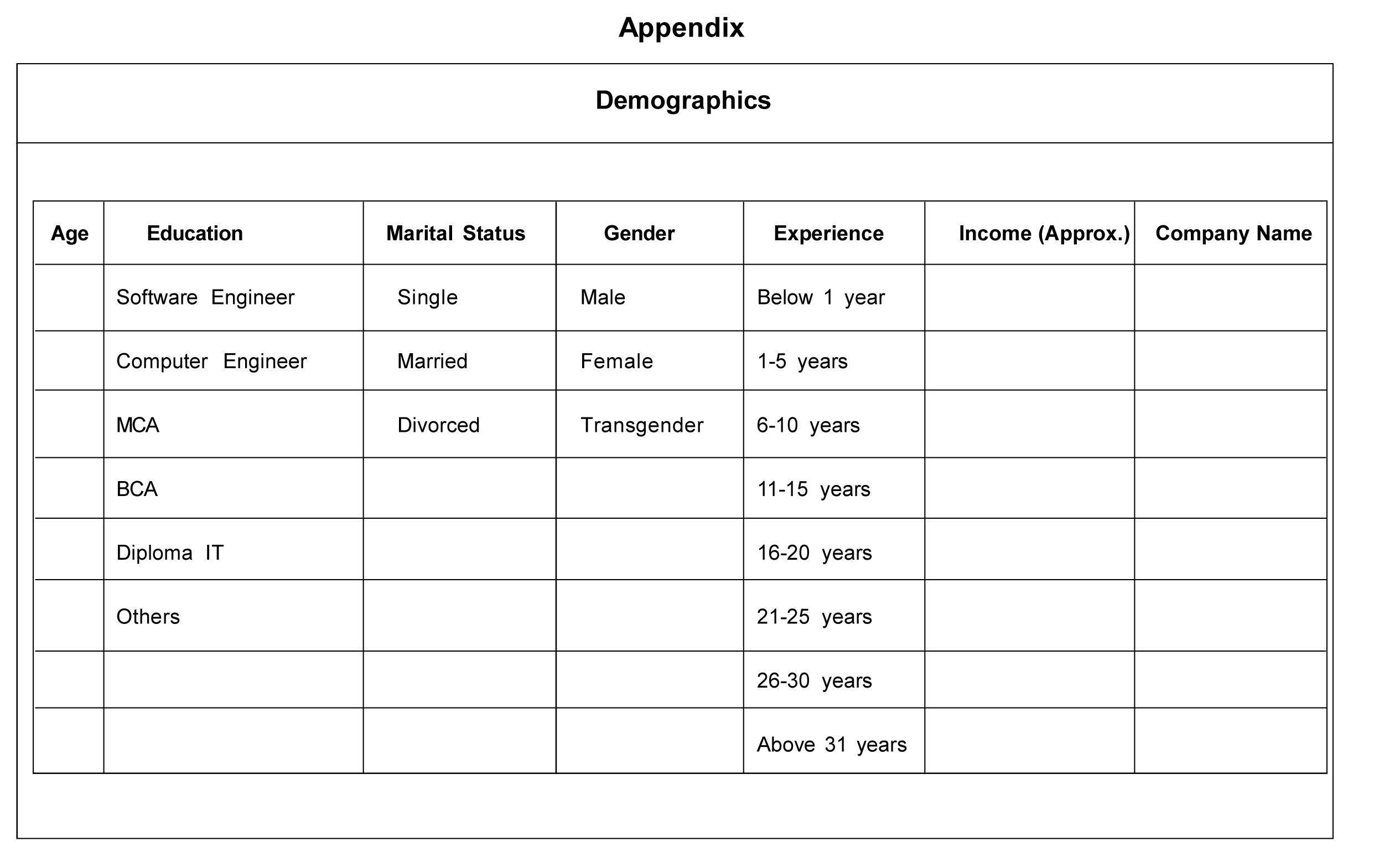

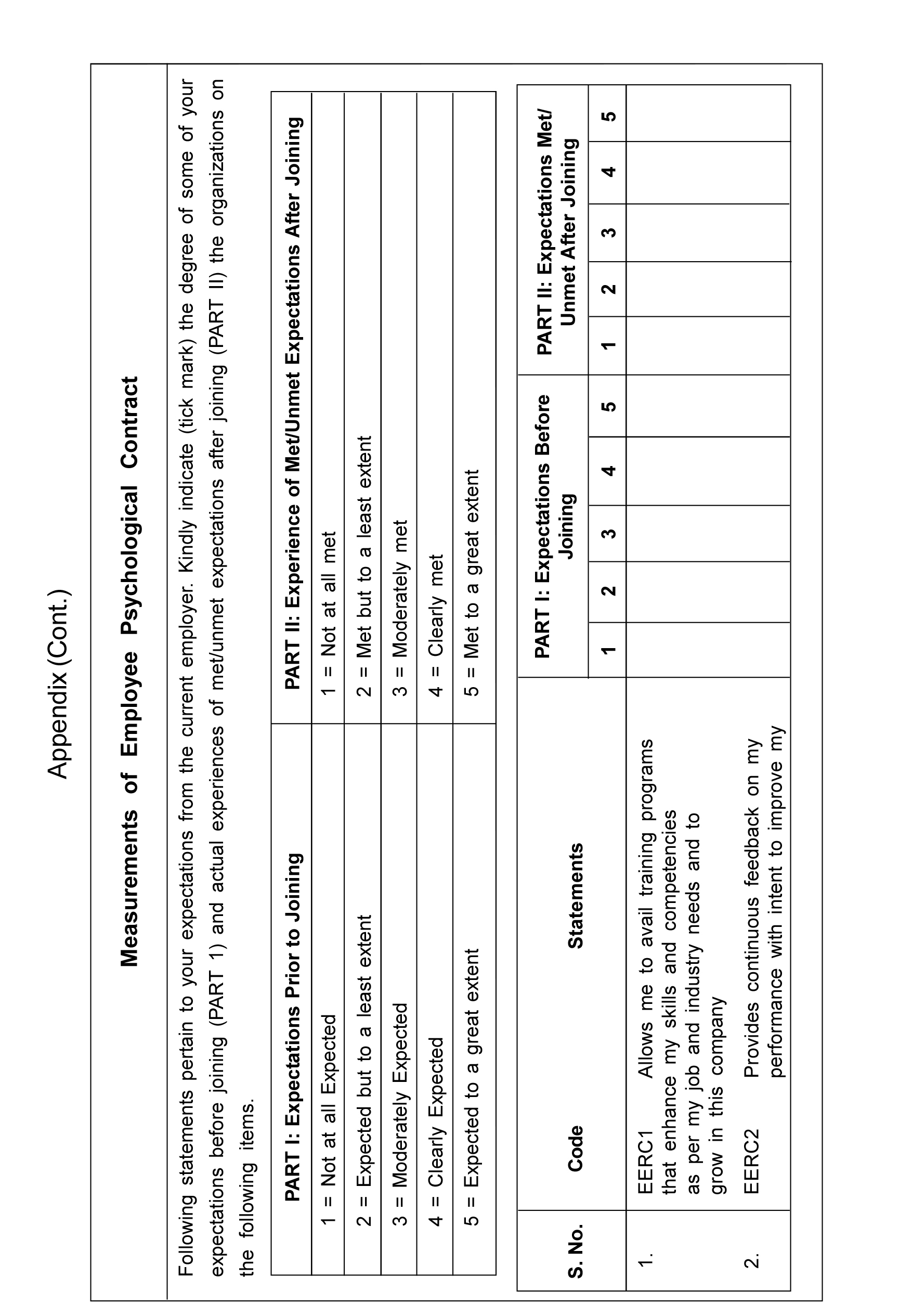

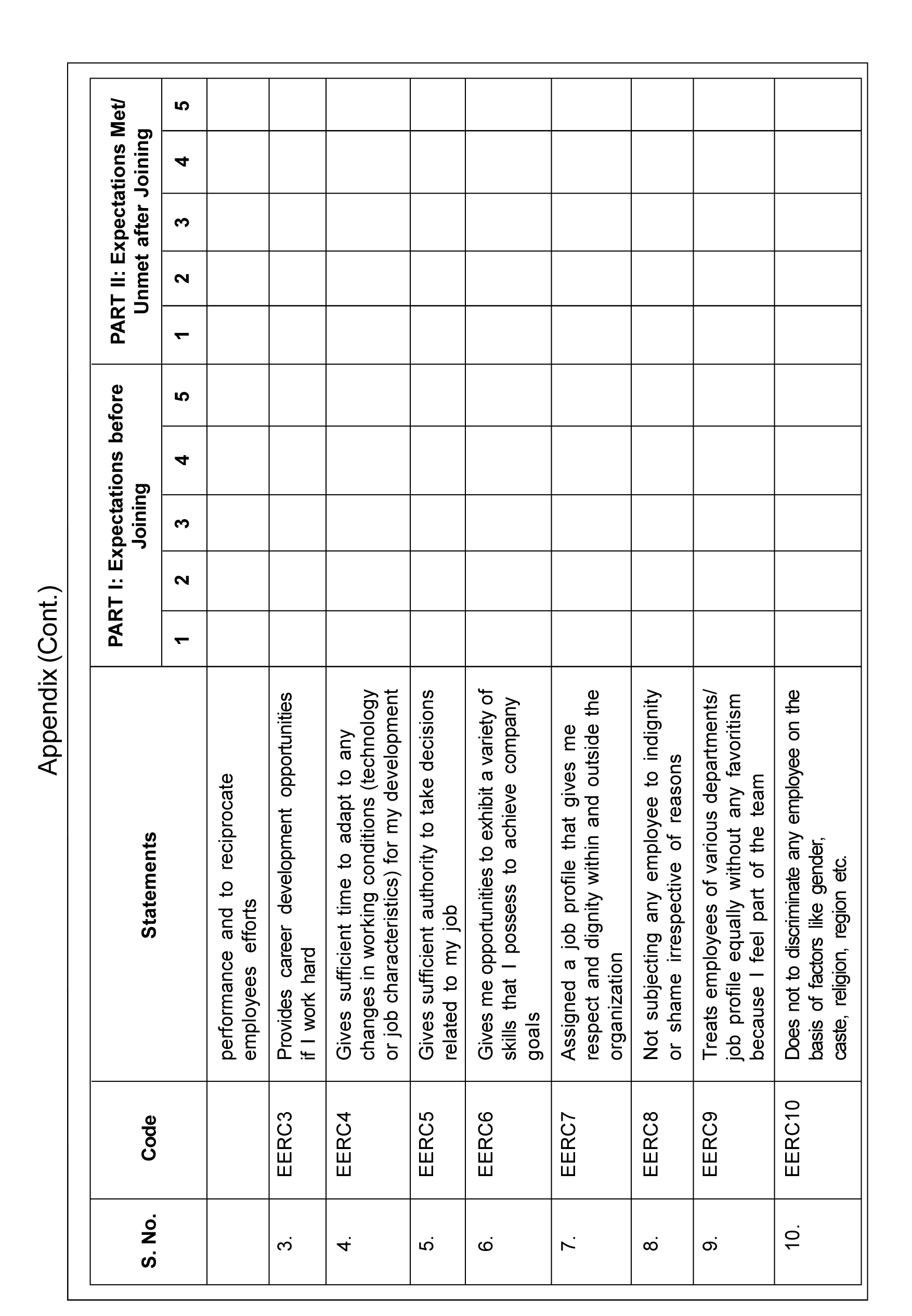

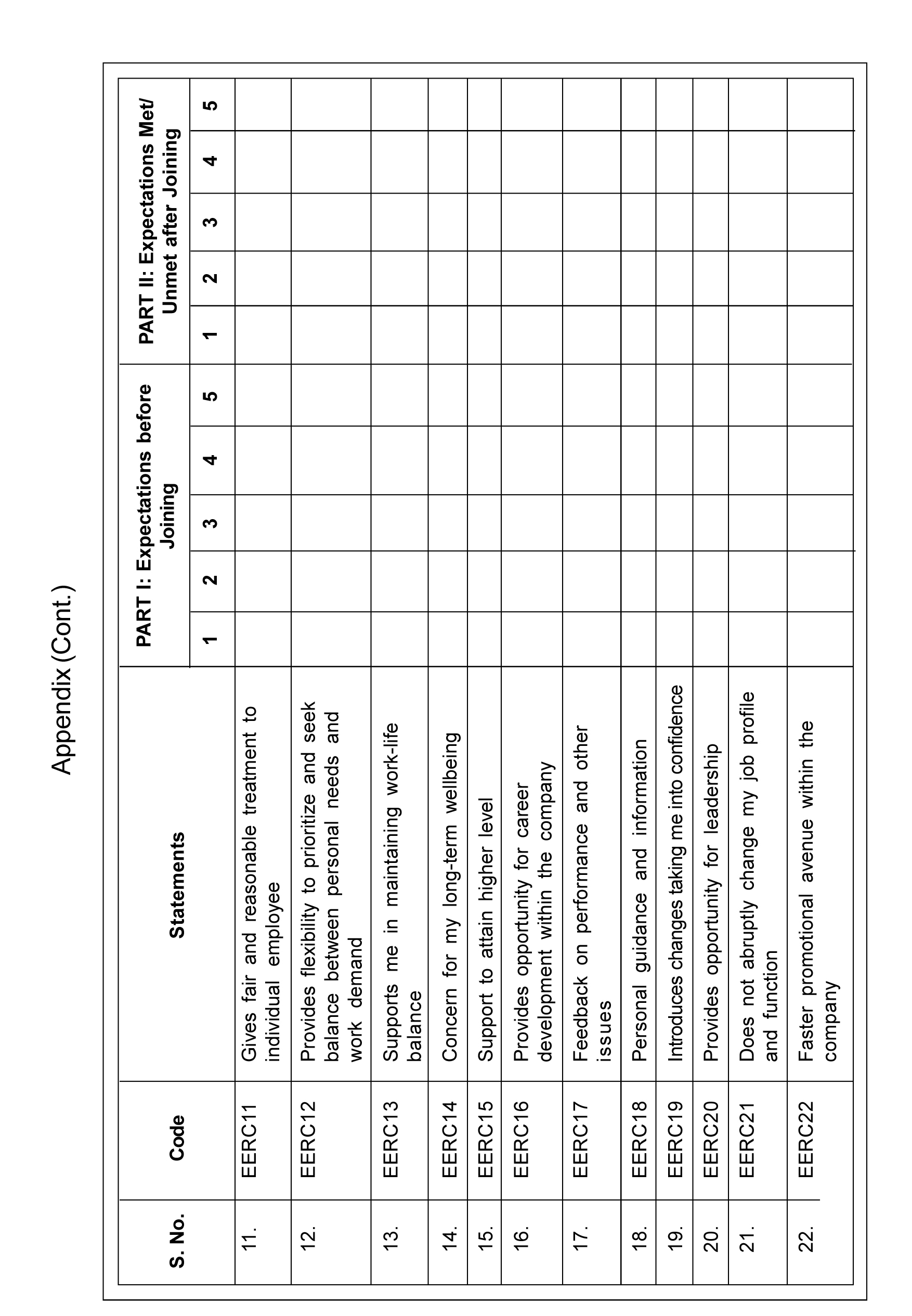

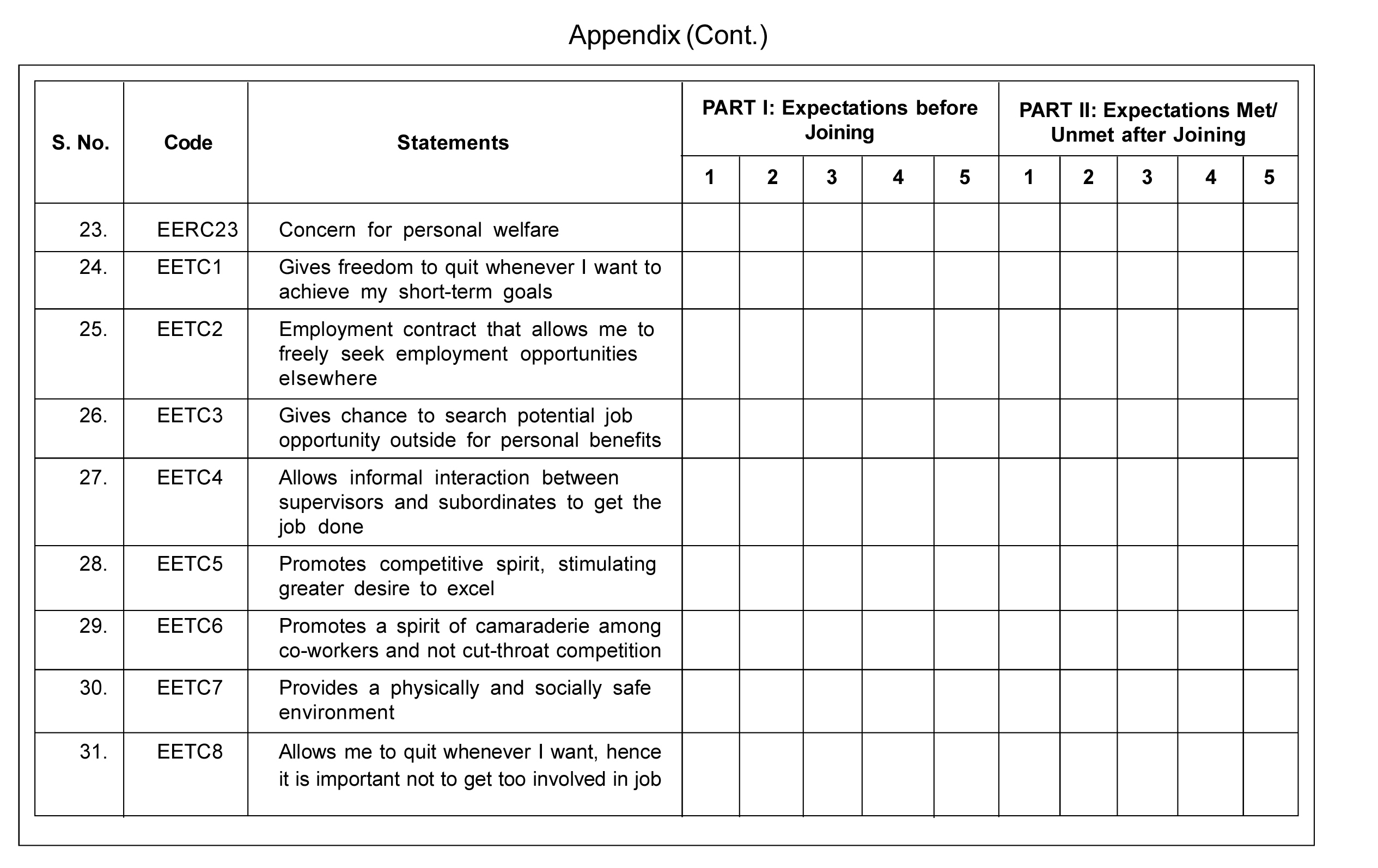

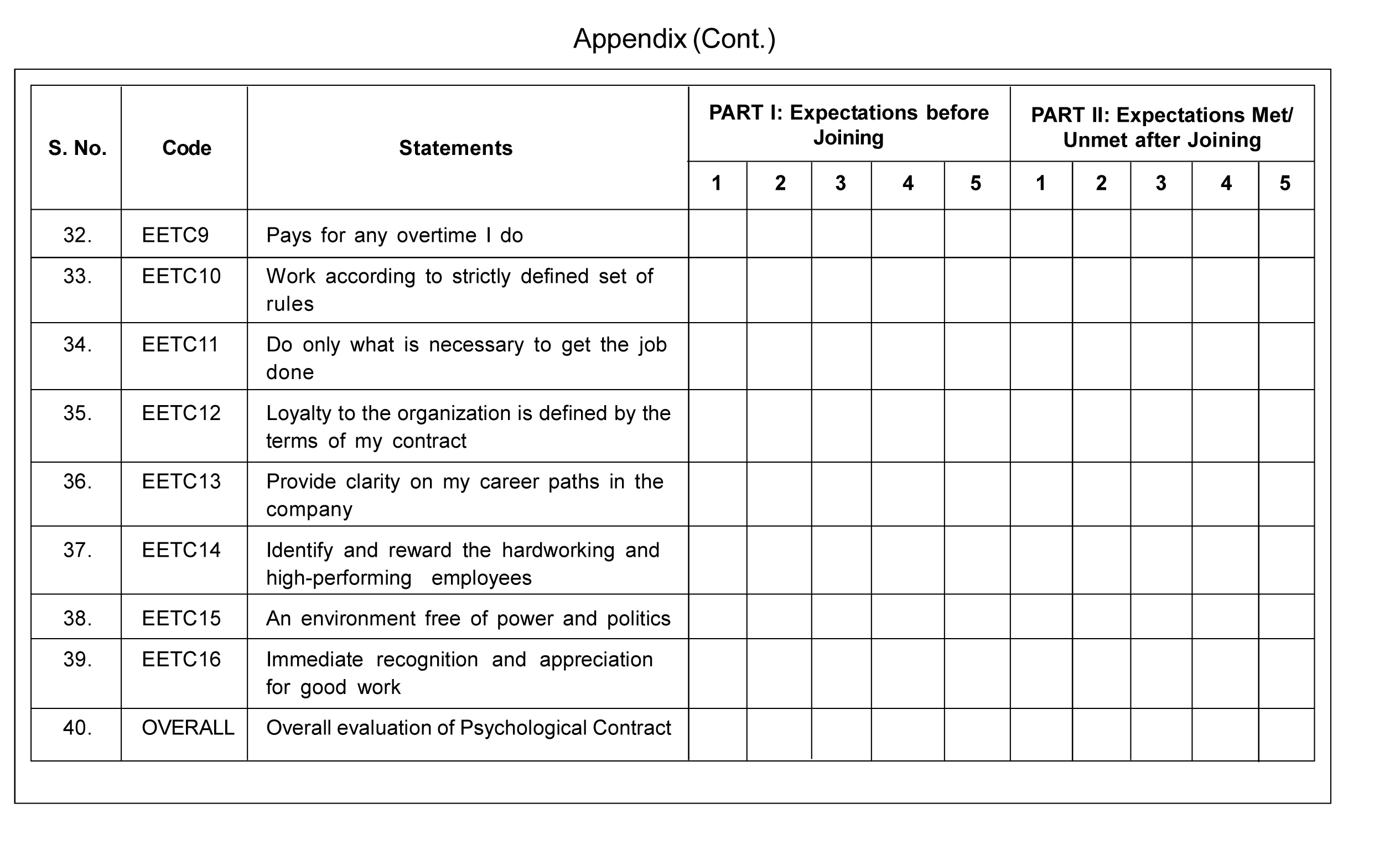

PC was measured by items adopted from PC questionnaire of Millward and Hopkins (1998) and Rousseau (1995). The researcher is expected to provide extensive information about the scale's reliability and validity. In the present study, the instrument to measure the Psychological Contract (see Appendix) has been adopted from Sankaranarayanan and Lingadkar (2020). The whole instrument was put through a content validity process to check the suitability in the Indian IT sector by using Item-wise Content Validity Index I-CVI by Beck (2006). The instrument used was a 5-point Likert Scale that ranged from 1 to 5 to rate expectations. All the items were reverse coded to represent PC breach rather than fulfilment (Bellou, 2009).

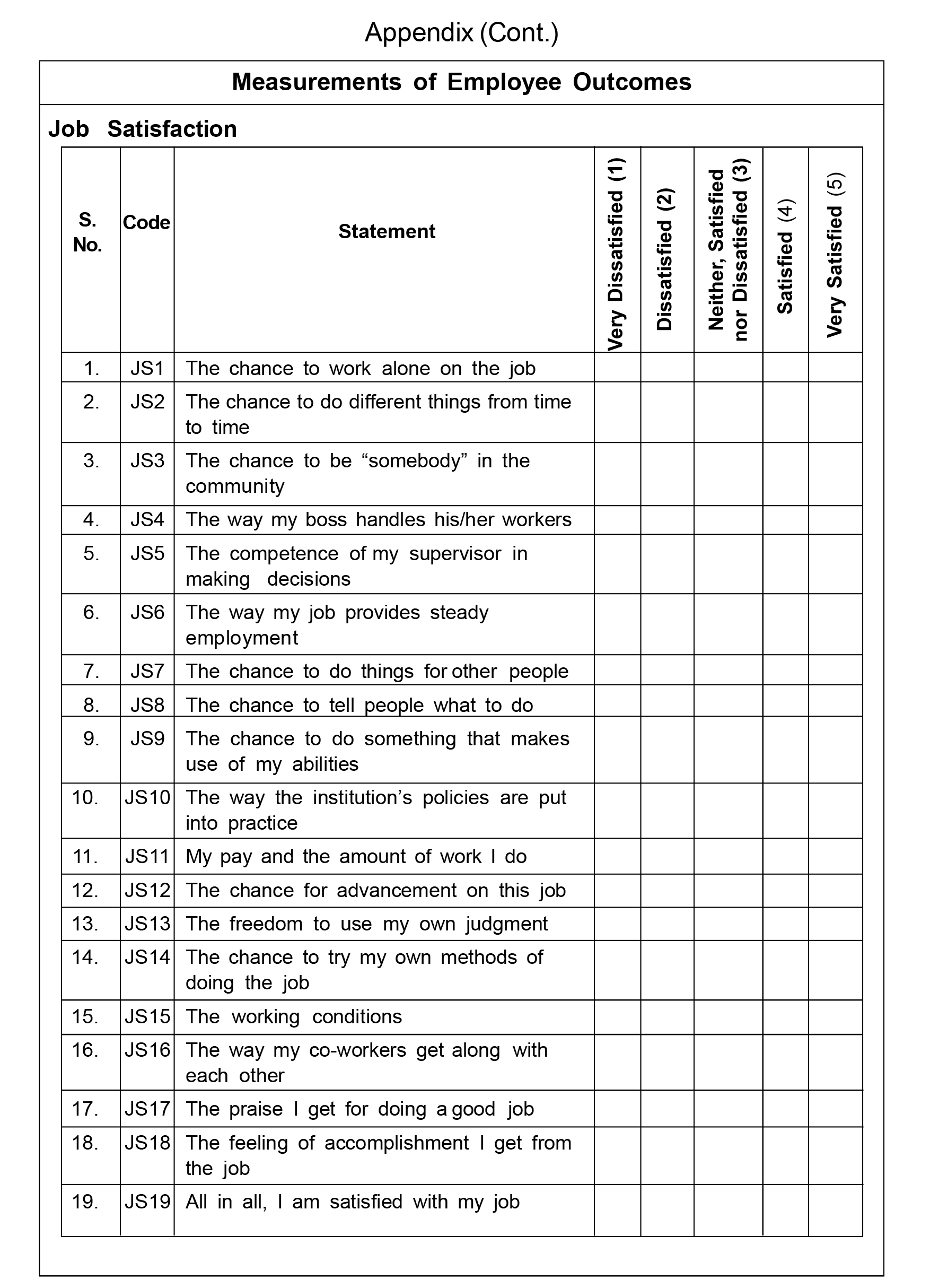

One outcome variable used is Job Satisfaction (JS). It is an attitudinal variable that reflects how people feel about their jobs. It emphasizes the specific task environment where an employee performs his/her duties and reflects the more immediate reactions to specific tangible aspects of the work environment (Mowday et al., 1982). A short version of the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire (Weiss et al., 1967) has been used to measure employee job satisfaction. The instrument comprises 19 statements and uses the 5-point Likert scale ranging from Very Dissatisfied = 1 to Very Satisfied = 5. The scale reliability is 0.959.

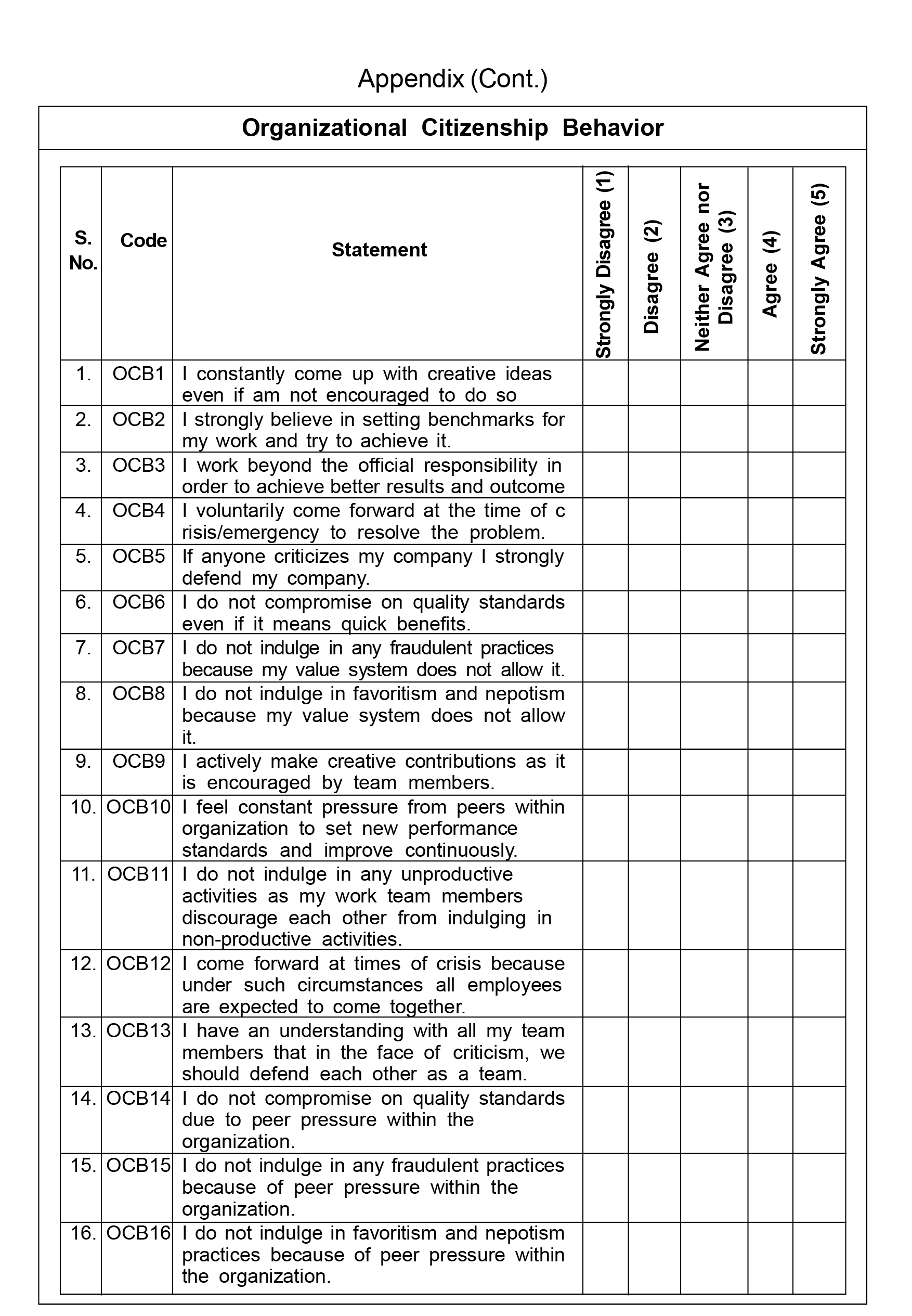

Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB) is discretionary individual behavior, not directly or explicitly recognized by the formal reward system, and that in the aggregate promotes the effective functioning of the organization (Organ, 1997). OCB is the behavior displayed by the employees beyond the prescribed boundaries of formal job roles, systems and procedures to benefit the organization. A 16-item OCB scale developed by Smith

et al. (1983) has been used to capture the OCB of the employees. A five-point Likert scale is used ranging from strongly disagree= 1 to strongly agree 5. The scale reliability is 0.928.

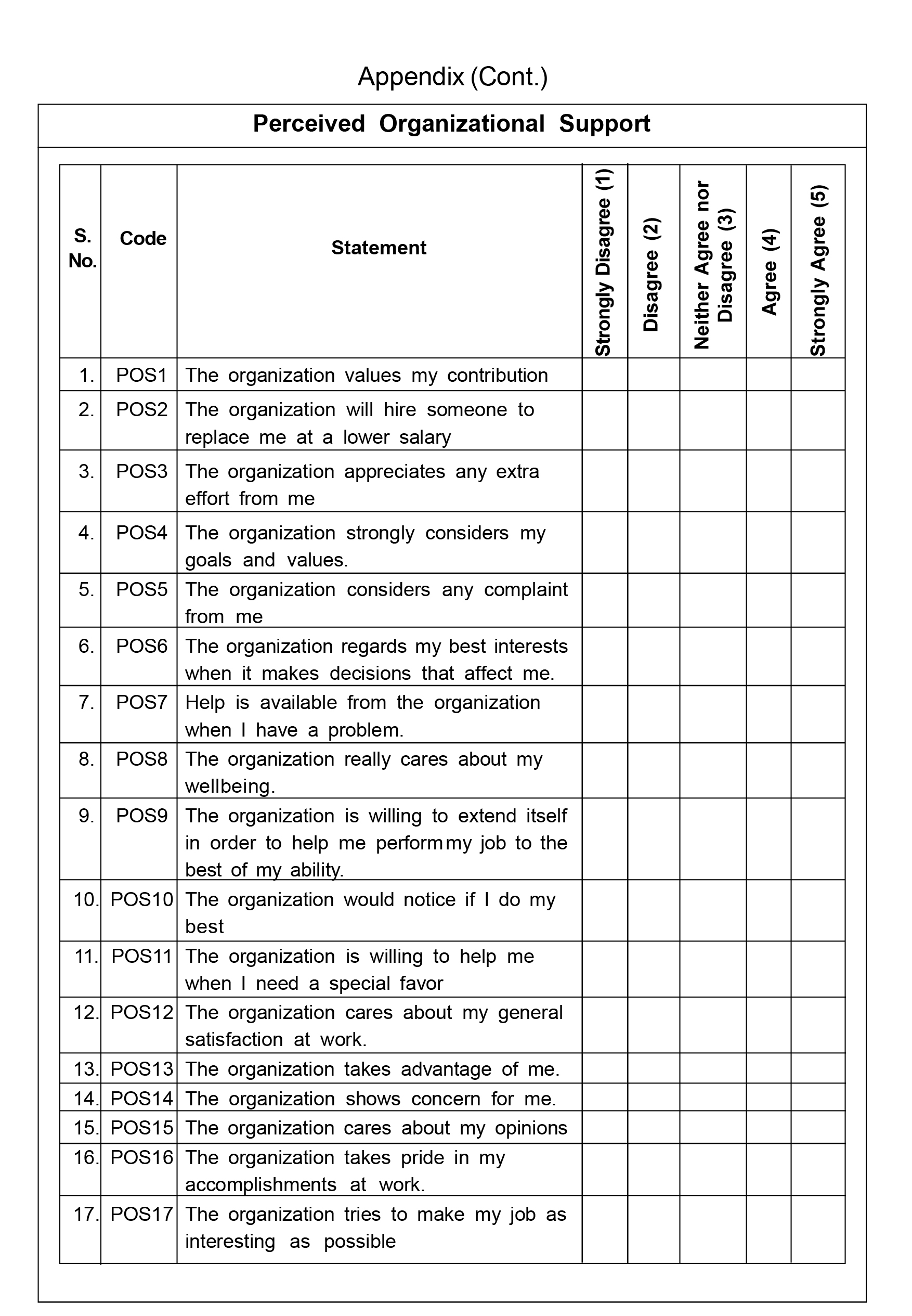

Perceived Organizational Support (POS) is defined as "the extent to which the organization values the contributions and cares about the wellbeing of its employees" (Eisenberger et al.,1986) and is measured using a 17-item short version scale taken from Eisenberger et al. (1986). Participants indicated the degree to which they agreed with each statement on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree = 1 to strongly agree = 5. The scale reliability is 0.863.

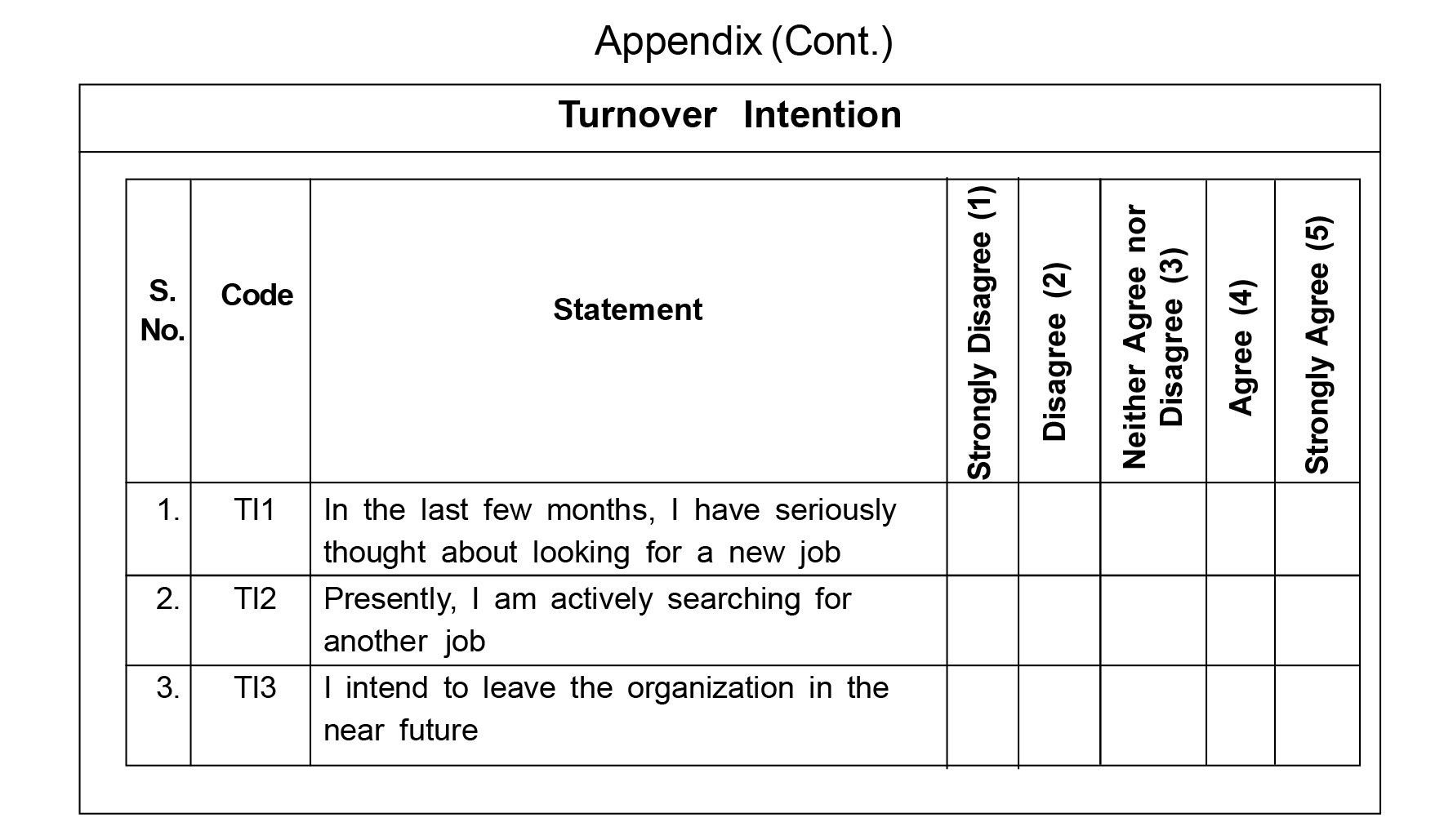

Turnover Intentions (TI) can be referred to as "conscious and deliberate willfulness of employees to leave the organization" (Meyer et al., 1993). It is the subjective probability that an employee will leave his organization within a certain period and measured on three items of Meyer et al. (1993). Participants indicated the degree to which they agreed with each statement on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree = 1 to strongly agree = 5. The scale reliability is 0.750.

Sampling Frame

The study includes employees with experience of one year or more from a company listed either on BSE or NSE with operations in the Indian market for one year or more. The respondents were identified through personal contacts, social sites, and human resource recruitment agencies and were contacted personally as well through their email contacts. The author was successful in collecting the responses from 406 respondents using convenience sampling method. The study was conducted from November 2020 to April 2021.

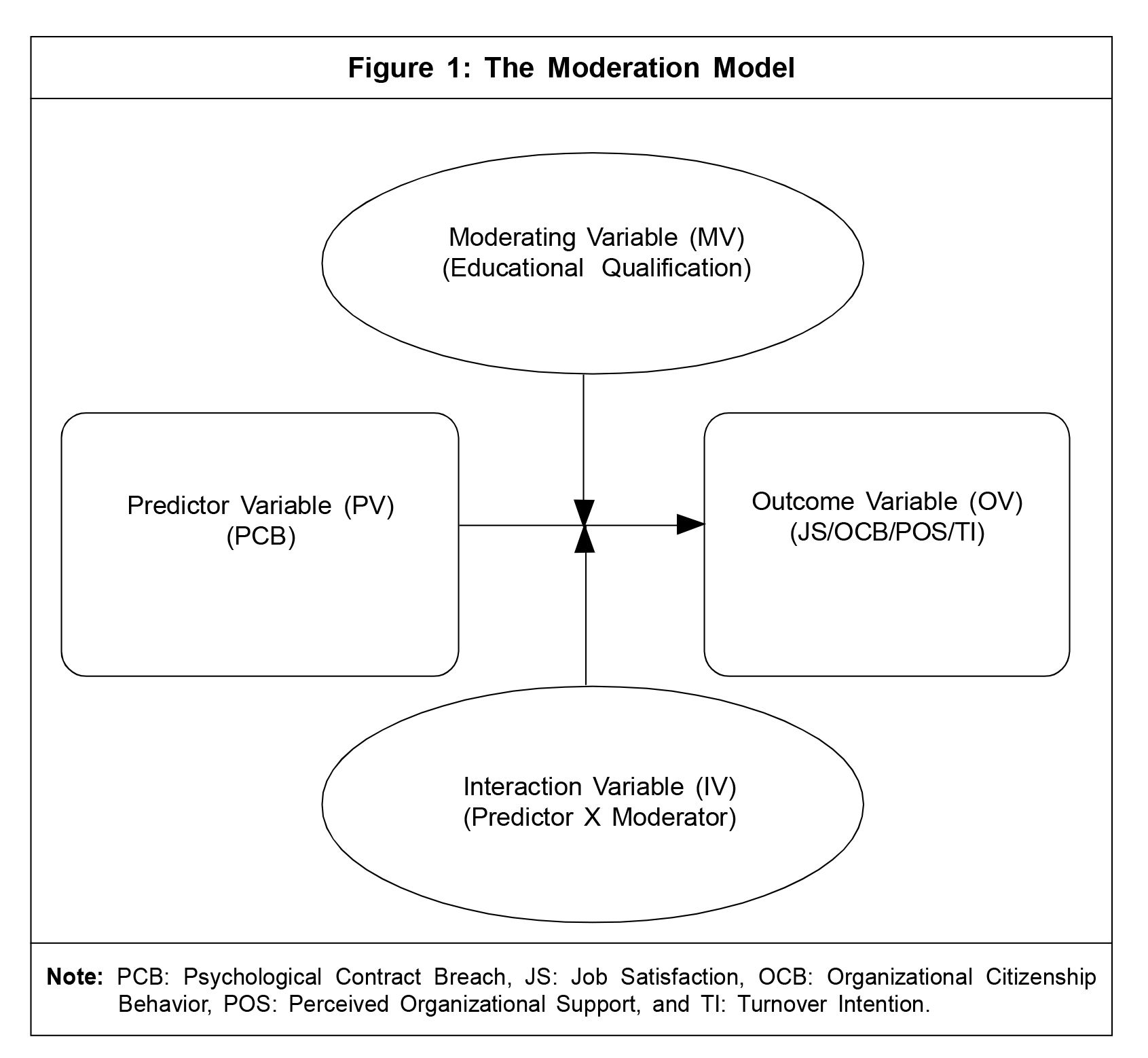

To examine the role of educational qualification in the relationship of PCB and job outcomes, inferential analysis, using t-test and one-way ANOVA, has been done. Hierarchical Multiple Regression analysis with Andrew Hayes Process has been undertaken to test the moderation/interaction effect. In testing moderation, the author particularly looked for the interaction effect between the Predictor variable and the Moderating variable and whether or not such effect is significant in predicting the outcome variable. The Moderation model is presented in Figure 1.

Moderation implies an interaction effect, where introducing a moderating variable changes the direction or magnitude of the relationship between two variables (Aiken, 1991). If the results of Regression analysis show significant moderating effect, then the output generated by the Andrew Hayes Process is used to generate an interaction plot that indicates the effect of the moderating variable.

Reason Behind Choosing IT Companies in India

IT industry is one of the fastest-growing industries in the world. The industry has produced unbelievable job opportunities for Indians and also migrants. The industry has adopted world-class standards and offers superior compensation and lots of training and development opportunities to its employees. There are many private associations like iSPIRIT and NASSCOM, which keep a close eye on the Indian IT industry. They publish several reports and lots of information every year.

Another rationale for researching PC is that the business organizations, specifically those from the IT industry, are under tremendous pressure to grow and sustain in the vibrant business environment, pressures of globalization, urbanization, cut-throat competition, and higher production targets, which has changed the face of HRM strategies in the organization, i.e. employment relationship goals (Budhwar et al., 2017; and Guest, 2017). The IT sector in India is considered as a key private sector for employment, especially for women. However, one has to also understand that the work is time-bound, exclusively tailor-made as per the requirements of the customer and technology-determined, which results in high job expectations and security of the job. In such types of circumstances, there is every prospect that the employees will build up stress and anxiety, which will additionally lead to a slowdown of job performance and sometimes leaving the job. Past studies highlighted that software professionals in India are at a bigger risk of burnout and the reason is unknown at large. Therefore, it is of utmost importance to address the problem of high attrition rate in the IT sector resulting in loss of precious resources and high cost to the employer.

Results

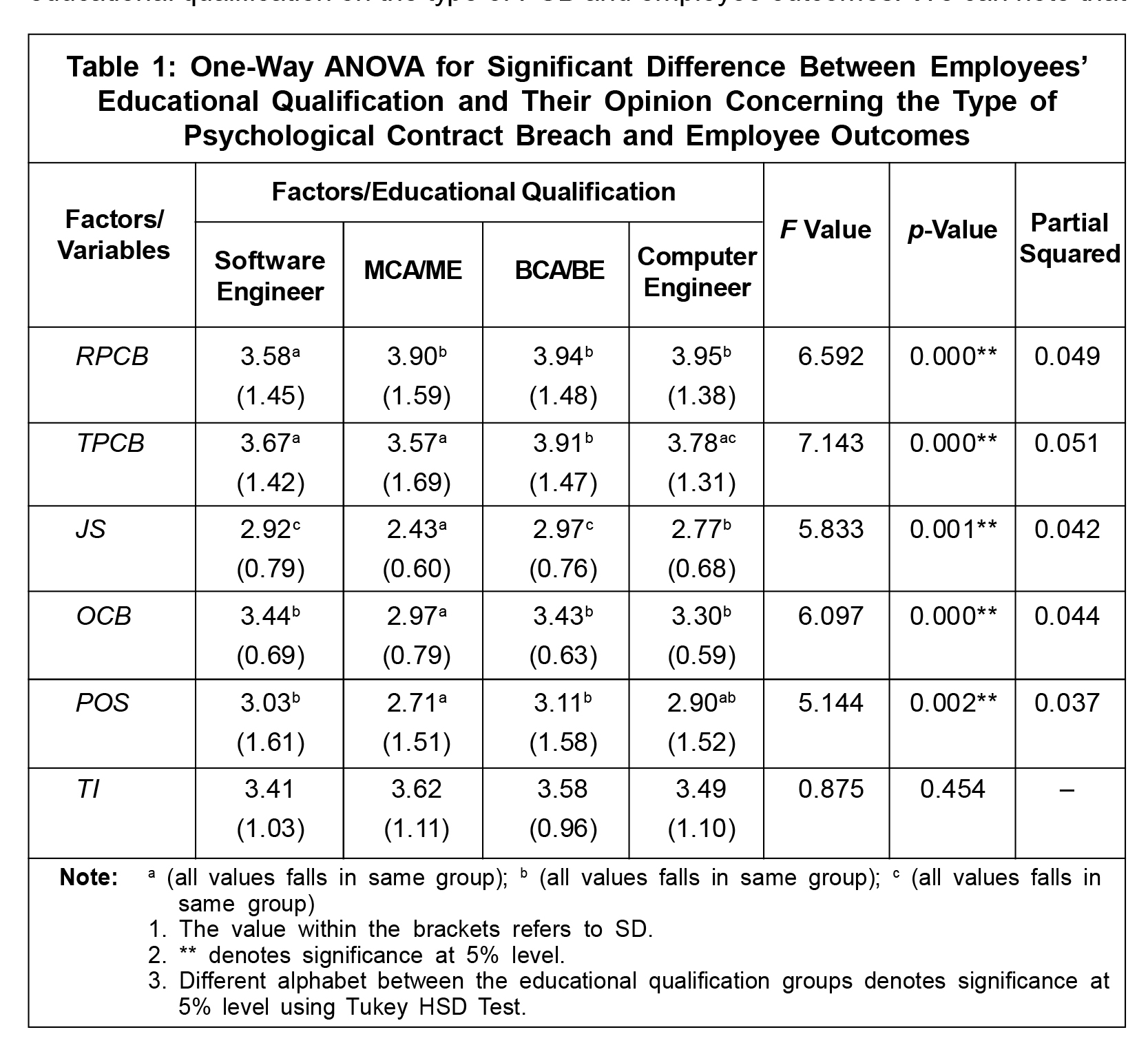

Table 1 presents the results of one-way ANOVA between the subjects on the effect of educational qualification on the type of PCB and employee outcomes. We can note that there is a significant effect of educational qualification on the type of PCB and employee outcomes, except Employee Turnover Intention (p = 0.454), at a 5% level of significance. Tukey post hoc test has been used to compare means as it is a suitable test for unequal sample size.

(3,402), P = 0.000. A post hoc comparison using the Tukey HSD test indicates that the mean score of software engineers (M = 3.58, SD = 1.45) is significantly different from all other educational qualification groups. Other educational qualification group includes MCA/ME (M = 3.90, SD = 1.59), BCA/BE (M = 3.94, SD = 1.48), and computer engineers (M = 3.95, SD = 1.38) are significantly not different. The different educational qualification accounts for 4.9% of the variance in the Relational PCB.

The table also points out the statistically significant effect of educational qualification on Transactional PCB, F = 7.143 (3,402), p = 0.000. A post hoc comparison using Tukey HSD test indicates that the mean score of software engineers (M = 3.67, SD = 1.42) and MCA/ME (M = 3.57, SD = 1.69), are significantly no different from each other. BCA/BE (M = 3.91, SD = 1.47) differs significantly from all other groups and Computer engineers (M = 3.78, SD = 1.31) interestingly similar in mean value to Software engineers and MCA/ME. The different educational qualification accounts for 5.1% of the variance in the Transactional PCB.

There is a statistically significant effect of educational qualification on employees job satisfaction, F = 5.833 (3,402), p = 0.001. A post hoc comparison using the Tukey HSD test indicates that the mean score of MCA/ME (M = 2.43, SD = 0.60) is significantly different from all other educational qualification groups. Educational qualification group, namely, computer engineers (M = 2.77, SD = 0.68), is also significantly different from all other groups, but software engineers and BCA/BE are not significantly different from each other. The different educational qualification accounts for 4.2% of the variance in the employee job satisfaction.

The table also points out the statistically significant effect of educational qualification on employee OCB, F = 6.097 (3,402), p = 0.000. A post hoc comparison using the Tukey HSD test indicates that the mean score of MCA/ME (M = 2.97, SD = 0.79) is significantly different from all other educational qualification groups. Remaining groups, software engineers (M = 3.44, SD = 0.69), BCA/BE (M = 3.43, SD = 0.63) and computer engineers (M = 3.30, SD = 0.59), do not differ significantly from each others. Different educational qualification accounts for 4.4% of the variance in employee OCB.

There is a statistically significant effect of educational qualification on employees' POS, F = 5.144 (3,402), p = 0.002. A post hoc comparison using the Tukey HSD test indicates that the mean score of MCA/ME (M = 2.71, SD = 1.51) is significantly different from other educational qualification groups. Educational qualification group, namely, software engineers (M = 3.03, SD = 1.61) and BCA/BE (M = 3.11, SD = 1.58), is also significantly different from other groups, but computer engineers (M = 2.90, SD = 1.52), is not significantly different from MCA/ME, software engineers and BCA/BE. The different educational qualification accounts for 3.7% of the variance in the employees POS.

It is interesting to note that employees' TI is not significantly related to employees educational qualifications as evidenced by p > 0.05 (p = 0.454). It is concluded that there is no significant difference between the groups. A post hoc test cannot be conducted to find out the difference between mean groups as they all are similar to each other about employee TI. The result of One-way ANOVA suggests partial support for H1.

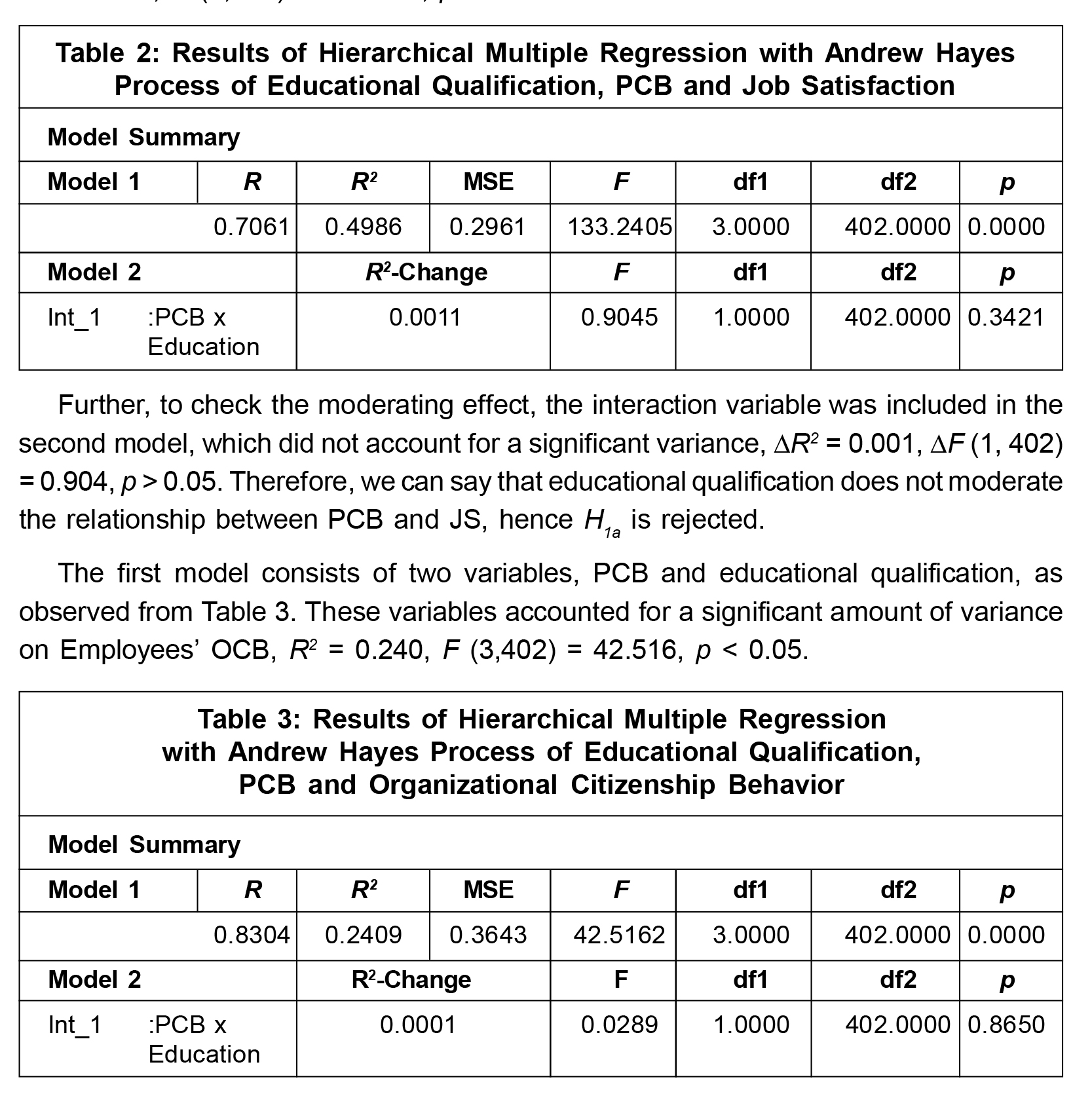

Table 2 presents the results of Hierarchical Multiple Regression (HMR) with the Andrew Hayes Process. In the first model, two variables of PCB and educational qualification were included. These variables showed a significant level of variance in employees JS, R2 = 0.498, F (3,402) = 133.240, p < 0.05.

Further, to check the moderating effect, the interaction variable was entered, which did not account for a significant variance, DR2 = 0.000, DF (1, 402) = 0.028, p > 0.05. Therefore, we can conclude that educational qualification does not moderate the relationship between PCB and OCB, and hence H1b is rejected.

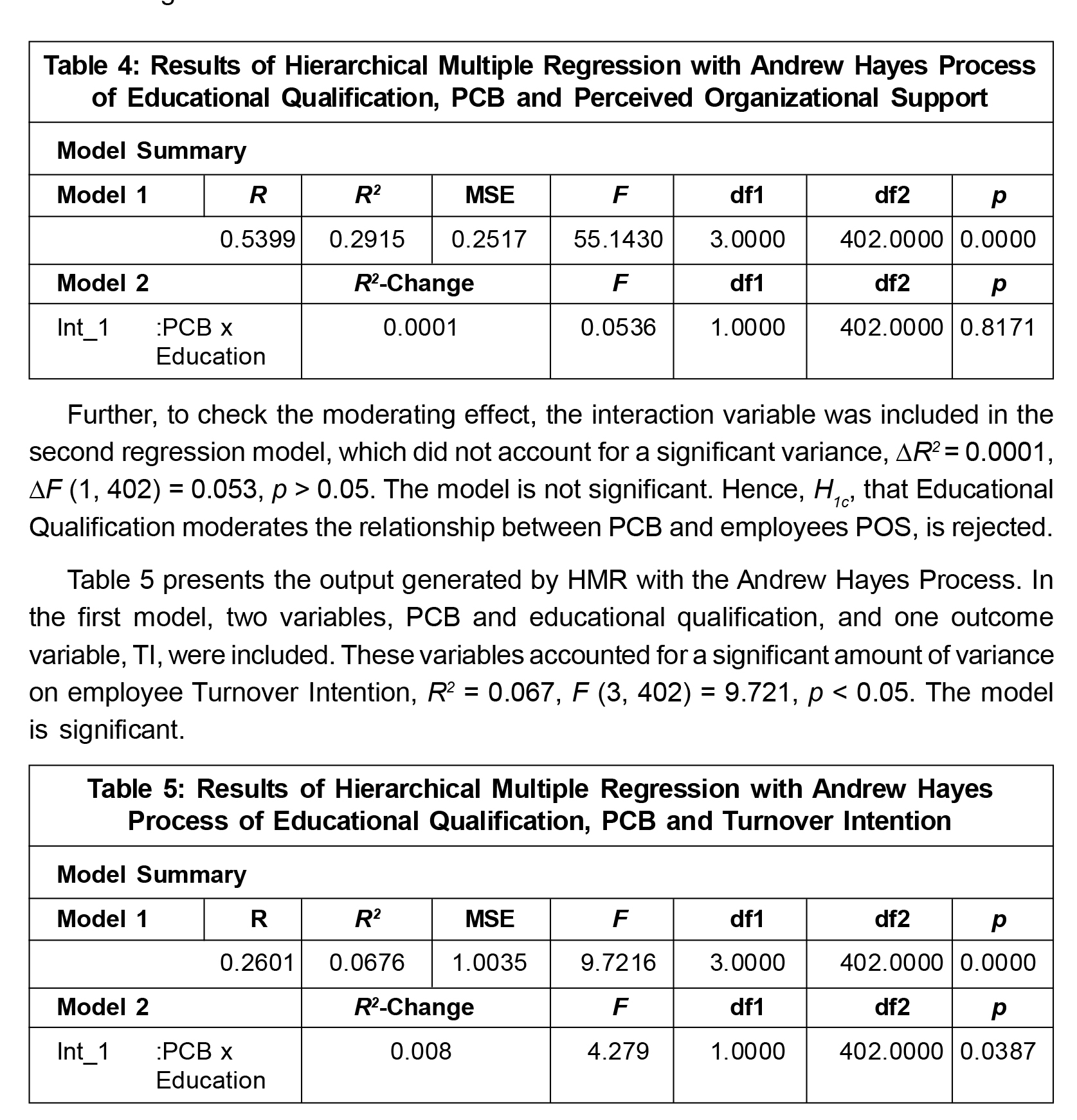

The first model comprises two variables, PCB and educational qualification and one outcome variable POS, as seen in Table 4. These variables accounted for a significant amount of variance on employees POS, R2 = 0.291, F (3,402) = 55.143, p< 0.05. The model is significant.

Secondly, to check the moderating effect of educational qualification on the relationship between PCB and TI, the interaction variable was included in the second regression model, which did account for a significant variance, DR2 = 0.008, DF (1, 402) = 4.279, p < 0.05; this indicates that educational qualification moderates the relationship between PCB and TI. Therefore, H1d is accepted.

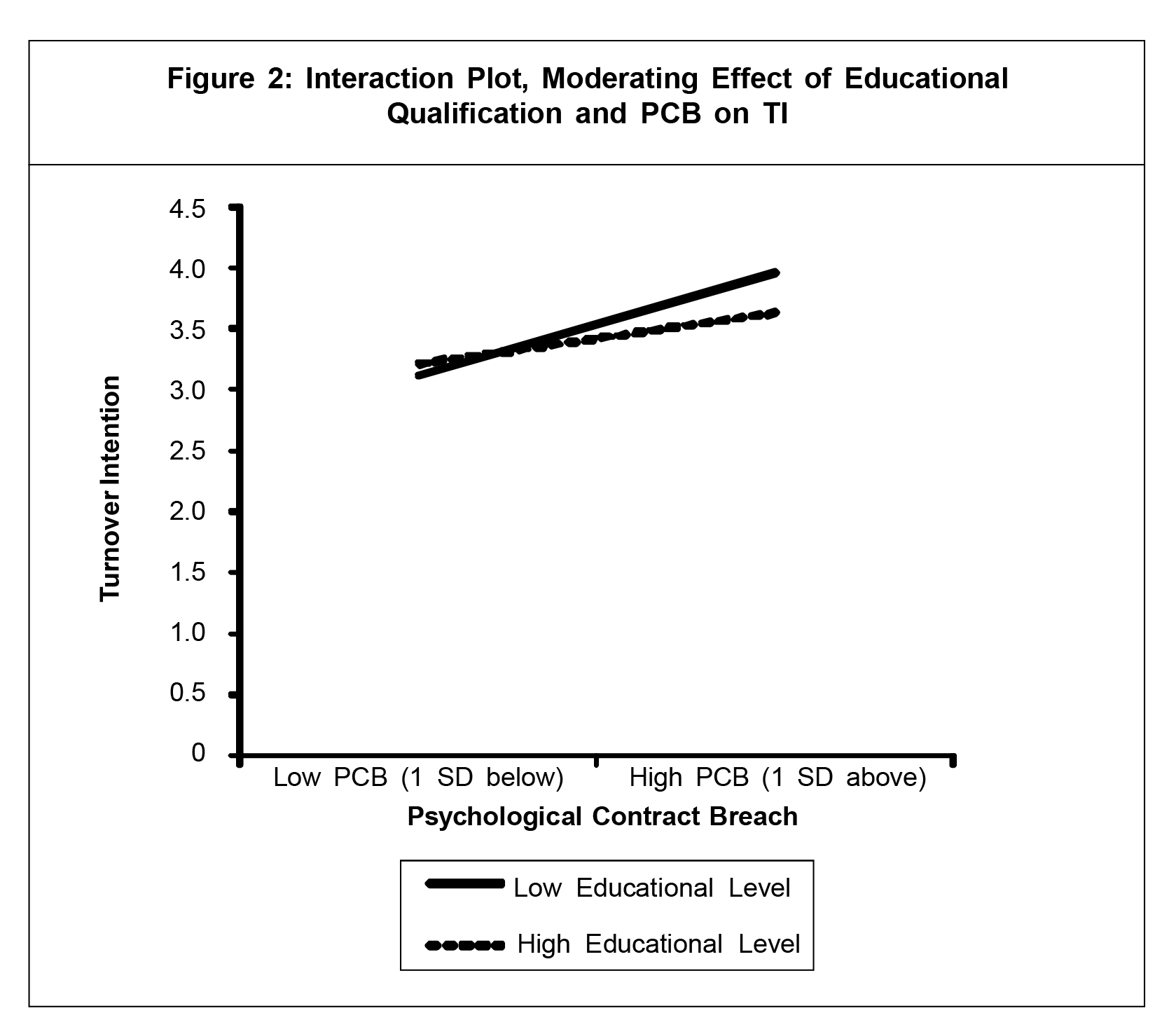

To gain further insights into the nature of the interaction effect, Aiken (1991) suggested plotting the slopes for high (one standard deviation above the mean) and low (one standard deviation below the mean).

Discussion

Non-fulfillment of assured incentives is viewed as the breach of psychological contract and activates harmful responses from employees. When the organization is perceived to incompetently fulfill its promises, employees view their exchange with the organization as less valued and respond by declining their level of citizenship behavior, satisfaction and perceived support as well.

Since PCB is a subjective concept (Rousseau, 1995), individual characteristics can aggravate or cushion the negative effects of contract breach on outcome (Rousseau, 1995; and Morrison and Robinson, 1997). The employees working in the IT sector have been referred to as Knowledge Workers because they are highly qualified. Employees who have been exposed to extra years of learning are more likely to expect more from their employers. The study attempted to find the moderating effects of education on PCB-Outcome relationship. Employees with higher educational level respond more emotionally to occurrences of breach in terms of intention to leave the organization. These findings validate with the school of thought which proposes that employees with higher educational level tend to have higher expectations in terms of inducements from their organization (Bellou, 2009). We cannot overlook the fact that employees with lower educational levels shall look for greater support from colleagues, but this may not be applicable in the IT industry where the workers are highly qualified.

Although the sample includes five categories, they have been classified into two groups for the Interaction plot. The first group of Low Level of Educational Qualification consists of Diploma in IT, BCA, MCA, and the second group of High Level of Educational Qualification comprises Computer Engineer and Software Engineer, for plotting the interactions. Visual inspection of the interaction plot, as seen in Figure 2, shows an enhancing effect, which means as the educational level increases, the effect of PCB on Turnover Intentions also increases. Possible inferences could be that the workers who feel overqualified in their present job position are less satisfied because their expectations have not been fulfilled or they think that they should be holding more satisfying or less stressful jobs. On the other hand, workers with a job related to their educational qualifications are more satisfied because they make use of their knowledge and skills acquired in educational institutions.

The study also reiterates the importance of attracting and retaining knowledgeable professionals in IT companies. For this, a work environment that provides sufficient prospects for learning and an incentive system that is based on a crystal-clear performance measurement structure must be in place. Such an arrangement requires facilitative leadership in IT companies and needs to have an open communication system by encouraging formal and informal meetings and teamwork encouragement. If not taken care of, this may result in employee burnout, further adding to the high attrition rate.

Conclusion

The IT sector is a significant and growing industry. Especially in India, it has played a major role in the economic development of the country. The present study concludes that the IT sector workforce in India is experiencing a high level of PCB, which could be the reason for the high attrition rate. Similarly, the employee outcomes examined shows a low level of Job Satisfaction, OCB, POS and higher level of Turnover Intentions. The negative consequences of non-fulfilment of employee expectations are likely to go beyond the hurt feelings and disillusionment felt by employees, which may result in damaging the organization's reputation as well.

The results are in line with Social Exchange Theory. The study confirms the strong association between employee perception of PCB and high Turnover Intention. When employees perceive that their psychological contract has been breached, they respond to this breach by decrease in Job Satisfaction, OCB and POS.

The relationship between the level of education and job satisfaction was somewhat ambiguous in the earlier studies. This study found that educational qualification has significant influence on Job Satisfaction, Relational Psychological Contract, OCB, and POS, but not on Turnover Intentions. However, educational qualification moderates the relationship between PCB and employee intention to leave the organization.

Theoretical Contributions

The findings of this study significantly contribute to the advanced body of knowledge in understanding the philosophy of the unwritten/implicit/mutual contract called the psychological contract. Future research is expected to focus on the role of demographic characteristics in influencing psychological contract. In addition, most of the studies on psychological contract have focused on direct effects of breach on organizational outcomes, which has been considered as a serious literature gap. By examining the moderating effects of employee educational levels, this study has revealed some thought-provoking findings in the PCB-Outcome relationship. This novel theoretical framework offers a more sophisticated clarification of the connection between PCB and employee attitudes in a fresh geographical setting. The complex business environment plays a crucial role in determining employment relationship and will continue doing so. The study provides us an enhanced understanding of why and when employees are expected to react negatively and under what circumstances such a negative response can be minimized or avoided.

A significant observation to be noted is that Indian employees, like their Western counterparts, perceive their psychological contracts to have been breached, as rightly concluded by the results of this study. The organization has to handle the issue proactively rather than keeping on justifying their side about breach. The employers have to be cautious about what they promise to the job applicant especially during the recruitment process. In order to have a mutual explanatory framework, organizations can make Realistic Job Previews (RJPs) as a vital part of their recruitment plan.

Organizations are becoming more flexible and fragmented, focusing on individualistic values. Examining the PC will help to develop human resource policies that will take care of individual-organization linkage, positive leader-management exchange, and combined pervasive change. The results of this study also reveal that the desirable type of PC varies based on group membership, namely, level of education. Organizations should therefore be aware that employee work attitudes are influenced by their education level. Therefore, there is an urgent need to have a comprehensive framework that will help the organization to solve the complex problem of Human Resource Management, taking into consideration the educational level of employees.

Limitations and Future Scope: The major limitation of the study is common method variance because the data were collected via employees' self-reports. Future research can reduce this limitation by collecting data from multiple sources such as peer or supervisor report on employee performance. Secondly, the data set provides a perception on the employment relationship in the Indian context only. The employees surveyed belong to different IT companies in Indian working environment. Therefore, enough care has to be exercised before the generalizability of the findings. Nevertheless, it can be expected that employees experiencing PCB will react in identical way. Finally, there are other organizational and individual characteristics such as tenure, organizational size, stage in career, personality, work status, etc., which may also influence their perception about PC and outcomes, which requires due consideration in future studies.

Adequate research has now been directed towards the importance of understanding PC at the workplace. PC shall remain an important subject, as the current employment relationship continues to undergo major transformations in terms of layoffs and reorganization. There are many unanswered questions that need future research attention. Future research should focus on investigating the diversity of PC among different groups of employees. PC does not remain the same; it goes through many changes over a period of time. Researchers need to tap these changes for effective management of workforce. Additionally, studies need to discover how PC developers at the workplace, to what extent they are shared, which elements of the PC are most appreciated, and which are more prone to experience a breach.

References

- Agarwal U A and Bhargava S (2013), "Effects of Psychological Contract Breach on Organizational Outcomes: Moderating Role of Tenure and Educational Levels", Vikalpa, Vol. 38, No. 1, pp. 13-25.

- Aiken W (1991), Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions, Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA.

- Algamdey N (2021), "Employees' Perceptions of Psychological Contract Breach and Their Turnover Intention", Palarch's Journal of Archaeology of Egypt/Egyptology, Vol. 18, No. 14, pp. 359-371.

- Anwer N, Rashidi M Z and Hamid S A (2020), "A Review on Psychological Contract and Psychological Contract Breach: Addressing Missing Link in the Context of Developing World", International Review of Social Sciences, Vol. 8, No. 7, pp. 27-34.

- Aselage E (2003), "Perceived Organizational Support and Psychological Contracts: a Theoretical Integration", Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 24, pp. 491-509.

- Bahadyr F, Yes M, iltas Sesen H and Olaleye B R (2022), The Relation Between Perceived Organizational Support and Employee Satisfaction: The Role of Relational Psychological Contract and Reciprocity Ideology, Kybernetes, Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Ballou N (2013), The Effects of Psychological Contract Breach on Job Outcomes, San Jose State UniversityProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

- Baral R and Bhargava S (2010), "Workfamily Enrichment as a Mediator Between Organizational Interventions for Worklife Balance and Job Outcomes", Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 25, No. 3, pp. 274-300.

- Beck P (2006), "The Content Validity Index: Are You Sure You Know What's Being Reported? Critique and Recommendations", Research in Nursing & Health, pp. 489-497.

- Bellou (2009), "Profiling the Desirable Psychological Contract for Different Groups of Employees: Evidence from Greece", The International Journal of Human Resource Management, pp. 810-830.

- Blau P M (1964), Social Exchange, International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences.

- Botha L and Steyn R (2021), "Conceptualisation of Psychological Contract: Definitions, Typologies and Measurement", Journal of Social Science Studies, Vol. 8, No. 2.

- Budhwar P, Tung R, Varma A and Do H (2017), "Developments in Human Resource Management in MNCs from BRICS Nations: A Review and Future Research Agenda", Journal of International Management, Vol. 23, No. 2, pp. 111-123.

- Burris (1983), "The Social and Political Consequences of Overeducation", American Sociological Review, Vol. 48, No. 4, pp. 454-467.

- Clark K and Oswald A (1995), "Satisfaction and Comparison Income", Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics.

- Clark A and Oswald A (1996), "Satisfaction and Comparison Income", Journal of Public Economics, Vol. 61, No. 3, pp. 359-381.

- Conway N and Briner R B (2009), "Fifty Years of Psychological Contract Research: What do we Know and What are the Main Challenges", International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Vol. 24, April, John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- Coyle-Shapiro J (2000), "Consequences of Psychological Contract for the Employment Relationship: A Large Scale Survey, Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 37, No. 7, pp. 903-930.

- Dello Russo, Vecchione and Borgogni (2013), "Commitment Profiles, Job Satisfaction, and Behavioural Outcomes", Applied Psychology, Vol. 62, No. 4, pp. 701-719.

- Eisenberger R, Huntington R, Hutchison S and Sowa D (1986). "Perceived Organizational Support", Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 71, No. 3, pp. 500-507.

- Engellandt A R (2003), "Temporary Contracts and Employee Effort", Institute for the Study of Labor, IZA Discussion Papers, No. 780.

- Francisco G, Sanchez S M and TomasLopez-Guzman (2016), "The Effect of Educational Level on Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment: A Case Study in Hospitality", International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration, Vol. 17, No. 3, pp. 243-259.

- Gakovic A and Tetrick L E (2003), "Psychological Contract Breach as a Source of Strain for Employees", Journal of Business and Psychology, Vol. 18, No. 2, pp. 235-246.

- Gaziogl S and Tansel A (2006), "Job Satisfaction in Britain: Individual and Job Related Factors", Applied Economics, Vol. 38, No. 10, pp. 1163-1171.

- Glenn N D and Weaver C N (1982), Further Evidence on Education and Job Satisfaction, Vol. 61, No. 1, pp. 46-55, The University of North Carolina Press.

- Guest D (2004), "The Psychology of the Employment Relationship: An Analysis Based on the Psychological Contract", Applied Psychology: An International Review, Vol. 53, No. 4, pp. 541-555.

- Guest D (2017), "Human Resource Management and Employee Well-Being: Towards A New Analytic Framework", Human Resource Management Journal, Vol. 27, No. 1, pp. 22-38.

- Hall R H (1994), The Sociology of Work: Perspectives, Analyses and Issue, Pine Forge Press.

- Hammett (1984), "The Changing Work Environment", Employment Relations Today, pp. 297-304.

- Hartmann N and Rutherford B (2015), "Psychological Contract Breach's Antecedents and Outcomes in Salespeople: The Roles of Psychological Climate, Job Attitudes, and Turnover Intention", Industrial Marketing Management, Vol. 51, pp. 158-170.

- Joshy and Srilatha (2011), "Psychological Contract Violation and its Impact on Intention to Quit: A Study of Employees of Public Sector and Old Generation Private Sector Banks in India", Asian Journal of Management.

- Koys D J, Timothy K and Allen R E (1989), "Employment Demographics and Attitude that Predict Preferences for Alternative Pay Increase Policies", Journal of Business and Psychology, Vol. 4, No. 1, pp. 27-47.

- Luc-Sels J, Maddy Janssens and Inge Van Den Brande (2004), "Assessing The Nature of Psychological Contracts: A Validation of Six Dimensions", Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 25, No. 4, pp. 461-488.

- Lydon R and Chevalier A (2002), "Estimates of the Effect of Wages on Job Satisfaction", CEPDP (531) Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics and Political Science, London, UK, ISBN 0753015528.

- Manriquez M R, Tellez M D and Guerra and J (2010), "Empowerment as a Predictive Indicator of Organizational Commitment in SMEs", pp. 103-125, Mexico City.

- Meyer J P, Allen N J and Smith C A (1993), "Commitment to Organizations and Occupations: Extension and Test of a Three-Component Conceptualization", Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 78, pp. 538-551.

- Meyer Stanley, Herscovitch and Topolnytsky (2002), "Affective, Continuance, and Normative Commitment to the Organization: A Meta-Analysis of Antecedents, Correlates and Consequences", Journal of Vocational Behavior, Vol. 61, No. 1, pp. 20-52.

- Miller L J and Brewerton P M 1999), "Contractors and their Psychological Contracts", British Journal of Management, Vol. 10, No. 3, pp. 253-274.

- Millward L J and Brewerton P M (2000), "Psychological Contracts: Employee Relations for the Twenty-First Century?", International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Vol. 15, pp. 1-62.

- Millward L J and Hopkins L J (1998), "Psychological Contracts, Organizational and Job Commitment", Journal of Applied Social Psychology, Vol. 28, No. 16, pp. 1530-1556.

- Morrison E W and Robinson S L (1997), "When Employees Feel Betrayed: A Model of How Psychological Violation Develops", The Academy of Management Review, Vol. 22, No. 1, pp. 226-256.

- Moss D H (1998), "The New Protean Career Contract: Helping Organizations and Employees Adapt", Organizational Dynamics, pp. 22-37.

- Mowday R, Porter L and Steers R (1982), Employee-Organization Linkages: The Psychology of Commitment, Absenteeism, and Turnover, Academic Press, New York.

- Organ (1997), "Organizational Citizenship Behavior: It's Construct Clean-up Time", Human Performance, Vol. 10, No. 2, pp. 85-97.

- Paille P and Dufour M E (2013), "Employee Responses to Psychological Contract Breach and Violation: Intentions to Leave the Job, Employer or Profession", Journal of Applied Business Research, Vol. 29, No. 1, pp. 205-216.

- Parks J M, Kidder D L and Gallagher D G (1998), "Fitting Square Pegs into Round Holes: Mapping the Domain of Contingent Work Arrangements onto the Psychological Contract", Journal of Organizational Behavior, pp. 697-730.

- Parks M L and Kidder D L (1994), "Till Death Us Do Part..., Changing Work Relationships in the 1990s", Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 19, pp. 637-647.

- Rigotti T (2009), "Enough is Enough? Threshold Models for the Relationship Between Psychological Contract Breach and Job-Related Attitudes", European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, Vol. 18, No. 4, pp. 442-463.

- Robinson S L (1996), "Trust and Breach of the Psychological Contract", Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 41, No. 4, pp. 574-599.

- Robinson S L and Morrison E W (1995), "Psychological Contracts and OCB: The Effect of Unfulfilled Obligations on Civic Virtue Behavior", Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 16, pp. 289-298.

- Rousseau D (1989), "Psychological and Implied Contracts in Organisations", Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, Vol. 2, No. 2, pp. 121-139.

- Rousseau D (1995), Psychological Contract in Organizations, Thousand Oaks, Sage.

- Rousseau D (1998), "The 'Problem' of the Psychological Contract Considered", Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 19, No. 1, pp. 665-671.

- Robinson S L and Rousseau D M (1994), "Violating the Psychological Contract: Not the Exception But the Norm, Journal of Organizational Behavior, pp. 245-259.

- Sankaranarayanan and Lingadkar (2020), "Psychological Contract of IT Sector Employees in India", Journal of Interdisciplinary Cycle Research, Vol. XII, No. VI, pp. 188-201.

- Sloane P and Williams H (1996), "Are "Overpaid" Workers Really Unhappy? A Test of the Theory of Cognitive Dissonance", Labour, Vol. 10, No. 1, pp. 3-16.

- Smith, Organ and Near (1983), "Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Its Nature and Antecedents", Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 68, No. 4, pp. 653-663.

- Smithson J and Lewis S (2000), "Is Job Insecurity Changing the Psychological Contract?", Personnel Review, Vol. 29, No. 6, pp. 680-702.

- Smulders (1999), "The Job Demands Job Control Model and absence Behavior: Results of a 3-Year Longitudinal Study", Work and Stress, Vol. 13, No. 2, pp. 115-131.

- Sunarta Titho, Kritanto and Setyaningsih (2022), "Antecedents and Consequences Psychological Contract Fulfillment", Jurnal Economia, Vol. 18, No. 2, pp. 148-158.

- Theodossiou, Vasileiou and Nikolaou (2005), "Does Job Security Increase Job Satisfaction? A Study of the European Experience", 2nd World Conference.

- Tsui P P (1997), "Alternative Approaches to the Employee-Organization Relationship: Does Investment in Employees Pay Off?", Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 40, No. 5.

- Tura A S (2020), "Determinants of Employee's Turnover: A Case Study at Madda Walabu University", Advances in Management & Applied Economics, Vol. 10, No. 2, pp. 33-59.

- Turnley W H and Feldman D C (1999), "The Impact of Psychological Contract Violations on Exit, Voice, Loyalty, and Neglect", Human Relations, Vol. 52, No. 7, pp. 895-922.

- Turnley W and Feldman D (2000), "Re-Examining the Effects of Psychological Contract Violations: Unmet Expectations and Job Dissatisfaction as Mediators", Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 21, No. 1, pp. 25-42.

- Verhofstadt E, Hans De Witte and Eddy Omey (2007), "Higher Educated Workers: Better Jobs but Less Satisfied?", International Journal of Manpower, Vol. 28, No. 2, pp. 135-151.

- Weick, Richard and Karl (1983), "Organizations as Information Processing Systems", Department of Management, Texas A&M University, Texas.

- Weiss D J, Dawis R V and England G W (1967), Manual for the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire, Minnesota Studies in Vocational Rehabilitation.