April'23

The IUP Journal of Organizational Behavior

Archives

Impact of Work from Home on Employee Engagement: A Study on the Push and Pull Factors in IT Sector

Perikala Umapathi

Assistant Professor, Department of MBA, CMR College of Engineering & Technology (CMRCET), Kandlakoya, Hyderabad, Telangana, India; and is the corresponding author. E-mail: umapathi.1234@gmail.com

Shesadri Kiran Tharimala

Assistant Professor, Department of MBA, CMR College of Engineering & Technology (CMRCET), Kandlakoya, Hyderabad, Telangana, India. E-mail: seshadri.kiran@gmail.com

Work From Home (WFH) is a recent trend in organizations to maintain and improve employee engagement. Studies have examined the impact of WFH experience on employee engagement. This study aims to test a comprehensive and integrated model of various constructs taken from the literature, to understand the impact of WFH on employee engagement. The results confirm that the factors of WFH experience had significant impact on employee engagement. The study found that the pull and push factors considered had moderating effect on the model. The model was also found to be empirically robust. Human resource practitioners should, therefore, take note of the factors that promote employee engagement. The study suggests that firms should formulate and adopt new strategies to strengthen WFH to motivate employees as well as to create employee loyalty.

Introduction

The idea of Work From Home (WFH) represents a revolution in the way work is traditionally done. For a majority of employees, it was their first experience due to the Covid-19 pandemic, which affected almost every industry, including education. Employees in an organization range from recent graduates to highly experienced professionals (Sridevi, 2021). The idea of working in an organization where employees are not forced to commute to a single, central location is known as WFH. The terms "telework," "telecommuting," and "remote work" all refer to the same phenomenon. WFH has evolved over time. Because of the advancements in technology, employees can now operate successfully and efficiently without spending the entire day at their desks in the office. Employees across the world are now compelled to WFH due to the recent Covid-19 pandemic. Most nations, including India, urged workers to stay at home and steer clear of social events to prevent infections.

Studies have proved that working from home has advantages for both businesses and employees, as well as for society at large (Buciuniene et al., 2019). Since WFH is free from geographic conditioning, employers can choose from a larger talent pool. A distributed workforce supports business continuity in the event of an undesirable event, such as natural calamities, which lowers the risks. WFH can increase productivity compared to the traditional working environment (Golden and Veiga, 2008; and Fonner and Roloff, 2010). Additionally, research shows that WFH reduces organizational costs and employee turnover (Bloom et al., 2013)

When it comes to the advantages of working from home for employees, it helps cut down on commute time. This is crucial in the Indian context because individuals spend 7% of their day traveling (Tremblay and Thomsin, 2012). It lowers travel expenses and other related expenses (Morgan, 2004). Employee stress levels are reduced by working from home, and work-life balance is enhanced (Fonner and Roloff, 2010; and Bloom

et al., 2013). Additionally, it is clear from the studies that working from home increases one's autonomy (Harpaz, 2002), family and leisure time (Ammons and Markham, 2004; and Johnson et al., 2007), job satisfaction (Pratt, 1999; and Gurstein, 2001), and eliminates the distractions that come from co-workers (Golden and Veiga, 2008).

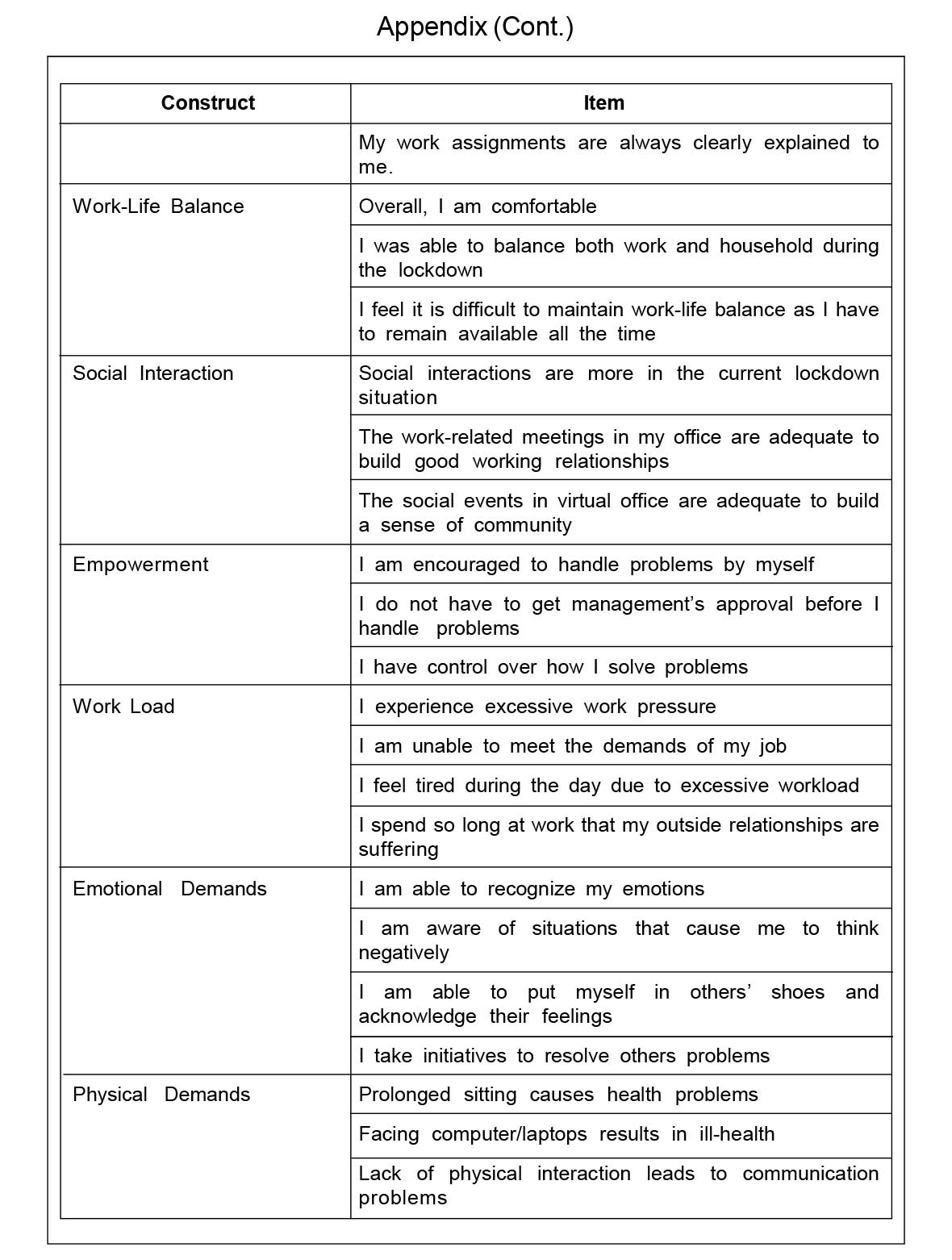

It is evident from the various research studies that both pull factors and push factors are showing their impact on WFH and employee engagement. Pull factors inspires and energizes employees to engage with the organization and push factors changes the strength of a relationship between WFH experience and employee engagement. Whereas, push factors influences the strength and direction of the relationship between WFH experience and employee engagement (Joubert, 2014). It is clear that due to the Covid-19 pandemic, almost all the organizations in the Information Technology industry shifted to WFH work culture. Against this background, this paper intends to analyze the significant impact of WFH on employee engagement. Further, studies show the mediating and moderating effect of pull and push factors, respectively, in honing employee engagement. Figure 1 shows the research model constructed for the study.

Literature Review

Employees who WFH do so from the convenience of their own homes. People who WFH have more freedom during their everyday work hours. Additionally, working from home allows people to maintain a work-life balance, while assisting businesses in completing their objectives (Abiddin et al., 2022). Working from home gives employees the freedom to balance between work and family, enabling a good work-life balance over the long term. Due to the unanticipated Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, millions had to work remotely, which unintentionally led to a global telecommuting experiment. After that, working from home quickly became the new standard in a matter of weeks (Wang et al., 2021).

Home-based workers aim to create a comfortable working environment that is equivalent to that of a regular office, including isolation, excellent lighting, and enough supplies. For mobile skilled workforce, the most crucial physical workplace requirements are the availability of workspace, space organization, ambient environment, and Internet and Wi-Fi connection. To maintain a balance between their personal and professional lives, remote employees erect boundaries, both literal and metaphorical (Aropah and Sumertajaya, 2020). Stevenson and Wolfers (2009) analyzed whether working from home would be more or less beneficial to overall life satisfaction based on how work and personal life interact. Working from home benefits employees in more ways than just saving them the daily commute: it boosts productivity and promotes healthier lifestyles. Because of its flexibility, it is a win-win arrangement that employees enjoy. It has numerous advantages, including a rise in productivity, a decrease in stress, and improved staff communication (Umapathi and Mounica, 2022).

Joubert (2014), in his comprehensive Engagement Predictive model, empirically explained that there are potential push and pull factors that could enable or inhibit engagement of individual employees.The pull factors are the forces which inspire and energize employees towards their engagement towards an organization, and the push factors block employee engagement. The study considered pull factors, viz., autonomy, performance feedback, quality of supervision, work-life balance, social interaction and empowerment, and push factors, viz., work overload, emotional demands and physical demands (Joubert and Roodt, 2019).

The freedom and convenience that come with working remotely are highly valued by employees. They value the advantages that they are willing to put in extra time at night and even on holidays to make up for the lost time (Coso, 2017). Managers should concentrate on enabling remote working conditions so that employees can balance work and family life in this new environment, and thus achieve employee engagement. Understanding employees' expectations, future objectives, and participation in organizational decisions and practices, or empowerment, is a further issue to be addressed (De-la-Calle-Duran and Rodriguez-Sanchez, 2021). A study conducted in the US found benefits from shorter commutes, more flexible work schedules, and higher productivity. Employers have invested in technology and changed the procedures to encourage WFH. According to Barrero et al. (2021), use of WFH will continue to be four times more common than it was before the pandemic, thus requiring investigation into the factors that affect the WFH situation.

Objective

The objectives of the study are:

- To study the impact of WFH experience on employee engagement.

- To examine the role of pull factors as a mediator between WFH experience and employee engagement.

- To test the moderating effect of push factors on the relationship between WFH experience and employee engagement.

Hypotheses

Based on the objectives, the following hypotheses have been formulated.

H1: There is a significant direct effect of WFH experience on employee engagement.

H2: Pull factors have a significant mediating role between WFH experience and employee engagement.

H3: There is a significant positive moderation effect of push factors on the relationship between WFH experience and employee engagement.

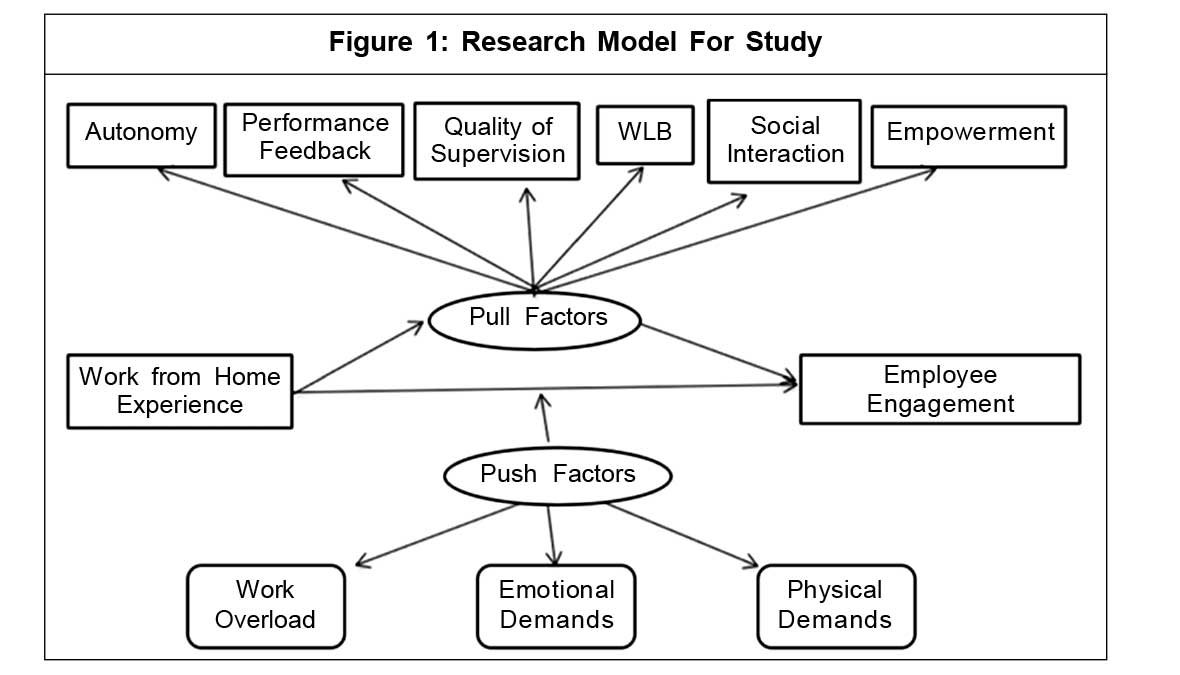

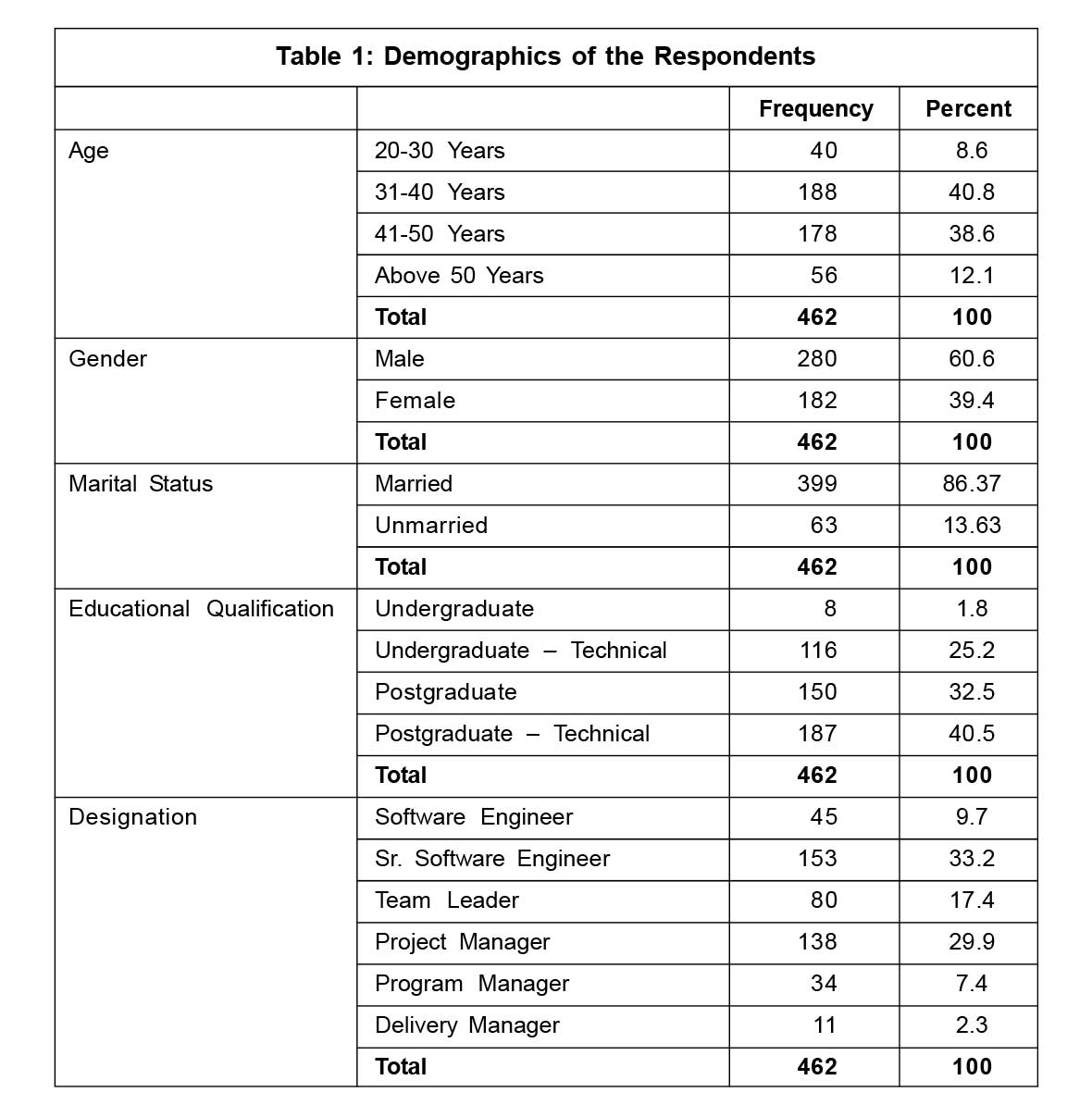

Data and Methodology

IT employees working from home in Hyderabad region were considered as the sample population of the study. Convenient sampling technique was adopted to select the sample size. Non-probability sampling technique was used in the study (Shiu et al., 2009). But the increase in sample size enhances the quality of output and also increases the precision value (Stockwell et al., 2002). Hence, to increase the accuracy of the output and also to decrease standard error, an attempt was made to fix the sample size as 462. The sample profile is shown in Table 1.

In order to analyze the primary data which was collected through a structured questionnaire (see Appendix), covariance-based structural equational modeling was adopted. This test was considered as the best to test the hypotheses of the proposed model (Wong, 2013).

Analysis

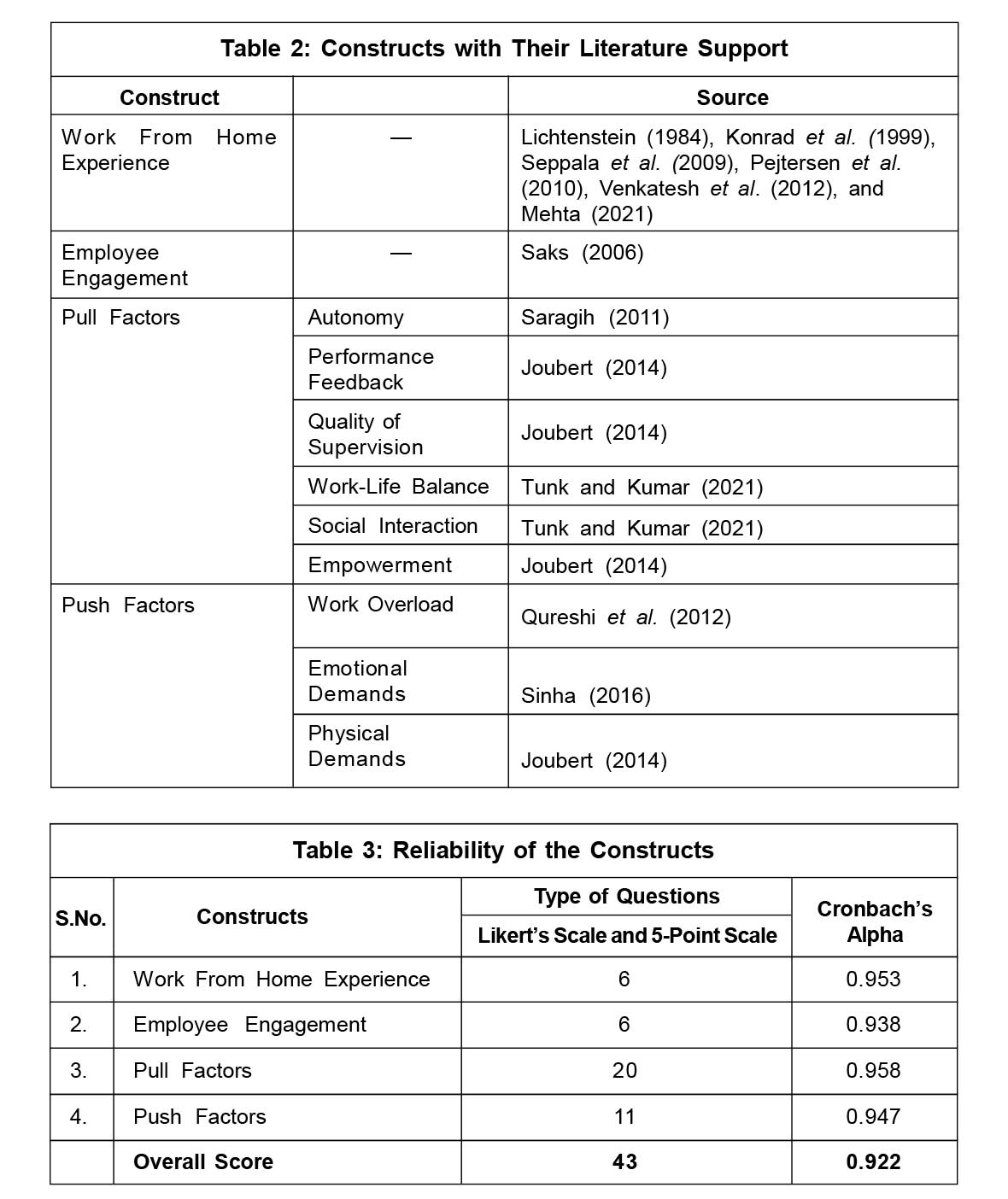

The measures in the study were adopted from literature. Construct-wise literature support is presented in Table 2.

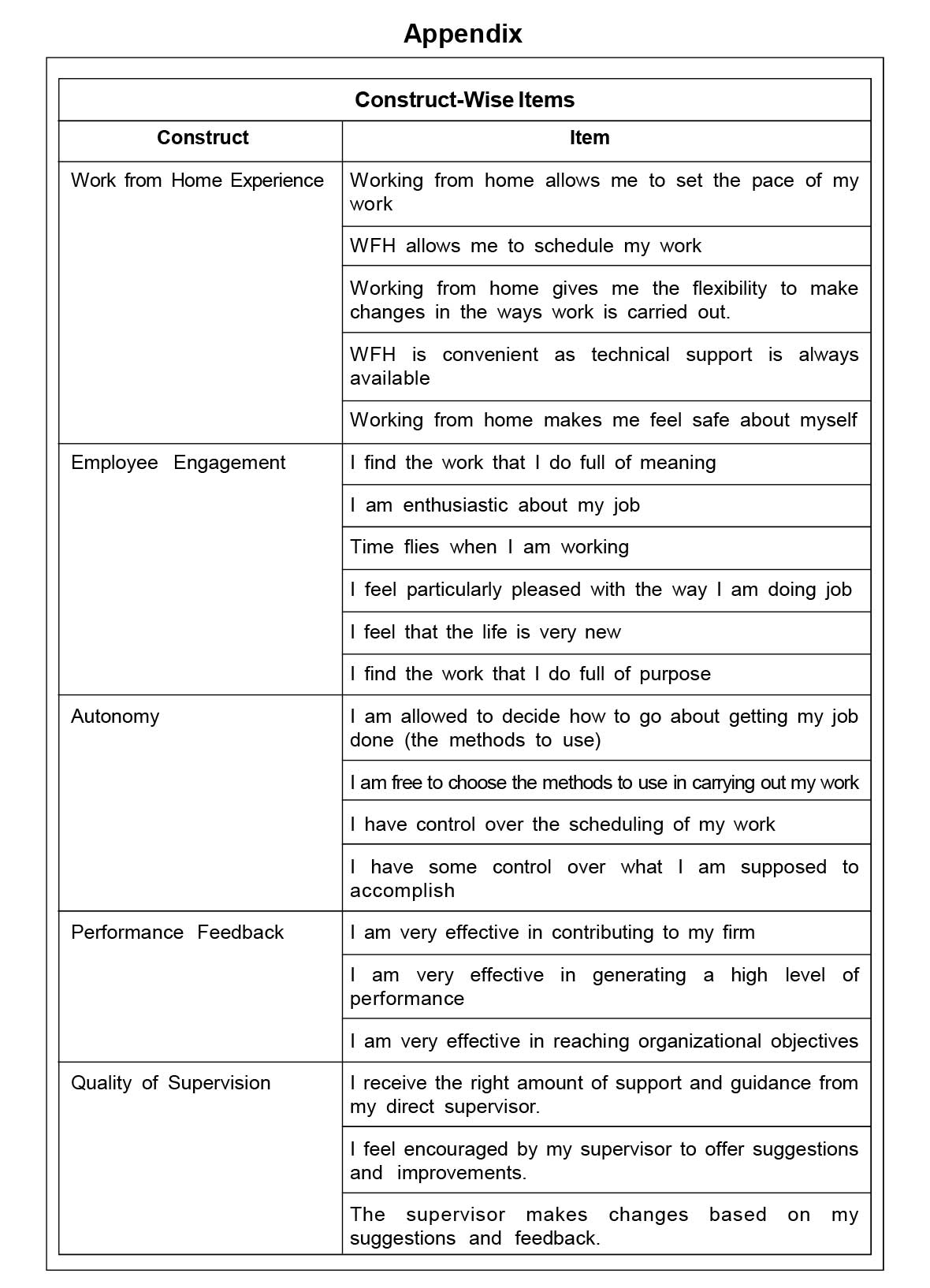

All the constructs together consist of 43 items. Construct-wise items are presented in Appendix.

The analysis is subdivided into two sections viz., measurement model and structural model. In the measurement model section, the researchers presented the validity (convergent and discriminant validity) of the constructs. On the other hand, in the structural model, the impact of WFH experience on employee engagement was tested.

Cronbach's alpha test was adopted to test the reliability of the questionnaire. The construct-wise alpha coefficient is presented in Table 3.

The constructs taken for the study were considered reliable as the alpha coefficients met the threshold value, i.e., 0.7 (Nunnally, 1976; and Robinson et al., 1991).

Exploratory Factor Analysis

According to Kaiser (1974), to test EFA, KMO and Bartlett test values should be within the limits of threshold, i.e., KMO should be above 0.5 and Bartlett test of sphericity must be below 0.05 (Field, 2013). The results of KMO and Bartlett's test show that the KMO value is high with 0.937, and Bartlett's test was also found significant, which validates that the data taken for the study is apt for factor analysis. For factor analysis, factors with eigen value of more than 1 were considered as significant. It is noted from the results that only 11 factors had eigen value of above 1.

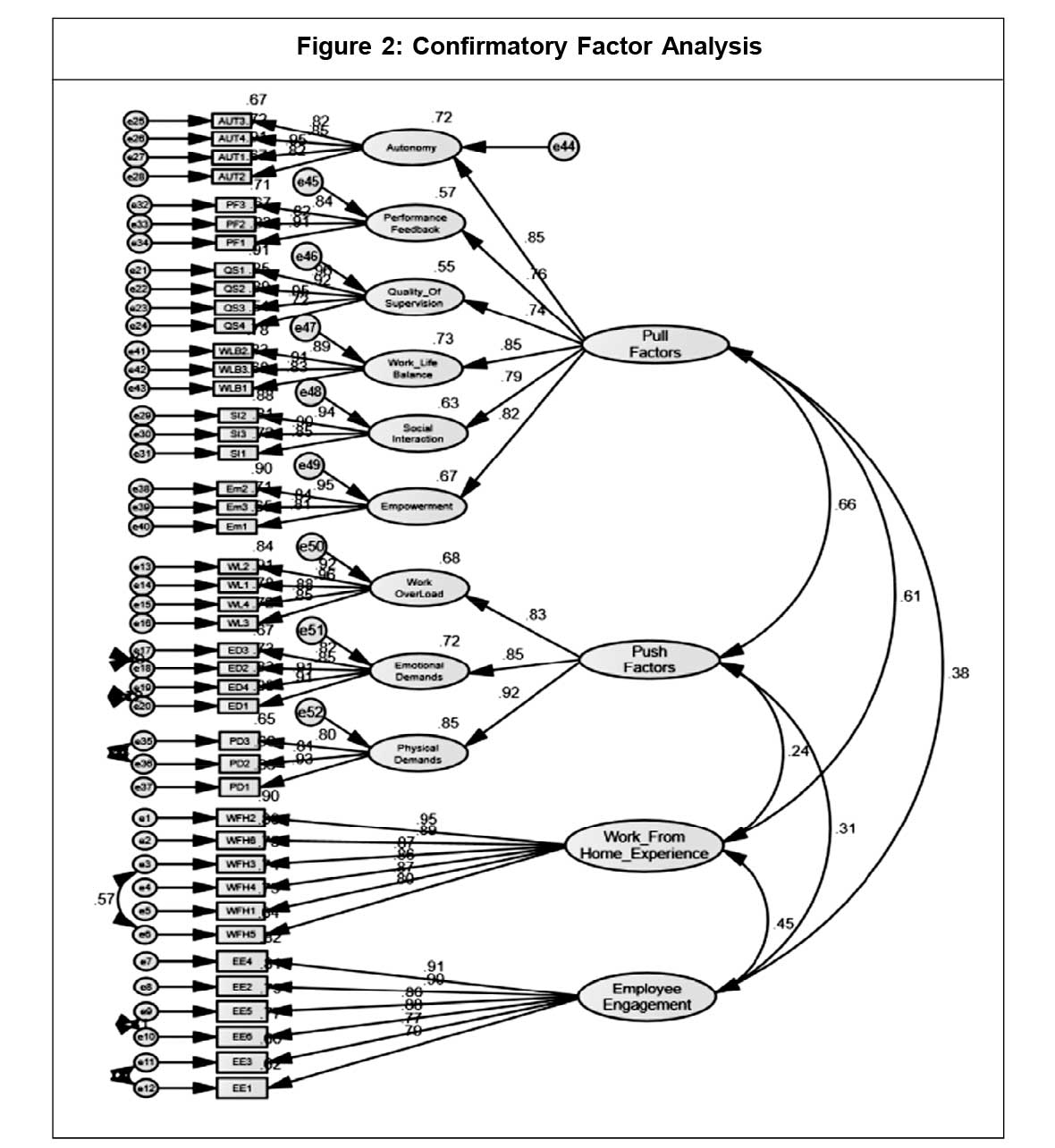

The rotated component matrix showed that eleven factors ( Autonomy, Performance feedback, Quality of supervision, Work-life balance, Social interaction, Empowerment, Work overload, Emotional demands, Physical demands, WFH experience and Employee engagement) were extracted from 43 items. To confirm antecedents in the model, a confirmatory factor analysis was done (Figure 2).

Measurement Model

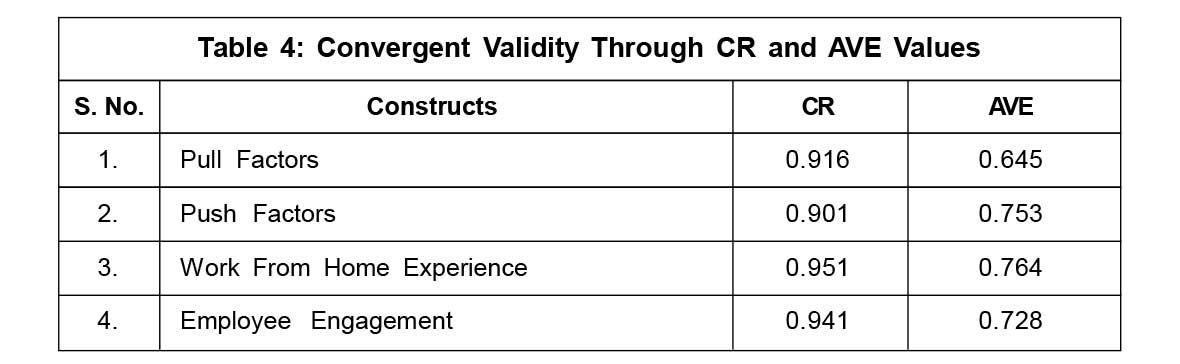

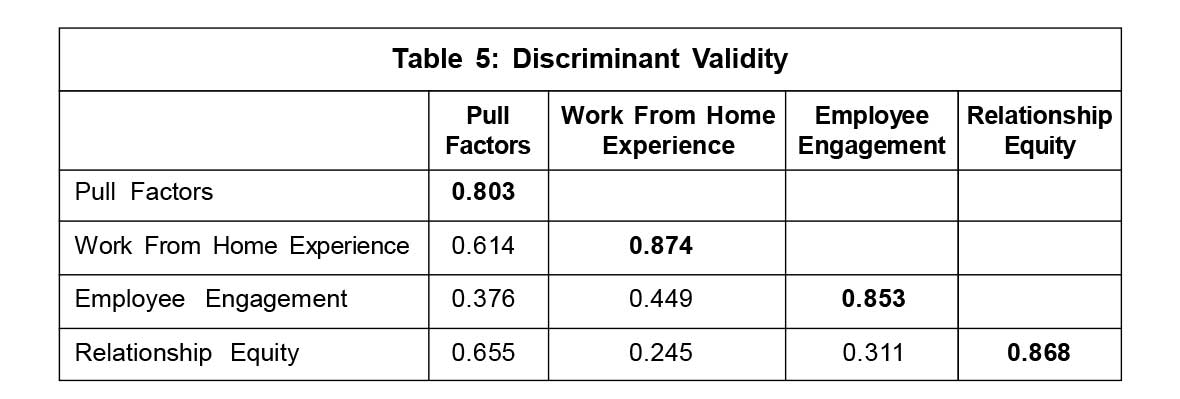

In order to prove model fit, both convergent and discriminant validity should meet the threshold values. The convergent validity explains how each item is related to its construct, whereas discriminant validity deals with the interrelationships among the constructs. Proving model fit in measurement model section is mandatory as it is a prerequisite for structural model.

It is a measurement model in which the latent variables can be observed based on indicator variables, and also reliability of the model can be tested. In the study, CFA is adopted to test the relationship between the factors and items (observed) and also to find out the linkage among the factors with reliability (Joreskog and Sorbom, 1989).

CFA was done on 43 items using principal component method to confirm the dimensionality of each construct. During CFA, it is noted that there is a high correlation among six constructs, viz., Autonomy, Performance Feedback, Quality of Supervision, Work-Life Balance, Social Interaction and Empowerment. Hence, these constructs were taken as second order constructs, i.e., Pull factors backed by literature support; similarly, another second order construct, i.e., Push factors formed with three latent constructs, viz., Work Overload, Emotional Demands and Physical Demands.

To test the validity of the four constructs in the study, viz., WFH experience, Employee Engagement, Push and Pull Factors, Confirmatory Factor Analysis was adopted. CFA consists of both zero order and second order constructs in the study.

Through CFA, it is observed that all the items of each of the four constructs perfectly met the threshold values (Hulland, 1999). Further, as part of validity testing, CR and AVE values are mentioned in Table 4.

The table shows the regression weights with respect to each construct with its respective CR and AVE values. It is noticed from the data that all the CR and AVE values met the threshold values (Nunnally and Bernstein, 1994; and Bagozzi and Yi, 1988). Hence, the convergent validity is proved. As the convergent validity was proved, the discriminant validity among the constructs was tested, which is presented in Table 5.

It is observed that all the diagonal elements which are square root of AVE are greater than its non-diagonal elements (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). Hence, the model does not suffer from any kind of validity issues.

All the model fit indices were noted to be above the threshold values. It is also observed that the values of GFI and AGFI are less than the threshold value, i.e., 0.8, but as the values are very near to 0.9, they can be considered (Baumgartner and Homburg, 1995; and Doll et al., 1994). Hence, the model is empirically fit.

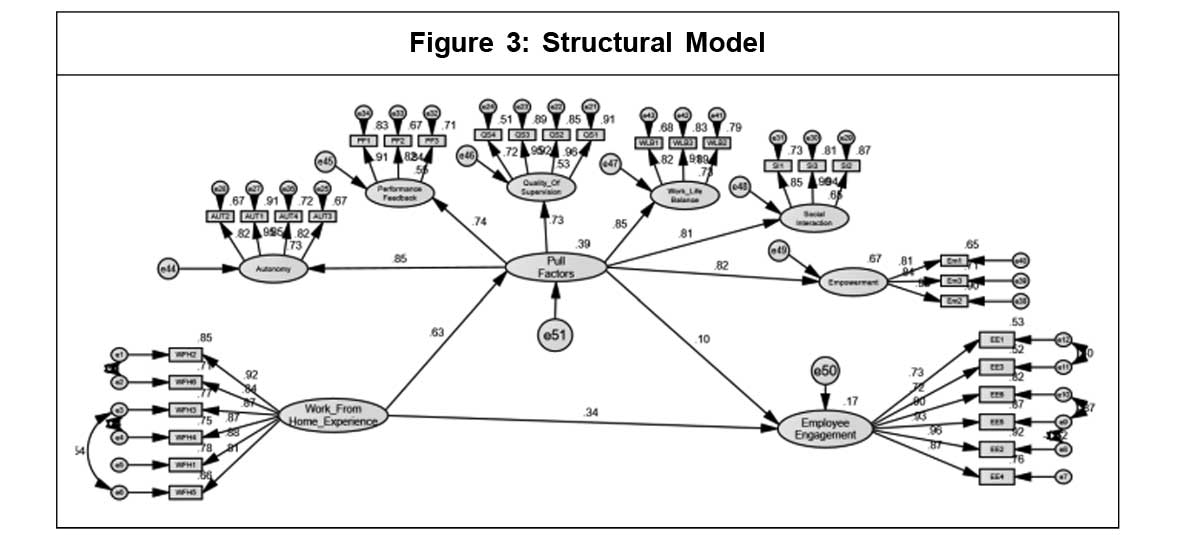

Structural Model

To estimate a series of dependence relationships among all constructs, structural model is tested. Three major constructs were taken for structural model, viz., 'WFH experience' (exogenous construct), 'Employee engagement' (endogenous construct) and 'pull factors' (mediating construct). The model is proposed to test the interrelationship among the constructs (WFH experience, employee engagement and pull factors). Based on the theoretical support, the effect of independent constructs on dependent constructs in the presence of one mediating construct, i.e., pull factors and one moderating construct, i.e., push factors, was examined in the structural model (Figure 3). The model fit indices for the structural model is presented in Table 6.

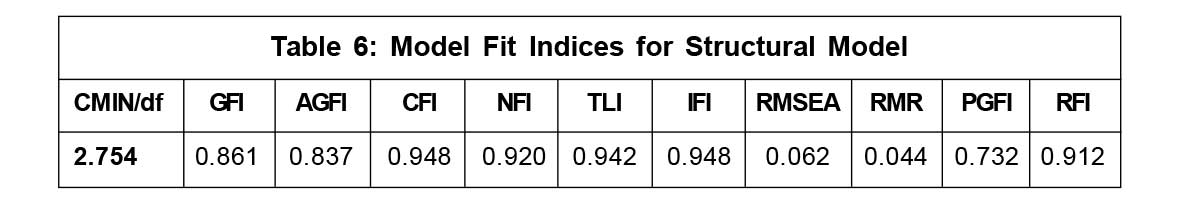

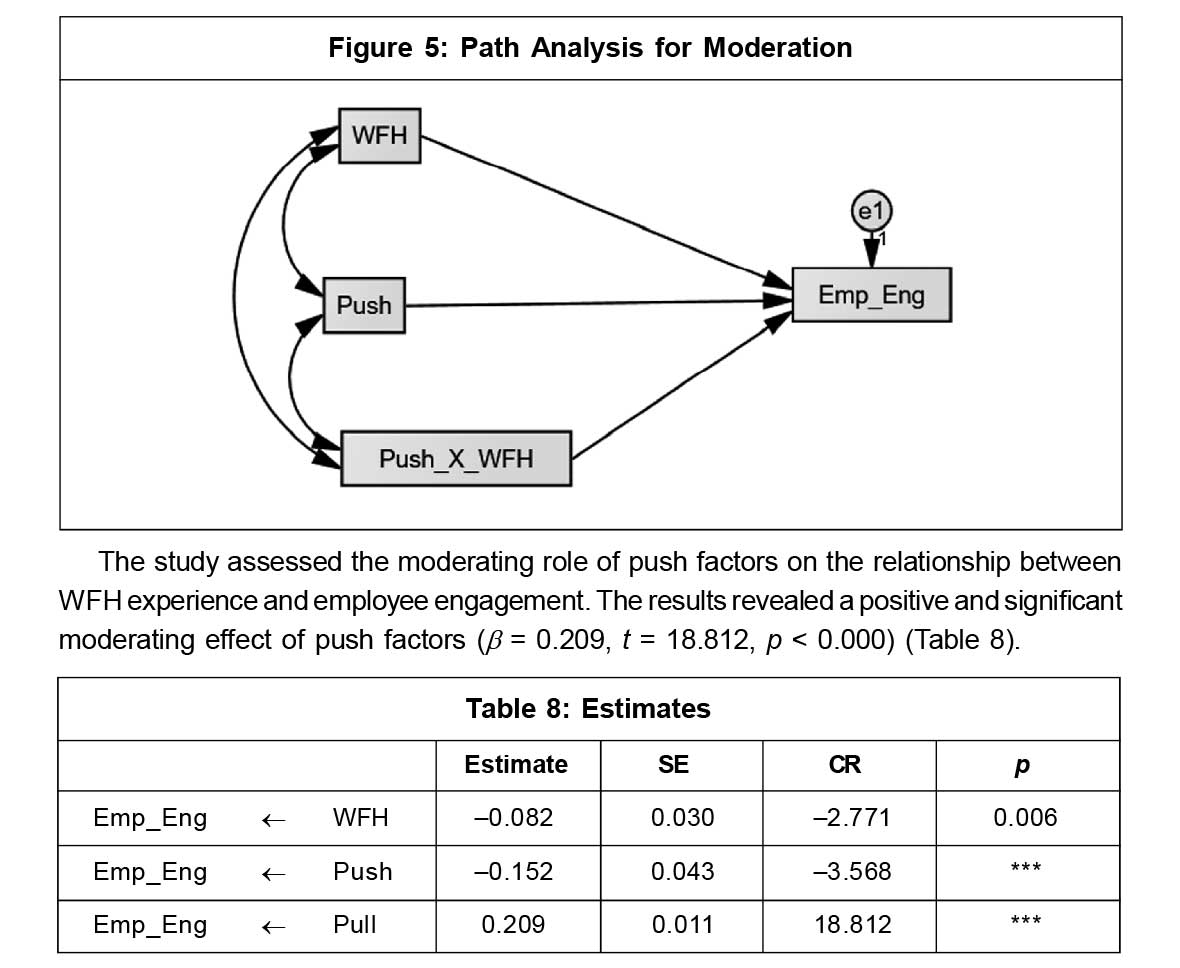

The model fit indices of the structural model met the threshold values. Hence, the structural model is empirically fit. The independent construct WFH experience had significant positive effect (b = 0.34, p = 0.001) on dependent construct, i.e., employee engagement. Apart from the model fit, the inter construct relationships were tested. The exogenous construct, i.e., 'WFH experience' is observed to have significant effect on endogenous construct, i.e., employee engagement. Further, the mediation effect of pull factors between WFH experience and employee engagement was examined through path analysis at three levels. At level 1, the impact of WFH experience (X) on employee engagement (Y) is measured in the absence of mediator and it is observed that X has a significant impact on Y (b = 0.47, p < 0.002).

At level 2, the impact of independent (X) on dependent (Y) is measured in the presence of mediating construct (M). It is noted that WFH experience (X) has significant effect on pull factors (M) (b = 0.63, p < 0.000) and that the pull factors (M) have significant effect on employee engagement (Y) (b = 0.10, p < 0.000). Hence, from this level 2, it is noted that the pull factors have a mediating role between WFH experience and employee engagement. As the direct effect (level 1) is significant, the mediation effect is considered as partial mediation effect. At level 3, the effect of X on Y is measured and observed as significant (b = 0.34, p < 0.000) in the presence of mediator (Table 7). The difference in beta coefficients at levels 1 and 3 depicts the effect of moderator, i.e., pull factors (Figure 4).

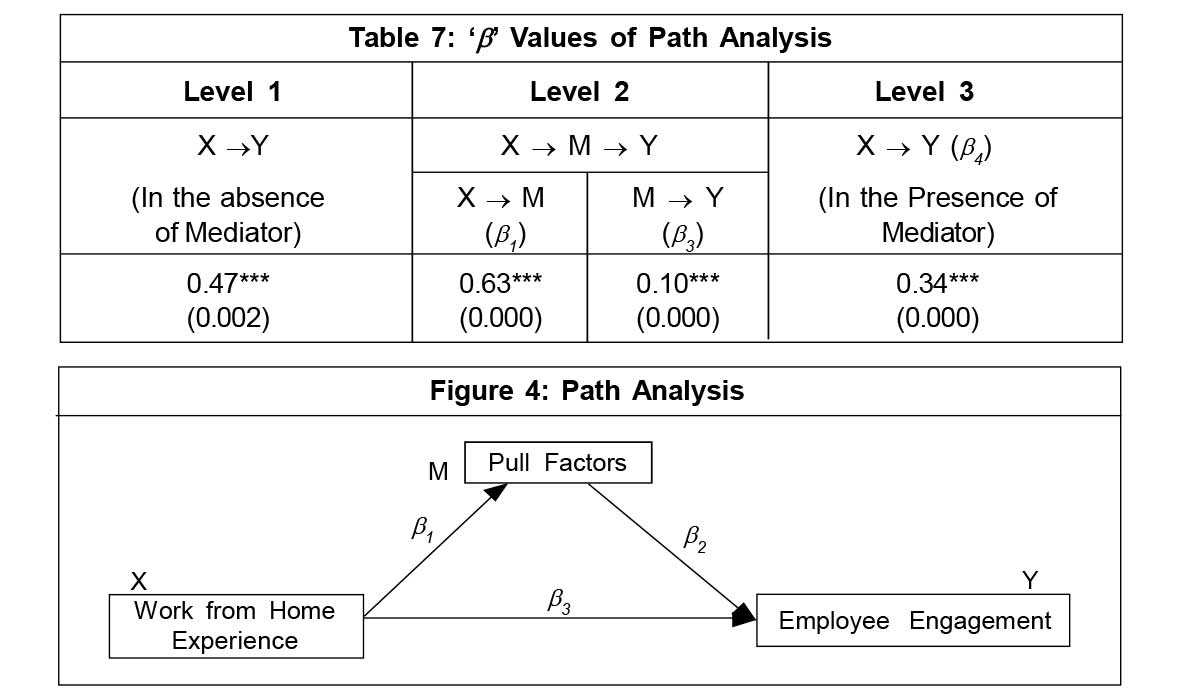

Moderation Analysis

Based on the literature review, the push factors were considered as the moderator in the model. The moderating effect of push factors on the relationship of WFH experience and employee engagement is tested. For testing, one interaction variable was taken, which is presented in Figure 5.

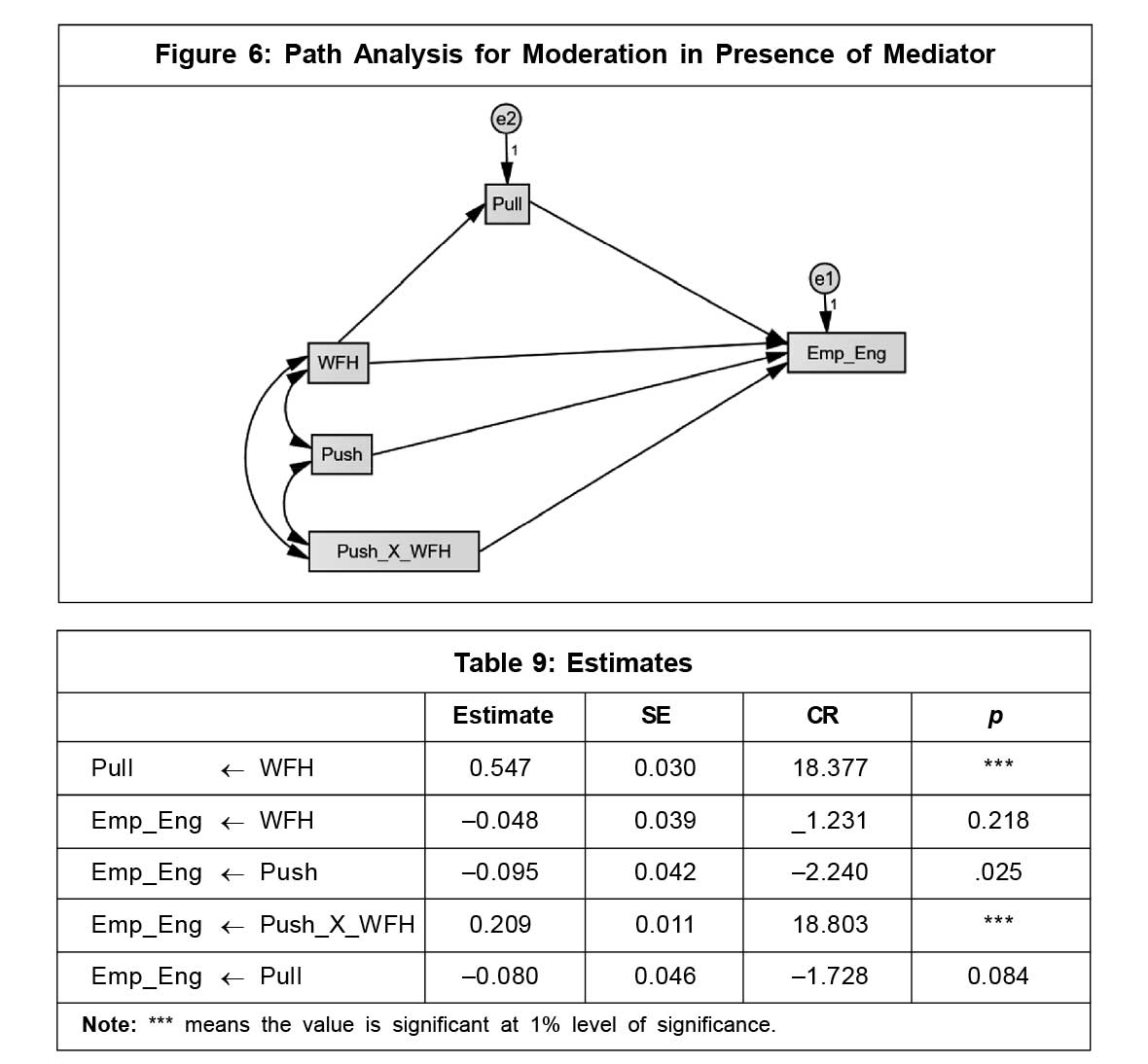

Moderation in the Presence of Mediator

Further, in the presence of moderator, i.e., push factor, the mediation appeared insignificant. Hence, it can be observed that push factors play a major role in employee engagement (Figure 6 and Table 9).

Hypothesis Testing

H1: WFH experience was considered as an independent construct and measured its effect on Employee Engagement (Dependent construct) of employees. It was found that the WFH had significant direct effect on the dependent variable with the regression coefficient 0.47 at 1% level of significant. Hence, the hypothesis is accepted.

H2: Second, the mediation effects of pull factors were measured on the relationship of independent and dependent constructs of the model. It was found that the pull factors proved to have partial mediation effect. It can also be noted that the direct effect of WFH on employee engagement has decreased from 0.47 to 0.34 in the presence of pull factors. Empirically, it is thus understood that WFH has more effect on employee engagement in the presence of mediator.

H3: Third, the moderation effects of push factors were measured on the relationship of independent and dependent constructs of the model. It was found that the push factors proved to have positive and significant moderation effect. Further, the direct effect of WFH on employee engagement was found to be significant at 1%. The same relationship was found to be insignificant in the presence of the moderator, i.e., push factors.

Discussion

The results indicate that all the items of WFH had an effect on employee engagement. Depending on the factors, the level of employee engagement would change in organizations. Hence, organizations that intend to allow their employees to WFH should be very cautious in designing the HR policies as it is empirically proved to have a direct effect on employee engagement.

In the relationship between WFH and Employee Engagement, factors like autonomy, performance feedback, quality of supervision, work-life balance, social interaction and empowerment play a vital role. Through mediation analysis by taking pull factors, it is found that WFH has a significant effect on employee engagement. The study thus suggests that for the successful implementation of WFH work culture, the pull factors should be offered to the employees. The pull factors are useful in formulating better strategies to elicit employee engagement.

In the relationship between WFH and Employee Engagement, work overload, emotional dependency and physical demands assume importance. Through moderation analysis by taking push factors, it is found that WFH has a significant negative effect on employee engagement. Hence, it is suggested to consider push factors in formulating strategies.

Conclusion

To conclude, the study confirmed that pull and push factors have an effect on employee engagement in the WFH context. Secondly, the objective was to find out the role of pull factors as a mediator between WFH experience and employee engagement. It is evident from the study that autonomy, performance feedback, quality of supervision, work-life balance, social interaction and empowerment have a mediating effect between WFH experience and employee engagement. The main intention was to test the moderating effect of push factors. In this instance, work overload, emotional demands and physical demands proved their moderating effect between WFH experience and employee engagement. The results show that there is a significant effect of push and pull factors on WFH experience and employee engagement.

Future Scope: In-depth exploration of antecedents of employee engagement would be more helpful. Further, researchers might consider other elements of push and pull in order to enhance the explanatory power of exogenous on endogenous variables.

- More methodological work is needed on how to capture the impact and outcomes of WFH towards employee engagement more robustly, including further analysis and exploration of impact.

- Furthermore, the researchers can consider the demographic factors as categorical moderators on the relationship between WFH and employee engagement to extract more accurate outcome.

References

- Abiddin N Z, Ibrahim I and Abdul Aziz S A (2022), "A Literature Review of Work From Home Phenomenon During COVID-19 Toward Employees' Performance and Quality of Life in Malaysia and Indonesia", Front. Psychol., Vol. 13, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.819860

- Ammons S K and Markham W T (2004), "Working at Home: Experiences of Skilled White-Collar Workers", Sociological Spectrum, Vol. 2004, No. 2, pp. 191-238.

- Aropah V D W and Sumertajaya I M (2020), "Factors Affecting Employee Performance During Work from Home", Int. Res. J. Bus. Stud., Vol. 13, No. 2, pp. 201-214. doi: 10.21632/irjbs.13.2.201-214.

- Bagozzi R P and Yi Y (1988), "On the Evaluation of Structural Equation Models", Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 16, No. 1, pp. 74-94, https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02723327

- Barrero J, Bloom N and Davis S (2021), "Why Working From Home Will Stick", Working Paper, Department of Economics, Stanford University.

- Baumgartner H and Homburg C (1996), "Applications of Structural Equation Modeling in Marketing and Consumer Research: A Review", International Journal of Research in Marketing, Vol. 13, No. 2, pp. 139-161. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-8116(95) 00038-0

- Bloom N, Liang J, Roberts J and Ying Z J (2013), "Does Working from Home Work? Evidence from a Chinese Experiment (2014), National Bureau of Economic Research, pp. 20-21.

- Bueiuniene I, Nakrosiene A and Gostautaite B (2019), "Working from Home: Characteristics and Outcomes of Telework", International Journal of Manpower, Vol. 40, No. 1, pp. 87-101.

- CoSo (2017), "CoSo Cloud Survey Shows Working Remotely Benefits Employers and Employees", February 17, 2015, https://www.cosocloud.com/press-releases/coso-survey-shows-working-remotelybenefits-employers-and-employees.

- De-la-Calle-Duran, M C, Rodriguez-Sanchez J L (2021), "Employee Engagement and Wellbeing in Times of Covid-19: A Proposal of the 5Cs Model", Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, Vol. 18, No. 10, p. 5470, https:// doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105470.

- Doll W J, Xia W and Torkzadeh G (1994), "A Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the End-User Computing Satisfaction Instrument", MIS Quarterly, Vol. 18, No. 4, pp. 453-461, https://doi.org/10.2307/249524

- Field A (2013), Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 4th Edition, Sage.

- Fonner K L and Roloff M E (2010), "Why Teleworkers are More Satisfied with Their Jobs than are Office-Based Workers: When Less Contact is Beneficial", Journal of Applied Communication Research, Vol. 38, No. 4, pp. 336-361.

- Fornell C and Larcker D F (1981), "Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error", Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 18, No. 1, p. 39, https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312

- Golden T D and Veiga J F (2008), "The Impact of Superior-Subordinate Relationships on the Commitment, Job Satisfaction, and Performance of Virtual Workers", The Leadership Quarterly, Vol. 19, No. 1, pp. 77-88.

- Gurstein P (2001), Wired to the World: Chained to the Home: Telework in Daily Life, UBC Press, Vancouver.

- Harpaz I (2002), "Advantages and Disadvantages of Telecommuting for the Individual, Organization and Society", Work Study, Vol. 51 No. 2, pp. 74-80.

- Hulland J (1999), "Use of Partial Least Squares (PLS) in Strategic Management Research: A Review of Four Recent Studies", Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 20, No. 2, pp. 195-204. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199902) 20:2<195::AID-SMJ13>3.0.CO;2-7

- Johnson L C, Audrey J and Shaw S M (2007), "Mr. Dithers Comes to Dinner: Telework and the Merging of Women's Work and Home Domains in Canada", Gender Place and Culture A Journal of Feminist Geography, Vol. 14, No. 2.

- Joreskog K G and Sorbom D (1989), LISREL7: A Guide to the Program and Applications, pp. 62-83, SPSS Publications, Chicago.

- Joubert M (2014), "A Comprehensive Engagement Predictive Model", Unpublished Doctoral Thesis, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa.

- Joubert M and Roodt G (2019), "Conceptualising and Measuring Employee Engagement as a Rolerelated, Multi-Level Construct", Acta Commercii, Vol. 19, No. 1, p. a605, https://doi.org/10.4102/ac.v19i1.605.

- Kaiser H F (1974), "An Index of Factorial Simplicity", Psychometrika, Vol. 39, No. 1, pp. 31-36, https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02291575

- Konrad T, Williams E, Linzer M and Care J M M (1999), "Measuring Physician Job Satisfaction in a Changing Workplace and a Challenging Environment", Medical Care, Vol. 37, No. 11, pp. 1174-1182. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/3767071

- Lichtenstein R (1984), "Measuring the Job Satisfaction of Physicians in Organized Settings", Medical Care, Vol. 22, No. 1, pp. 56-68.

- Mehta P (2021), "Work from Home - Work Engagement Amid Covid-19 Lockdown and Employee Happiness", Journal of Public Affairs, Vol. 21, No. 4, p. e2709

- Morgan R E (2004), "Teleworking: An Assessment of the Benefits and Challenges", European Business Review, Vol. 16 No. 4, pp. 344-357.

- Nunnally Jum C (1976), Psychometric Theory, p. 640, McGraw Hill, New York.

- Nunnally J C and Bernstein I H (1994), Psychometric Theory, 3rd Edition, McGraw Hill, New York.

- Pejtersen J H, Kristensen T S, Borg V and Bjorner J B (2010), "The Second Version of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire", Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, Vol. 38, No. 3, pp. 8-24, https://doi.org/10. 1177/1403494809349858.

- Pratt J H (1999), "Selected Communications Variables and Telecommuting Participation Decisions: Data from Telecommuting Workers", The Journal of Business Communication, Vol. 36 No. 3, pp. 247-254.

- Qureshi I, Jamil R, Iftikhar M et al. (2012), "Job Stress, Workload, Environment and Employees Turnover Intentions: Destiny or Choice", Archives of Sciences (Sciences Des Archives), Vol. 65, No. 8, pp. 230-241.

- Robinson J P, Shaver P R and Wrightsman L S (1991), "Criteria for Scale Selection and Evaluation", Measures of Personality and Social Psychological Attitudes, pp. 1-16, Academic Press, https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-590241-0.50005-8

- Saks A M (2006), "Antecedents and Consequences of Employee Engagement", Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 21, No. 7, pp. 600-619.

- Saragih Susanti (2011), "The Effects of Job Autonomy on Work Outcomes: Self Efficacy as an Intervening Variable", International Research Journal of Business Studies, Vol. 4, No. 3, pp. 203-215. 10.21632/irjbs.4.3.203-215.

- Seppala P, Mauno S, Feldt T et al. (2009), "The Construct Validity of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale: Multisample and Longitudinal Evidence", Journal of Happiness Studies, Vol. 10, No. 4, pp. 459-481, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902- 008-9100-y.

- Shiu E, Hair J, Bush R and Ortinau D (2009), Marketing Research, 1st Edition, McGraw-Hill Education, Berkshire.

- Sinha Deepti (2016), "Study of Emotional Intelligence Amongst the Employees of Service Sector", International Journal of Global Management, Vol. 6, pp. 32-40.

- Sridevi R (2021), "A Study on the Impacts of Work from Home Among IT Employees", Utkal Historical Research Journal, Vol. 24, pp. 469-482.

- Stevenson B and Wolfers J (2009), "The Paradox of Declining Female Happiness", American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, Vol. 1, No. 2, pp. 190-225.

- Stockwell D R and Peterson A T (2002), "Effects of Sample Size on Accuracy of Species Distribution Models", Ecological Modelling, Vol. 148, No. 1, pp. 1-13.

- Tremblay D G and Thomsin L (2012), "Telework and Mobile Working: Analysis of its Benefits and Drawbacks", International Journal of Work Innovation, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 100-113.

- Tunk N and Kumar A A (2022), "Work from Home-A New Virtual Reality", Current Psychology, pp. 1-13, doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02660-0

- Umapathi P and Mounika A (2022), "Remote Work: A Paradigm Shift of Working Culture in IT Industry", Madhya Bharti, Vol. 82, No. 14, pp. 213-218.

- Venkatesh V, Thong Y L and Xu X (2012), "Consumer Acceptance and Use of Information Technology: Extending the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology", MIS Quarterly, Vol. 36, No. 1, pp. 157-178.

- Wang B, Liu Y, Qian J and Parker S K (2021), "Achieving Effective Remote Working During the Covid-19 Pandemic: A Work Design Perspective", Appl. Psychol., Vol. 70, No. 1, pp. 16-59. doi: 10.1111/apps.12290.

- Wong K K K (2013), "Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Techniques Using SmartPLS", Marketing Bulletin, Vol. 24, No. 1, pp. 1-32.