October'23

The IUP Journal of Organizational Behavior

Archives

Mediating Influence of Perceived Stress and Sleep Quality on Job Stress and Family Relationships: A Study on Working Professionals in India

Gunjan Aggarwal

PGT Psychology and Counsellor, St. Mary's School, Safdarjung, New Delhi, India; and is the corresponding author. E-mail: 25.gunjanaggarwal@gmail.com

Rashi

Research Executive, Quipper Research Pvt. Ltd, Mumbai, India. E-mail: rashiishuklaa@gmail.com

Pallavi Madan

Assistant Professor, Department of Psychology, JIMS, Rohini, Delhi, India.

E-mail: pallavi.madan @jimsindia.org

Job stress in working professionals has materialized as a pertinent contemporary concern. Increased demands at the workplace in combination with more personal responsibilities and activities have the potential to trigger work-family conflicts. This study focuses on the mediating influence of perceived stress and sleep quality on the relationship between job stress and family relationships. The sample consisted of 145 working professionals in the age group of 20 to 50 years, who were currently employed in various sectors. New Job Stress Scale, Brief Family Relationships Scale, Sleep Quality Scale, and Perceived Stress Scale were used for this study. The results, after running correlation and mediation analysis, showcased that job stress has a significant positive relationship with perceived stress and sleep quality and a negative correlation with family relationships. The findings of the double mediation analysis highlight the negative mediating effect of both perceived stress and sleep quality on the relationship between job stress and family relationships. The study also sheds light on the parallel mediating role of perceived stress and sleep quality. Additionally, the findings of the study show the need for designing mental health interventions at the workplace that can enhance employee wellbeing across all domains.

Introduction

With the rapid advancement of economies across the world, a massive number of people have become a part of the global workforce. This shift was largely witnessed over the past decades and has accounted for a steady rise in GDP and the worldwide labor force (World Economic Outlook, 2021). This influx has resulted in an increasingly diverse workplace as well, which may be characterized by a mix of age, gender, ethnic, and cultural backgrounds.

Working professionals have been a point of focus of many studies centered around a diverse range of variables such as job satisfaction, work-life balance, stress, workplace spirituality, leadership, etc. As the workforce continues to evolve, the need to explore the various factors that influence their wellbeing and productivity also becomes important in order to foster healthier and sustainable workplaces. While there may be policies in place that promote employee satisfaction and ensure retention, the employees still deal with multiple challenges while navigating through the ever-changing demands of the workplace.

The aim of this research is to explore whether sleep quality and perceived stress mediate the relationship between job stress and family relationships.

Literature Review

Organizational stress may occur as a result of an employee's negative perception of the organizational structure. WHO (2003) defined workplace stress as 'a pattern of physiological, emotional, cognitive and behavioral reactions to some extremely taxing aspects of work content, work organization and work environment'. Overwhelming work-related demands, incongruence between skills, abilities, and knowledge as well as the inability to cope with the work pressure could perhaps lead to work stress (WHO, 2003; and Houtman et al., 2007). Hence, job stress is characterized by the psychological challenges faced at the workplace due to excessive requests placed on individuals. Karasek (1979) propounded the job demands-control model to explain this occupational stress experienced by employees. The main proposition of this model is that the level of control possessed by employees influences the strain experienced due to job demands and enhances their job satisfaction. Research suggests that impractical demands, role conflict, lack of control, and communication all lead to a stress-inducing working climate (Bhui et al., 2016).

Job Stress and Family Relationships

Work-related stressors often get transmitted to different domains pertaining to an employee's life. Starting from internal processes like mood and cognition, the everyday job stressors tend to spill over and impact one's interactions in a social or familial context (Repetti and Wang, 2017). 'Work-family spillover' can be understood as the movement of various factors beginning from work towards family relationships. Since the boundary separating the two units is highly permeable, it allows the exchange of both positive and negative forces which influences an individual's functioning. A positive spillover from work to the family may include material rewards, enriching family interactions as a result of a good day at work, higher psychological safety and wellbeing, etc. (Gassman-Pines, 2011; and Repetti and Wang, 2014). Greenhause and Powell (2006) studied multiple positive outcomes of the dyadic nature of work and family domains in improving the quality of life of employees. However, a negative spillover of work may include job burden, conflicting work environment, etc. which affects the emotional and behavioral responses of the family collectively. The task performance of 596 subjects working in Portuguese organizations was studied in the context of work and family conflict experienced by them by Moreira et al. (2023). The results showed that the conflicts were significantly impacting the task performance of the employees, leading to decreased performance on the job.

In a study conducted by Lawson et al. (2013), the work-family spillover of 50 hotel employees was investigated. The results from the same suggested that higher stressful situations at the workplace lead to more negative work-family spillover. The interaction of the two hence holds implications for the overall wellbeing of individuals. Sanz-Vergel et al. (2011) also conducted research on 273 Spanish ambulance workers to study the nature of work-family interactions on their psychological and physical health by looking at the moderating role of sleep quality between this relationship. The results from the multiple regression analysis showed a significant moderation of sleep between work and family interactions, such that when the work-family interactions are positive, the individual gets enough restorative sleep and experiences less psychological strain. On the other hand, when the aforementioned interactions are negative, sleep is disturbed and there is high psychological strain experienced by the individual.

Role of Sleep Quality and Perceived Stress

Over the years, studies have focused on the impact of workload on the psychological states of people and have found some considerable results highlighting the relationship shared between job strain and sleep quality. Work overload is positively related to poor sleep quality, whereas balanced job situations have led to increased sleep quality (Williams et al., 2006; and Knudsen et al., 2007). The Effort-Recovery model proposed by Meijman and Mulder (1998) elucidated the role of psychobiological underpinnings of work stress and its effect on the overall wellbeing of a person. The model states the importance of recovery periods which are characterized by non-working hours and are experienced as 'free time' after work. The heightened stress levels can hamper the recovery and induce psychological reactions in a person which restricts the psychobiological system from returning to their baseline levels.

Sleep complaints are also associated with physical and psychosocial working conditions along with work-family conflicts (Lallukka et al., 2010). Furthering the research, several components of job strain such as job demands, job control, and job support were found to be correlated with sleepiness, sleep quantity, and sleep quality (Litwiller, 2014). The bidirectional nature of work-family conflict explains the impact of work demands on family/personal life and vice versa. These conflicts independent of other factors such as socio-demographics and other working or household conditions are related to inconsistent and disturbed sleep patterns of employees (Buxton et al., 2016). A study carried out on Malaysian working women discovered the age-related differences that acted out in the work and family spheres and caused significant sleep disturbances. The results showed that women in their 20s were majorly affected by increased strain-based and time-based work interference in their family life which caused sleep difficulties. On the other end, women in their 30s were largely impacted by family-based interference in work further leading to sleep disturbances. Women older than 40 experienced challenges in both the functional areas of work-family conflict and therefore the varied sleep patterns together accounted for the sleep disturbances that were being experienced by working women in Malaysia (Aazami et al., 2015).

'Work to family enrichment' as opposed to 'work to family conflict' has also marked improved sleeping patterns which has been found to be linked with hedonic balance. Affective experiences associated with the work-family interface have been examined to have a direct impact on employee's sleep quality (Magee et al., 2017). Studies indicate that poor sleep quality and sleep disturbances can have serious implications on a person's quality of life. Furthermore, when compared with good sleepers, persistent deterioration in sleep quality was found to be related to proneness to accidents, absenteeism at work, diminished positive emotions, and increased use of healthcare (Roth and Roehrs, 2003).

Relationships in the family play a crucial role in an individual's life. These family relationships contribute to the wellbeing of the individual (Merz et al., 2009). Research suggests that the presence of family members can influence the sleep of each member. Sleep is regulated by the potential interpersonal and emotional security within the family. In other words, families that have high interpersonal and emotional security might not impact the sleeping patterns of the family members, providing them with good sleep (Ailshire and Burgard, 2012). Further, different types of interactions among family members may also influence the nature of sleep. Research has showcased that families that have high relationship demands and lack support lead to detrimental effects on sleep (Durden et al., 2007). It has also been seen that more frequent contact between strained families, and negative impacts are witnessed in sleeping patterns. On the other hand, lack of sleep also impacts the relationships in the family. It has been witnessed that spouses who could not sleep the night before tend to have depressed mood states and indulge in fights the following day (Patron, 2022).

Family relationships are impacted by the stress levels of each family member. According to Stress Process theory, stress can impact the mental health of an individual, whereas social support acts as a protective factor in dealing with the same (Pearlin, 1999). Various stressors contribute to the smooth functioning of the family. These stressors could be arguments, fights, poor communication skills, exhaustion from busy days, fatigue, confusion in handling family relations, and dependence on alcohol or substance. Additionally, stressors like community violence, reduced access to medical services, economic hardships, and lack of opportunities also act as obstacles to the smooth functioning of the family (Sheidow et al., 2013).

Objective

The objectives of the study are as follows:

- To explore the relationship between job stress and family relationships.

- To study sleep quality in relation to job stress and family relationships.

- To explore the relationship between sleep quality and job stress.

- To explore the relationship between sleep quality and family relationships.

- To study perceived stress in relation to job stress and family relationships.

- To explore the relationship between perceived stress and job stress.

- To explore the relationship between perceived stress and family relationships.

- To understand whether sleep quality mediates the relationship between job stress and family relationships.

- To understand whether perceived stress mediates the relationship between job stress and family relationships.

- To understand if sleep quality and perceived stress parallelly mediate the relationship between job stress and family relationships.

Data and Methodology

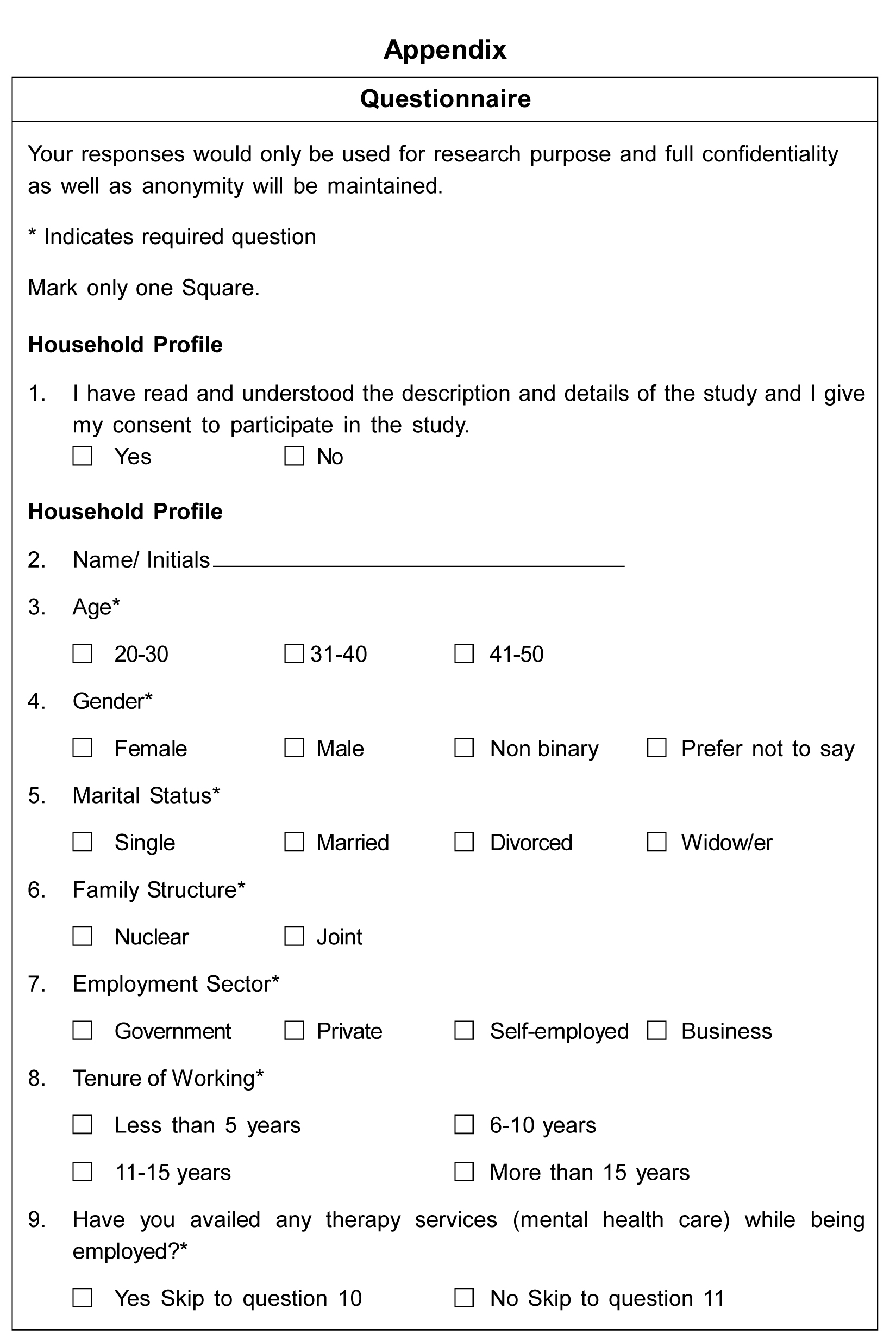

The study uses a correlational research design by collecting primary data using self-administered quantitative questionnaires (see Appendix). The study design involves studying relationships between multiple variables without having to manipulate any of them to draw conclusions.

The sample size was 145 working professionals falling in the age group of 20 to 50 years from different parts of India. The sampling techniques used for the recruitment of the participants were non-probability convenience sampling and snowball sampling. The data was collected through an online Google survey. The participants were eligible to enroll in the study if they fulfilled the age criteria and were currently employed.

Measures

Demographics

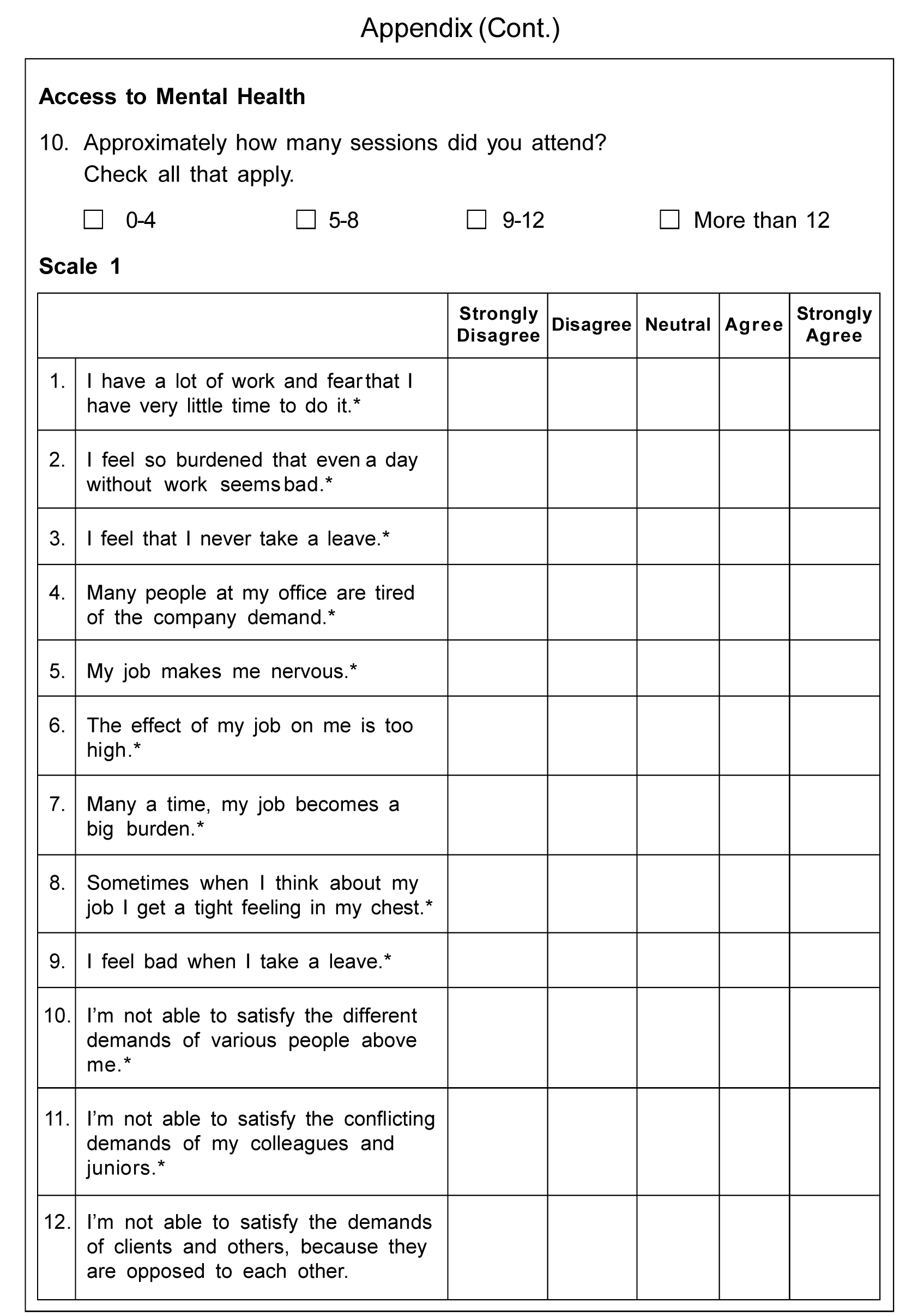

A demographic sheet was created for the study. It included information such as name, age, gender orientation, marital status, family structure, employment sector, and tenure of working. The participants were also asked if they had availed any therapy services while being employed followed by a question about the number of sessions attended.

Assessment of Job Stress

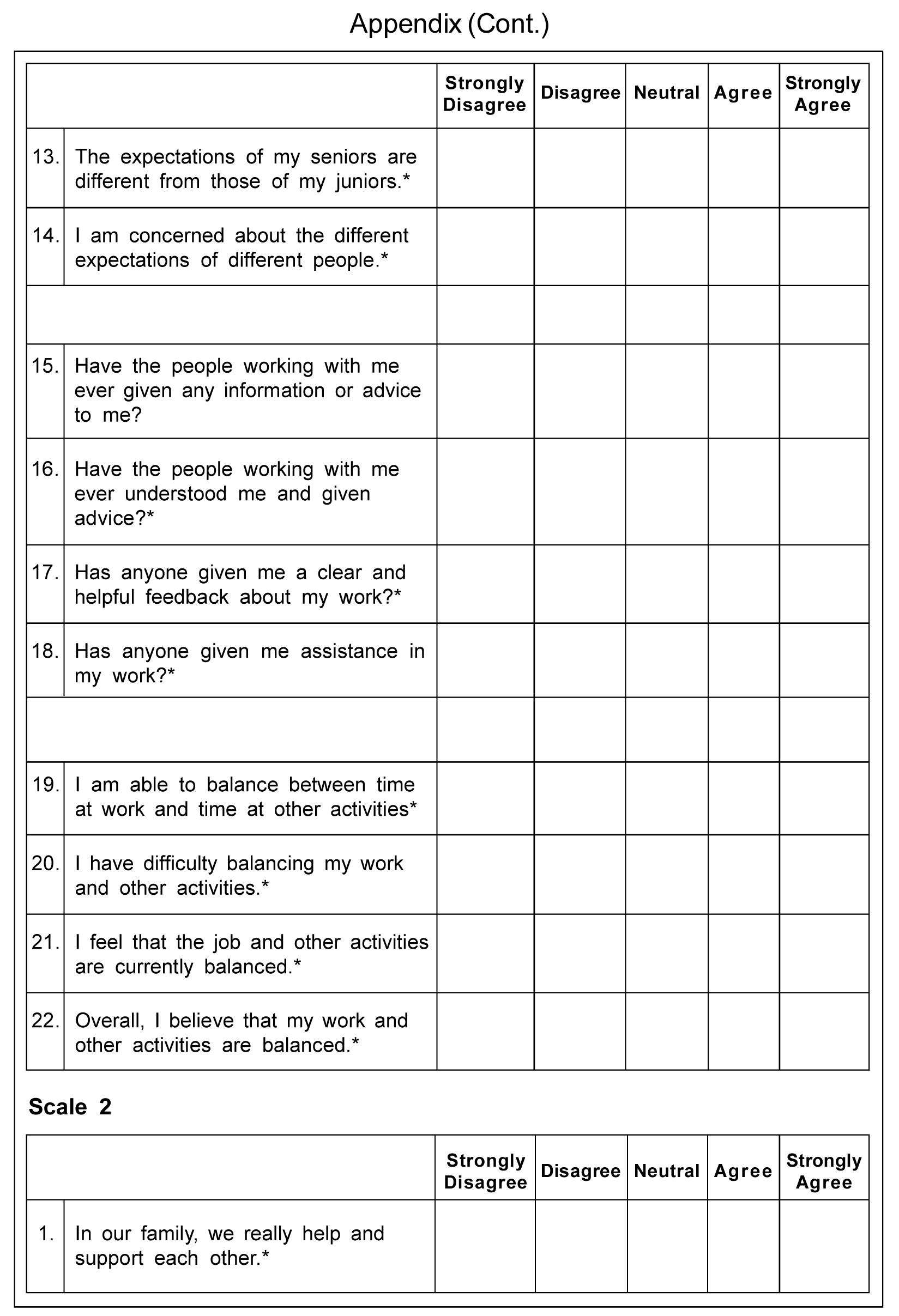

The new job stress scale was used to measure the job strain of working professionals who participated in the study. The scale was developed by Shukla and Srivastava (2016) that is most suitable for the Indian population. The scale consists of 22 items and assesses an extensive set of time stress, anxiety due to job, role expectation conflict, coworker support, and work-life balance. The overall reliability of the scale was 0.81 and the factor analysis revealed high construct validity. The scoring is done on a continuous scale by calculating the total of all items. High scores indicate high job stress whereas lower scores signify lower job stress which is based on the mean scores obtained from the data.

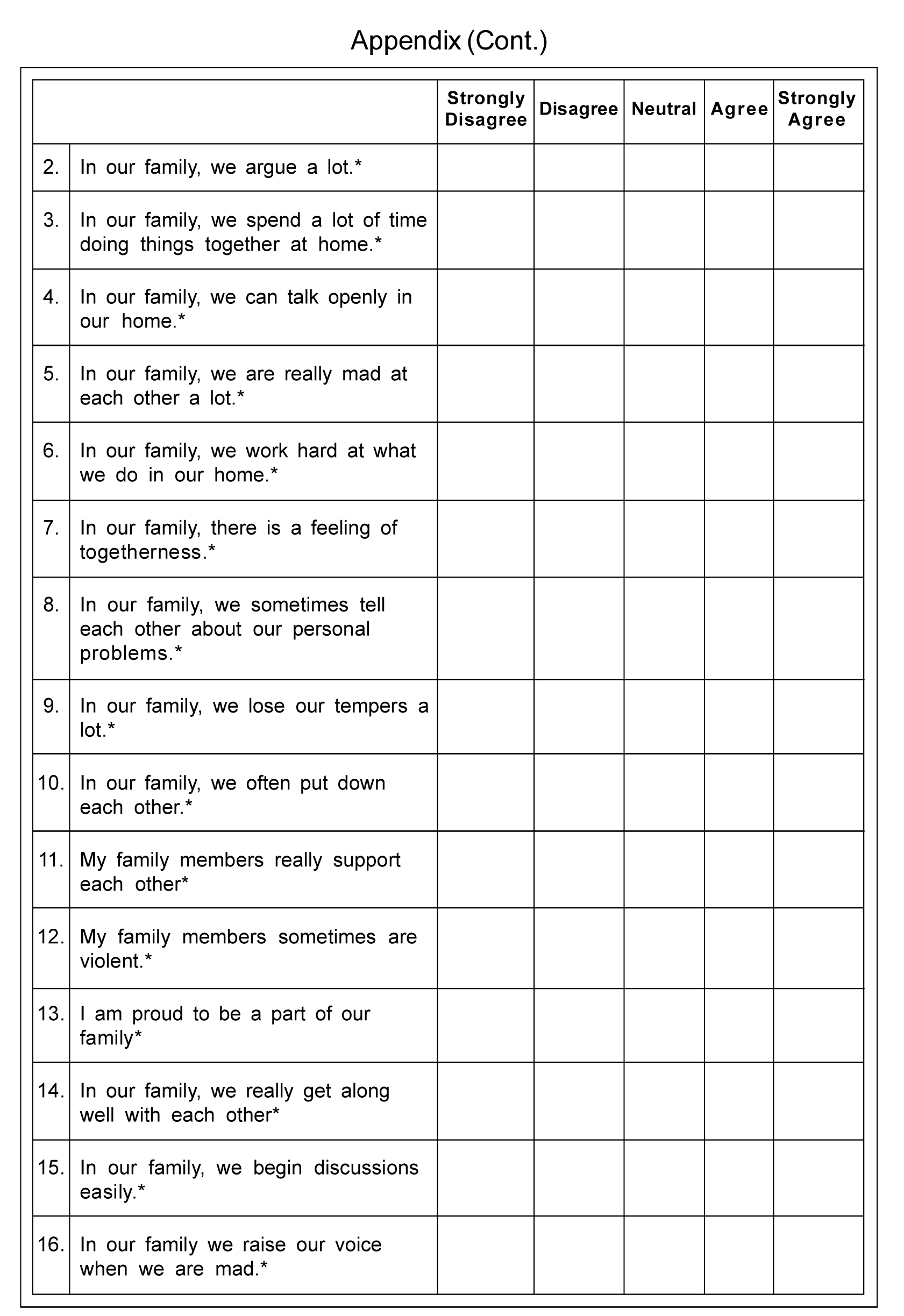

Assessment of Family Environment

The family relationship scale developed by Fok et al. (2011) was used to assess the family relationships from the family environment scale developed by Moos and Moos (1994). The scale covers three sub-dimensions, viz., expressiveness, cohesion, and conflict. With a total of 16 items, the scoring is done on a five-point Likert scale (strongly agree = 5, agree = 4, neutral = 3, disagree = 2, strongly disagree = 1). Specific norms are followed for each subscale and the scores are indicative of high average or low conflict in the family environment.

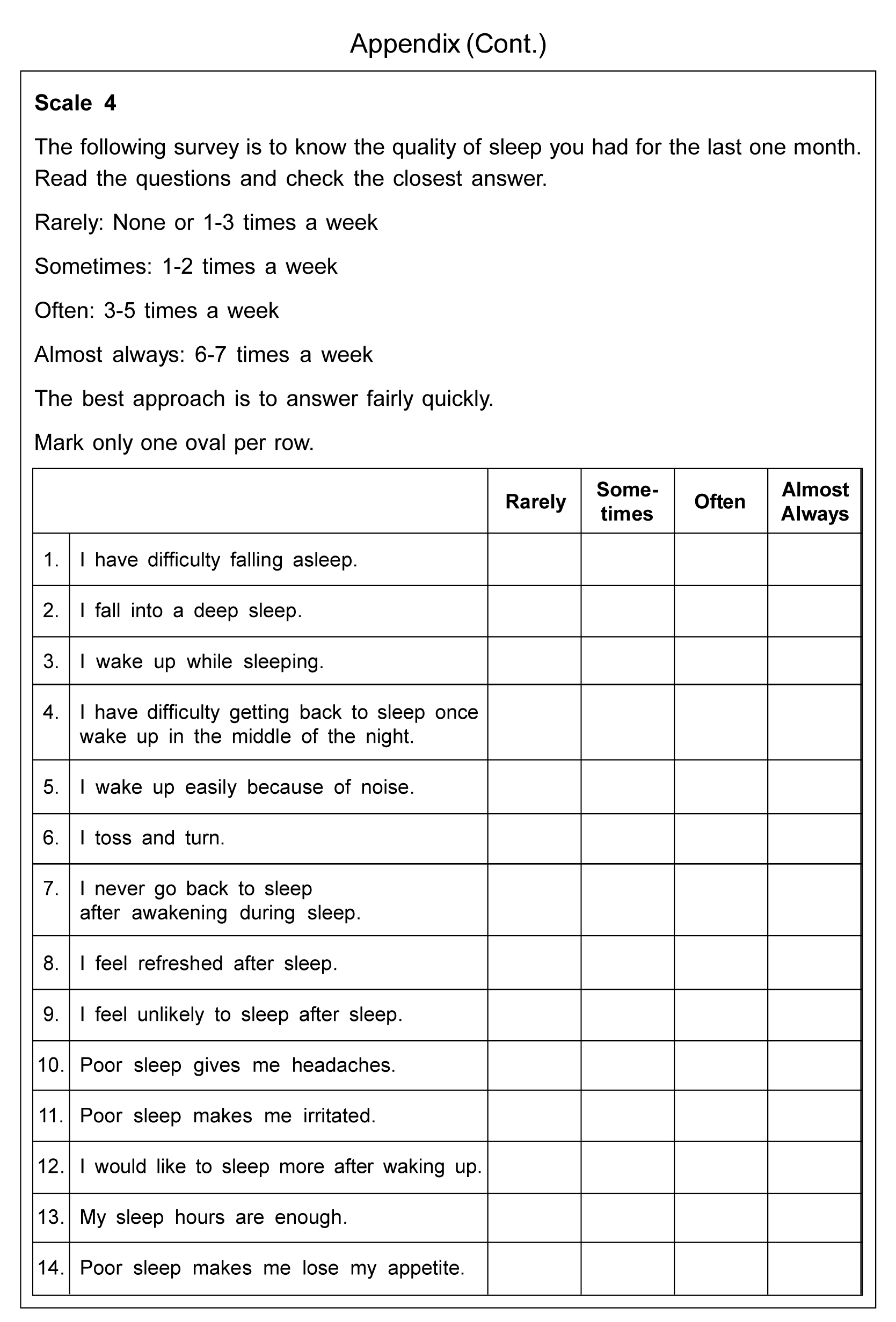

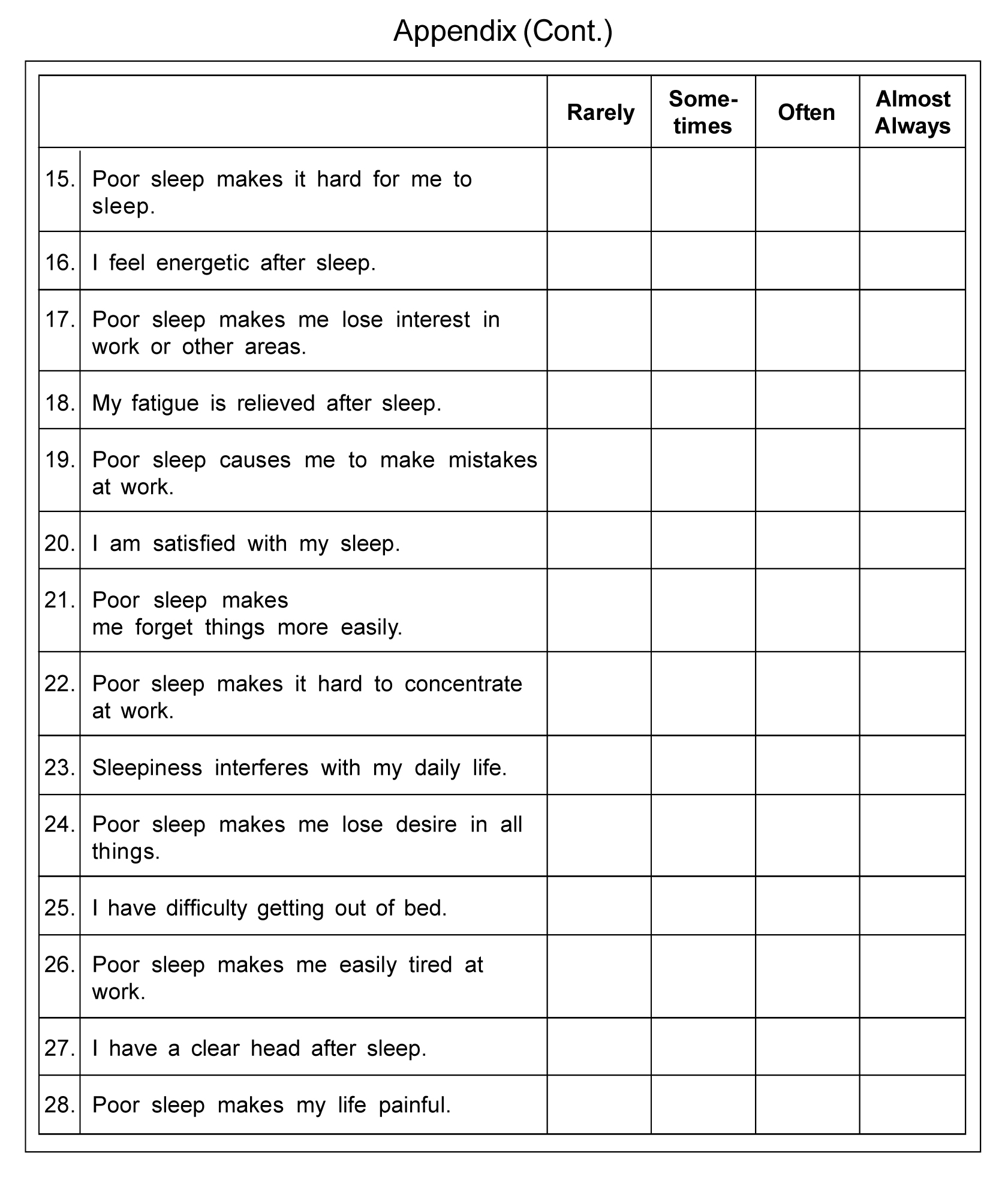

Assessment of Sleep Quality

Sleep quality scale (SQS) was developed by Yi et al. (2006) to assess the overall quality of sleep for the previous month. The scale comprises 28 items and measures scores across six factors, namely, daytime dysfunction, restoration after sleep, difficulty in falling asleep, difficulty in getting up, satisfaction with sleep, and difficulty in maintaining sleep. The scoring is done using a four-point Likert scale (few = 0, sometimes = 1, often = 2, almost always = 3). Scores on items in factors 2 (restoration after sleep) and 5 (satisfaction with sleep) have to be reversed before all the scores are summed. The range of scores is from 0 to 84, with a higher score indicating a lower sleep quality.

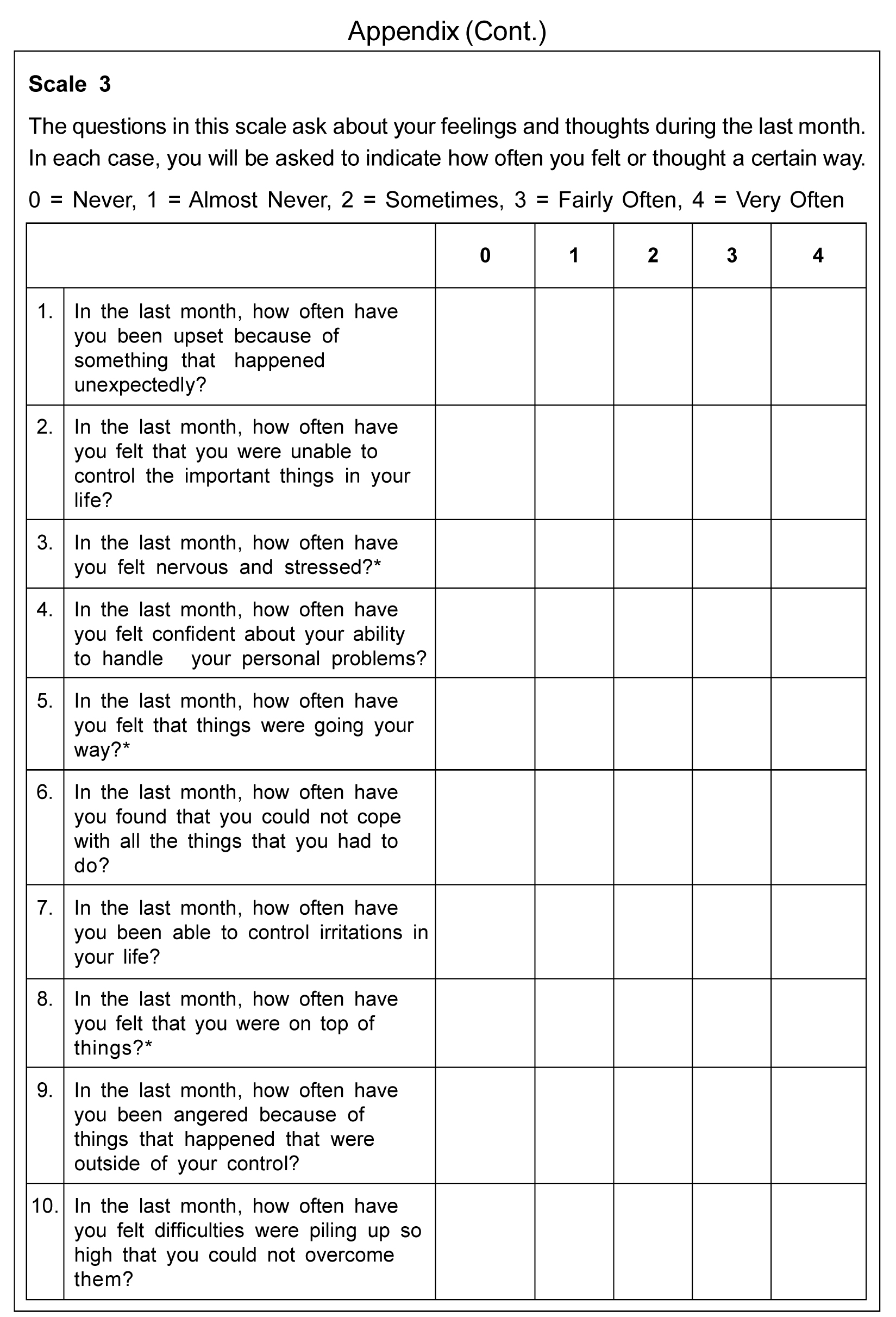

Assessment of Perceived Stress

Perceived stress scale (PSS) developed by Cohen et al. (1983) is a famous tool used to measure individual stress levels. It consists of 10 items and the scores are obtained on a five-point Likert scale (0 = never, 1 = almost never, 2 = sometimes, 3 = fairly often, 4 = very often). Scores for items 4, 5, 7, and 8 are reversed (4 = never, 3 = almost never, 2 = sometimes, 1 = fairly often, 0 = very often). PSS can range from 0 to 40 with higher scores indicating higher perceived stress.

Procedure

An online survey using Google Forms was circulated among working professionals in the age group of 20 to 50 years. There were four questionnaires in total which took an average time of 20 min to be filled. The data collection spanned over a period of 3 months from August 2021 to October 2021. The survey was voluntary and informed consent was taken from the participants before the questionnaires were distributed.

Results

The sample constituted 145 respondents. The age was divided into three categories- 20-30 years (n = 110, 75.9%), 31-40 years (n = 17, 11.7%), and 41-50 years (n = 18, 12.4%). The sample consisted of 68 males (46.9%), 76 females (52.4%), 0 non-binary and 1 preferred not to say (0.7%). 112 respondents (77.2%) belonged to the nuclear family structure whereas 33 respondents (22.8%) belonged to the joint family structure. 15 respondents (10.3%) work in the government employment sector, 102 respondents (70.3%) work in the private employment sector, 17 respondents (11.7%) are self-employed and 11 respondents (7.6%) have their own business. 98 respondents (67.5%) have less than 5 years of experience, 21 respondents (14.5%) have 6-10 years of experience, 8 participants (5.5%) have experience of 11-15 years and 18 respondents (12.4%) have experience of more than 15 years.

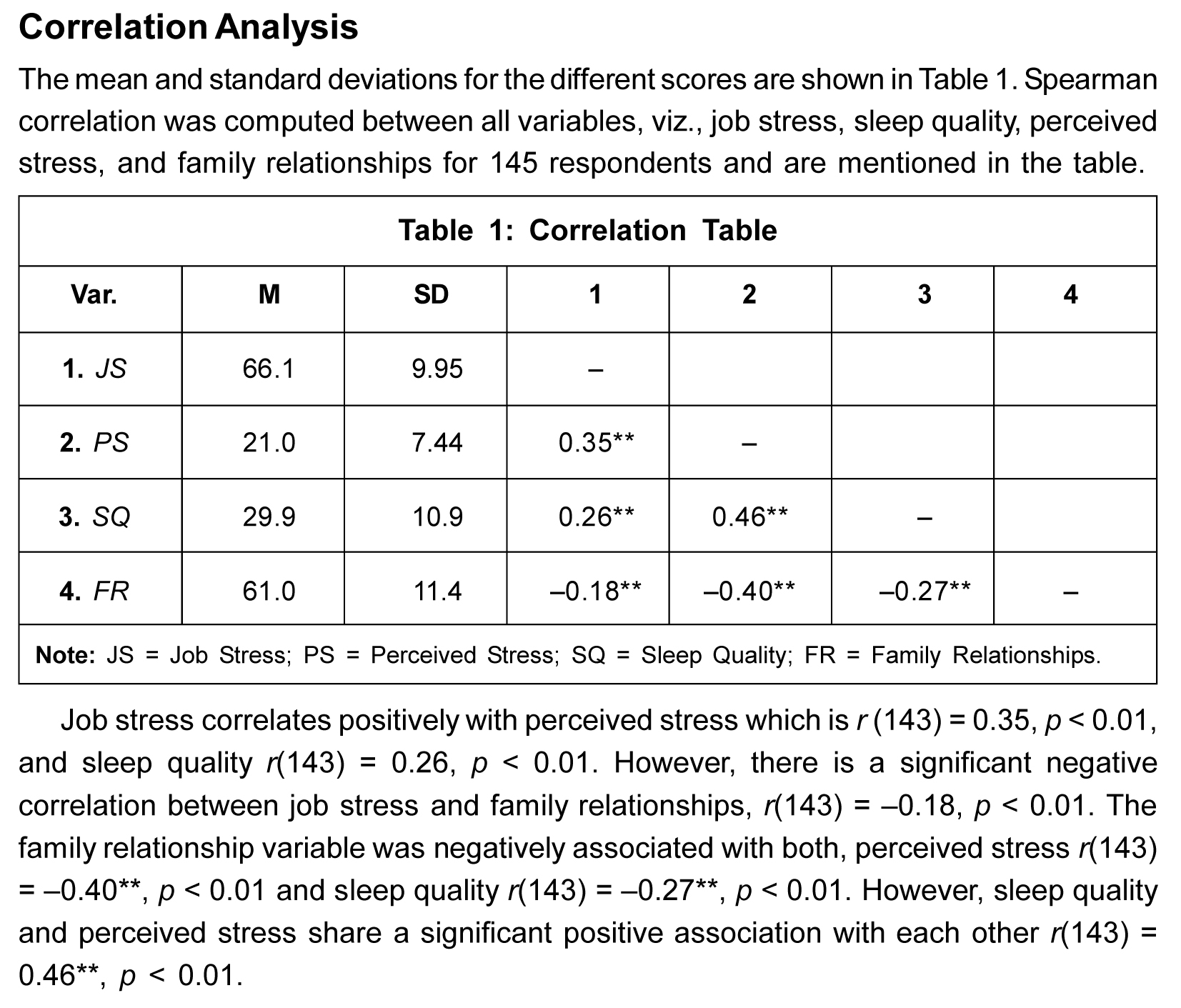

Mediation Analysis

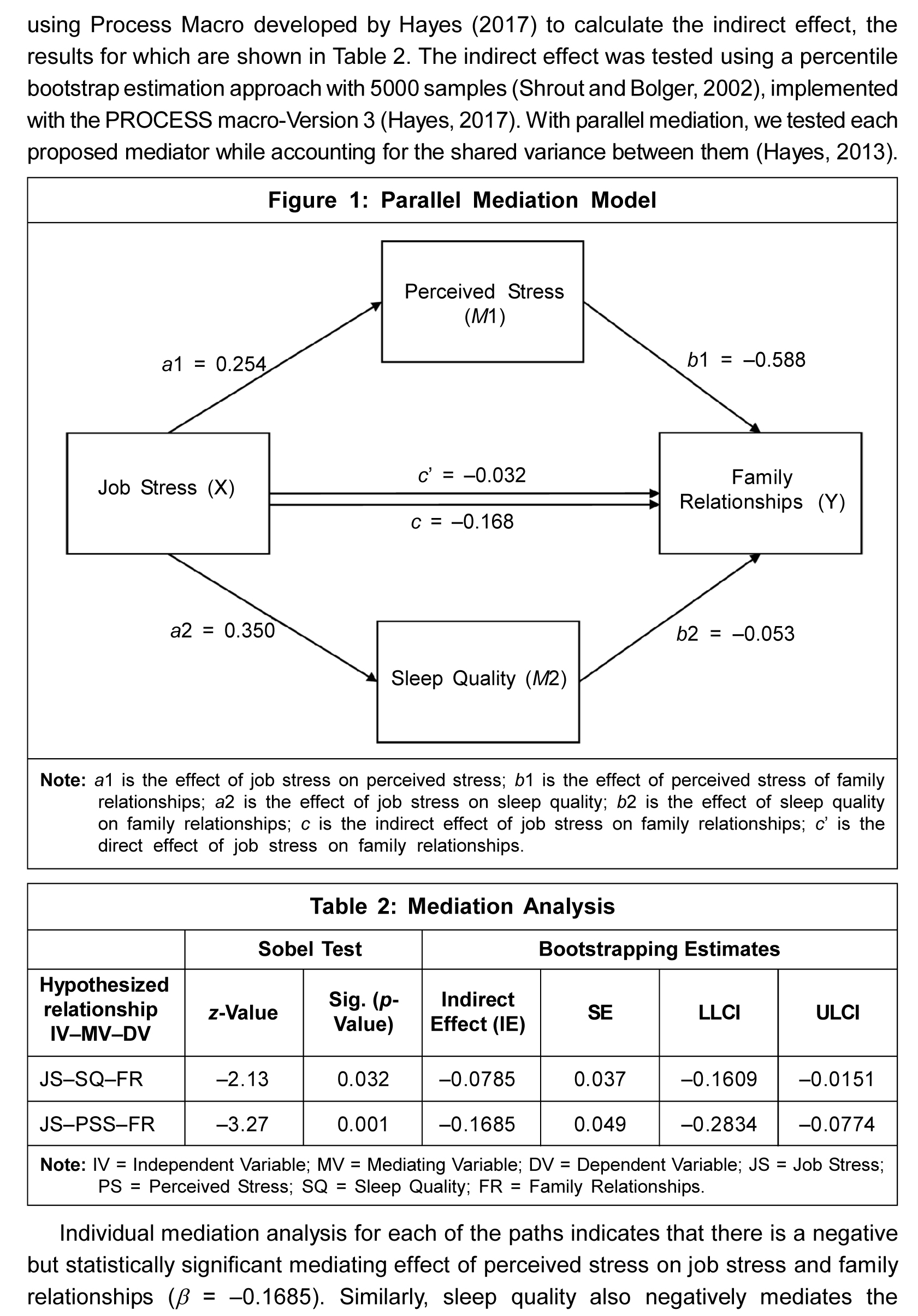

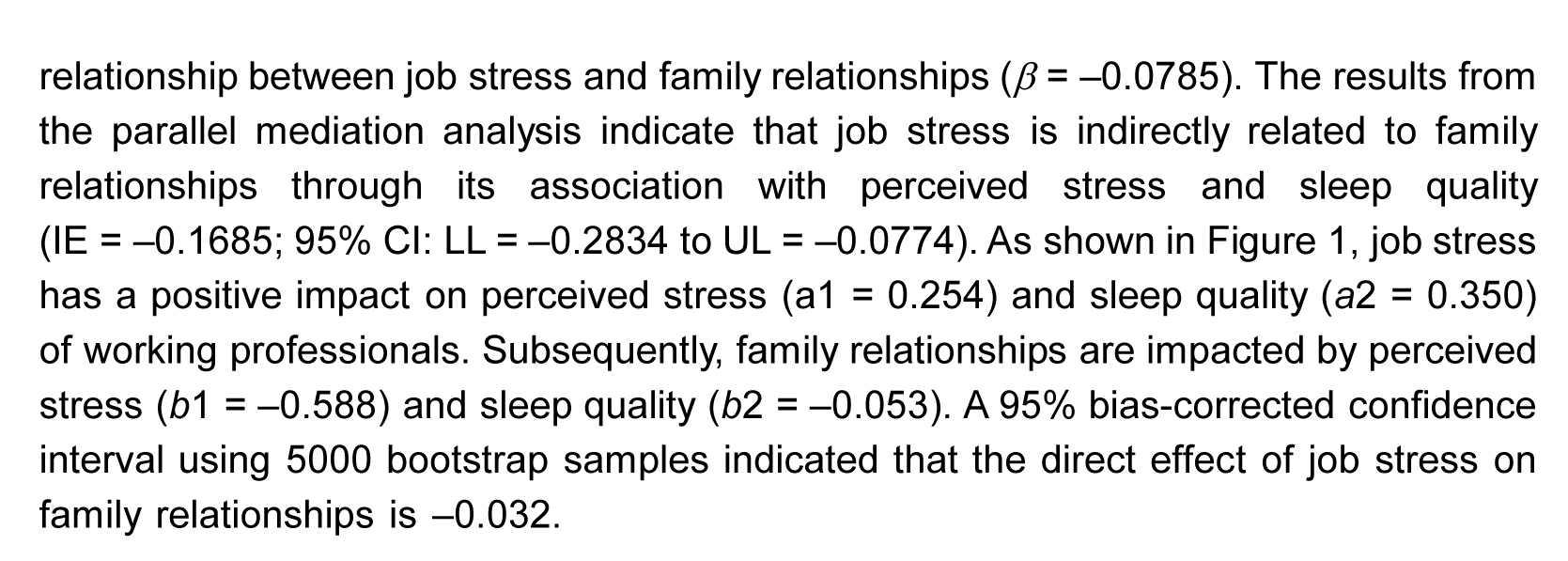

The mediation model which formed the basis for the current study is presented in

Figure 1. To test mediation, the analysis was done by running an online Sobel test and

Discussion

The study examined whether sleep quality and perceived stress mediate the relationship between job stress and family relationships. The purpose of the current study was to cultivate a model and look at the co-occurrence and interrelatedness between the selected variables. The results of the study indicate that there is a statistically significant negative mediating impact of sleep quality and perceived stress on the aforementioned relationship. The results of the parallel mediation analysis demonstrated a negative mediating effect of the two mediators.

Research suggests that sleep quality has shown a relationship with job stress and family relationships. The findings of the current study also showcased that sleep quality has a significant positive relationship with job stress, indicating that as job stress increases the concerns about sleep quality also increases. Job characteristics like repetition of tasks, multiple roles at the workplace, and lack of job autonomy could also lead to concerns with sleep quality (Knudsen et al., 2007). It was also found that sleep quality has a significant negative relationship with family relationships, indicating that as the quality of family relationships increases the concerns with sleep decrease. This further indicates that as the family scores higher on cohesion and expressiveness, they tend to have fewer sleep quality issues and vice versa. According to the scores, reduced family conflicts are associated with decreased worries about the quality of sleep. Various lifestyle factors like physical exercise, number of working hours, social support, or inability to stop thinking about work after working hours could play a role in determining sleep quality (Akersted et al., 2002). Furthermore, it was also seen that sleep quality has a significant negative mediating effect on job stress and family relationships. This means that individuals who experience high job stress may have concerns with sleep quality, impacting family relationships. This may be indicative of the potential spillover effects which may be due to high workload. Individuals who face issues at work could create problems in interpersonal relationships at home by initially impacting their sleep quality. Other issues that could lead to deterioration in sleep quality could be job insecurity, poorly coping with stress, an individual's perception of their working condition, difficulty in managing emotions, etc. (Burgard and Ailshire, 2009). Similar results were also reported by Magee et al. (2017) highlighting the affective experiences around work that link job stress and family relationships with sleep quality.

The study examined the relationship between job stress with perceived stress and reported a positive correlation shared by them. The finding implies an increase in job stress, lack of co-worker support, role conflict, and a lack of work-life balance leads to heightened perceived stress. Perceived stress was also found to be negatively correlated with family relationships, which highlights that the rise in perceived stress levels can have a negative impact on family relationships and the components they encapsulate such as cohesion, conflict, and expressiveness. Previous studies have found a significant positive correlation between perceived stress and work-family conflict which supports the findings of this study (Lourel et al., 2009; and Michel et al., 2010). The present study also investigated the mediating role of perceived stress between job stress and family relationships and postulated a negative mediating effect on the relationship shared by the mentioned variables. This finding is aligned with past research which reports that the experience of work-family conflict is linked with higher levels of stress in employees which is perhaps associated with the imbalance in performing both work and family roles (Panatik et al., 2012).

Perceived stress and sleep quality were also found to be positively correlated with each other. This indicates that as the scores on perceived stress increase, one's sleep quality scores also increase implying that the perception of situations as stressful leads to a worsening sleep quality. These findings are consistent with the research conducted by Sadeh et al. (2004) and Zhao et al. (2020), suggesting that perhaps sleep disturbances are influenced by several stressors experienced and an inability to cope with them. Another objective of the study was to study the parallel mediation of the two mediators, viz., perceived stress and sleep quality on the relationship between job stress and family relationships. The results from the analysis showed a negative total mediation of the two on the relationships, with perceived stress playing the dominant mediating role between the two.

Implications

The study highlights that job stress influences not only one's physical health but also mental health. Increased number of hours at work, role conflict, lack of support, etc. lead to poor sleep quality as well as intense stress which furthermore impacts the relationships. With these findings, the importance of managing stress at the workplace and improving the working conditions of employees becomes all the more important for it has significant repercussions in other domains of their lives. Providing support through employee wellness programs and focusing on the importance of positive mental health could be a few ways through which the goal is accomplished. E-mental healthcare, a modern term, has shown considerable potential in improving people's mental health. The benefits of these services are that it is low cost and easily accessible, and maintains the confidentiality and anonymity of the user. These services can be availed using different apps, links, Internet-based programs, games, appointments with professionals, peer support services, etc. (Moock, 2014).

Conclusion

The study examined the mediating effect of perceived stress and sleep quality between job strain and family relationships. Correlational analysis revealed that there were significant relationships between job stress, sleep quality, perceived stress, and family relationships. The findings thus underscore the importance of addressing the job-related stressors not only for the wellbeing of individuals but also to preserve the harmony of the familial unit. Interventions aimed at the same with the focus on reducing stress, promoting healthy sleep habits, and offering wellness programs to support their wellbeing can also impact their productivity and efficiency at the workplace.

Limitations and Future Scope: While the study has led to certain imperative findings that can be used for further studies, it is not without limitations. First, a small sample size which consists of people hailing from urban settings in India could have limited the scope of generalizability. Second, an unequal representation of the population, i.e., a skewed male-to-female ratio might have influenced the results. Third, the occurrence of Covid-19 and its impact on people's mental and physical health due to the transition from offline work setups to online work from home might have also influenced the responses.

Future research conducted on this topic could focus on building interventions around the variables to ascertain causality. The role of counseling/psychotherapy could also be studied in relation to these variables to bring forth its benefits and importance in improving stress, sleep quality, and relationships.

References

- Aazami S, Akmal S and Shamsuddin K (2015), "A Model of Work-Family Conflict and Well-Being Among Malaysian Working Women", Work, Vol. 52, No. 3, pp. 687-695. doi:10.3233/wor-152150

- Ailshire J A and Burgard S A (2012), "Family Relationships and Troubled Sleep Among US Adults", Journal of Health and Social Behavior, Vol. 53, No. 2, pp. 248-262. doi:10.1177/0022146512446642

- Akerstedt T, Knutsson A, Westerholm P et al. (2002), "Sleep Disturbances, Work Stress and Work Hours", Journal of Psychosomatic Research, Vol. 53, No. 3, pp. 741-748. doi:10.1016 /s0022-3999(02)00333-1

- Bhui K, Dinos S, Galant-Miecznikowska M et al. (2016), "Perceptions of Work Stress Causes and Effective Interventions in Employees Working in Public, Private and Non-Governmental Organisations: A Qualitative Study", BJPsych Bulletin, Vol. 40, No. 6, pp. 318-325. doi:10.1192/pb.bp.115.050823

- Burgard S A and Ailshire J A (2009), "Putting Work to Bed: Stressful Experiences on the Job and Sleep Quality", Journal of Health and Social Behavior, Vol. 50, No. 4, pp. 476-492. doi:10.1177/002214650905000407

- Buxton O M, Lee S, Beverly C et al. (2016), "Work-Family Conflict and Employee Sleep: Evidence from IT Workers in the Work, Family and Health Study", Sleep, Vol. 39, No. 10, pp. 1871-1882. https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.6172

- Cohen S, Kamarck T and Mermelstein R (1983), "A Global Measure of Perceived Stress", Journal of Health and Social Behavior, Vol. 24, pp. 385-396.

- Durden Emily D, Hill Terrence D and Angel Ronald J (2007), "Social Demands, Social Supports, and Psychological Distress among Low-Income Women", Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, Vol. 24, No. 3, pp. 343-361.

- Gassman-Pines A (2011), "Associations of Low-Income Working Mothers Daily Interactions With Supervisors and Mother-Child Interactions", Journal of Marriage and Family, Vol. 73, No. 1, pp. 67-76. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00789.x

- Greenhaus J H and Powell G N (2006), "When Work And Family Are Allies: A Theory Of Work-Family Enrichment", Academy of Management Review, Vol. 31, No. 1, pp. 72-92. doi:10.5465/amr.2006.19379625

- Handbook of Work and Organizational Psychology, 2nd Edition, pp. 5-33, Psychology Press/Erlbaum, Hove, UK.

- Hayes A F (2013), "Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process analysis", A Regression-Based Approach, The Guilford Press, New York, NY.

- Hayes F A (2017,) "Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical Mediation Analysis in the New Millennium", Communication Monographs, Vol. 76, No. 4. doi: 10.1080/0363775 0903310360

- Houtman I, Jettinghof K and Cedillo L (2007), "World Health Organization. Occupational and Environmental Health Team, Raising Awareness of Stress at Work in Developing Countries: Advice to Employers and Worker Representatives", World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42956

- Karasek R A (1979), "Job Demands, Job Decision Latitude, and Mental Strain: Implications for Job Redesign", Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 24, No. 2, pp. 285-308.

- Knudsen H K, Ducharme L J and Roman P M (2007), "Job Stress and Poor Sleep Quality: Data from an American Sample of Full-Time Workers", Social Science & Medicine, Vol. 64, No. 10, pp. 1997-2007. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.020

- Lallukka T, Rahkonen O, Lahelma E and Arber S (2010), "Sleep Complaints in Middle-Aged Women and Men: The Contribution of Working Conditions and Work-Family Conflicts", Journal of Sleep Research, Vol. 19, No. 3, pp. 466-477. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2869.2010.00821.x

- Lawson K M, Davis K D, Crouter A C and O'Neill J W (2013), "Understanding Work-Family Spillover in Hotel Managers", International Journal of Hospitality Management, Vol. 33, pp. 273-281. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2012.09.003

- Litwiller B (2014), "The Relationship Between Sleep and Work: A Meta-Analysis". https://shareok.org/handle/11244/10396

- Lourel M, Ford M, Gamassou C E et al. (2009), "Negative and Positive Spillover between Work and Family: Relationship with Perceived Stress and Job Satisfaction", Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 24, No. 5, pp. 438-449. doi:10.1108/0268 3940910959762

- Magee C A, Robinson L D and Mcgregor A (2017), "The Work-Family Interface and Sleep Quality", Behavioral Sleep Medicine, Vol. 16, No. 6, pp. 601-610. doi:10.1080/1540 2002.2016.1266487

- Merz E, Schuengel C and Schulze H (2009), "Intergenerational Relations Across 4 Years: Well-being Is Affected by Quality, Not by Support Exchange", The Gerontologist, Vol. 49, No. 4, pp. 536-548. doi:10.1093/geront/gnp043

- Michel J S, Mitchelson J K, Pichler S and Cullen K L (2010), "Clarifying Relationships Among Work and Family Social Support, Stressors, and Work-Family Conflict", Journal of Vocational Behavior, Vol. 76, No. 1, pp. 91-104

- Moock J (2014), "Support from the Internet for Individuals with Mental Disorders: Advantages and Disadvantages of e-Mental Health Service Delivery", Frontiers in Public Health, Vol. 2. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2014.00065

- Moos R H and Moos B S (1994), Family Environment Scale Manual, 3rd Edition, Consulting Psychologists Press, Palo Alto, CA.

- Moreira A, Encarnacao T, Viseu J and Au-Yong-Oliveira M (2023), "Conflict (Work-Family and Family-Work) and Task Performance: The Role of Well-Being in this Relationship", Administrative Sciences, Vol. 13, No. 4, p. 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/adm sci13040094

- Panatik S A B, Rajab A, Badri S K Z et al. (2012), "Work-Family Conflict, Stress and Psychological Strain in Higher Education", International Conference on Education and Management Innovation, Vol. 30, pp. 67-71.

- Patron N (2022), "How Lack of Sleep Can Ruin Your Marriage. Retrieved from https://www.alaskasleep.com/blog/how-lack-of-sleep-can-ruin-your-marriage

- Pearlin L I (1999), "Stress and Mental Health: A Conceptual Overview", in A V Horwitz and T Scheid (Eds.), A Handbook for the Study of Mental Health: Social Contexts, Theories, and Systems, pp. 161-175, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- . Hunter L (2014, April 14), "Poor Sleep Has Social Causes and Consequences", Retrieved from https://www.prb.org/resources/poor-sleep-has-social-causes-and-consequences/

- Repetti R L and Wang S (2014), "Employment and Parenting", Parenting, Vol. 14, No. 2, pp. 121-132. doi:10.1080/15295192.2014.914364

- Repetti R L and Wang S (2017), "Effects of Job Stress on Family Relationships", Current Opinion in Psychology, Vol.13, pp. 15-18. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.03.010

- Roth T and Roehrs T (2003), "Insomnia: Epidemiology, Characteristics, and Consequences", Clinical Cornerstone, Vol. 5, No. 3, pp. 5-15.

- Sadeh A, Keinan G and Daon K (2004), "Effects of Stress on Sleep: the Moderating Role of Coping Style", Health Psychol, Vol 23, No. 5, p. 542.

- Sanz-Vergel A I, Demerouti E, Mayo M and Moreno-Jimenez B (2011), "Work-Home Interaction and Psychological Strain: The Moderating Role of Sleep Quality: Work-Home Interaction and Sleep Quality", PsychologieAppliquee [Applied Psychology], Vol. 60, No. 2, pp. 210-230.

- Sheidow A J, Henry D B, Tolan P H and Strachan M K (2013), "The Role of Stress Exposure and Family Functioning in Internalizing Outcomes of Urban Families", Journal of Child and Family Studies, Vol. 23, No. 8, pp. 1351-1365. doi:10.1007/s10826-013-9793-3

- Shukla A and Srivastava R (2016), "Development of Short Questionnaire to Measure an Extended Set of Role Expectation Conflict, Coworker Support and Work-Life Balance: The New Job Stress Scale", Cogent Business & Management, Vol. 3, No. 1, p. 1. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2015.1134034

- Shrout P E and Bolger N (2002), "Mediation in Experimental and Nonexperimental Studies: New Procedures and Recommendations", Psychological Methods, Vol. 7, No. 4, pp. 422-445. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422

- Williams A, Franche R-L, Ibrahim S et al. (2006), "Examining the Relationship Between Work-Family Spillover and Sleep Quality", Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, Vol. 11, No. 1, pp. 27-37. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.11.1.27

- World Economic Outlook (2021), October 25. Retrieved from https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO

- World Health Organization (2003), Authored by: Cassitto M G, Fattorini E, Gilioni R, Rengo C and Gonik V, "Raising Awareness of Psychological Harassment at Work", Protecting Workers' Health Series No. 4, Geneva, WHO.

- Yi H, Shin K and Shin C (2006), "Development of the Sleep Quality Scale", Journal of Sleep Research, Vol. 15, No. 3, pp. 309-316.

- Zhao X, Lan M, Li H and Yang J (2021), "Perceived Stress and Sleep Quality Among the Non-Diseased General Public in China during the 2019 Coronavirus Disease: A Moderated Mediation Model", Sleep Medicine, Vol. 77, pp. 339-345. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2020.05.021