October'23

The IUP Journal of Organizational Behavior

Archives

Asset Creation Under MGNREGS: The Case of Tripura

Pritam Bose

Assistant Professor, Faculty of Management and Commerce, ICFAI University, Tripura, India; and is the corresponding author. E-mail: pritambose@iutripura.edu.in

Indraneel Bhowmik

Professor, Department of Economics, Tripura University, Suryamaninagar, Tripura, India.

E-mail: eyebees@gmail.com

The paper seeks to understand the success of Mahatma Gandhi Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS) in the state of Tripura, India, in terms of nature and trend of activities, and the benefits accrued to participating households. The study observes that the number of activities taken up under the scheme increased by more than threefold during the six-year study period, i.e., 2014-15 to 2019-20. The trend growth rate of the number of activities stood at 24.8%. Land development, irrigation and water conservation remained the most prominent works, thereby creating an overwhelming dominance of activities earmarked as public works relating to natural resources management in the state. Creation of rural infrastructure, particularly, building of rural roads and internal streets, was also found to be a premier activity. The work completion rate (WCR) was around 44% in 2014-15, but came down to 7.49% in 2019-20, suggesting strong and significant inter-year differences in the average WCR. We also found statistically significant inter-district variations in WCR.

The size of the Indian economy has increased from around 10,000 cr in 1950-51 at current prices to about 200 lakh cr in 2020-21, indicating a massive 2000-fold increase in current prices. Similarly, the per capita income has grown from around 275 to more than 125,000 per annum during the same 70 years. The growth in the Indian economy has been primarily due to the changed composition of the national income, with industry and services increasing their share over the years at the expense of the primary sector. However, the pattern of employment has witnessed a slower rate of change. The agricultural sector still remains the largest employer with almost 43% share of the total labor force, though contributing only about 15% of the national income. Further, more than 65% of the population lives in rural areas. As a result, the Indian economy is characterized by underemployment in rural areas and existence of a large number of poor people warranting government intervention for economic support and facilitation.

The first occurrence of a wage employment program on planned national scale in the country can be observed way back in 1961, when the rural works program (RWP) was launched in selected districts to generate employment to the poor in lean season. After that, a number of wage employment programs followed. The major programs have been Crash Scheme for Rural Employment (CSRE) and Food for Work Program (FFWP) in the 1970s, followed by the first all-India wage employment programs vis-a-vis National Rural Employment Program (NREP) and Rural Labor Employment Guarantee Program (REGP) launched in the 1980s and Jawahar Rozgar Yojana (JRY), Employment Assurance Scheme (EAS), and Jawahar Gram Samridhi Yojana (JGSY), i.e., the refurbished JRY in the 1990s. In 2001, another program was launched by merging the earlier schemes of EAS and JGSY named Sampurna Grameen Rozgar Yojana (SGRY). These schemes aimed at providing wage employment to the poor, marginal and vulnerable sections of rural areas who were often left out of the mainstream development process.

The Mahatma Gandhi Rural Employment Guarantee Act 2005 (NREGA) was considered to be a landmark in the history of social security legislation of independent India for being the first public service provisioning scheme enacted through the Parliament of India. The Act's objective is to enhance the livelihood security in the rural areas by providing a guarantee of 100 days wage employment to all the applicants of rural households in a fiscal year regardless of any conditionality, save the willingness of the adult family members of the household to perform unskilled manual work.

Tripura, the second smallest state in the north-eastern region of India, is predominantly rural and characterized by a heterogeneous mix of tribal and non-tribal population, aggregating to almost 37 lakh, according to Census 2011. Tripura's hilly topography and remote location have been a factor impairing transportation and communication within and outside the state. These, coupled with unemployment, extreme poverty, low capital formation, poor infrastructure facilities and lack of private sector employment, act as a major constraint for overall economic development of the state. Under these circumstances, the state government took an active interest in the implementation of MGNREGS and as a result, Tripura emerged as one of the best performers in the country for creating the highest average person-days per household per year since 2012-13.

The scheme provided a social safety net as well as an employment opportunity to the vulnerable groups of the society, including the scheduled castes (SC), scheduled tribes (ST) and women. The MGNREGS started its journey in Dhalai district in Phase-I, followed by South Tripura and West Tripura in Phase-II and North Tripura in Phase-III. However, in 2012, the civil administration structure in the state was redesigned and smaller districts were carved out from existing ones to increase the total tally to eight from four.

Tripura was one of the best performers in the country in the initial years for creating the highest average person-days per household per year from 2012-13 to 2014-15. In terms of the proportion of households with 100 days of work, the performance of Tripura has been substantially higher than the national average and has been in the range of 30-35% for most of the years in the previous decade. However, in terms of the proportion of women person-days, Tripura has a lower share than the national average, though marginal, for almost all the years considered. A major reason for this is the general lack of employment opportunities in many rural parts of the state where MGNREGS activity is the only option and the man in the household avails it. In terms of fund utilization also, Tripura appears to have done better than the national average. Thus, one can understand that MGNREGS has been an important component of the state economy and has been an area of interest for a variety of stakeholders.

Literature Review

The very nature of MGNREGS is the cause for the immense attention it draws from the academics, policymakers and the media. The scheme is functional today because of the fact that it has been strongly advocated by sections of the civil society and activists. In other words, a program of such a large-scale is bound to raise both criticism and accolades. It is true that a program of such magnitude will have numerous dimensions and has therefore emerged as an area of interest for many academicians, both from the country and abroad. Taking stock of all the studies is beyond the scope of the present study; nonetheless, in this survey study, we have taken into account some of the prominent literature pertaining to the objectives and goals of our study. Therefore, for the present purpose, we have divided literature into two sections, as discussed below:

Employment Generations Under MGNREGS

The employment generation aspect of MGNREGS has been the most discussed feature in the literature. That the scheme has been a phenomenal success in creating employment opportunities is beyond doubt. Nevertheless, the aspect of job creation and provision has varied across the country. Even though the number of days of employment has been less, yet the scheme has helped the participants from Bihar and Jharkhand in procuring food and daily consumption items. Indebtedness has reduced, and the scheme appears to have inculcated a new level of consciousness about the minimum wage entitlement (Pankaj and Sharma, 2008). Marginal improvement in indebtedness, consumption levels and savings among the sample households was visible in Uttarakhand also (Singh and Nauriyal, 2009). As noted earlier, the dimension of employment in the scheme varied across states, and in Kerala, it has been observed that all those who demanded job were provided with, though the number of days were less (Nair, 2009). In Andhra Pradesh, the participation of households in MGNREGS was influenced by the size of income from other sources, family size and landholdings. Yet, the income from it were spent on food, education and health security like other states (Kareemulla et al, 2009). Dreze and Khera (2009) noted that among the sample households working under MGNREGS, 81% lived in kaccha houses, 61% were illiterate and over 72% did not have electricity at home. There were large proportions of landless agriculture labor participating in MGNREGS, as were households who were self-employed in non-agriculture activities. These observations reflected that MGNREGS was addressing the economic needs of the most deserving and the marginalized households; accordingly, it was no surprise that there were recommendations for removal of the ceiling of 100 days of work as it had become a lifeline for millions of Indians (Venkatesh, 2009).

On the other hand, Jeyaranjan and Vijayabaskar (2009) found that MGNREGS and other welfare measures may have contributed to increasing the reserve price of labor, and MGNREGS has the potential to have a virtuous linkage with labor markets in the manufacturing sector as well. However, Panda et al. (2009) informed that large proportions of the surveyed workers felt happy after communicating with bank officials as their confidence level had increased after working in MGNREGS and interacting with several government officials.

It may also be noted that in Madhya Pradesh, increase in water supply level due to the numerous community and individual level activities under MGNREGS was found to have resulted in an increase in the irrigated lands, which in turn led to augmented crop production as well as crop diversity and thereby increased annual household income. The proportionate increase in irrigated land area was more in resource-poor districts as compared to resource-rich districts; as a result, both area and production of rabi crop and wheat increased significantly (IIFM, 2010). A report by Institute of Rural Management, Anand (2010) reflected that MGNREGS has provided an additional source of income to the families without any gender discrimination. Moreover, it has enhanced food security and provided employment opportunities for the unemployed, and on an average has a positive impact on the livelihood of the rural people. In Andhra Pradesh, positive and significant impacts of MGNREGS towards (i) consumption items; (ii) energy and protein intake; and (iii) household assets collection indicated a positive outcome of the scheme (Deininger and Yanyan, 2010). Apart from higher number of days of employment and wage, MGNREGS intervention increased crop yield substantially in Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand and also reduced the vulnerability of the small and marginal farmers (Banerjee and Partha, 2010). It may be interesting to note here that Jha et al. (2010), using a probit model, indicated that the probability of participation of a household in the scheme was more if the family size was large and if the land possession was less. They found from the primary data that more than three-fourths of the sample respondents were landless or nearly landless.

It has been projected that due to MGNREGS, public employment per prime-aged person increased by three days per month in those districts where the program was launched in the first phase with 200 districts (Imbert and Papp, 2011). The scheme is also responsible for monetization of wages, as many agricultural workers were earlier paid in kind (Thakur, 2011). Activities relating to natural resource management, particularly relating to water usage under MGNREGS, led to distinct changes in land use pattern as well as cropping pattern. Fallow lands were brought in. However, the work on irrigation structures had helped in reducing the expenses on irrigation in West Bengal. In Madhya Pradesh, there was a shift from traditional to cash-crop due to improved irrigation facility.

It may also be noted that in addition to providing employment, the scheme has contributed to increasing financial inclusion by ensuring wage payments through bank accounts and post offices as observed in many states including Rajasthan. Jain and Raminda (2013) considered MGNREGS as the benchmark of social security and appreciated the vast scope of the program and its impact on the livelihood security of the rural poor. But the authors felt that the government should strictly discourage educated people from undertaking unskilled labor under MGNREGS. The social contribution of the scheme is attested to by the fact that in Haryana participants opined that MGNREGS helped them to increase the expenditure on education of their children and for medical purposes (Arora et al., 2013). It is said that the economically weaker states of the country have benefitted the most and have implemented the scheme more vigorously. Increased income led to increase in food consumption viz-a-viz both cereals and non-cereals by all the categories of households; further, better calorie intake reduced undernourished and nutrition-deficit households by 8% to 9% (Kumara and Joshi, 2013).

The varied outcome of the scheme manifested in the fact that analysis of district level data from 2008 to 2013 shows that introduction of the scheme led to a 3% increase in night time lights, and most importantly a 13% increase in bank deposits. However, an area of concern remains: the positive effects of the scheme are mostly driven by richer districts, indicating the issue of inequality (Cook and Manish, 2020). Moreover, another area of concern is MGNREGS wage rates of 17 states out of 21 states are even lower than the state minimum wage rate for agriculture, with Jharkhand lagging at the bottom (Aggarwal and Vipul, 2020).

Asset Creation

Mehrotra (2008) observed that MGNREGS aimed to create durable and sustainable assets which would be environment-friendly. Around 49% of works were related to water conservation and extremely important for reduction of rural poverty. Moreover, the roads constructed under MGNREGS have helped the people immensely and will contribute to the development of the region.

The assets created under MGNREGS in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands included construction of footpaths, proper drainage system in water-logging areas, small check dams, digging of ponds and wells, renovation of traditional tanks and ponds, and land development for socially useful purposes (Bannerjee, 2009). MGNREGS works have also helped in increasing production in the study areas of HP and Haryana, but did not have much positive impact in Punjab (CRRID, 2009). Further, Kareemulla et al. (2009) observed that soil and water conservation works (SWC) in Andhra Pradesh helped in improving the livelihood of the participating households.

Road construction, digging of wells, water-related activities and tree planting were the most common types of assets created through MGNREGS in Madhya Pradesh. However, these community assets have had varying impact, including the facilitation of greater crop production and better marketing of products as a result of improved infrastructure (Sadana and Rath, 2010). The increased access to physical and natural assets like improved roads, soil/water conservation structures, farm ponds, and community tanks strengthened livelihood system and promoted people's participation in the development process through community-based organizations such as Palli-Sabha, Gram Sabha, VSS, Social Audit and Vigilance Committee, Pani-Panchayat, etc. (Center for Rural Development, 2010). However, the states need to guarantee a better mechanism for the durability and sustainability of assets created under MGNREGS (IRMA, 2010). It was seen that the assets created on individual land were being monitored properly and the quality of those assets were also very good. However, assets created on community land were of inferior quality and lacked maintenance. Proper monitoring was needed for better utilization of assets created (Mishra, 2011). It may be noted that good quality assets were created under MGNREGA in HP (Vaidya and Singh, 2011).

Moreover, UNDP (2013) reported that MGNREGS had helped in generation of extra income for a majority of households through creation of assets, and a substantial number of households were able to settle themselves in alternative sources of employment. In Jharkhand, a very large proportion (80%) of the works under MGNREGS focused on soil and water on the lands of the small and marginal farmers (Singh, 2013). Many households that sought employment under MGNREGS did not come back for MGNREGS works once their own land assets were revitalized. Further, most of the people were under the impression that development of roads was the most important impact, followed by increase in surface water.

Narayanan et al. (2014) conducted a survey across 100 villages spread over 20 districts in Maharashtra and found that 87% of work in Maharashtra still existed and 75% of these were directly or indirectly related with agriculture. Horticulture works favored the better endowed farmers with substantive addition to the existing resource base and infrastructure in the form of new roads. Moreover, water conservation and harvesting structures had emerged where water scarcity was the norm. It may be noted here that more than 90% of the field respondents considered the works undertaken under MGNREGS as very useful or somewhat useful. The widespread perception that the scheme does not create any productive assets appears to be not valid in the surveyed areas of Maharashtra, although there is scope for improving the choice, quality and execution of the works (Kulkarni

et al., 2015).

Objective

In this backdrop, the objectives of the paper are:

- To analyze the nature and trend of activities under MGNREGS

- To examine the benefits accruing to the household from the assets created by the scheme.

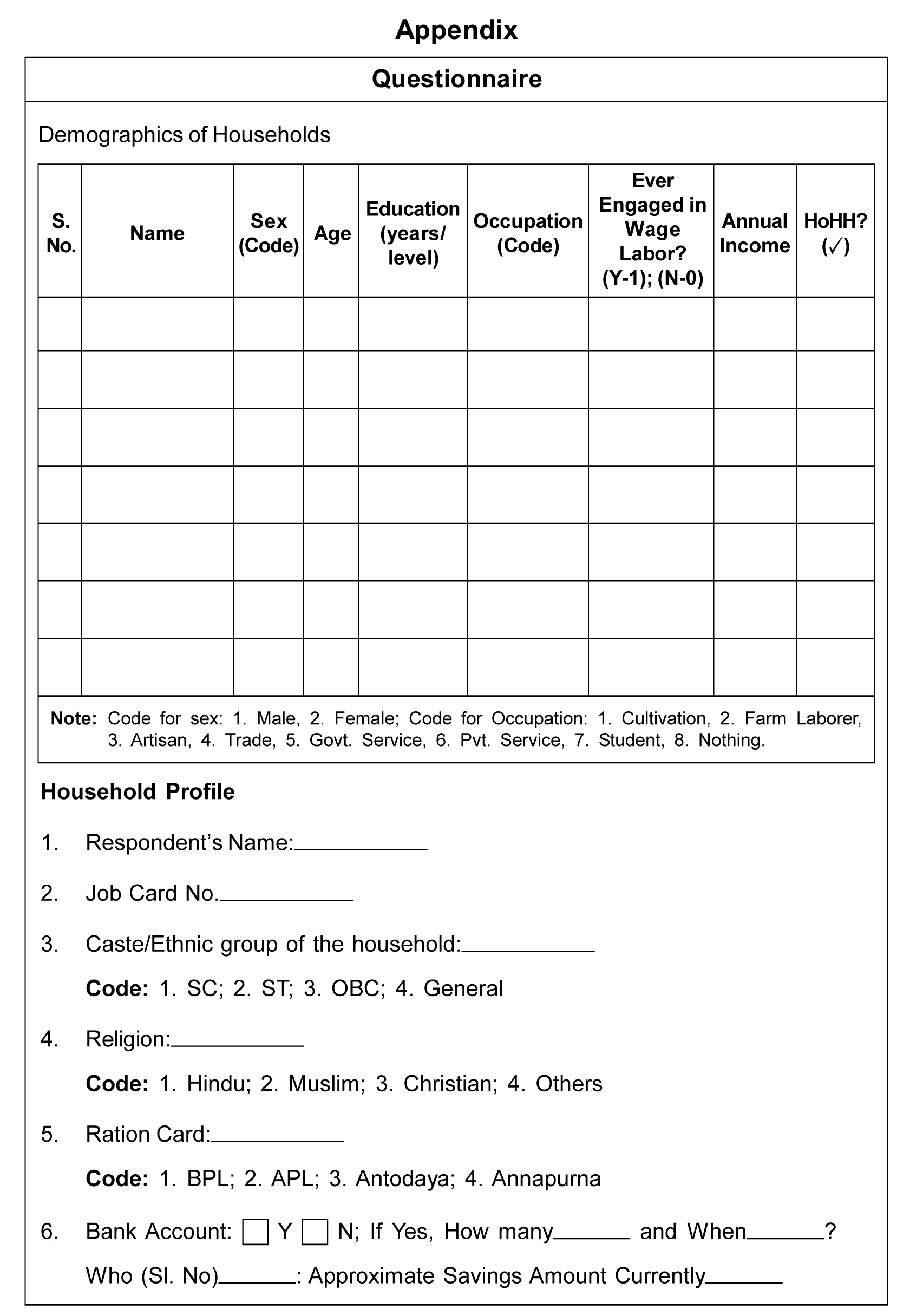

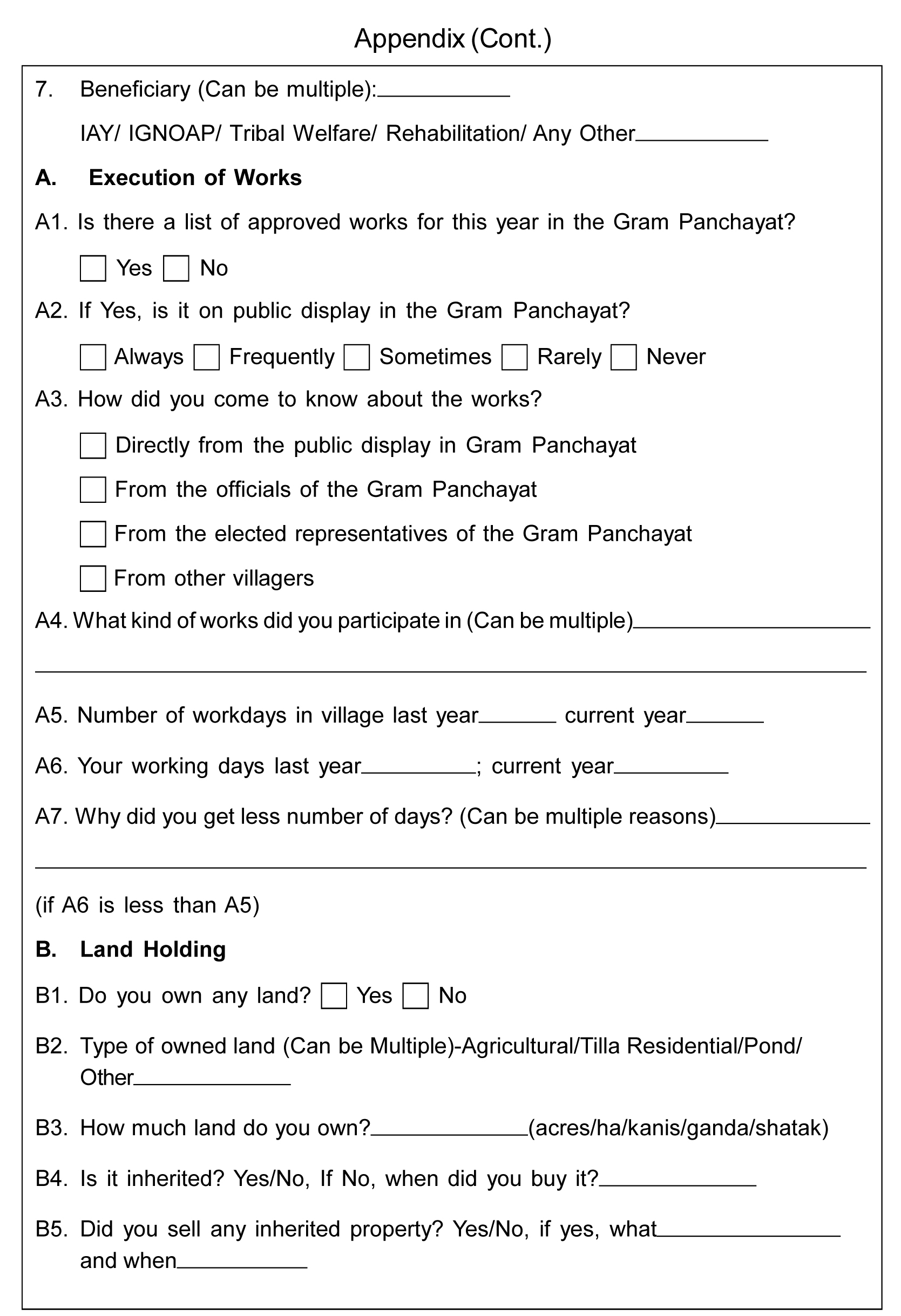

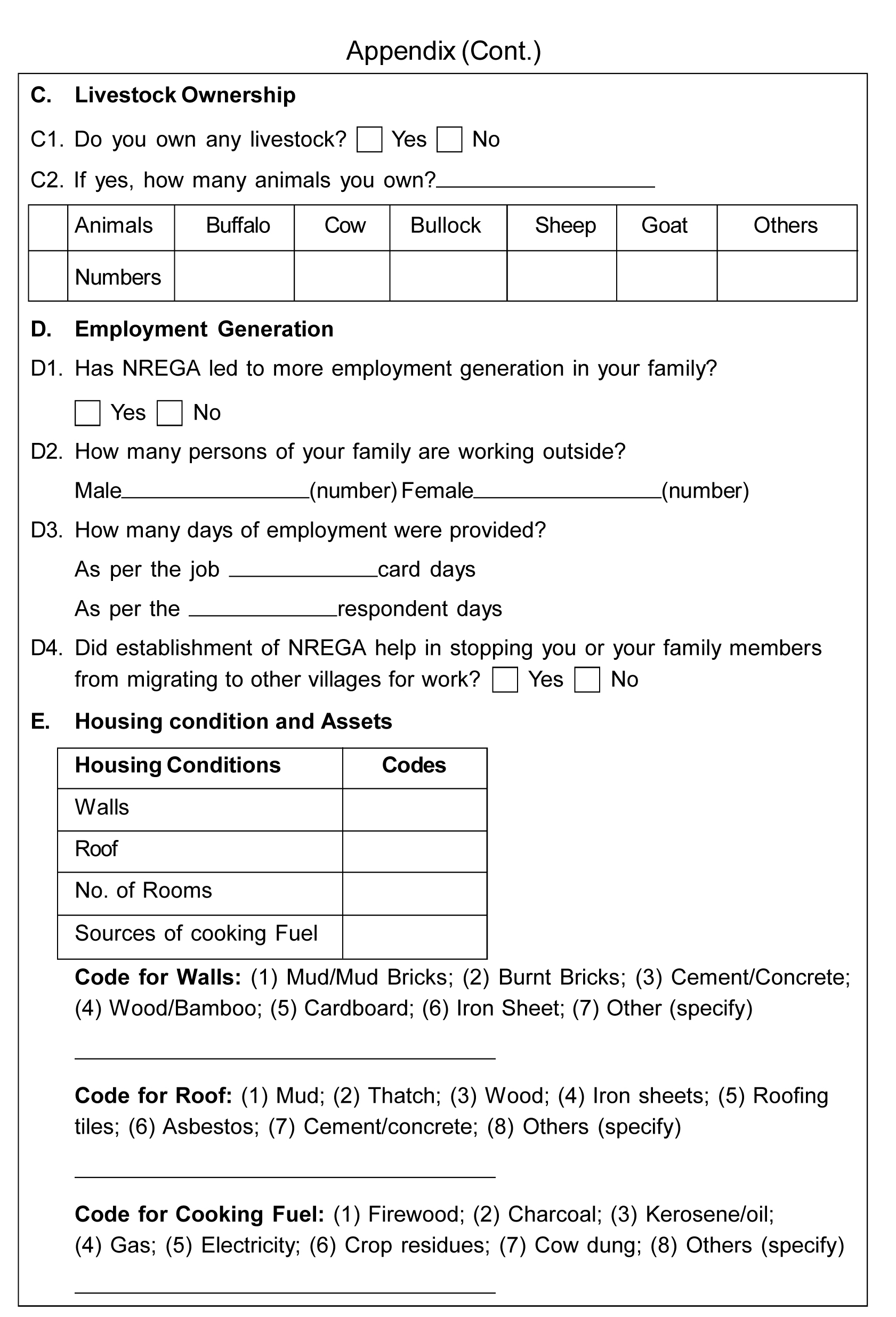

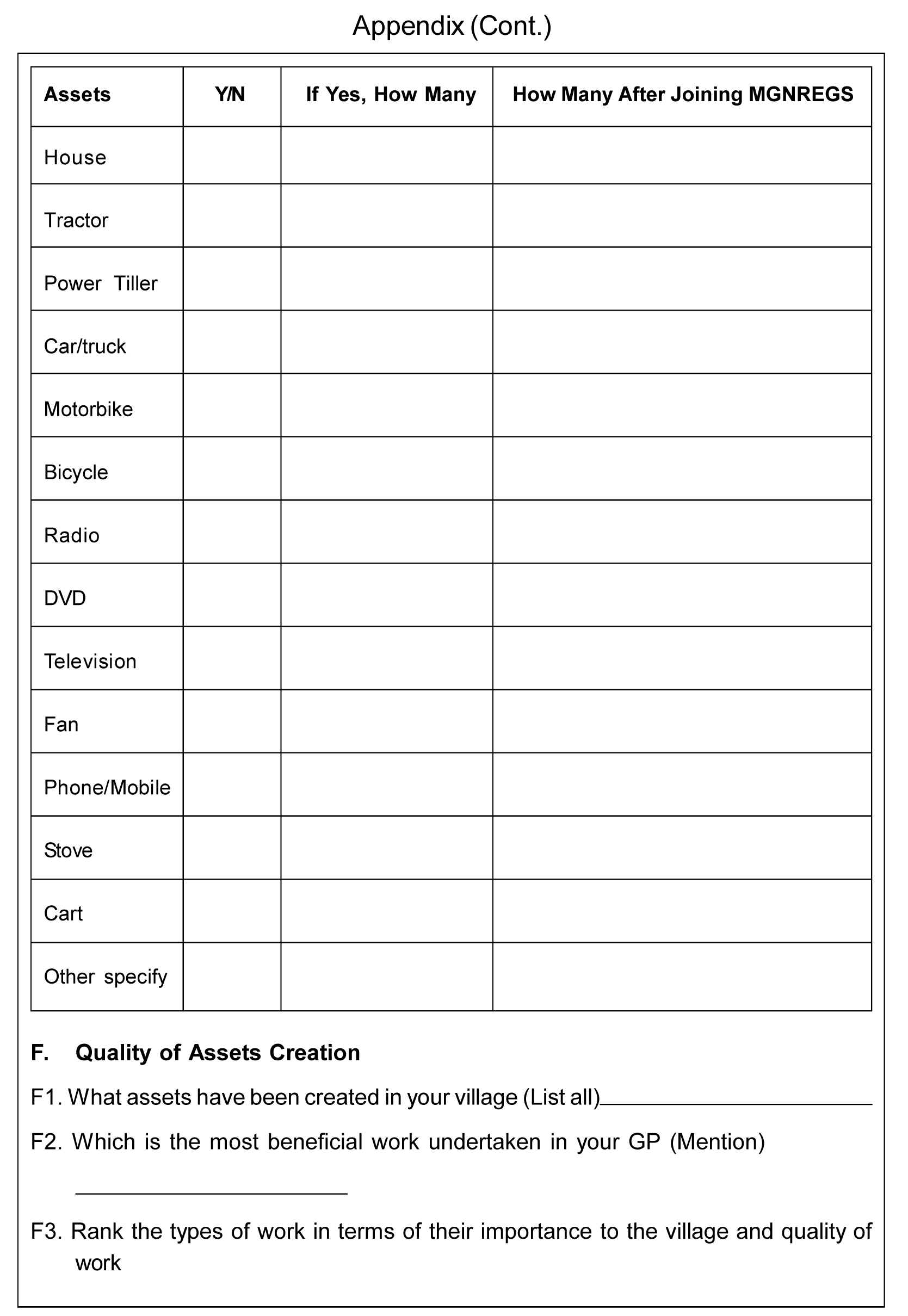

The present study uses both primary and secondary data to address the stated objectives. The first objective of the paper is based on secondary data. Here, the secondary data will enable us to draw a clear picture regarding the kind of activities carried out, nature of these asset-created activities, types of works given more priority, etc. On the other hand, the second objective of the paper is based on primary data collected from a representative sample of households through field survey following appropriate design and techniques. Information regarding the importance, quality and the nature of the assets created through MGNREGS activities was collected and the respondents were asked to rank the top three beneficial assets in their area created through MGNREGS. Here one thing should be noted: the scheme accommodates both public and private assets. Public assets are those assets whose benefits are enjoyed by the locality, whereas private assets are those whose benefits are enjoyed by the individual specifically. Hence, data on both public and private assets has been collected and analyzed. A multi-stage random sampling procedure was adopted. In the first stage, two districts of Tripura were randomly selected-Dhalai and West Tripura. From each district, two RD blocks were randomly selected-in Dhalai, the two RD blocks were Durga Chowmuhani and Manu; while in West Tripura, the RD blocks were Dukli and Mohanpur. In the next stage, two Gram Panchayats (GPs) were selected, of which one was an ST majority and fell under TTAADC areas, while the other was an unreserved one. The two villages of Durga Chowmuhani blocks were Kalachari and Dhan Chandra Para and the two GPs from Manu RD block were Manu GP and North Mainama GP. The two GPs under Dukli RD block were East Jarubachai and Khas Madhupur, while Fatikcherra and Rangachara were the two GPs from Mohanpur RD block. From each GP, 10% of the participating households were randomly selected and information from them was collected using a semi-structured questionnaire (see Appendix). The total sample size was 418. The study was conducted in the year 2018.

The study used standard statistical measures like ANOVA (two-way without replacement), and average annual growth rates were applied for drawing analytical insights alongside simple tools like percentage and charts like Box Plot. For better comprehension, data for the 8 districts and 58 Rural Development Blocks were used and analyzed.

Significance

The surveyed literature focuses on a lot of issues pertaining to implementation, functioning, efficiency and equity of the scheme. The scheme hopes to solve the short-term problem of unemployment by creating employment generation through asset creation. As a result, the scheme provides such a situation where these two indicators should run in tandem to fulfil the desired objective, i.e, employment generation and asset creation. It is in this backdrop that the present study examines the nature and trend of activities carried out under the scheme. Moreover, the benefits availed by the households from the creation of assets have also been addressed.

Results and Discussion

Asset creation under the scheme is always an important objective and is the second-most important objective of the scheme. The nature and trend of activities under the scheme at the block level of Tripura is the first objective of the study. In this context, we have considered and examined different types of works undertaken, work completion rate, and most beneficial activities, using the secondary data from the official website of the scheme.

The most important part of the scheme lies in the twin objectives of employment generation and asset creation in the rural areas and thereby a multiplier effect on the economy in terms of effective demand generation and subsequent production boost.

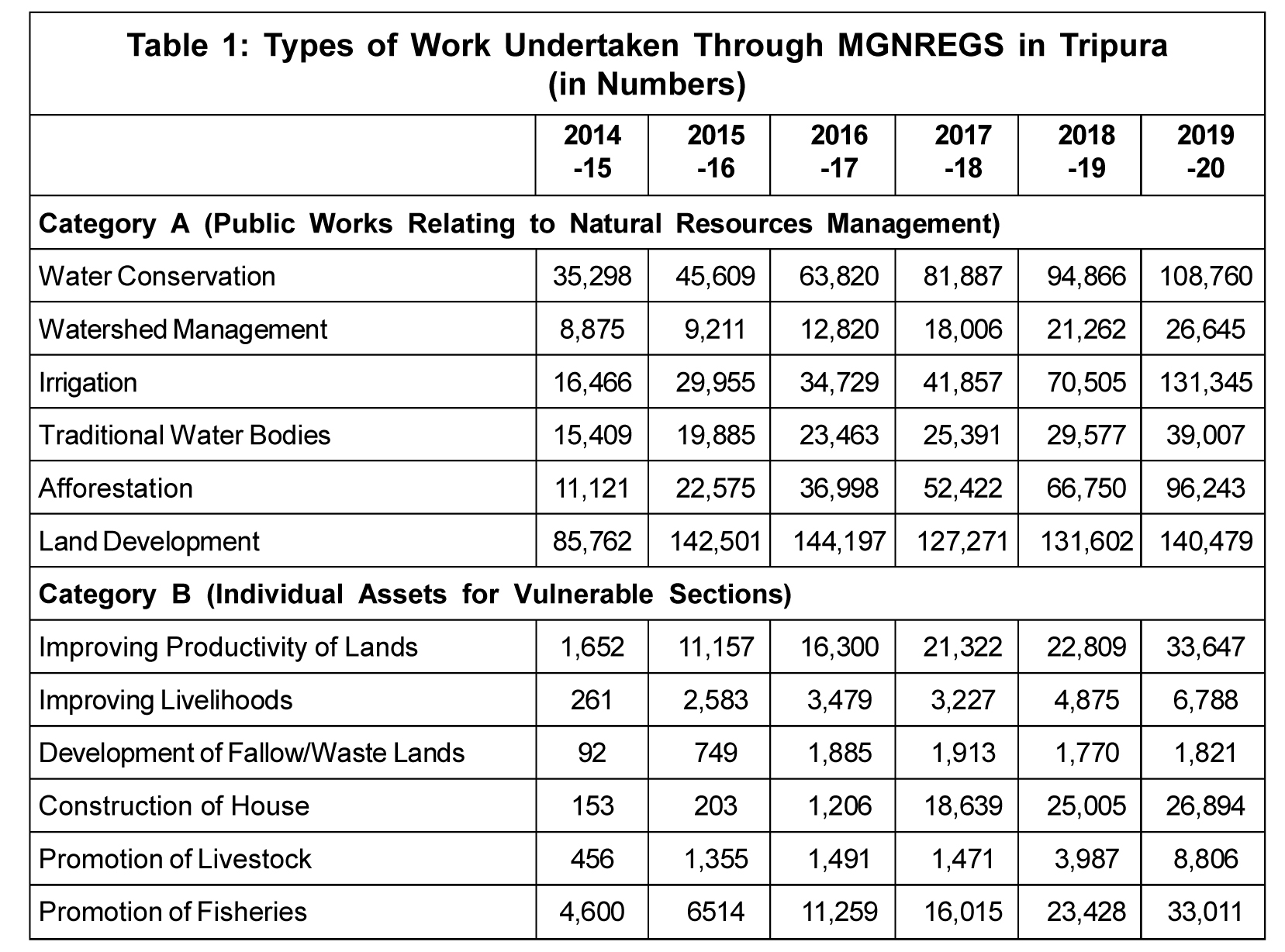

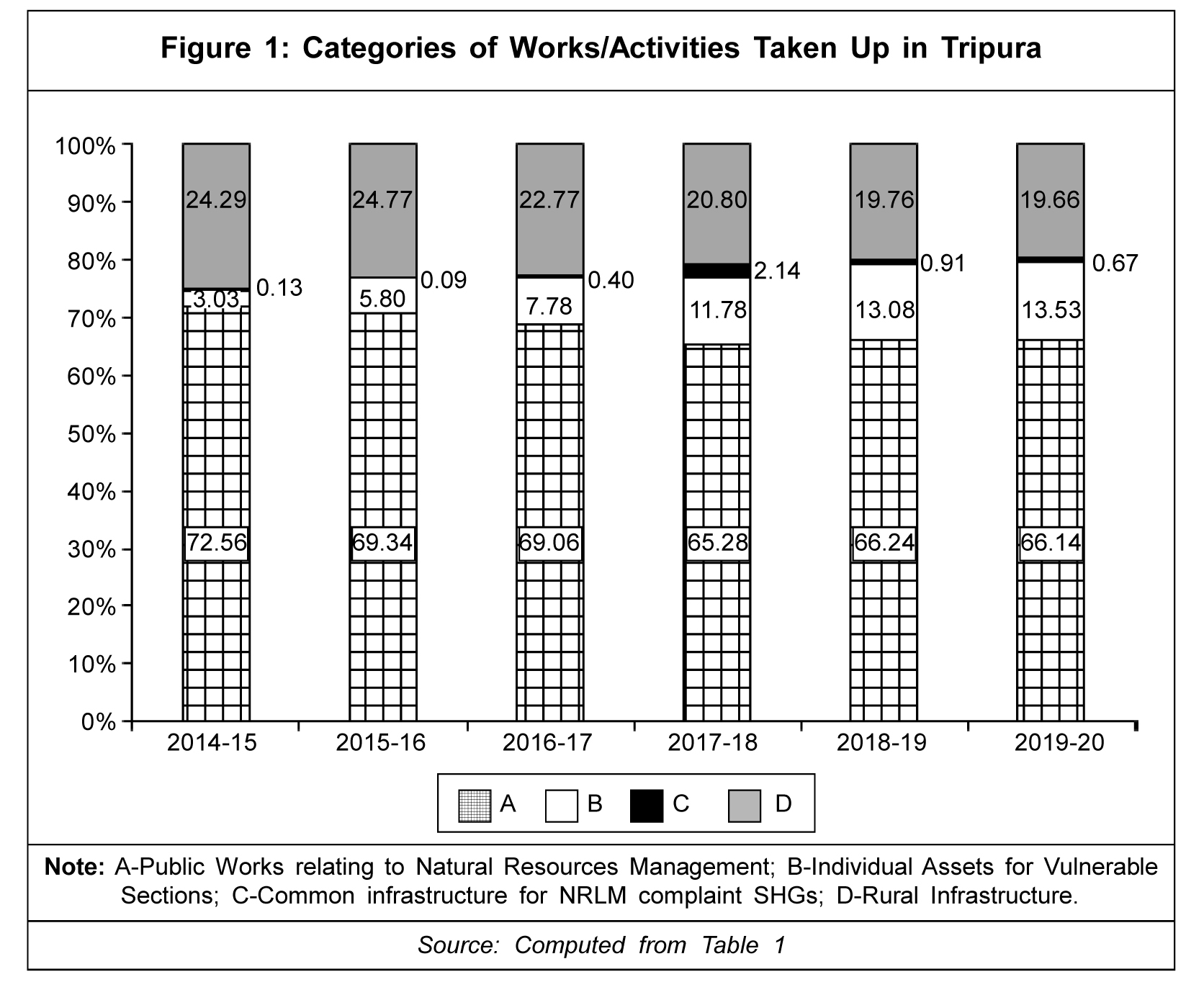

Table 1 shows that the number of activities in the state increased manifold from 2.38 lakh to 8.20 lakh between 2014-15 to 2019-20. There was an increasing trend in the number of activities for all years consecutively. In 2014-15, the highest number of work was for land development (85,762 works), followed by water conservation activities (35,298) and works related to road connectivity or internal roads and streets (32,308). In 2015-16, land development works remained at the top, while activities relating to road connectivity/internal roads came second, and works relating to water conservation third in terms of numbers. However, the scenario changed the next year. From 2016-17 onwards, the number of activities relating to water conservation was more than that relating to road connectivity; however, the highest number of work was for land development, as always. Apart from these three activities, the other important activities undertaken in Tripura in 2014-15 were related to irrigation, restoration of traditional waterbodies and afforestation. From 2015-16, activities relating to rural sanitation and improvement of land productivity also gained prominence. In 2016-17, apart from the earlier emphasized activities, watershed management and promotion of fisheries were also taken up in substantial numbers. Construction of houses and agriculture productivity were the newly encouraged activities of 2017-18, along with those initiated earlier. In 2018-19, irrigation and rural connectivity received additional focus with increased numbers, and the rise in the number of activities relating to these two types of work continued in 2019-20 too. The incremental change in absolute number of works taken up in 2019-20 was almost around 2.0 lakh, which by any standards is huge for a small state like Tripura. Apart from the above-stated activities, there were also other types of work taken up to meet specific local requirements, which accounted for around 20,000 activities every year.

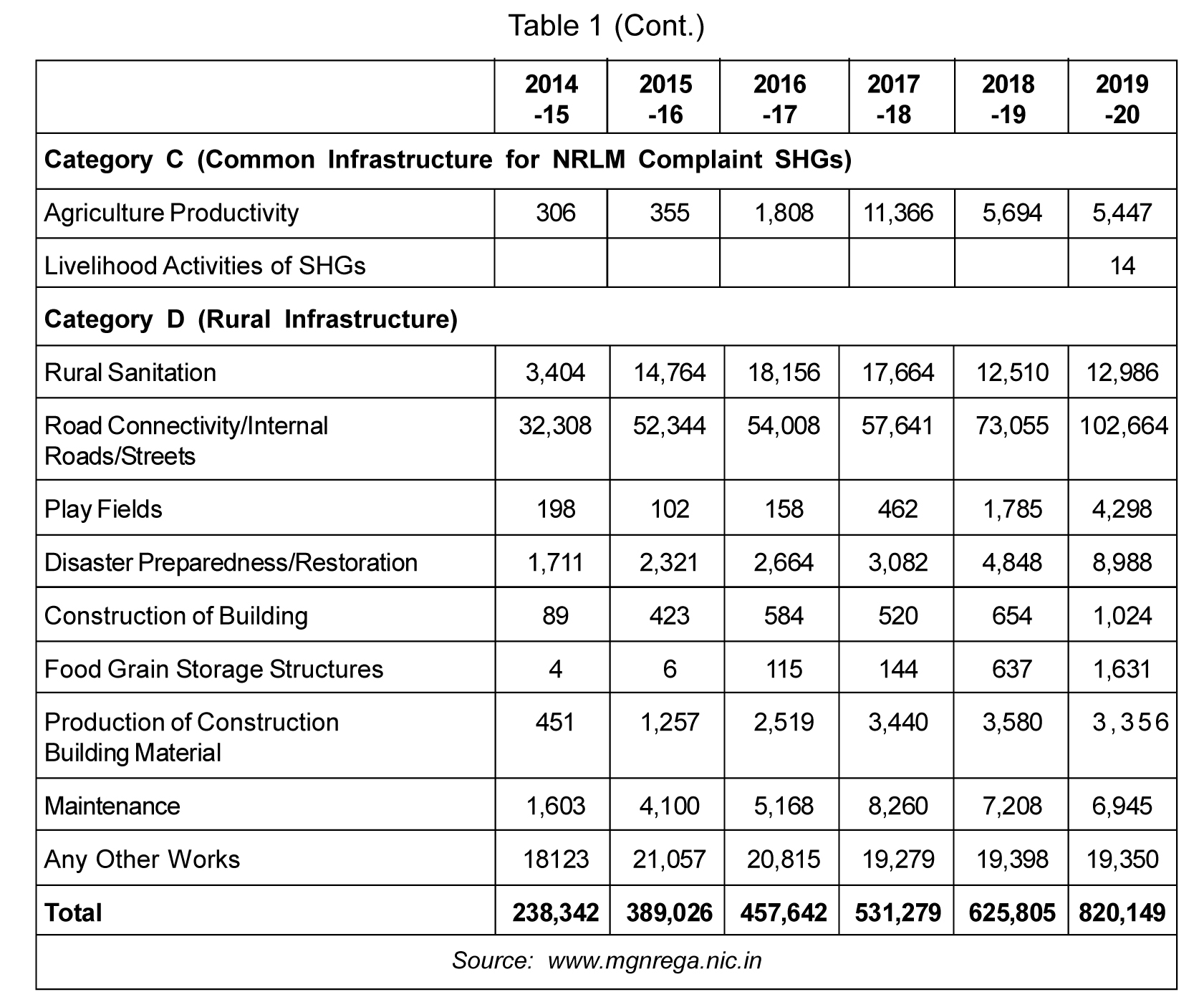

Figure 1 was constructed on the basis of Table 1. Here, the authors show the share of each four types of works with respect to total works. The shares of four types of works are categorized as A, B, C and D. From Figure 1, we can say that the four categories of work as identified by the authorities show that in Tripura activities relating to the first category A, i.e., public works relating to natural resource management, are the most prominent for all the years, accounting for almost 70% of all the works taken up. Category D, consisting of rural infrastructure activities, is the second most important type as rural connectivity and internal roads as well as rural sanitation come under this classification. Category B relates to the creation of individual assets for people belonging to the vulnerable sections. This kind of activity has been showing an increasing share over the years owing to increased number of works relating to improving land productivity for the past few years as well as more construction of rural houses particularly since 2016-17. Category C, comprising common infrastructure for National Rural Livelihood Mission (NRLM)-compliant self-help groups, has the smallest share in Tripura and accounts for around 1% of the total works.

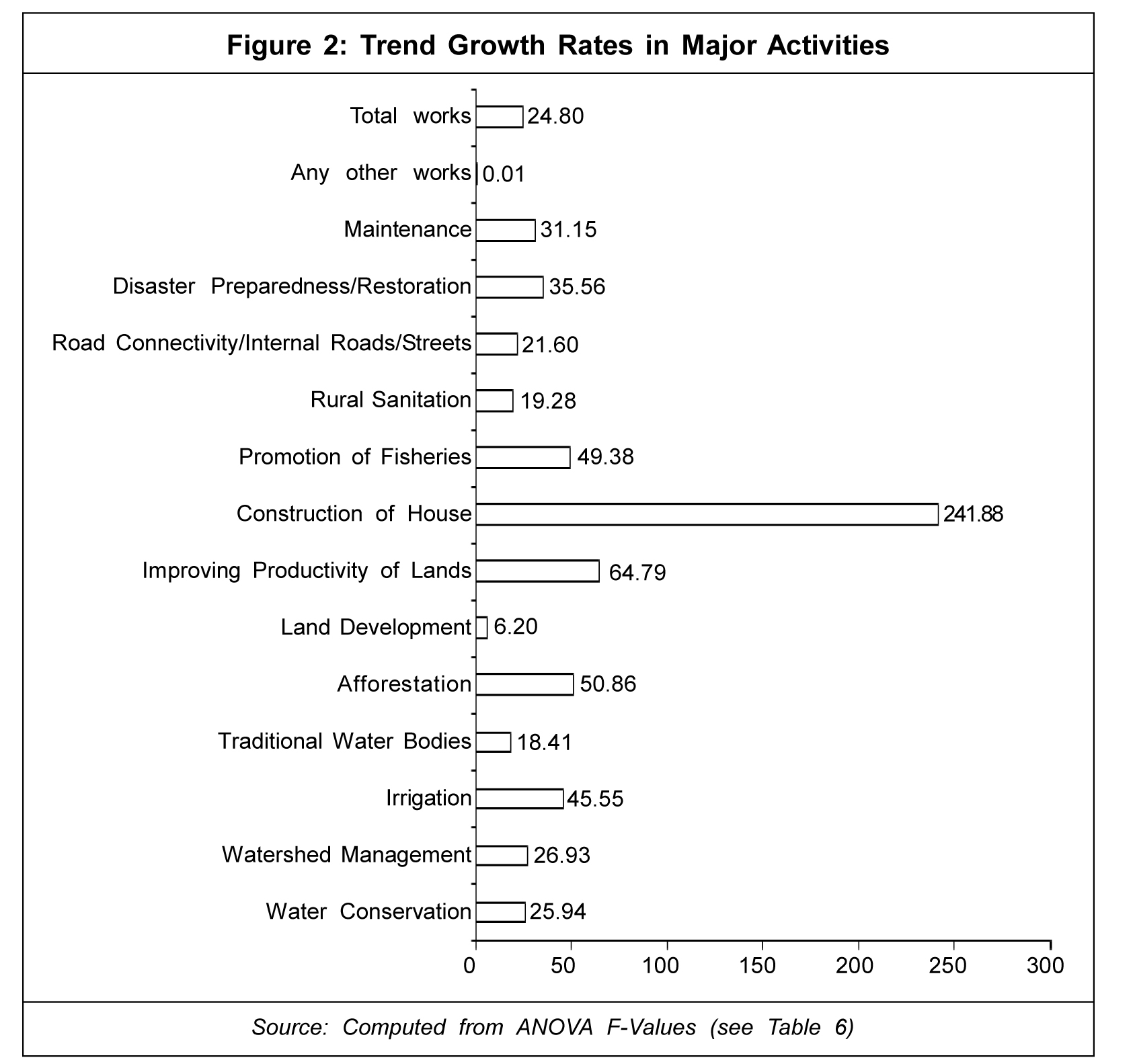

Figure 2 shows that construction of houses as an activity of MGNREGS in rural areas of Tripura has been growing at a stupendously fast rate (241.88%), owing to a major policy focus on overall development goals. Activities like promotion of fisheries, disaster preparedness, maintenance, improving productivity of lands, afforestation and irrigation have been growing at rates higher than the state aggregate rate (24.80%). Many of these works are oriented towards better management and utilization of natural resources. The interesting point here is that land development has a relatively slow growth rate, even though it has the largest share of activities. However, other types of works with a sizeable number of activities show negligible growth rate, suggesting increase in activities specified by guidelines.

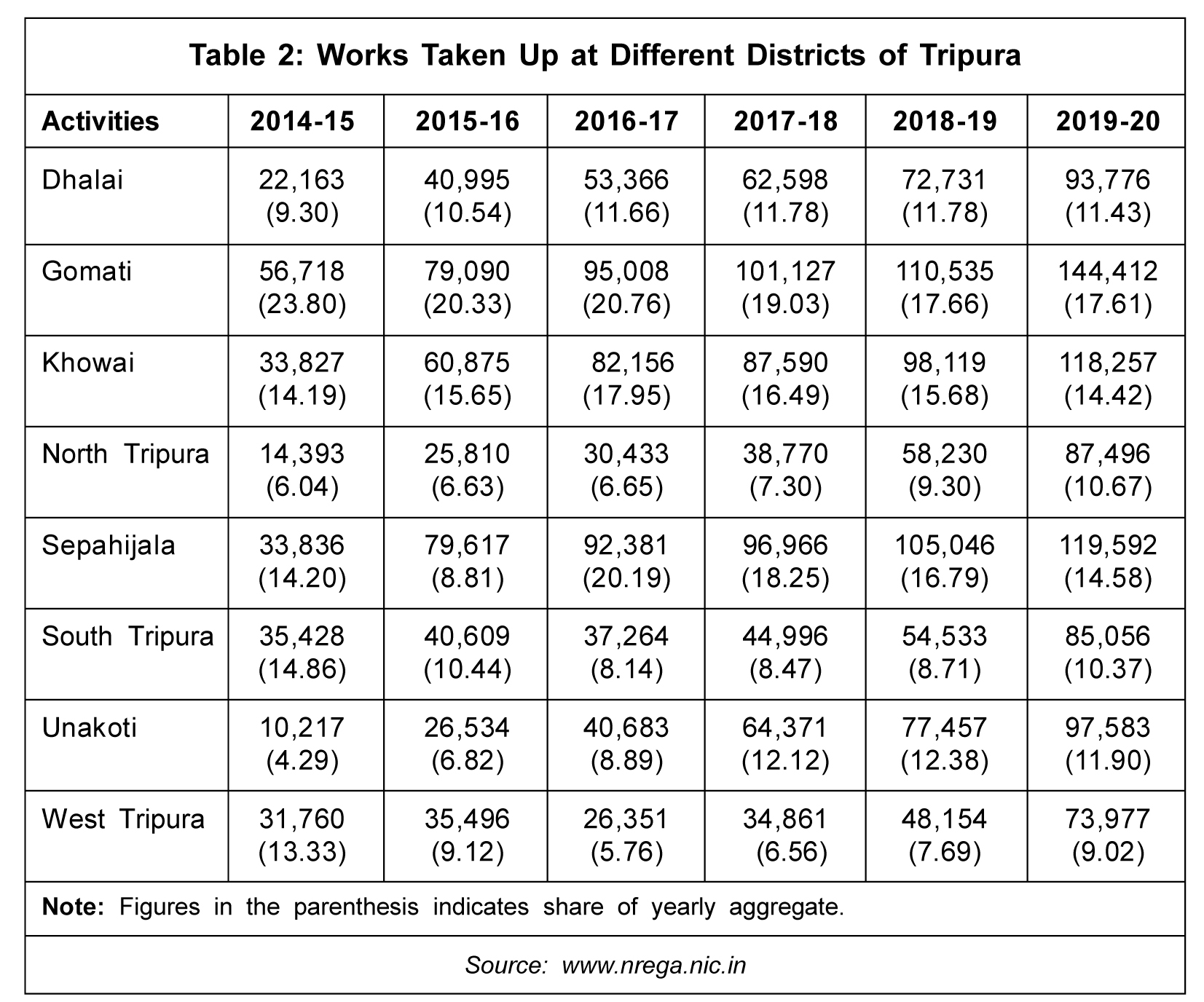

Table 2 shows that like the state aggregate, the number of activities or works increased for all the component districts over the years continuously, except for South Tripura and West Tripura districts, where the number of works undertaken decreased in 2016-17. Gomati district was the leader in terms of activities taken up in each year, but its share in the total work declined by almost 24% in 2014-15 to around 17.6% in 2019-20. On the contrary, the share of Unakoti district went up from 4.29% to 11.9% during the same period. Sepahijala and Khowai district also accounted for almost 15% of the total works each, followed by Dhalai, North Tripura and South Tripura. The share of West Tripura in total works undertaken has come down from above 13% to 9% in these six years.

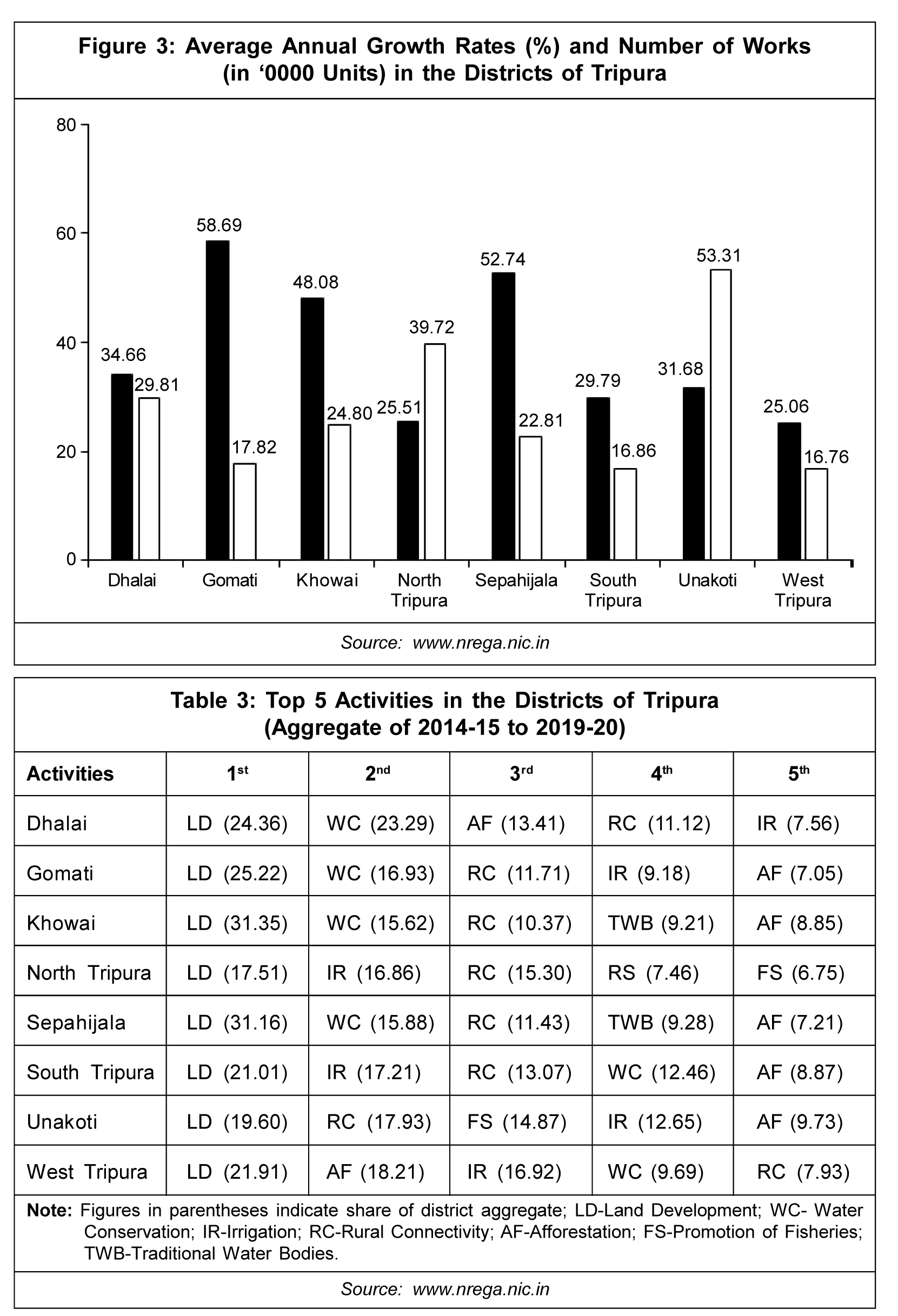

Figure 3 shows that over the years, the largest number more than 580,000 of activities was held in Gomati district, while the aggregate number around 250,000 of works was lowest in West Tripura district. Sepahijala and Khowai were placed second and third, respectively, in terms of work undertaken during these six years. The annual average growth rate for works taken up was very high in Unakoti district, which was the reason for its increased share in the total aggregate of works. The Average annual growth rate (AAGR) for North Tripura was also high. The least rate was again for West Tripura district.

From Table 3, it is seen that land development activities were the most prominent work taken up in all the districts. Water conservation activities were found to be the second most important in four of the eight districts, while it was also among the top 5 activities in two more districts. Irrigation work secured the second rank in two districts, namely, North Tripura and South Tripura, while rural connectivity and afforestation were the second most prominent work in Unakoti and West Tripura districts. Rural connectivity was the third most important activity in five districts, whereas it was the fourth and fifth most important work in Dhalai and West Tripura districts. Afforestation was the third-most important work in Dhalai district, while promotion of fisheries and irrigation held the third position in Unakoti and West Tripura respectively. Restoration and management of traditional water bodies was the fourth most important activity in Khowai and North Tripura district. Rural sanitation occupied the fourth position in North Tripura. Afforestation was the fifth most important activity in five districts. Thus, we find from Table 3 that the kind of activity taken up in the districts indicates a similar trend with occasional variations. Most of the works taken up are related to management of natural resources, while aspects of rural infrastructure, particularly in terms of rural connectivity and internal roads, also get some importance. Individual asset building for vulnerable sections was also focused on in some of the districts.

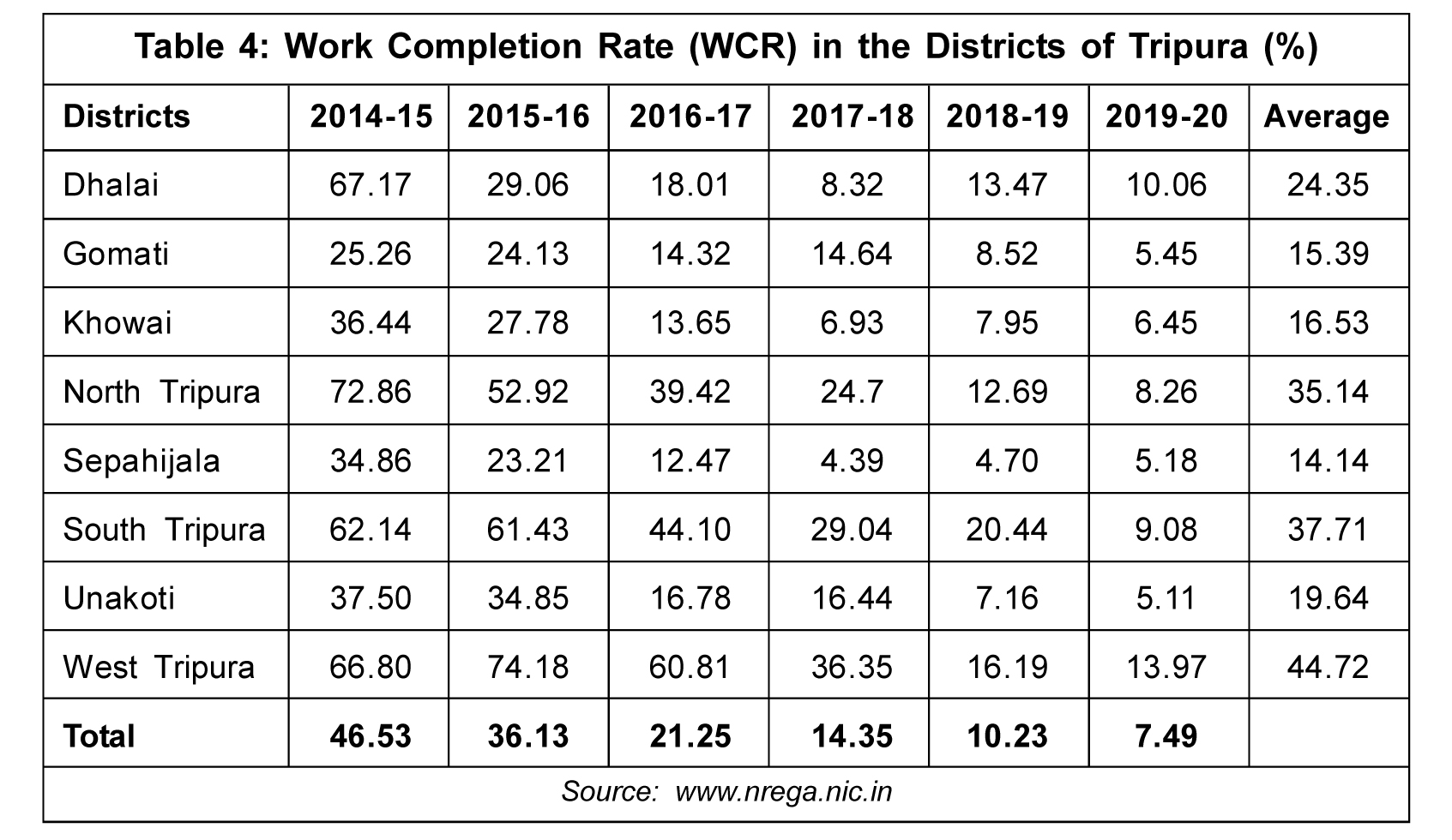

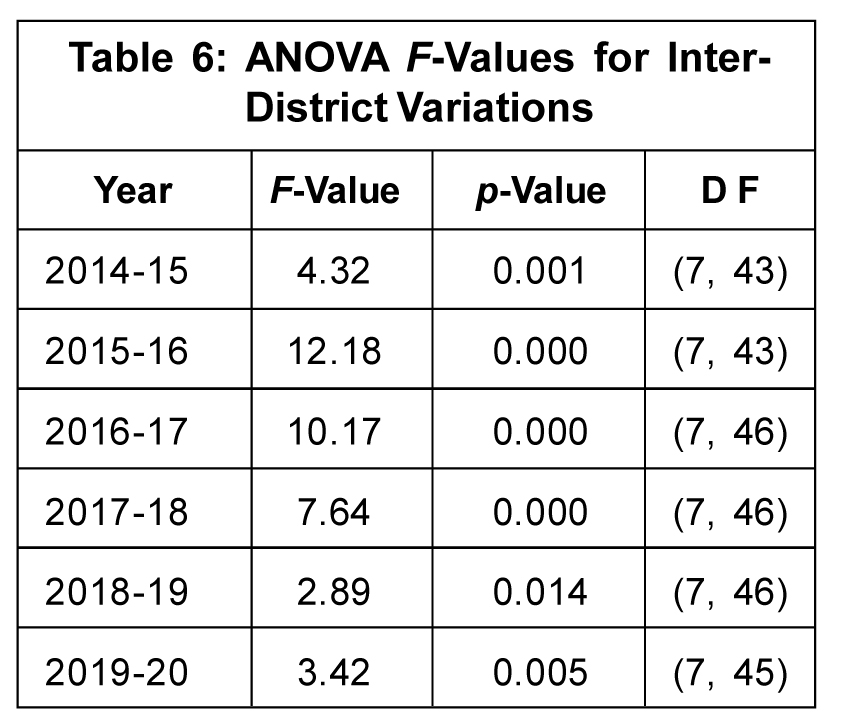

Taking up work in itself is not the end; it is more important to examine whether the activities taken up get completed or not. This is particularly important because it has often been said that MGNREGS has made immense contribution in terms of employment generation, however, the aspect of the second objective leaves a lot of scope for improvement. Table 4 shows that the work completion rate (WCR) in the districts of Tripura varied from a high of 74.18% in 2015-16 to 4.39% of 2017-18 at Sepahijala. The yearly WCR for the state came down from 46.53% in 2014-15 to 7.49% in 2019-20. The average of the districts over the six year period was found to be highest in West Tripura (44.72%) and least (14.14%) in Sepahijala. West Tripura had the highest WCR for four of the six years under consideration, while North Tripura and South Tripura led in 2014-15 and 2018-19 respectively. On the other hand, apart from Unakoti in 2019-20, WCR was lowest in Sepahijala for all the other five years.

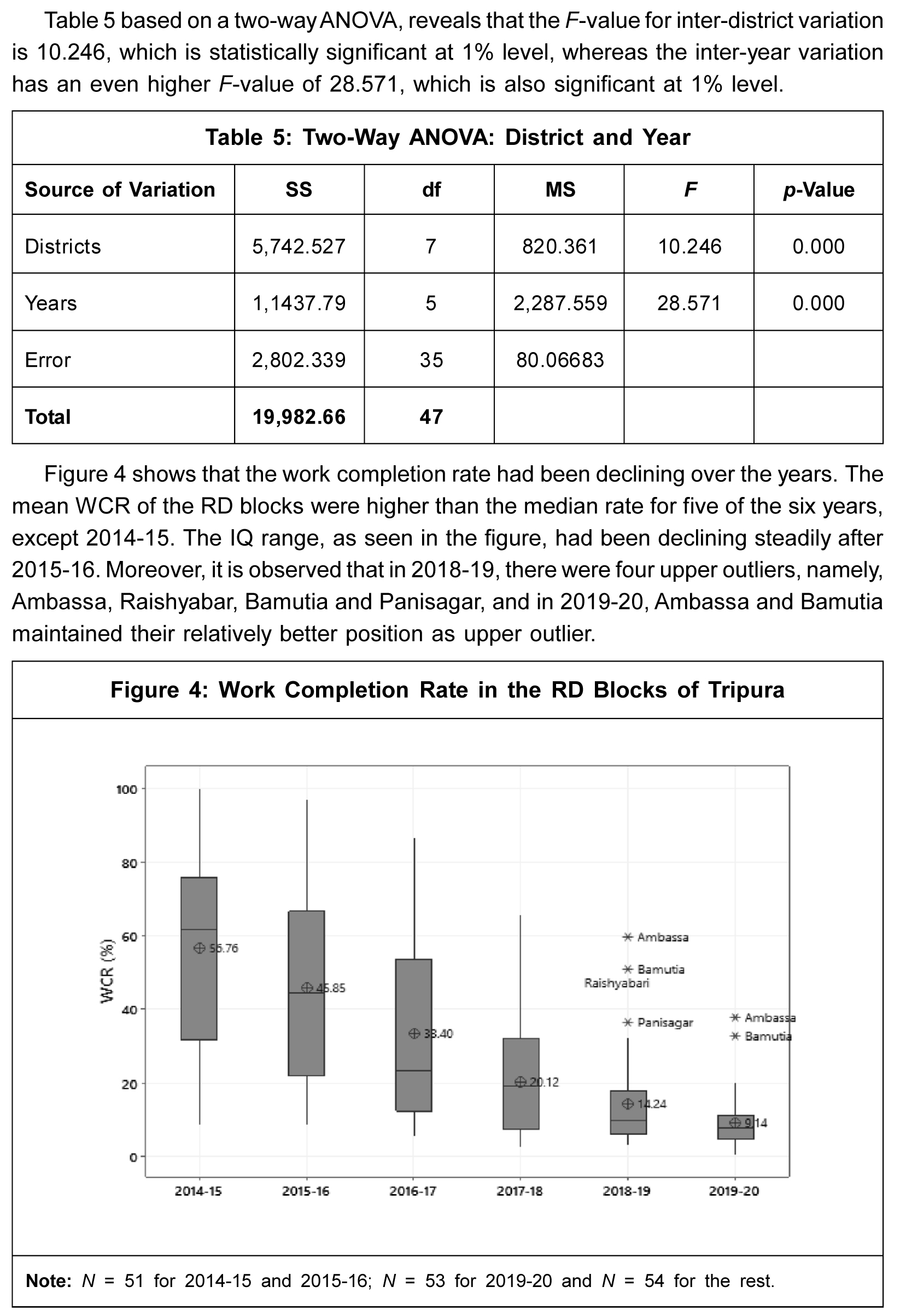

Table 5 based on a two-way ANOVA, reveals that the F-value for inter-district variation is 10.246, which is statistically significant at 1% level, whereas the inter-year variation has an even higher F-value of 28.571, which is also significant at 1% level.

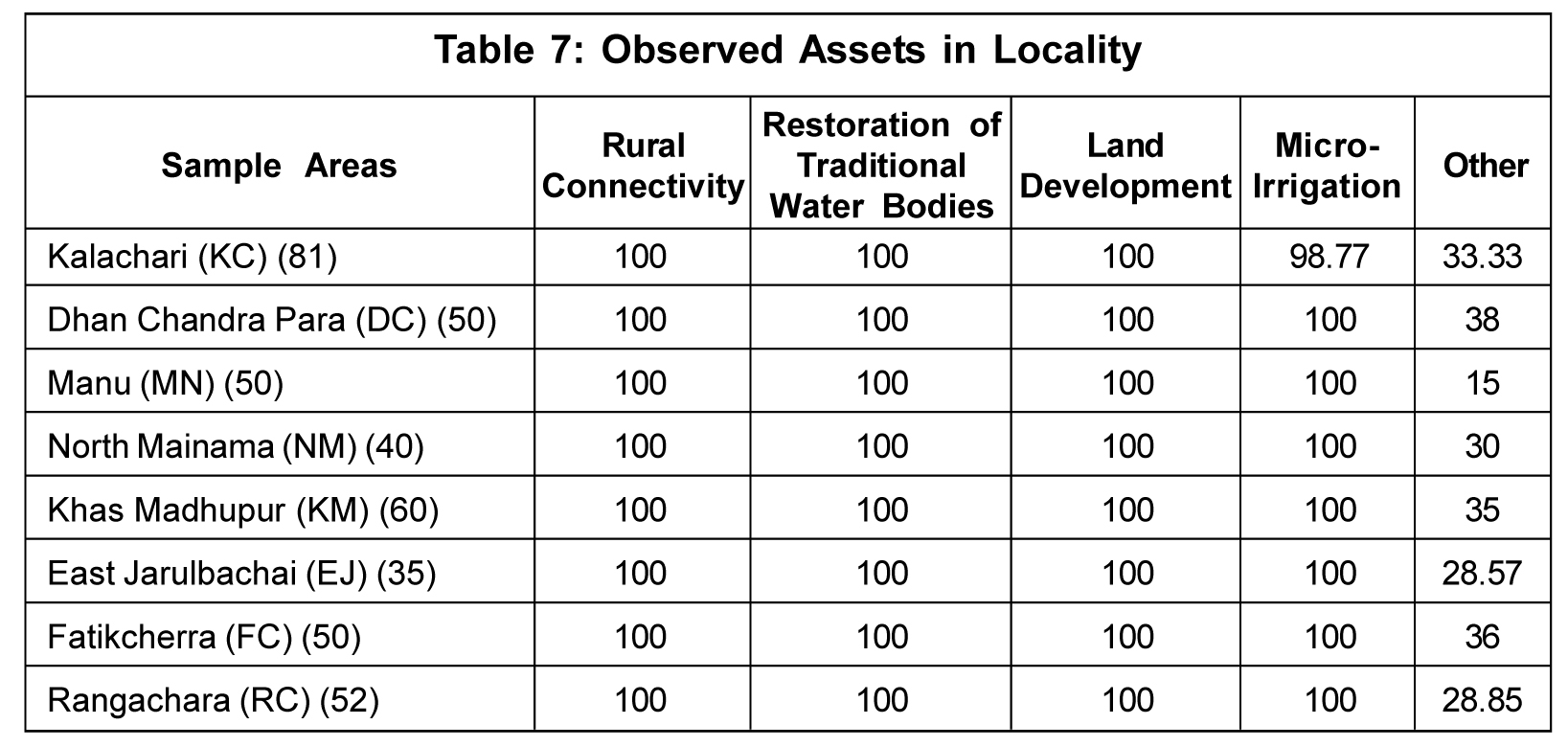

The F-values in Table 6 indicate statistically significant inter-district variation in the average WCR for all the years considered. In 2018-19, the mean difference was significant at 5% level, while for all the other years, the difference was significant at 1% level. The substantial variation in WCR across the RD blocks of the state therefore raises an opportunity for further exploration.

Asset creation has been the second objective of the scheme along with employment generation. The creation of rural assets has twofold outcome - firstly, in the current period, it acts as a source of employment in the course of being created, and secondly, in the future, it acts as a resource to foster economic activity. Thus, the second objective of the study was to analyze the benefits accruing to the rural participants from the assets created. In this context, it may be noted that the scheme mandated creation of public assets primarily, but works for creation of certain private assets were also provisioned. We mainly consider the public assets and examine the benefits, quality and importance of such assets. A small note on the types of private assets created is also provided. However, the analysis is made completely on the information shared by the participating households and is based on their perceptions.

Types of Asset

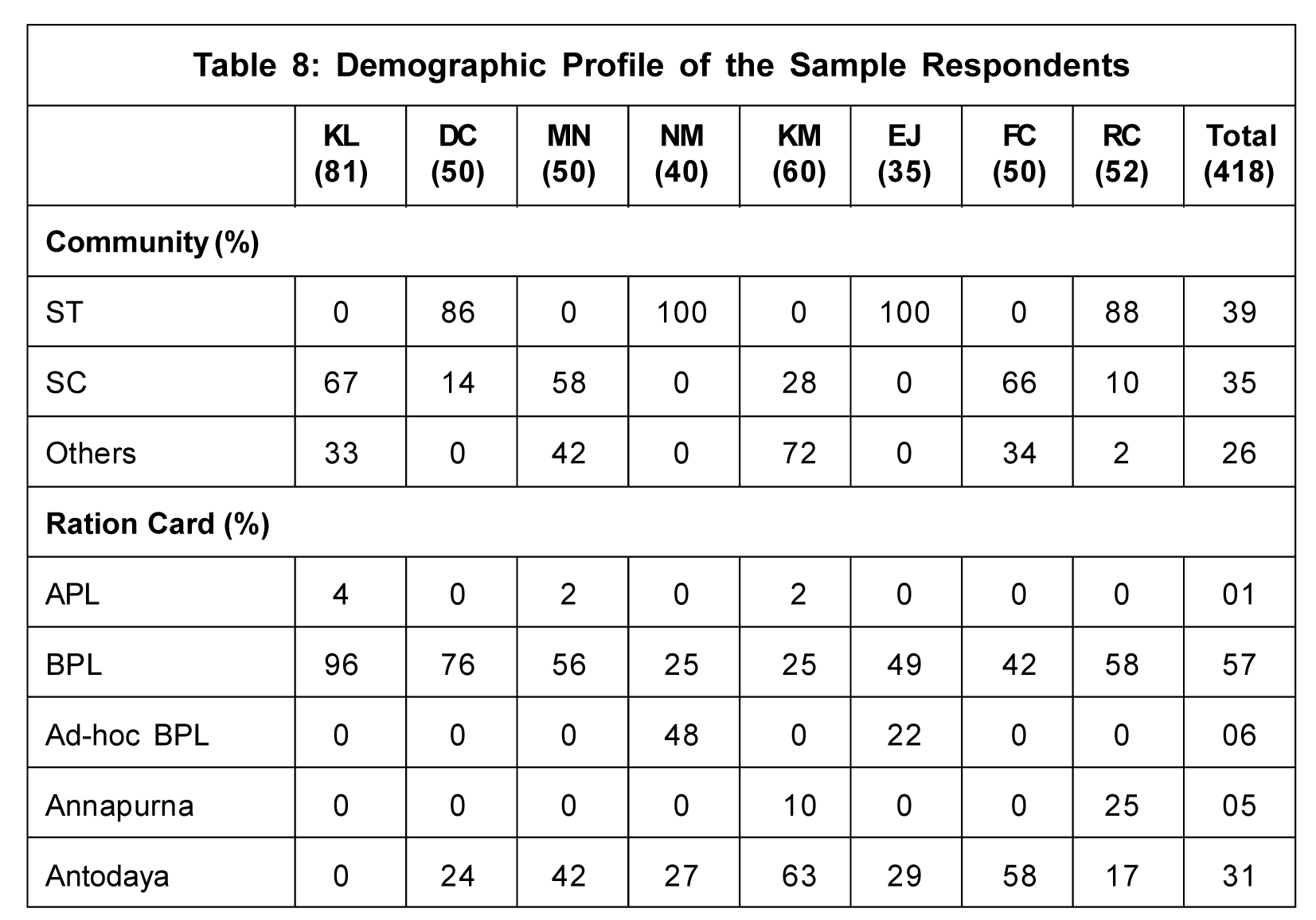

Table 7 records the types of assets created in the sample village. It is interesting to note that assets related to rural connectivity, restoration of traditional water bodies, and land development have been created and noticed and recorded by all the respondents from all the right representative GPs considered in the present study. However, except one respondent from Kalachari GP, all the remaining 417 respondents from participating households were for creation of assets related to micro-irrigation. Interestingly, 137 respondents spread across the eight GPs observed other type of assets like provision of irrigation facilities, water harvesting, flood management, drought proofing, etc. Other types of asset were reported by 38% of respondents from Dhan Chandra Para, while such responses were least among the respondents of Manu (15%).

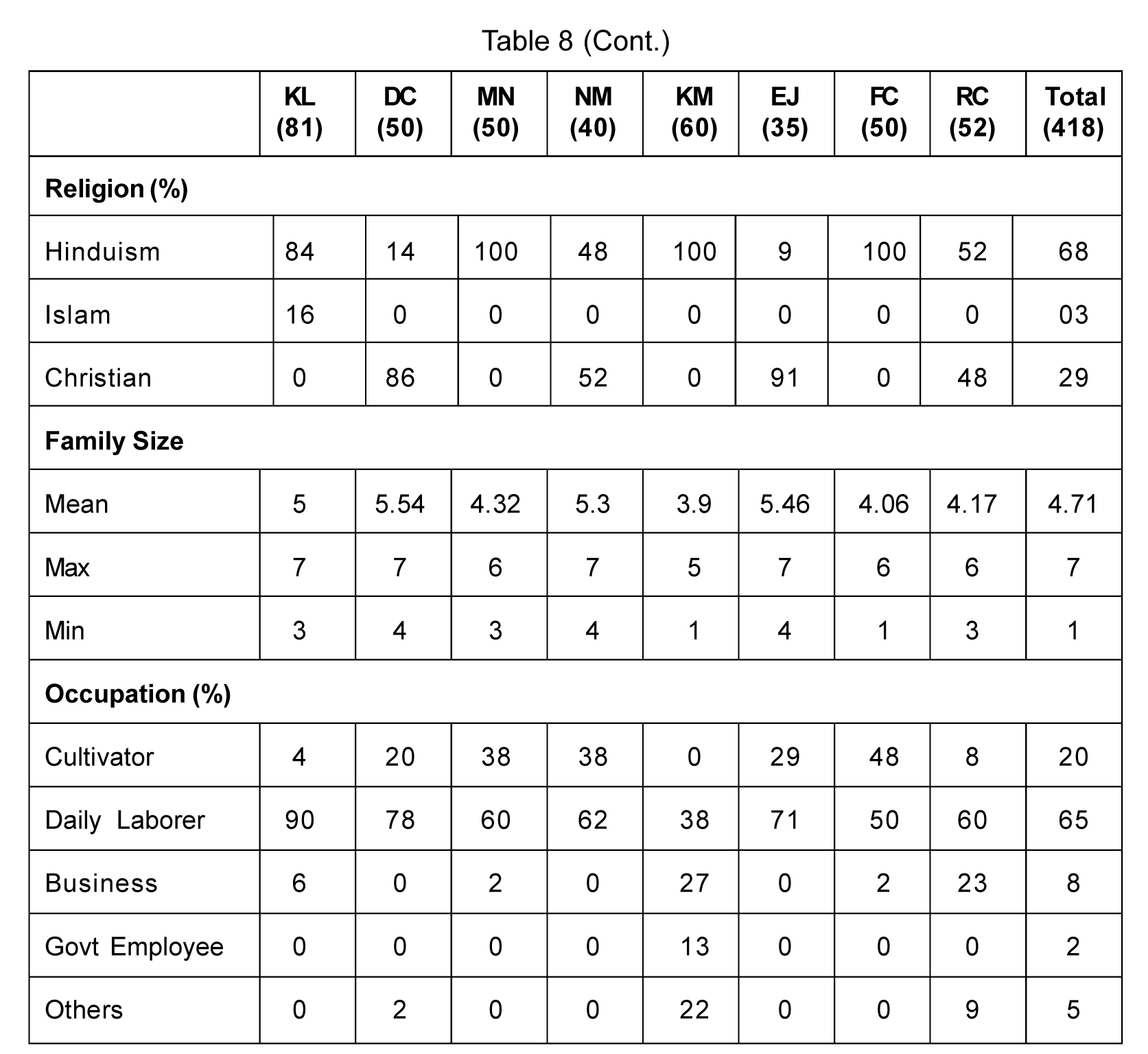

Table 8 indicates that among the participating households, most of the respondents belonged to socially excluded group (39% ST and 35% SC) and were from the marginal sections of the society. Four GPs, namely, Dhan Chandra Para, North Mainama, East Jarulbachai and Rangachara were ST majority, while in Kalachari, Manu and Fatikcherra, SCs were prominent. Others were in majority only in Khas Madhupur. GP of West Tripura district. Moreover, proportion of BPL card holders among the participating household was found to be 57%, followed by 31% of Antodaya. Participants from Kalachari were overwhelmingly BPL, while a majority from Dhan Chandra Para, Manu, East Jarulbachai, and Rangachara were also BPL card holders. Antodaya card holders were maximum in Khas Madhupur and Fatikcherra. APL card holders were negligible. Hinduism is the dominant religion (68%) among the participating households, while a moderate proportion of sample respondents (29%) in tribal majority GPs, namely Dhan Chandra Para, North Mainama and East Jarulbachai, followed Christianity. Further, we observed that there are also a few practitioners of Islam in Kalachari.

Beneficial Assets

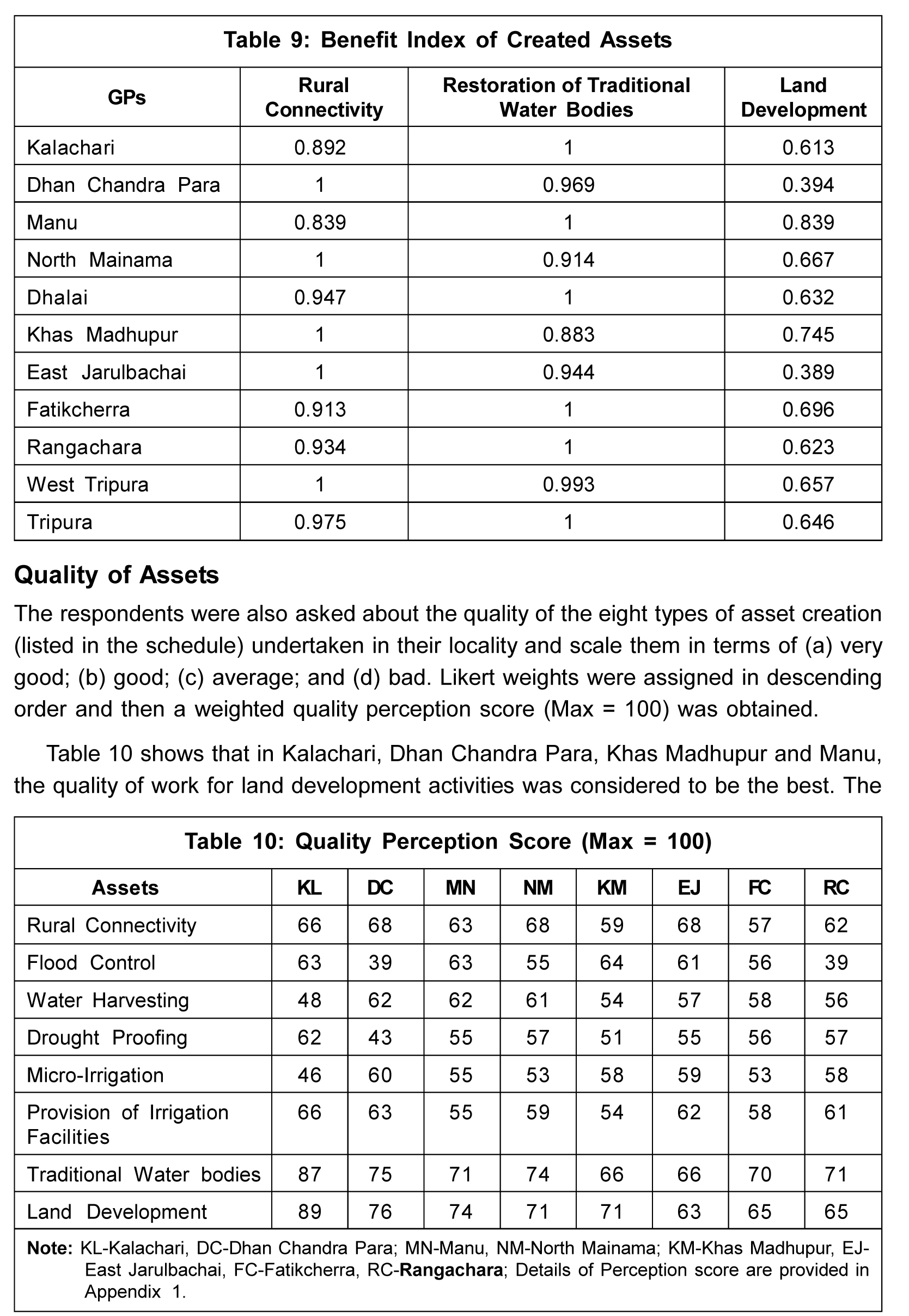

The respondents were asked to rank the three most beneficial works undertaken in their locality under MGNREGS. The ranks of the respondents were accorded Likert weights in decreasing order of preference, and a benefit index was constructed to estimate the aggregate trend, with the most beneficial being accorded an index score of 1. It is interesting to note that all the respondents mentioned the three activities of asset creation for rural connectivity (RC), land development (LD) and restoration of traditional water bodies (WB) as the three most beneficial ones, albeit in different order. Table 9 shows the different types of work which are most beneficial, and accordingly an index has been constructed. The ranks of the respondents were accorded Likert weights in decreasing order of preference, and a benefit index was constructed to estimate the aggregate trend with the most beneficial being accorded an index score of 1. On this basis, we have the score of each of the eight GPs. Moreover, the score of Dhalai is calculated on the basis of average of four GPs constituted under this district. Similarly, we have calculated the score for West Tripura and Tripura as a whole.

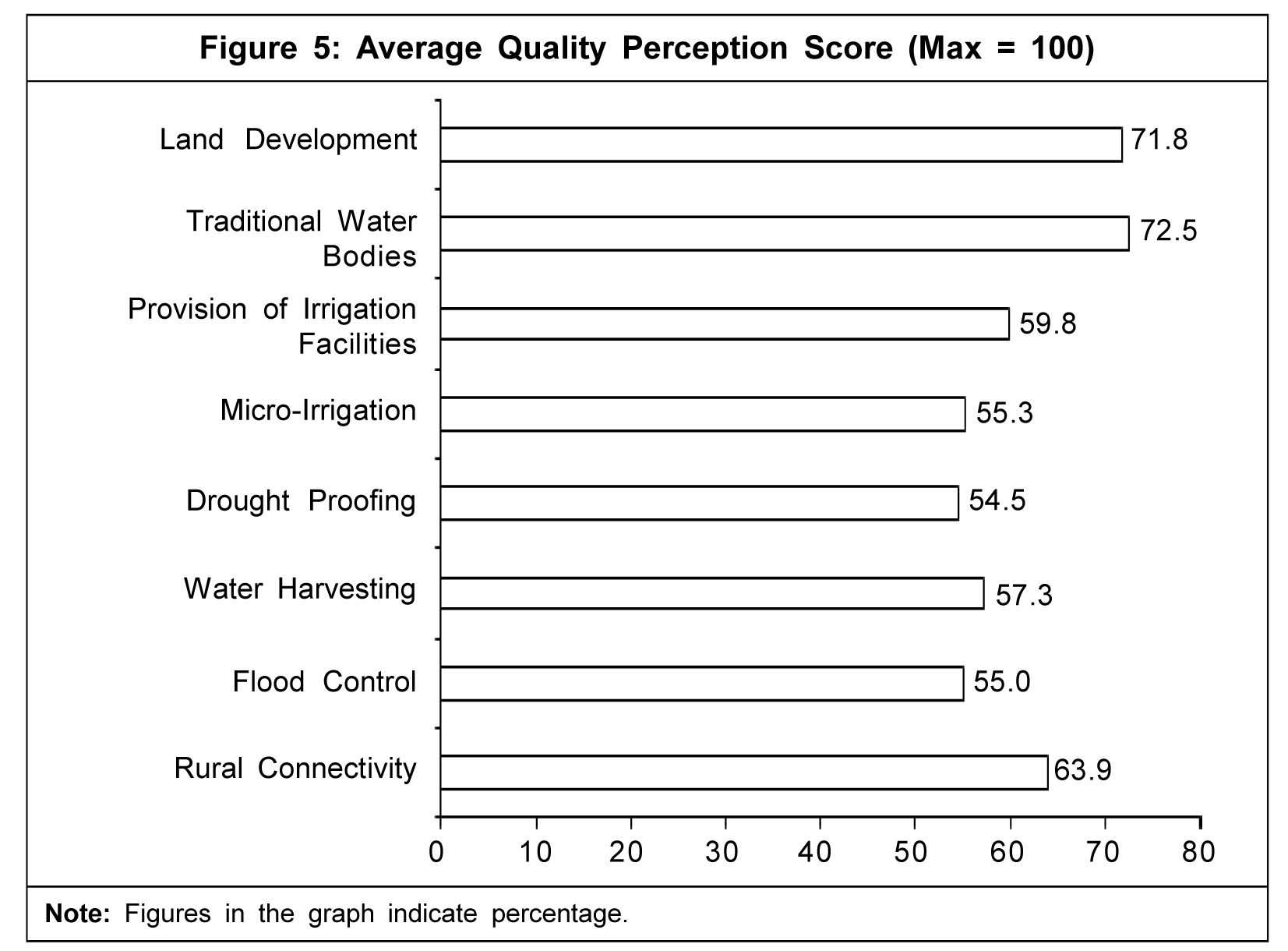

perception of better quality in East Jarulbachai was highest for rural connectivity. The respondents of North Mainama, Fatikcherra and Rangachara perceived the quality of restoration of traditional water bodies as the topmost. Among the listed activities, the perception score for flood control works was below 40 in Dhan Chandra Para and Rangachara, indicating poorer quality. Drought proofing in Dhan Chandra Para and water harvesting and micro-irrigation in Kalachari were been perceived to be less than 50, which certainly does not speak impressively about the quality. On the other hand, the respondents of the same Kalachari accorded high scores (almost 90) for work related to land development and water bodies, which is indicative of better quality. Scores for these two activities were above 70 in several other GPs too.

From Figure 5, we can see that the average perception score regarding quality was highest for activities relating to restoration of water bodies (72.5), followed closely by land development (71.8). Rural connectivity with a score of 63.9 was found to be third in rank in terms of quality of work. The other types of asset creating activities had much lower quality perceptions among the respondents. Provision of irrigation facilities had a combined average score of almost 60, while water harvesting was around 58. The other three types of activities-flood control, drought proofing and micro-irrigation-suggest a score of around 55, which does not speak very strongly about the quality of asset creation. It may be noted here that quality aspect of assets has always been an issue in the implementation of the scheme, and we did not find much exception here.

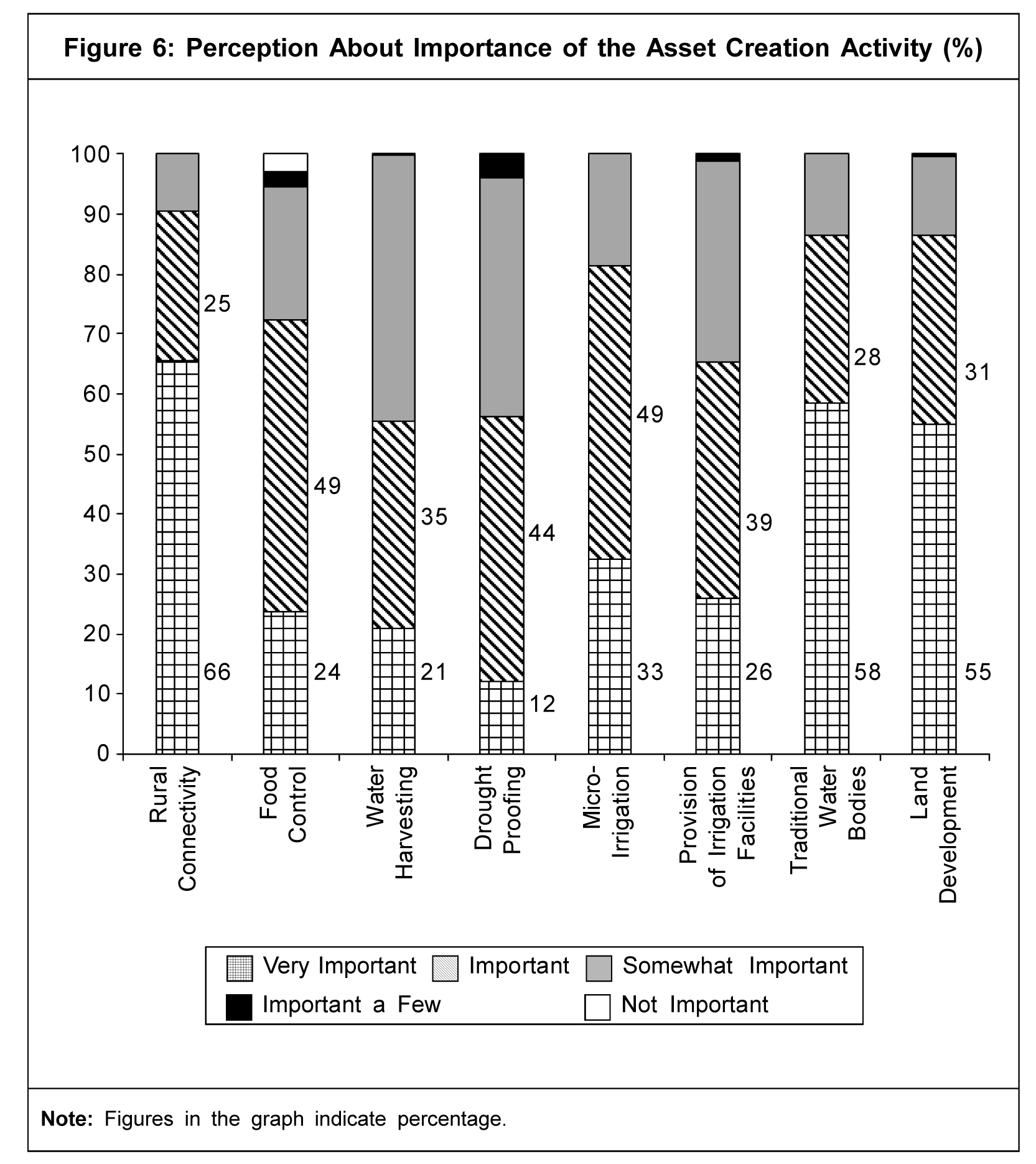

Importance of the Asset

As far as perception of quality is concerned, the respondents were further queried about the importance of the asset creation activity undertaken in their locality. The same eight type of activities were identified and the respondents were asked to mark them as:

(a) very important; (b) important; (c) somewhat important; (d) important to a few; and

(d) not important on the basis of its potential to contribute to the economic life and livelihood of the residents of the village. On improving the asset base of their locality and using a 5-point Likert scale, we obtained a perception score of Importance (Max = 100) for each activity corresponding to each GP.

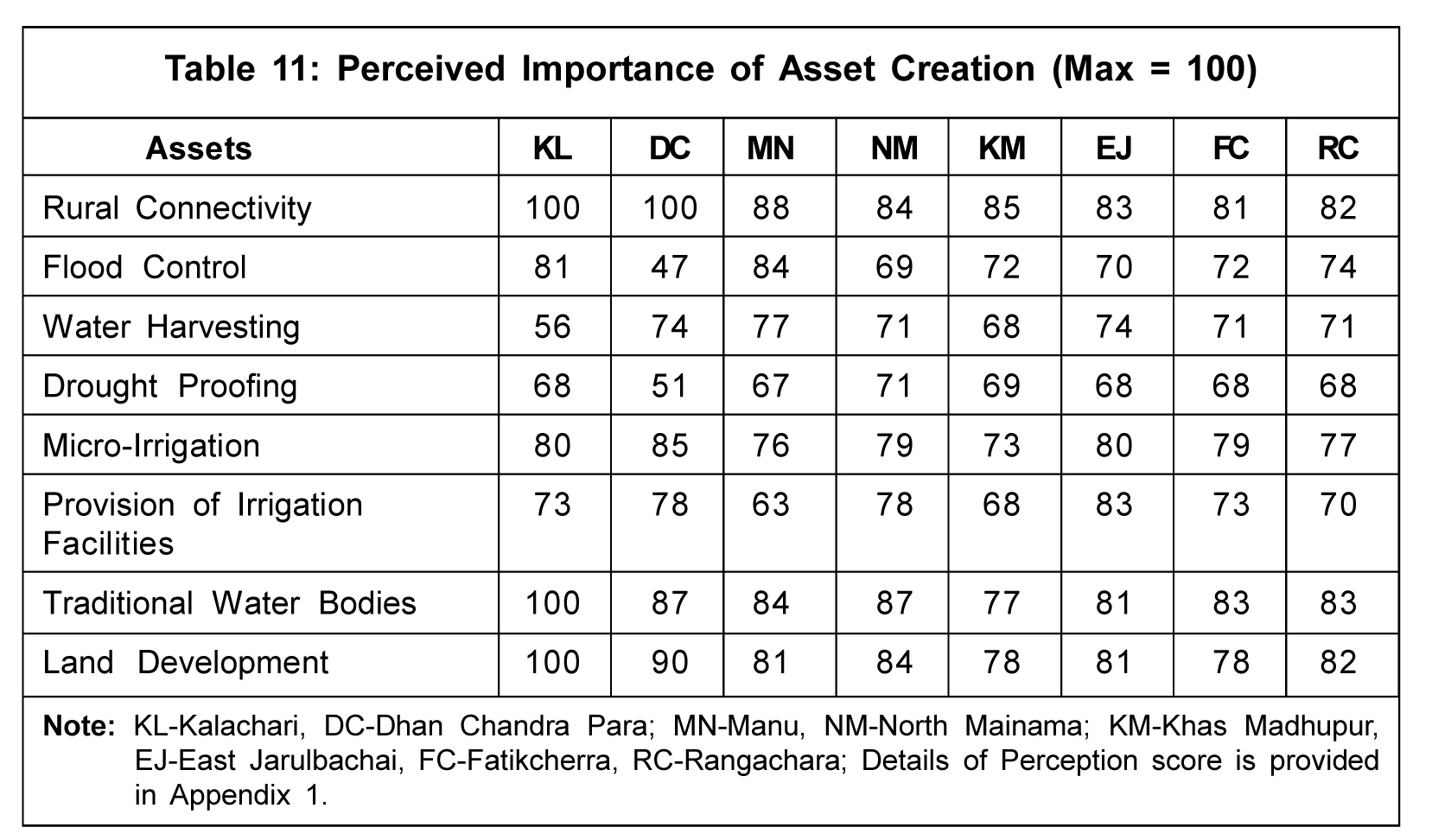

Table 11 shows that rural connectivity works were perceived to be very important in almost all the GPs with residents of Kalachari and Dhan Chandra Para according it the maximum possible relevance. Better roads and connectivity had several positive multiplier effects on the quality of life and livelihood efforts. Flood control as an activity was quite important in most of the GPs, except DC Para, where drought proofing also had limited importance . Water harvesting was less important in Kalachari as compared to other GPs. Micro-irrigation was substantially important in all GPs, mostly because it helped in boosting the productivity of the primary sector of the rural areas. Support for provisioning of irrigational facilities, restoration of water bodies and land development activities in the locality also received a big support from a majority of the respondents for the same reason. Support for the last two types of asset creation in Kalachari was at the zenith, whereas East Jarulbachai scored the maximum for the first work. Restoration of traditional water bodies obtained the highest score in the three GPs of North Mainama, Fatikcherra and Rangachara . Rural connectivity had the highest score in Manu, Khas Madhupur and East Jarulbachai.

Figure 6 shows that across the state, the relative importance of rural connectivity works was highest followed by restoration of traditional water bodies and land development. Construction of internal roads, streets and road connectivity in remote parts certainly added a lot to the quality of life of remote dwellers and hence the emphasis on its extreme importance, particularly from the respondents of the most backward district of Dhalai. Micro-irrigation was also important to many, while flood control and provision for irrigation had somewhat lesser relevance. However, the relative importance of water harvesting and drought proofing was much lower. Interesting to note here was that among the various types of work, only flood control had been marked as not important by a few respondents.

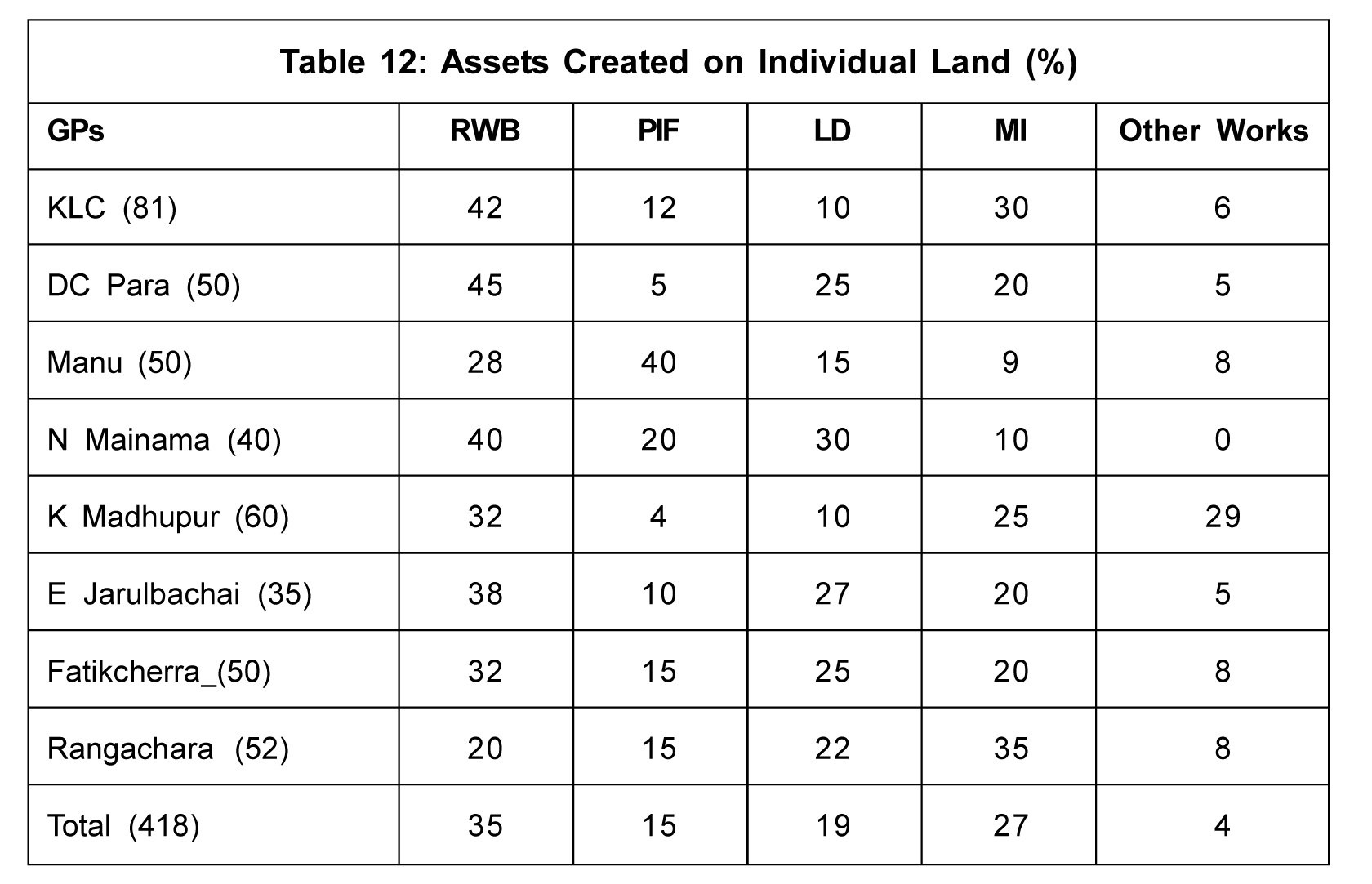

Private Assets

Table 12 shows the assets created on individual lands of the beneficiaries or participants. All the GPs reported such activities on private properties. We found that in aggregate 35% of such asset creation was related to rural water bodies (RWB), while 27% works were related to Micro-Irrigation (MI). 19% of the works were on land development (LD) and 15% works were for provisioning of irrigation facility (PIF). RWB was the most prominent work across all villages, except Manu and Rangachara, PIF and MI were the leading activities in these two GPs respectively. Other types of works accounted for the remaining 6%. One interesting thing to be noted here is that that more than 75% of the assets created belonged to water resources. Creation of water-based resources and assets can be considered as an orientation towards more primary sector activities, particularly increasing cropping intensity as well as diversified livelihood through aquaculture and fishery in the sample GPs.

Conclusion

The study examined the aspects of asset creation and the nature and trend of activities at the block level in Tripura. The study found that the number of activities taken up under the MGNREGS scheme had increased by more than threefold in the six-year period. The growth rate of the number of activities was 24.8%. Land development, irrigation and water conservation remained the most prominent of works, thereby creating an overwhelming dominance of activities earmarked as public works relating to natural resources management in the state. Creation of rural infrastructure, particularly building of rural roads and internal streets, was a premier activity. Construction of rural housing, afforestation, improving land productivity, fisheries, watershed management, disaster preparedness were the other important activities in Tripura taken up as MGNREGS works. Gomati led among the districts in terms of number of works, followed by Sepahijala.

However, the increase in the number of works taken up does not ensure thorough outcome as the work completion rate for the state seems to show a steep downward slope. The WCR was around 44% in 2014-15, but came down to 7.49% in 2019-20, suggesting strong and significant inter-year differences in the average WCR. The study also found statistically significant inter-district variations using the work completion rate (WCR) of constituent RD blocks to calculate the district WCR. The declining completion rate is certainly a major concern regarding the implementation of MGNREGS in Tripura. The geo-tagging of asset creation and the changed structure of volume of work-based payment is said to be contributing to the reduced dominance of MGNREGS in the rural economy of Tripura, which has seen significant cash flow and generation of demand during the first decade of the scheme.

The other aspect of asset creation, i.e., benefits accruing to the participating households from the assets created, is the second objective of the study. Here, we found that the most common types of asset creation in the rural areas of the GPs, as viewed by the respondents, were related to rural connectivity, restoration of traditional water-bodies and land development works. Activities relating to micro-irrigation were also very commonly seen. Activities related to internal roads, streets, village connectivity were most beneficial to some of the villages, while for the rest, the benefits mostly accrued through water bodies. The quality of the executed works or assets created varied from village to village; however, the respondents perceived that works on land development, water bodies and rural connectivity were better than the rest. Similarly, these three types of activities and the associated assets created were also ranked high in terms of importance, as these were more effective in providing further productive and economic linkages. Nonetheless, all the activities listed were related to better utilization of local resources and expected to be the harbinger for future development and economic initiatives. Interestingly, a majority of private works undertaken through the scheme were related to restoration or generation of water resources.

To sum up, it can be said that the assets created under the scheme facilitated greater primary sector activities in the local area. Moreover, assets created for connectivity provided better market linkage, which had a multiplier effect on the livelihood efforts of the participating households. In a nutshell, one can say that the impact of MGNREGS on the households has been substantially positive, particularly because alternative gainful employment and income opportunity in the rural and remote areas of Tripura are extremely limited. Opportunities through MGNREGS have boosted the effective demand of the participating households, which has its linkage in the local and regional market.

Limitations and Future Scope: The present study used secondary data from 2019 to 2020. However, if it could be extended up to 2022-23, analysis and conclusion part would be more meaningful. Moreover, in the present study, only two districts of the state were considered, which is also a limitation of the study.

Asset creation under MGNREGS for Tripura was examined, and based on the findings, it can be said that there has been a delay in the completion of works under the scheme and inspection of the projects has been irregular. Therefore, respective gram panchayats may give more emphasis to work completion. Also, there is an issue of quality of work and asset creation under MGNREGS. Literature also suggests that the quality of asset under the scheme is questionable, which may also be given more focus by the implementing authority. The wage rate under MGNREGS may be increased so that the beneficiaries will be attracted to work under the scheme, and as a result, the quality of work may also improve. The wage distribution system may be streamlined by the competent authority so that the beneficiaries are at an advantage.

References

- Aggarwal Ankita and Vipul Kumar Paikra (2020), "Why MNREGA Wages are So Low", The Print, October 12, 2020.

- Arora Vinitha, Kulshreshtha L R and Upadhyay V (2013), "Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme: A Unique Scheme for Indian Rural Women", International Journal of Economic Practices and Theories, Vol. 3, No. 2, pp. 37-53.

- Banerjee Hema (2009), "MGNREGA: A Study in Andaman and Nicobar Islands", Kurukshetra, Vol. 56, No. 3, pp. 25-31.

- Banerjee Kaustav and Partha Saha (2010), "The NREGA, the Maoists and the Developmental Woes of the Indian State", Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 46, No. 28, pp. 42-48.

- Centre for Research in Rural and Industrial Development (2009), "Appraisal/Impact Assessment of NREGS in Selected Districts of Himachal Pradesh, Punjab and Haryana", Report submitted to the Ministry of Rural Development, Sponsored by UNDP.

- Centre for Rural Development (2010), "National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA): Some Field Reports", Report Submitted to Ministry of Rural Development, Government of India, New Delhi.

- Cook, Justin and Manisha Shah (2020), "Examining the Macro Effects of MNREGA", Ideas for India. https://www.ideasforindia.in/topics/poverty-inequality/examining-the-macro-effects-of-mnrega.html

- Deininger Klaus and Yanyan Liu (2010), "Welfare and Poverty Impacts of India's National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme: Evidence from Andhra Pradesh", Public Policy & Regulation e Journal. doi:10.1596/1813-9450-6543

- Dreze J and Reetika Khera (2009), "The Battle for Employment Guarantee", Frontline, Vol. 26, No. 1, pp. 4-26. Retrieved from http://info.worldbank.org/etools/docs/library/245844/Public%20workd_

- Imbert, Clement, and John Papp (2011), "Estimating Leakages in India's Employment Guarantee", in Reetika Khera (Ed.), Battle for Employment Guarantee, pp. 269-278, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Indian Institute of Forest Management (2010), "Impact Assessment of NREGA's Activities for Ecological and Economic Security", Sponsored by UNDP, New Delhi, http://iifm.ac.in/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/20124.pdf

- Institute of Rural Management Anand (2010), "An Impact Assessment Study of the Usefulness and Sustainability of the Assets Created under Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) in Sikkim", Report submitted to Rural Management and Development Department, Government of Sikkim. https://nrega. nic.in/netnrega/success%20stories/IRMA_Study_Sikkim_2010.pdf

- Jain Pradeep and Raminder Jit Singh (2013), "Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) on the Touchstone of Social Security", Indian Journal of Applied Research, Vol. 3, No. 2. doi: 10.36106/ijar

- Jeyaranjan J and Vijayabaskar M (2009), "Is NREGA Denying Labor Access to Manufacturing? Evidence from Tamil Nadu". http://www.socialprotectionasia.org/conference1/jeyaranjan.pdf

- Jha R, Gaiha R and Pandey M K (2010), "Net Transfer Benefits Under India's Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme", Journal of Policy Modeling, Vol. 34, No. 2, pp. 296-311, ISSN: 0161-8938.

- Kareemulla K, Srinivas Reddy K, Ramarao C A and Shalander Kumar (2009), "Soil and Water Conservation Works through National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (NREGS) in Andhra Pradesh: An Analysis of Livelihood Impact", Agricultural Economics Research Review, Vol. 22, Conference Paper, pp. 443-450.

- Kulkarni Ashwini, Ranaware K, Narayanan S and Das U (2015), "MGNREGA Works and Their Impacts: A Study of Maharashtra", Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 50, No. 13, pp. 17-35.

- Kumara, Praduman and P K Joshi (2013), "Household Consumption Pattern and Nutritional Security among Poor Rural Households: Impact of MGNREGA", Agricultural Economics Research Review, Vol. 26, No. 1, pp. 73-82.

- Mehrotra Santosh (2008), "NREG Two Years On: Where Do We Go From Here?", Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 43, No. 31, pp 28-36.

- Mishra Sushanta Kumar (2011), "Asset Creation Under MGNREGA: A Study in Three Districts of Madhya Pradesh", IMJ Journal, Vol. 3, No. 3, pp. 19-30.

- Nair K N (2009), "A Study of National Rural Employment Programme in Three Grama Panchayats of Kasaragod District", Working paper No. 413, Centre for Development Studies, Trivandrum, Kerala. Retrieved from www.cds.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/wp413.pdf

- Narayanan Sudha, Ranaware K, Das U and Kulkarni A (2014), "Mgnrega Works and Their Impacts: A Rapid Assessment in Maharashtra", Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research, Mumbai, Working Paper- 2014-042. http://www.igidr.ac.in/pdf/publication/WP-2014-042.pdf

- Panda B, Dutta A K and Prusty S (2009), "Appraisal of NREGA in the States of Meghalaya and Sikkim", Project Report submitted to Indian Institute of Management, Shillong. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/13619314/APPRAISAL_OF_ NREGA_IN_THE_STATES_OF_MEGHALAYA_AND_SIKKIM

- Pankaj A K and Sharma A N (2008), "Understanding the Processes, Institutions and Mechanisms of Implementation and Impact Assessment of NREGA in Bihar and Jharkhand", Institute of Human Development, New Delhi.

- Sadana N and Rath S (2010), "Gendered Risks, Poverty and Vulnerability in India: Case Study of the Indian Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (Madhya Pradesh)", Overseas Development Institute, London.

- Singh Parvindar (2013), "Nurturing the Lifeline: Community Participation and Social Audits in MGNREGS", Rural Livelihood Strategies. www.academia.edu/9961651/Nurturing_the_lifeline_Community_participation_and_social_audits_in_ MGNREGS

- Singh S P and Nauriyal D K (2009), "System and Process Review and Impact Assessment of NREGA in the State of Uttrakhand", Study Conducted by Indian Institute of Technology, Roorkee.

- Thakur A (2011), "A Study on MGNREGA and Its Impact on Wage and Work Relation", Corpus ID: 155036084, available at righttofoodindia.org

- UNDP (2013), "Empowering Lives Through Mahatma Gandhi NREGA". https://www.undp.org/india/publications/empowering-lives-through-mahatma-gandhi-nrega

- Vaidya C S and Singh R (2011), "Impact of NREGA on Wage Rate, Food Security and Rural Urban Migration in Himachal Pradesh", Report Submitted to the Ministry of Agriculture, Agro-economic Research Centre, Shimla, India.

- Venkatesh Athreya (2009), "Economic Crisis and Rural Livelihoods", M S Swaminathan Research Foundation, January, Chennai.