July '21

The IUP Journal of Organizational Behavior

Archives

The Influence of Family-Supportive Organization Perception and Work-Family Conflict on Absenteeism: The Mediating Role of Work Engagement

Thangavadivel Roshan

Research Student, Department of Management, Faculty of Commerce and Management in Eastern

University, Vantharumoolai, Chenkalady, Batticaloa, Sri Lanka; and is the corresponding author.

E-mail: idofmr@gmail.com

Anthonypillai Anton Arulrajah

Head, Department of Management, Faculty of Commerce and Management in Eastern University, Vantharumoolai, Chenkalady, Batticaloa, Sri Lanka. E-mail: aantonarulrajah@yahoo.com

Employees are the crucial asset of an organization, especially in the apparel sector, as they directly influence operations and organizational performance. The present study was conducted with the aim of investigating the reasons for the unscheduled absenteeism and the influence of Family-Supportive Organization Perception (FSOP) and Work-Family Conflict (WFC) on work engagement and absenteeism of a selected apparel sector firm's machine operators. The primary data was collected through self-administrated surveys from 155 machine operators, and among those respondents, semi-structured interviews were conducted with 50 machine operators. The study revealed that family responsibilities, health issues, society and cultural factors, workplace-related factors, behavioral/personal factors, and general factors are the causes for unscheduled absenteeism. FSOP, WFC, and work engagement have resulted in high levels, and absenteeism has resulted in low levels as per the results of the study. There is a significant and moderately negative relationship between FSOP and absenteeism, work engagement and absenteeism, WFC and work engagement, and there is a significant and moderately positive relationship between WFC and absenteeism, and FSOP and work engagement. Further, work engagement partially mediates the relationship between FSOP and absenteeism, and WFC and absenteeism. The findings of the study have various managerial implications for other apparel manufacturing firms.

Introduction

Employees are the cornerstone of every organization. The better they are, the better qualified, prepared, managed, effective, and profitable the organization will be. Sri Lanka provides high-quality garments in a reliable way than other competitor countries like China and India. The primary strengths of the Sri Lankan clothing industry are exceptionally proficient labor force, vital strategic area, great framework, output quality, and advancement in quick solutions (Derasinghe, 2017). The recent trends in the worldwide clothing industry with the aim of greater productivity and cost reductions become another difficult factor in the clothing industry in Sri Lanka (Ranaweera, 2014). Worker turnover and increasing absenteeism are currently becoming hurdles in the clothing industry, leading to failure to attain the objectives

(Abdur and Atm, 2015).

The basic concern of human asset management is to deliver and retain a fulfilled labor force which helps in achieving organizational goals. Employees failing to participate in their duties without prior approval is a normal condition in every organization. Some are absent from work more than others, however, when it happens all the time and by most of the workers, then it is a matter of concern for the organization. The absence of dedication in coming to work or not informing in advance shows an absence of organizational commitment. It brings down efficiency and effectiveness of the organization because of the workers' unexpected non-attendance (Edwards and Greasley, 2010). Kelagama and Epaarachchi (2003) discovered that one of the most critical variables influencing the intensity of the Sri Lankan clothing industry is low efficiency. The reasons for low efficiency as indicated by Kelagama and Epaarachchi (2003) are poor working conditions, lack of employee commitment, high labor turnover and absenteeism, inadequate human resource development, strained employer-employee dialogue, restrictive labor regulations, and poor incentives for workers.

Demographic changes with the inclusion and expansion in the number of women workforce, dual-career families, and single-parent families have created an increasingly diverse workforce requiring workers to balance work and family. Across countries and occupations, it is still mainly women who are more responsible for family-related issues and duties, and who, ordinarily regardless of hours worked in paid business, work a 'second shift' at home (Galinsky et al., 2008a). Work-Family Conflict (WFC) can have a huge negative effect on the working and well-being of individual employees, families, organizations, and societies (Hassan et al., 2010).

Numerous associations offer policies and benefits to assist workers to manage work and family (Galinsky et al., 2008b). Therefore, policies are important, however, perceptions of organizational support for workers' families might be more important (Allen, 2001). Research has shown that when workers see their organization and supervisors as more family-supportive, they report less work-life struggle, lesser turnover intentions, lower level of absenteeism, and less employment burnout as well as more job satisfaction and full commitment (Cook, 2009).

Employers have gone the additional mile of giving an option for workers to telecommute and numerous measures have been taken to retain workers. Flexibility in working hours and innovative thoughts for making workers feel engaged with the organization have become a significant criterion in Human Resource Management (HRM). Organizational productivity is determined by the involvement and effort of work by the workers (Musgrove et al., 2014). The study stated the workers who are engaged consistently demonstrated more productivity, more security and tend to stay in the organization (Ahuja and Modi, 2015). Worker engagement is nowadays the focal point of HRM and a significant part of high-performance work practices (Attridge, 2009). Schaufeli (2013) stressed that the endurance of organizations is profoundly dependent on workers with advanced mental abilities. He viewed engagement as a desirable condition for workers and a basic driver of successful companies working in a highly competitive environment.

Currently, apparel firms have understood the significance of the absentee behavior of their employees, employee engagement, and top management is attempting to set up strategies to enhance work engagement and to reduce unscheduled absenteeism of their workers. Hence, it is important to consider unscheduled absenteeism and the influencers of unscheduled absenteeism. Further, there is an empirical knowledge gap in the Sri Lankan apparel sector of the direct influence of FSOP, WFC on absenteeism and the indirect effect of these variables on absenteeism via work engagement.

Literature Review and Hypotheses Formulation

Family-Supportive Organization Perception

Allen (2001) presented the idea of FSOP and it refers to how much workers see their organization as supportive of their family-related responsibilities and also personal needs (i.e., resources that can be freely accessed by employees to effectively manage work and family demands (Allen, 2001)). FSOP consists of providing emotional support, instrumental support, and developing creative solutions to work-family management challenges (Hammer et al., 2013). To ensure workers manage work and personal responsibilities, the role of family support has been shown to have positive effects on employees (Kossek et al., 2011). Russo et al. (2015) found that people without family backing may encounter expanded mental affliction, terrible temper, and depletion of assets while accomplishing jobs, failing to accomplish satisfactory work-life balance, especially in the apparel context.

Work-Family Conflict

Studies on the work-family interface has expanded over the past years, changes and shifts in demographics (more dual-worker or dual-career couples and single-parent families) and working states (more job uncertainty and more blurring of boundaries between life and work) are making the employees unable to handle demands and tasks from both work and family areas effectively (Ghislieri and Colombo, 2014). Bethge and Borngraber (2015) identified WFC as a formation of inter-role strife in which the responsibilities from work and family space are mutually inconsistent in some way, that is, participation in one role can produce more difficulty in effectively participating in other roles. Conflicting demands from work and family drain an individual both physically and psychologically, and those demands of roles from one domain often can pose a challenge to performing at full capacity in the other domain (Bellavia and Frone, 2005). Shaw (2010) found that female workers of the clothing industry experience negative effects of WFC because of long duty hours, substantial responsibility per individual and high pressure because of target inclusion, request satisfaction and inflexible working plans. Women harassment, WFC and child labor force have become major issues in the Bangladesh clothing industry (Ullah and Rahman, 2013). In Cambodia, lack of training, education, and WFC have become a limitation to worker's productivity in the clothing industry (Natsuda et al., 2010). In Sri Lanka, the WFC and poor job satisfaction have led to labor unrest situations (Thatshayini and Rajini, 2018).

Work Engagement

Engagement at work was conceptualized by Kahn (1990, p. 694) as "the physical, mental, and emotional involvement of employees themselves towards their duties and performance." Arokiasamy and Tat (2019) identified that engaged employees show superior performance and productive behavior and that those workers are more willing to go beyond the duties allocated to them. Workers who highly engage with their work schedule experience a strong relationship with their organization and this engagement can be recognized by energetic work behaviors (vigor), commitment to work (dedication), and great involvement with the work (absorption) (Bakker, 2017). Disengaged workers isolate themselves from their jobs and discontinue their involvement in their work and it could prompt high turnover intention and absenteeism (Kumara and Fasana, 2018). As Golden (2011) stated, married female workers in the clothing industry were less dedicated and not actually engaged in their work because of guilty feeling and the feeling of regret for not investing as much energy as they ought with their kids and relatives. Gallup (2013) stated that work units that are in the first 25% of their Q12 apparel workers database have impressively had greater productivity, fewer turnover and absenteeism, and fewer wellbeing/safety occurrences than those in the bottom 25%. So they referenced engaged workers as the backbone of their organization. Additionally, they recognized worker's engagement emphatically influences worker's work and family lives.

Absenteeism

Absenteeism comes from the Latin word "absentia" referring to the nonattendance status of the workers (Cikes et al., 2018). As indicated by Kinnear et al. (2006), the term "absenteeism" refers to unapproved and unscheduled absence of a worker from his/her workplace. Kinnear et al. (2006) stated that there are two kinds of absenteeism - culpable and non-culpable. Non-culpable absenteeism refers to an employee's authorized leave or absenteeism and there is no charge or penalty for that such as annual leave quota, sickness leave, paternity, and maternity leaves. Culpable absenteeism means unauthorized and non-allowed absenteeism of the employees (Kocakulah, 2016). Unauthorized absenteeism has been recognized as a huge management obstacle for the organization and the poor performance measure for workers within the organization (Raja, 2019). Worker absenteeism is seen as a costly situation to the organizations and the whole economy in terms of loss of productivity (Martin, 2017). As a critical organizational component, employee equality and respect are crucial because of the HR issues like increased turnover, high absenteeism, and these issues presently have become huge barriers to accomplish the business objectives in the clothing industry (Kottawatta, 2013). Robbins and Judge (2004) stated that organizations that depend heavily on assembly-line production, especially apparel sectors, are at risk of interruption from above-average absenteeism rates (higher than 3%), as the expenses related with absenteeism will eventually bring about delayed decision-making, stressed relations with clients because of poor quality and late deliveries. Hence, organizations should take measures to keep absenteeism from turning into a burden.

Relationship Between FSOP and Absenteeism

Organizations that support family accept that such contribution helps increase recruiting potential, assurance, profitability, quality, and diminishes absenteeism, late reporting, accident rates, turnover, and worker's pressure (Haar and Roche, 2010). Researchers have connected supervisory family support to favorable work results, including work fulfillment, lower turnover, and increased attendance (Kossek, 2005; and Cook, 2009). Research has shown that FSOP explains unique variance in work fulfillment, attendance motivation, and turnover expectations (Carlivati, 2007). FSOP has been connected to diminished turnover aims, occupation burnout, and expanded employment fulfillment, life fulfillment, and attendance motivation (Kossek et al., 2011). According to the Social Exchange theory, workers may spend their own resources, for instance, in terms of time and priority to pay the organization back as an exchange for the family support by actively participating in the scheduled work without being absent. Hence, the following hypothesis is postulated:

H1: There is a negative relationship between FSOP and absenteeism.

Relationship Between FSOP and Work Engagement

Work-family practices such as flexible work schedules, work from home and childcare assistance have promoted increased recruitment, maintenance of qualified staff, and greater employee engagement (Carlivati, 2007). Further, in an examination of 623 data innovation laborers, family-supportive supervisor behaviors were seen as positively related to employee well-being and engagement (Matthews et al., 2014). Family-supportive supervisor behavior contributes to creating and holding people's emotional, intellectual, and physical assets, which would then be able to coordinate with expanding their engagement (Hammer et al., 2015). Research has reliably shown that the view of family-supportive supervision and family-friendly organizations help cultivate a strong work-family culture, promote mental and physical well being and upgrade positive business-related results such as engagement, work fulfillment, and commitment (Kossek et al., 2011). Moreover, family support is one of the job resources according to the Job demands-resources model theory; therefore, when there are more job resources, it can have a positive influence on work engagement. Therefore, it is hypothesized that:

H2: There is a positive relationship between FSOP and work engagement.

Relationship Between Work Engagement and Absenteeism

Engaged workers consistently have better attendance records and remain for a longer period of time in an organization in contrast to non-engaged workers (Attridge, 2009). As per Ahuja and Modi (2015), voluntary absenteeism rather than involuntary absenteeism from work may reflect work disappointment and absence of engagement. The research outcomes uncovered that engagement is negatively identified organization's recorded absenteeism days for support service laborers in the United Kingdom (Soane et al., 2013), self-report absenteeism days of coworkers of a Dutch police organization (Brummelhuis et al., 2010), and the number of an organization-registered non-attendance and absenteeism days of telecom supervisors in the Netherlands (Schaufeli et al., 2009). Hence, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3: There is a negative relationship between work engagement and absenteeism.

Relationship Between WFC and Absenteeism

Research has found work-life balance to be positively related to individual and organizational results, such as the organization's financial performance and worker fulfillment, work profitability, organizational commitment, and attendance motivation (Wang and Walumbwa, 2007). Employees' capacity to accomplish work-life balance with their organizational help should prompt higher employee commitment, engagement, and reduce turnover intentions, absentee behaviors (Bhalerao, 2013). Obligations at work can conflict with obligations at home, and these struggles lead to pressure, depression, and ultimately absenteeism (Shekhar, 2016). Further, as per the job demands-resources model theory, WFC is a job demand that leads to burnout and ultimately promotes health issues and depression. These consequences also can be the root cause behind absenteeism. Hence, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4: There is a positive relationship between WFC and absenteeism.

Relationship Between WFC and Work Engagement

Research study by Mohd et al. (2016) stated that the elements that can impact employee engagement are reward, work condition, and work-life balance. As indicated by Osario et al. (2015), work-life balance has a role in increasing work engagement. Workers who experience conflicts between their work and private lives are probably going to encounter negative feelings and perspectives such as lack of engagement and commitment (Shankar and Bhatnagar, 2010). Bedarkar and Pandita (2014) likewise showed a solid connection between WFC, worker engagement, and retention. These days, the corporate world is exceptionally centered on giving ideal work-life balance approaches to upgrading workers' maintenance, engagement, commitment, work fulfillment, and psychological wellness or efficiency (Shekhar, 2016). Moreover, the Job demands-resources model theory illustrated this negative impact as when there is high job demand (WFC), it will ultimately have a negative impact on worker's work engagement and commitment. Therefore, this study examines the hypothesis:

H5: There is a negative relationship between WFC and work engagement.

The Mediating Role of Work Engagement

Past research has indicated that workers who find that their organization is less responsive to their family needs would be less engaged in work and organization, and subsequently may leave the organization (Wang and Walumbwa, 2007). Work-family policies such as adaptable work schedules and childcare assistance have enhanced job satisfaction, commitment, engagement, and ultimately it leads to improving worker's behaviors like motivation and regular attendance (Carlivati, 2007). Organizations formulate family-friendly policies and strategies in order to improve affective commitment, improve employee wellbeing, and employee engagement which are having positive results by diminishing worker's turnover intentions, absenteeism, early departure, and lack of satisfaction (Kossek et al., 2011).

Without work-life balance in an organization, engagement will be more difficult to accomplish and this will, in the end, increase the turnover intention and absenteeism (Saeed et al., 2013). Worker's ability to strike a balance between work and family with their employer's support can increase employee commitment, engagement, and therefore lead to reduced turnover intentions and absentee behaviors (Bhalerao, 2013). Research has indicated that engagement can be achieved by job satisfaction, work-life balance, healthy workplace, and level of engagement decides workers' efficiency, attendance motivation, and desire to stay in the organization (Myilswamy and Gayatri, 2014). Hence, this review proposes the hypotheses as:

H6: Work engagement mediates the relationship between FSOP and absenteeism.

H7: Work engagement mediates the relationship between WFC and absenteeism.

Conceptual Framework

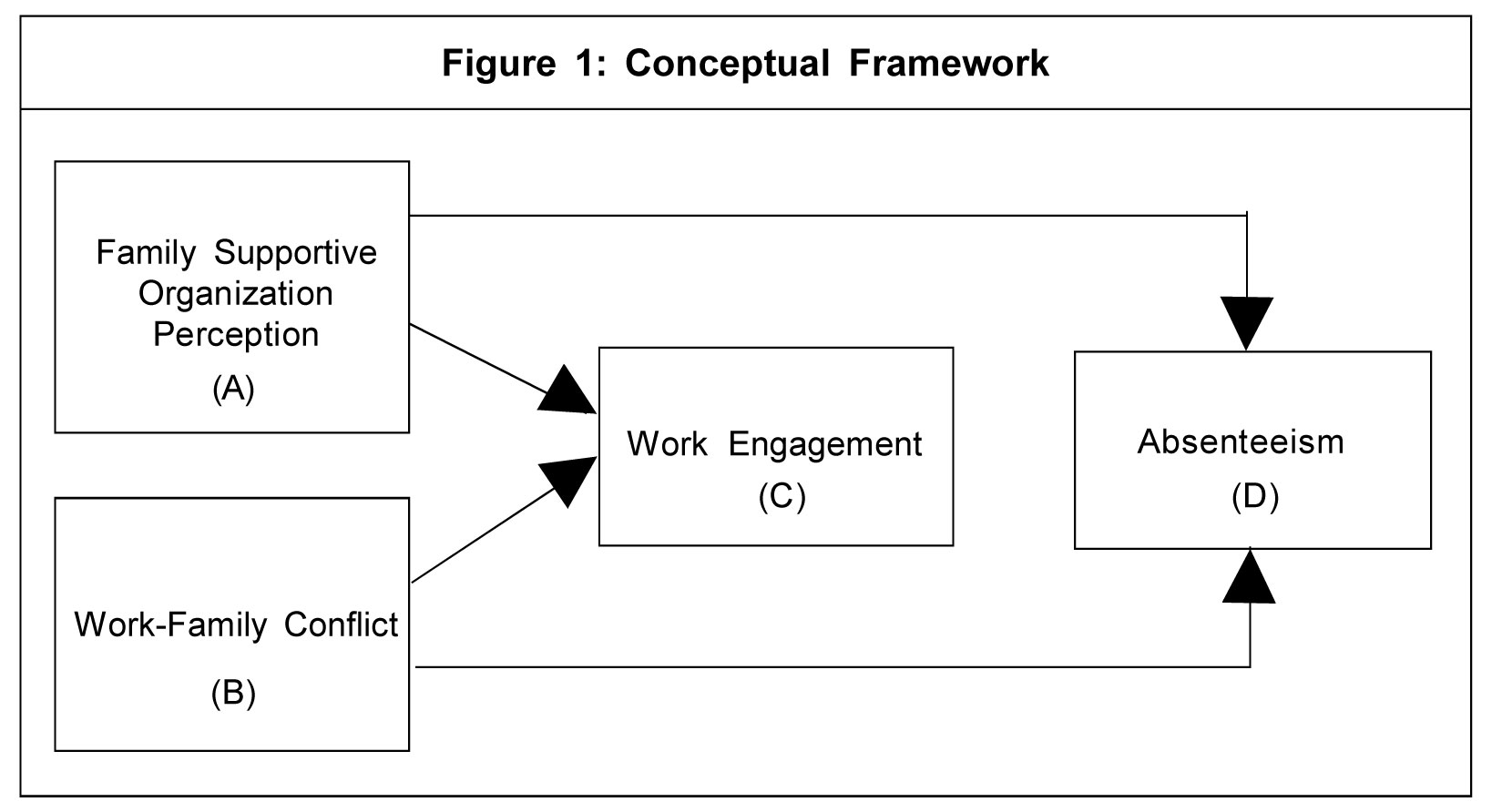

There are theories to hold up the conceptual framework of this study, such as Spillover theory, Social exchange theory, and Job demand-resource model. Spillover concerns the transmission of state of well-being from one domain of life to another (Westman, 2002). Conceptualization of Spillover theory holds that there are no boundaries between work and family life (Zedeck and Mosier, 1990). This theory suggests that when individuals feel stressed in one role, that stress influences functioning in the other role and can affect one's behavior (Bragger et al., 2005). Social exchange theory is the most influential conceptual paradigms for understanding workplace behavior (Cropanzano and Mitchell, 2005). The social exchange process begins when an organization treats a target individual (employees/employee's families) in a positive or negative fashion (Eisenberger et al., 2004). Social exchange theory predicts that in reaction to positively initiating actions, targets will tend to reply in kind by engaging in more positive and reciprocating responses and/or fewer negative reciprocating responses (Gouldner, 1960).

Schaufeli and Bakker (2004) introduced a revised version of the JD-R model. Job demands and job resources were identified as possible antecedents of burnout and work engagement. Demerouti et al. (2001) characterized job demands as the physical, social, and organizational parts of the activity that require continued physical and/or mental exertion. Job resources were characterized as those physical, social, and organizational parts of the activity that can be functional in accomplishing work objectives or decrease work requests and the related physiological and mental exertions, and stimulate self-improvement and advancement (Demerouti et al., 2001). Burnout is expected to intercede the connection between job demands and work engagement. Workplaces that offer numerous resources cultivate employee's willingness to commit their efforts and capabilities to the work tasks.

Based on the literature and theories, this study conceptualizes the framework for investigating the relationships between the variables (independent and dependent) and the mediating role of work engagement (Figure 1).

Objective

The objective of the study is to investigate the reasons for unscheduled absenteeism, assess the levels of FSOP, WFC, work engagement and absenteeism, identify the relationship among those variables, and investigate the effect of FSOP, WFC on work engagement and absenteeism of the selected apparel sector firm.

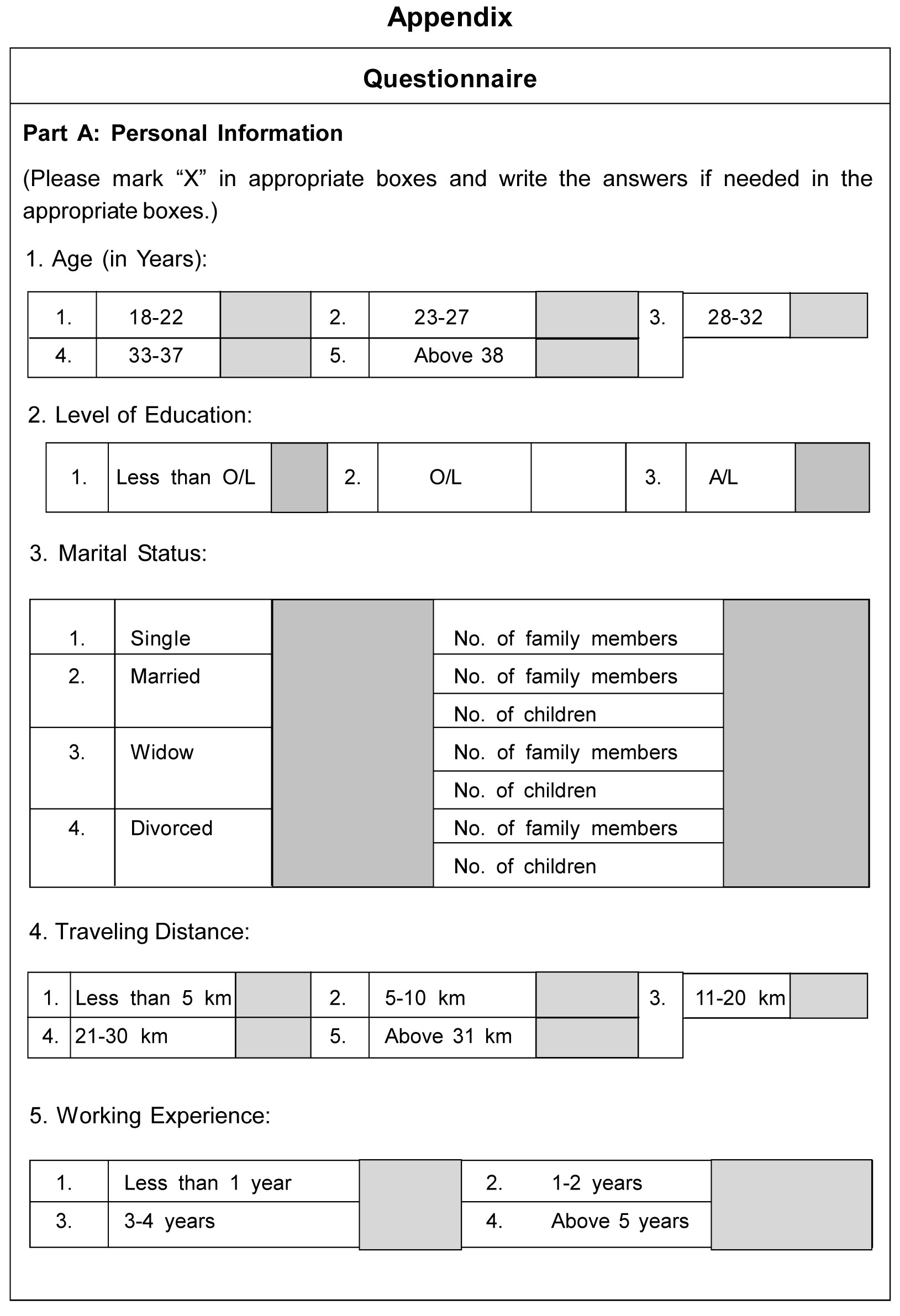

Data and Methodology

The data was collected through a self-administrated questionnaire (Part I - Respondents' personal information and Part II - Study variables), and semi-structured interviews in a leading apparel firm in Batticaloa District of Sri Lanka, where all the machines operators are only women. The self-administrated questionnaires were distributed randomly among 155 machine operators, and among those respondents, 50 machine operators were randomly selected to conduct the semi-structured interviews. The sample size was generated through the method of simple random sampling. It has been noted that a majority of the respondents are under the age group of 23-27 years (37.4%), without Ordinary Level (O/L) qualification (60.6%), married (56.8%), with 4-6 family members (73.5%), having 1-2 children (47.7%), reside less than 5 km from the workplace (39.4%), and with 3-4 years of work experience (44.5%).

Measures

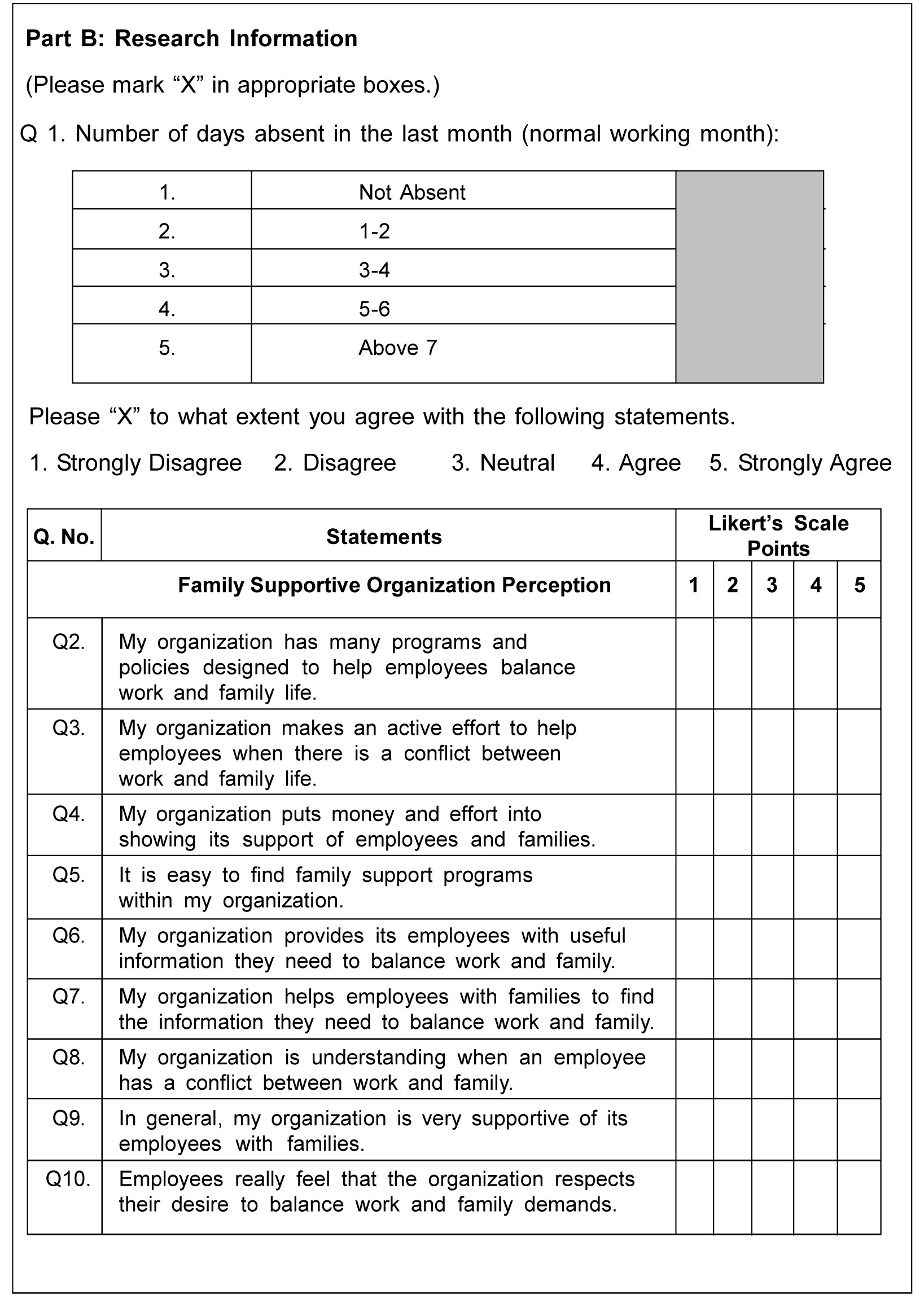

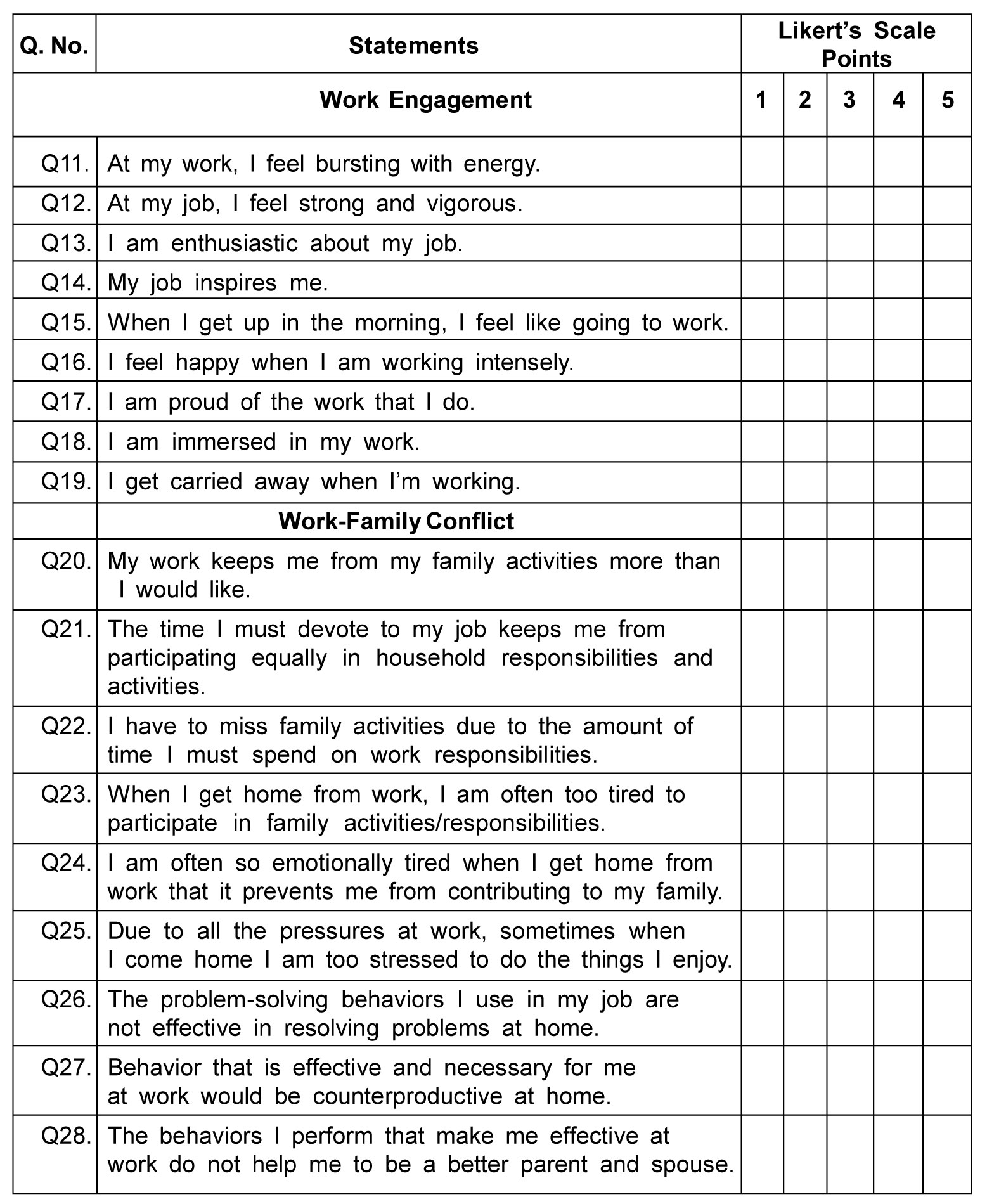

The survey has used the five-point Likert's scale (from 1 = Strongly Disagree to

5 = Strongly Agree) to determine the measures of the study (FSOP, WFC, and work engagement) with closed statements.

FSOP was assessed by means of the 9 items developed by Jahn et al. (2003). Sample items for the scale of FSOP are "My organization has many programs and policies designed to help employees balance work and family life" and "My organization makes an active effort to help employees when there is a conflict between work and family life." The alpha coefficient for the present sample was 0.84 for FSOP. Work engagement was measured by the scale developed by Schaufeli et al. (2006) which consists of 9 items. Sample items include "At my work, I feel bursting with energy" and "My job inspires me." The coefficient alpha value for this scale with the present sample was 0.82. WFC was assessed by the 9-item scale developed by Carlson et al. (2000). Sample items of the scale are "I have to miss family activities due to the amount of time I must spend on work responsibilities" and "Due to all the pressures at work, sometimes when I come home I am too stressed to do the things I enjoy." The alpha coefficient for the present sample was 0.87 for WFC. One item was constructed to measure self-reported absenteeism in terms of the number of days absent in the last working month. The answers are coded as No absence (0),

1-2 days (1), 3-4 days (2), 5-6 days (3), 6-7 days (4), more than 7 days (5).

In addition to these quantitative measures, qualitative data in the form of machine operator's own reasons for their unscheduled absenteeism were collected. Respondents were asked to explain all possible reasons for their unscheduled absenteeism and all the answers from the 50 machine operators were then analyzed for certain trends or patterns across cases.

Data Analysis

Descriptive analysis was used to measure the level of FSOP, WFC, work engagement, and absenteeism, and correlation analysis was used to determine the direction and strength of the relationship among the variables. Further, the correlation coefficients can reveal the significant relationship between the study variables at 5% level (p 0.05) to examine the hypothesized relationships. The impact of independent variables on dependent variable was assessed by using linear regression analysis, which additionally illustrated the mediation role of work engagement between the relationship of the study variables. SPSS version 25 was utilized to analyze the quantitative data and for the regression and mediation, "Andrew's Process Macro for SPSS" version 3.5 was applied. Moreover, a simple content analysis was used to summarize the reasons for unscheduled absenteeism of the machine operators in the particular selected apparel firm.

Results

Quantitative Analysis

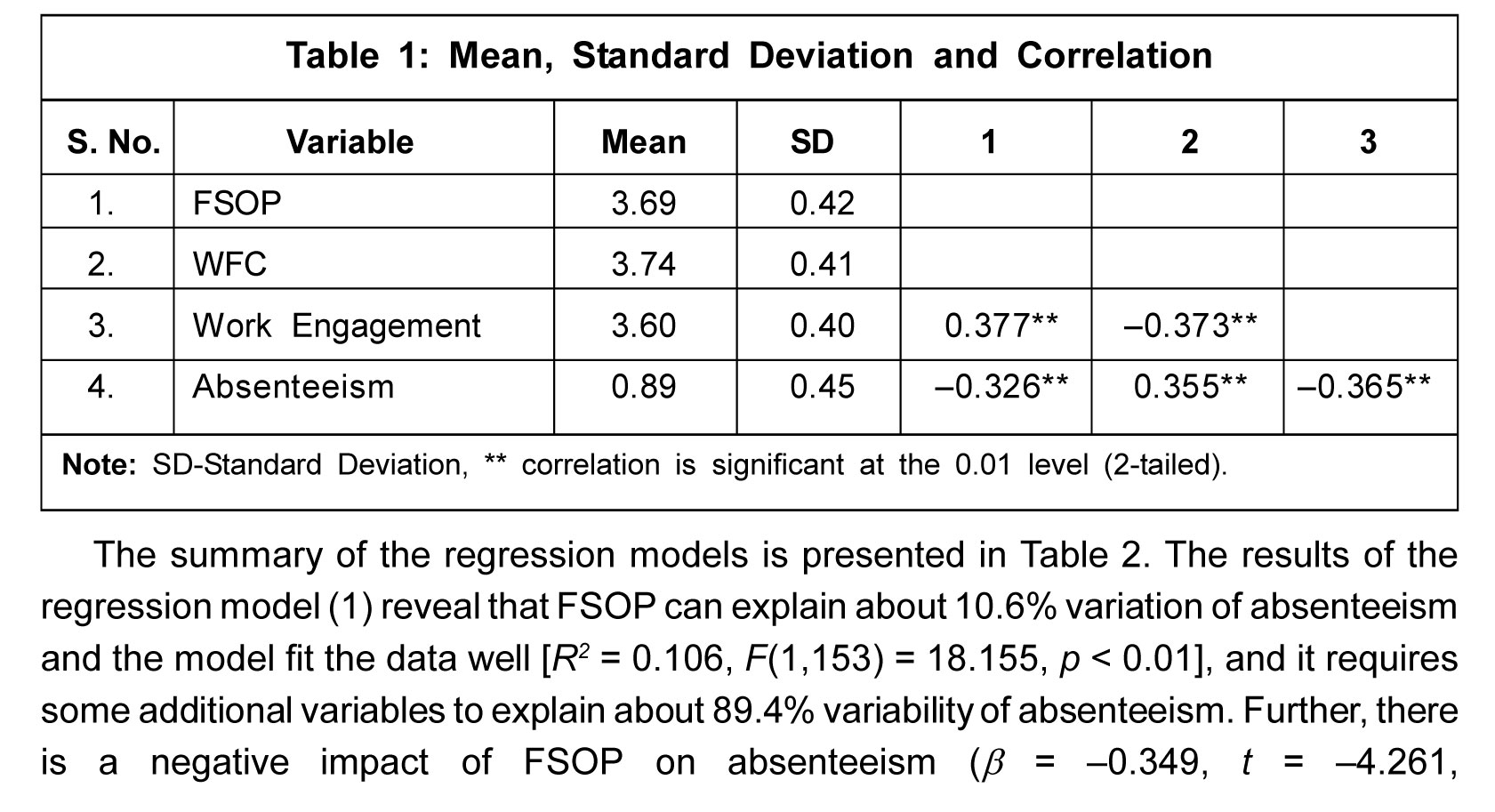

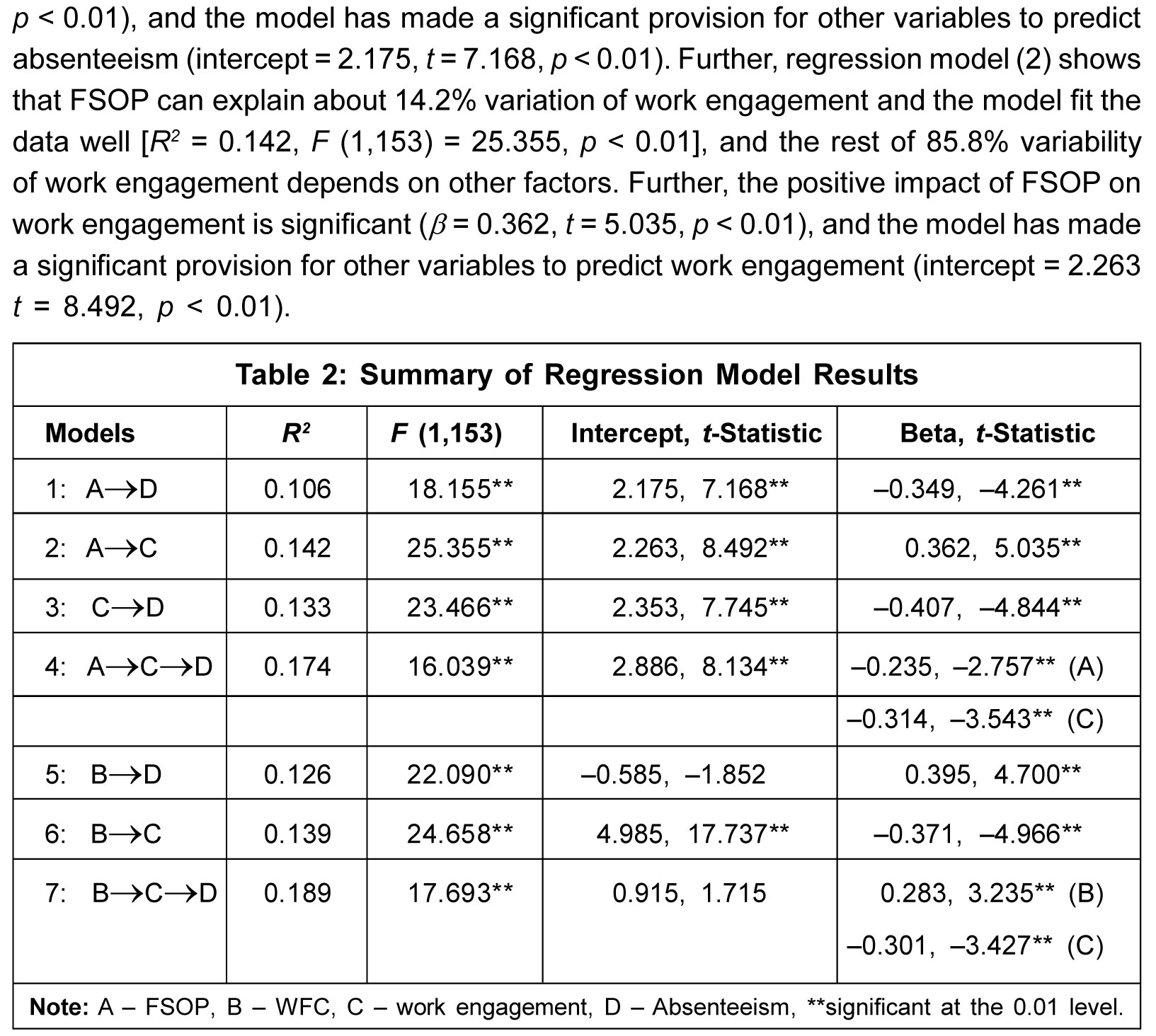

The means, standard deviations, and correlations among the study variables are presented in Table 1. Statistical estimations of overall responses show that the mean values of the variables FSOP, WFC, work engagement have high-level attributes and the variable absenteeism has low-level attributes as per the decision criteria. The respective standard deviation also shows the lowest spread of the variable measures. Correlation estimates indicate that the study variables have statistically significant linear correlation coefficients at 1% significant level (p 0.01). There is a moderate negative relationship that exists between FSOP and absenteeism, work engagement and absenteeism, WFC and work engagement, respectively -0.326, -0.365, and -0.373, even at 1% level, and there is moderately positive relationship that exists between WFC and absenteeism, FSOP and work engagement, respectively 0.355 and 0.377, even at 1% level. Hence, all the correlations were significant and in the expected direction; the results of correlation analysis confirm the acceptance of H1, H2, H3, H4, and H5 significantly.

The results of the regression model (3) uncover that work engagement can explain about 13.3% variation of absenteeism and the model fit the data well [R2 = 0.133, F (1,153) = 23.466, p < 0.01], and it requires some additional variables to explain 86.7% variability of absenteeism. Further, there is a negative significant impact of work engagement on absenteeism (b = -0.407, t = -4.844, p < 0.01), and the model has made a significant provision for other variables to anticipate absenteeism (intercept = 2.353, t = 7.745,

p < 0.01). Moreover, regression model (4) reveals that FSOP, work engagement can explain about 17.4% variation of absenteeism and the model fit the data well [R2 = 0.174, F (1,153) = 16.039, p < 0.01], and the rest of work engagement's variability depends on external factors. Further, the negative impact of FSOP, work engagement on absenteeism are significant (b = -0.235, -0.314, t = -2.757, -3.543, p < 0.01), and the model has made a significant provision for other variables to anticipate absenteeism (intercept = 2.886, t = 8.134, p < 0.01).

The results of the regression model (5) reveal that WFC can explain about 12.6% variation of absenteeism and the model fit the data well [R2 = 0.126, F (1,153) = 22.090, p < 0.01], and it requires some external factors to explain about 87.4% variability of absenteeism. Further, there is a positive significant impact of WFC on absenteeism (b = 0.395, t = 4.700, p < 0.01). Regression model (6) uncovers that WFC can explain about 13.9% variation of work engagement and the model fit the data well [R2 = 0.139, F (1,153) = 24.658, p < 0.01], and the rest of the variability of work engagement depends on external factors. Further, the negative impact of WFC on work engagement is significant (b = -0.371, t = -4.966, p < 0.01), and the model has made a significant provision for external variables to anticipate work engagement (intercept = 4.985, t = 17.737, p < 0.01). Finally, regression model (7) reveals that WFC, work engagement can explain about 18.9% variation of absenteeism and the model fit the data well [R2 = 0.189, F (1,153) = 17.693, p < 0.01], and the rest of the 81.1% work engagement's variability depends on external factors. Further, the positive impact of WFC and negative impact of engagement on absenteeism are significant (b = 0.283, -0.301, t = 3.235, -3.427, p < 0.01), and the model has made an insignificant provision for other variables to predict absenteeism (intercept = 0.915, t = 1.715, p > 0.05).

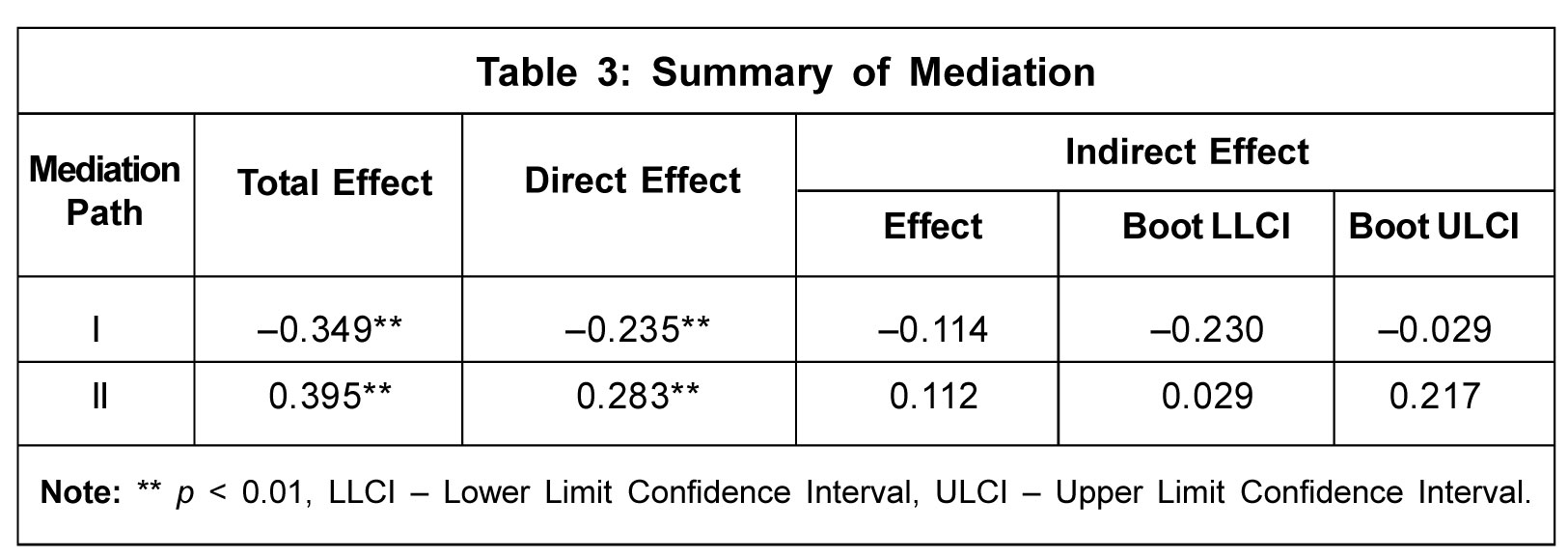

Table 3 reveals the summary of mediation analysis and in the path (I) the total effect (FSOP on absenteeism) is -0.349 with p < 0.01. The effect of FSOP remains significant after work engagement controlled the relationship (direct effect), but the strength of the relationship has reduced from -0.349 to -0.235. There is an indirect effect of FSOP on absenteeism through work engagement with the effect size of -0.114. The proportion of the mediation effect is 32.66% (indirect effect/total effect * 100). The mediation effect is significant as per the LLCI and ULCI (the value of zero has not been in the range of confidence limits). Further, in path (II) the total effect (WFC on absenteeism) is 0.395 with p < 0.01. The effect of WFC remains significant after work engagement controlled the relationship, but the strength of the relationship has reduced to 0.283. There is an indirect effect of WFC on absenteeism through work engagement with an effect size of 0.112. The proportion of the mediation effect is 28.35%. The mediation effect is significant as per the LLCI and ULCI. Hence, these results confirm the acceptance of H6 and H7 significantly.

Qualitative Analysis

The qualitative responses were provided by the women machine operators. Their possible reasons were stated as the answers for unscheduled absenteeism. The participants who are married and who are above 26 years of age have a common answer which is family responsibilities as shown by these examples:

- "I have children and I need to take care of them when they are sick, and sometimes I have to take them to the hospital for further treatment". (Nilanthy, 32 years)

- "I have to deal with my children's nursery/school matters such as meetings and functions". (Thenmoli, 34 years)

- "I have to look after my aged mother and need to take her to the clinic". (Vimalathevy, 32 years)

Another category of the respondents who are above 21 years of age have a problem with the morning shift timing. Most of the young respondents are of the opinion that in the early morning they feel drained of energy, bored, and frustrated to wake up in the early morning as per these examples,

- "Morning shift is the main reason for my absence, because I feel lazy to wake up in the early morning". (Kukapriya, 23 years)

- "I feel bored to go to work especially in the morning shift". (Madhusika, 22 years)

- "Sometimes I cannot wake up on time, therefore, I have to miss my bus". (Thenuja, 24 years)

Health issues and sickness are the general reasons for the absenteeism among all participants, for instance,

- "I have migraine headache problem, therefore, I cannot attend work due to the pain". (Meenaloginy, 36 years)

- "Sometimes I feel pain in my body (neck pain and leg pain) after a long period of work". (Angella, 24 years)

- "Fever and cold are the general reasons for my absenteeism". (Kijany, 25 years)

There were different answers about workplace-related reasons for unscheduled absenteeism among the respondents such as:

- "Pressures from the production supervisors are the reason for my unscheduled absence". (Nithujini, 22 years)

- "Work pressures, aggressive words and behaviors of our supervisors/managers are sometimes forcing me to take leaves". (Jeyanthi, 23 years)

Society and culture also play an important role in unscheduled absenteeism as per these examples:

- "I normally take leave when there is kovil (temple) function, wedding function, funeral, and birthday celebration". (Kenuka, 24 years)

- "I'm a member of some society-related associations and groups. Therefore, when there is any meeting I have to attend". (Rathivathany, 29 years)

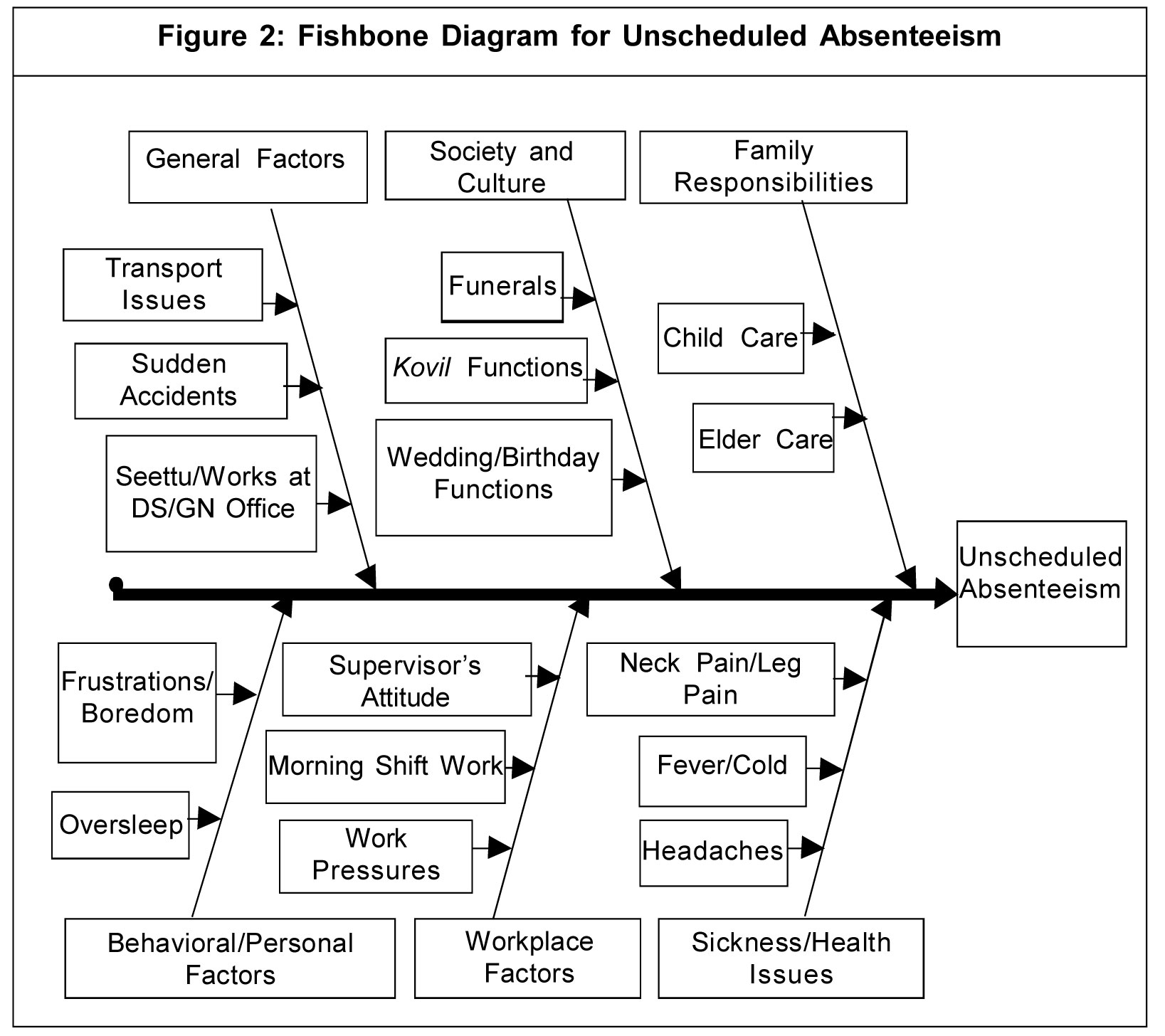

Some other personal reasons for the unscheduled absenteeism which were stated by the respondents are Seettu (informal money-saving mechanism), personal responsibilities at divisional secretariat/Grama Niladhari office, exams, accidents, and transport problems. All the reasons for unscheduled absenteeism have been shown in a fishbone diagram (Figure 2).

Discussion

To address the objectives of the study, the study findings have featured that family responsibilities which include childcare, eldercare responsibilities, and sickness such as headaches, neck pain and leg pain, fever, cold, and society and cultural factors such as funerals, wedding and birthday functions, kovil celebrations, and workplace-related factors which include work pressure due to work/management/supervisors, work-related attitudes and behaviors of the supervisors, morning shift time and some general factors are the causes for unscheduled absenteeism of machine operators. Those reasons cannot be forecast in advance. Even though wedding/birthday functions are predictable, for other reasons, informing leave in advance is not possible. Therefore, the management has to live with the unscheduled absenteeism, even if it is a disturbing problem for manufacturing operations.

High level of FSOP and work engagement among the workers clearly show the support of the firm in relation to worker's families and how much those workers are involved in their tasks with dedication. The production-oriented business firms are heavily dependent on the input of manpower, therefore, even if one production worker (input) is absent, then it is a loss for the firm as per the level of absenteeism. Further, the study confirms statistically significant relationship between the variables. It has been found that FSOP plays a significant negative role towards absenteeism as indicated by Cook (2009) and Haar and Roche (2010), and a significant positive role towards work engagement as per Matthews et al. (2014) and Hammer et al. (2015). Soane et al. (2013) and Ahuja and Modi (2015) endorsed the significant negative relationship between work engagement and absenteeism, and additionally, this study strongly reasserts their endorsement. Moreover, a significant positive relationship between WFC and absenteeism is in line with recent studies (Ugoani, 2015; and Shekhar, 2016). The significant negative relationship between WFC and work engagement is also in line with recent studies (Mohd et al., 2016; and Shekhar, 2016).

According to the Social exchange theory, when management practices family-supportive policies and efforts, then the workers will pay the organization back by regularly attending work to perform their scheduled duties. Further, physical and mental involvement towards the duties is another way of payback. Likewise, when the employees are more engaged, they become more motivated and energetic, which can force them to attend regularly. WFC can have a contribution to increasing the burden of absenteeism. As per the Job demands-resources model theory, WFC is a job demand that leads to burnout, and ultimately promotes health issues and depression which are the root cause of absenteeism. Further, WFC can drain the energy, motivation, and happiness of the workers which are crucial for work engagement. Finally, this study has confirmed the mediating effect of work engagement between FSOP and absenteeism in line with Kossek et al. (2011), and between WFC and absenteeism in line with Bhalerao (2013).

Conclusion

The study was carried out to find the reasons for unscheduled absenteeism and to fill the knowledge gap in the Sri Lankan apparel sector by studying the relationships, impacts, and mediation roles. FSOP, WFC, and work engagement are showing the high-level attribute, and absenteeism is showing the low-level attribute according to the univariate analysis. The variables are significantly correlated with each other as per the correlation analysis. Moreover, the regression analysis confirmed the significant impact of variables on each other along with the significant mediation role of work engagement. Further, family responsibilities, health issues, society and cultural factors, workplace-related factors, general factors, and personal/behavioral factors are the root causes for unscheduled absenteeism of machine operators.

This study contributes directly/indirectly to the selected apparel firm and also the entire apparel sector industries and production firms which heavily depend on a huge level of manpower by providing a clear picture about workers' mindset regarding family support, role conflicts, work engagement and absenteeism, and their interconnections and impacts. These findings may help practitioners to better understand the behaviors and issues related to the workforce. Moreover, it contributes to filling the research gap in the Sri Lankan apparel industry. The hypothetical relationship depicted in the proposed model is supported, and therefore the study additionally provided a theoretical contribution to the relevant theories such as Spillover theory, Social exchange theory, Job demands-resources model, and Steers and Rhodes process model theory along with Pull-push theory. Finally, the acceptably high alpha coefficients for the scales provide support for the reliability of the measures.

Apparel sectors are the ones that are heavily affected by the pandemic situation across the world. During the crisis, the apparel sectors faced many struggles for the smooth functioning of production and exports due to social distancing, quarantines, government's regulations and societal pressures. Generally, the apparel sectors are labor-intensive and because of the pandemic-related reasons, the issues of absenteeism and WFC increased during this situation. Work engagement among the employees also dramatically reduced because of the virus spreading, fear of the situation, and pressures from society and home. This situation has provided the opportunity to show support towards workers and worker's families; especially during the lockdowns, the company can support financially, or they can help to meet the basic needs, which can ultimately enhance FSOP among the workers. Therefore, this study can be of significance during pandemic situation to understand how to manage the workers, how much the factors are correlated with each other, and how to think rationally even in such situations.

When the supervisors/managers are supportive, it can have a positive impact and encourage the workers to have a conversation with the supervisors/managers about the conflict they are experiencing and can make a dramatic change in WFC. Conducting training/workshops on balancing the work and family roles can make the workers more aware of the issues and help them to balance work and family. Adapting the work-life balance policies/procedures such as surveys, disseminating information on work-life balance policies to employees, and including the work-balance issues in the induction/orientation program can make a difference. There are different tool kits that can be used by employers to address work-life balance that help to develop and sustain the work-life balance of their workers. Further, management can have a feedback system that allows workers to anonymously express their opinions, issues and feelings. Providing stretching exercises between breaks can influence the physical condition of the workers after a long hour of machine operating work. Further, facilitating friendly competitions between production lines/segments and involving employees in social activities can help to make employees more engaged and excited.

Business sectors with a labor-intensive nature as a whole can implement many effective strategies to manage labor-related issues. Organizations that balance work and life can attract and retain workers, improve work execution, and lift worker's morale. Work-family struggle can be reduced by setting up family-accommodating schemes in the work environment like the provision for maternity, paternity, debilitating leaves, and medical insurance. Organizations may provide child care alternatives either on-location kid care, references to close to office kid care, or enhancing the salaries for the families putting their kids in a child care center. There is an urgency for government policy to protect employees who are expecting an improvement in their working conditions and environment. In countries like Turkey, where job relationship is not controlled and the role of labor associations or unions is inconsequential, workers rely upon their managers for help in adjusting their work and family lives. Tragically, as most managements are the reason for those imbalances, the workers end up in a troublesome situation. Therefore, it is important to implement government policies to improve the working conditions of the employees, which can ultimately resolve many issues.

Limitations and Future Scope: The study has been carried out at a selected apparel firm and focused on a limited number of variables/sample size; sampling method used resulted in a fairly low response rate in comparison with the sample size, and presented with a middle option as 'neutral' on the Likert scale, which leads the respondents to select that option when they did not have a clear idea. Despite these limitations, researchers can utilize these findings to further investigate FSOP, WFC, work engagement, and absenteeism by involving a large number of respondents, including more apparel sector firms, involving other employees in the apparel sector who are not directly linked with production line. Moreover, studies can use in-depth interviews and a longitudinal approach to the variables to find out the reasons for unscheduled absenteeism for more comprehensive results. There is a widespread belief that absenteeism is harmful to the organization. However, absenteeism to some extent may be really 'healthy' for organizations because it can allow for the temporary escape from stressful situations, thereby contributing to the mental health of workers. Therefore, it would be interesting for future researchers to investigate the extent of absenteeism that does or does not have negative consequences for the organization.

References

- Abdur R R and Atm A (2015), "Challenges of Ready-Made Garments Sector in Bangladesh", BUFT Journal, Vol. 1, No. 3, pp. 77-90.

- Ahuja S and Modi S (2015), "Employee Work Engagement: A Multi-Dimensional State of the Art Review", International Journal of Marketing and Technology, Vol. 5, No. 3, pp. 51-69.

- Allen T D (2001), "Family-Supportive work Environments: The Role of Organizational Perceptions", Journal of Vocational Behavior, Vol. 58, No. 3, pp. 414-435.

- Arokiasamy A R A and Tat H H (2019), "Organizational Culture, Job Satisfaction and Leadership Style Influence on Organizational Commitment of Employees in Private Higher Education Institutions in Malaysia", Amazon Investigation, Vol. 8, No. 19, pp. 191-206.

- Attridge M (2009), "Measuring and Managing Employee Work Engagement: A Review of the Research and Business Literature", Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health, Vol. 24, No. 4, pp. 383-398.

- Bakker A B (2017), "Job Crafting Among Health Care Professionals: The Role of Work Engagement", Journal of Nursing Management, Vol. 26, No. 3, pp. 321-331.

- Bedarkar M and Pandita D (2014), "A Study on the Drivers of Employee Engagement Impacting Employee Performance", Procedia - Social and Behavioural Sciences, Vol. 133, No. 1, pp. 106-115.

- Bellavia G M and Frone M R (2005), Work-Family Conflict: Handbook of Work Stress, Thousand Oaks, Sage Publications, California.

- Bethge M and Borngraber Y (2015), "Work-Family Conflicts and Self-Reported Work Ability Cross-Sectional Findings in Women with Chronic Musculoskeletal Disorders", BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, Vol. 16, No. 1, pp. 1-28.

- Bhalerao S K (2013), "Work Life Balance: The Key Driver of Employee Engagement", ASM's International E-Journal of Ongoing Research in Management and IT, Vol. 16, No. 1, pp. 1-9.

- Bragger J D, Rodrigguez O, Kutcher E J et al. (2005), "Work-Family Conflict, Work-Family Culture and Organizational Citizenship Behavior Among Teachers", Journal of Business and Psychology, Vol. 20, No. 2, pp. 303-324.

- Brummelhuis L L, Bakker A B and Euwema M C (2010), "Is Family-to-Work Interference Related to Co-Workers 'Work Outcomes?", Journal of Vocational Behavior, Vol. 77, No. 3, pp. 461-469.

- Carlivati P (2007), "A Balancing Act", ABA Bankers News.

- Carlson D, Kacmar K M and Williams L J (2000), "Construction and Initial Validation of a Multidimensional Measure of Work-Family Conflict", Journal of Vocational Behavior, Vol. 56, No. 2, pp. 249-276.

- Cikes V, Maskarin R H and Crinjar K (2018), "The Determinants and Outcomes of Absence Behavior: A Systematic Literature Review", Social Sciences, Vol. 7, No. 8, pp. 120-156.

- Cook A (2009), "Connecting Work-Family Policies to Supportive Work Environments", Group & Organization Management, Vol. 34, No. 2, pp. 206-240.

- Cropanzano R and Mitchell M S (2005), "Social Exchange Theory: An Interdisciplinary Review", Journal of Management, Vol. 31, No. 6, pp. 874-900.

- Demerouti E, Bakker A B, Nachreiner F and Schaufeli W B (2001), "The Job Demands Resources Model of Burnout", Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 86, No. 3, pp. 499-512.

- Dheerasinghe R (2017), "Garment Industry in Sri Lanka Challenges, Prospects and Strategies", Staff Studies, Vol. 33, No. 1, pp. 33-72.

- Edwards P and Greasley K (2010), Absence from Work, Report of the European Working Conditions, Eurofound Publications.

- Eisenberger R, Lynch P, Aselage J and Rohdieck S (2004), "Who Takes the Most Revenge? Individual Differences in Negative Reciprocity Norm Endorsement", Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, Vol. 30, No. 6, pp. 787-799.

- Galinsky E, Aumann K and Bond J T (2008a), "The 2008 National Study of the Changing Workforce", New York Families and Work Institute.

- Galinsky E, Bond J T and Sakai K (2008b), 2008 National Study of Employers, Families and Work Institute, New York.

- Gallup (2013), "The State of the Global Workplace: Employee Engagement Insights for Business Leaders Worldwide", Gallup Inc, Washington.

- Ghislieri C and Colombo L (2014), "Work-Family Conciliation: Theoretical Approaches and Constructs", Psychology of Work-Family Conciliation, Vol. 15, No. 1, pp. 3-30.

- Golden L (2011), Flexible Work Schedules: What are we Trading Off to Get them? Monthly Labor Review, Vol. 124, No. 3, pp. 50-67.

- Gouldner A (1960), "The Norm of Reciprocity: A Preliminary Statement", American Sociological Review, Vol. 25, No. 2, pp. 161-178.

- Haar J and Roche M (2010), "Family Supportive Organization Perceptions and Employee Outcomes: The Mediating Effects of Life Satisfaction", The International Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 21, No. 6, pp. 999-1014.

- Hammer L B, Johnson R C, Crain T L et al. (2015), "Intervention Effects on Safety Compliance and Citizenship Behaviors: Evidence from the Work, Family and Health Study", Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 101, No. 2, pp. 190-208.

- Hammer L B, Kossek E E, Bodner T and Crain T (2013), "Measurement development and validation of the family supportive behavior", Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, Vol. 18, No. 3, pp. 285-296.

- Hassan Z, Dollard M F and Winefield A H (2010), "Work-Family Conflict in East vs. Western Countries", Cross Cultural Management, Vol. 17, No. 1, pp. 30-49.

- Jahn E W, Thompson C A and Kopelman R E (2003), "Rational and Construct Validity Evidence for a Measure of Perceived Organizational Family Support (POFS)", Community, Work and Family, Vol. 6, No. 2, pp. 123-140.

- Kahn W A (1990), "Psychological Conditions of Personal Engagement & Disengagement at Work", Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 43, No. 6, pp. 692-724.

- Kelegama S and Epaarachchi R (2003), "Productivity, Competitiveness and Job Quality in Garment Industry in Sri Lanka", Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka.

- Kinnear K, Juhl H J, Eskildsen J et al. (2006), "Determinants of Absenteeism in a Large Danish Bank", International Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 17, No. 9, pp. 1645-1658.

- Kocakulah M C (2016), "Absenteeism Problems and Costs, Causes and Effects", International Business & Economics Research Journal, Vol. 15, No. 3, pp. 89-96.

- Kossek E E (2005), "Workplace Policies and Practices to Support Work and Families", Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, NJ.

- Kossek E E, Baltes B B and Matthews R A (2011), "How Work-Family Research Can Finally Have an Impact in Organizations", Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Vol. 4, No. 2, pp. 352-369.

- Kottawatta K (2013), "Impact of Attitudinal Factors on Job Performance of Executives and Non-Executive Employees in the Apparel Industry in Sri Lanka", Sri Lankan Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 16-33.

- Kumara J and Fasana S F (2018), "Work Life Conflict and its Impact on Turnover Intention of Employees: The Mediation role of Job Satisfaction", International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, Vol. 8, No. 4, pp. 478-484.

- Martin A (2017), "Absenteeism as a Reaction to Harmful Behavior in the Workplace", German Journal of Industrial Relations, Vol. 28, No. 2, pp. 227-254.

- Matthews R A, Mills M J, Trout R C and English L (2014), "Family-Supportive Supervisor Behaviors, Work Engagement and Subjective Well-Being: A Contextually Dependent Mediated Process", Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, Vol. 19, No. 2, pp. 168-181.

- Mohd I H, Shah M M and Zailan N S (2016), "How Work Environment Affects the Employee Engagement in a Telecommunication Company", International Conference on Business and Economics, Vol. 6, No. 1, pp. 1-9.

- Musgrove C, Ellinger A E and Elainer A D (2014), "Examining the Influence of Strategic Profit Emphases on Employee Engagement and Service Climate", Journal of Workplace Learning, Vol. 26, No. 3, pp. 152-171.

- Myilswamy and Gayatri R (2014), "A Study on Employee Engagement: Role of Employee Engagement in Organizational Effectiveness", International Journal of Innovative Science, Engineering & Technology, Vol. 23, No. 2, pp. 56-89.

- Natsuda K, Goto K and Thoburn J (2010), "Challenges to the Cambodian Garment Industry in the Global Garment Value Chain", The European Journal of Development Research, Vol. 22, No. 4, pp. 469-493.

- Osario B D, Aguado M L and Villar C (2015), "The Impact of Family and Work-Life Balance Policies on the Performance of Spanish Listed Companies", Journal of Management, Vol. 17, No. 4, pp. 214-236.

- Raja H (2019), "The Impact of Employee Absenteeism on Organizational Productivity, Case of Service Sector", International Journal of Research in Humanitarian, Art and Literature, Vol. 7, No. 4, pp. 581-594.

- Ranaweera H (2014), "Uplifting Sri Lankan Apparel Industry Through Innovation Management to Face the Challenges in the Post MFA Era", University of Moratuwa, Sri Lanka, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 75-82.

- Robbins S P and Judge T A (2004), Organizational Behavior, Pearson Education, Incorporated, New Jersey.

- Russo M, Shteigman A and Carmeli A (2015), "Workplace and Family Support and Work-Life-Balance: Implications for Individual Psychological Availability and Energy at Work", The Journal of Positive Psychology, Vol. 11, No. 2, pp. 173-88.

- Saeed R, Hameed R, Tufail S et al. (2013), "The Impact of HRM Practices on Employee Commitment and Turnover Intention: A Case of Service Sector in Pakistan", Journal Basic Applied Scientific Research, Vol. 3, No. 10, pp. 152-157.

- Schaufeli W B (2013), What is Engagement? Employee Engagement in Theory and Practice, Routledge, London.

- Schaufeli W B, Bakker A B and Salanova M (2006), "The Measurement of Work Engagement with a Short Questionnaire: A Cross-National Study", Educational and Psychological Measurement, Vol. 66, No. 4, pp. 701-716.

- Schaufeli W B, Bakker A B and Rhenen V W (2009), "How Changes in Job Demands and Resources Predict Burnout, Work Engagement and Sickness Absenteeism", Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 30, No. 7, pp. 893-917.

- Schaufeli W B and Bakker A B (2004), "Job Demands, Job Resources and their Relationship with Burnout and Engagement: A Multi-Sample Study", Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 25, No. 3, pp. 293-315.

- Shankar T and Bhatnagar J (2010), "Work Life Balance, Employee Engagement, Emotional Consonance/Dissonance & Turnover Intention", Indian Journal of Industrial Relations, Vol. 46, No. 1, pp. 74-87.

- Shaw J (2010), "From Kuwait to Korea: The Diversification of Sri Lankan labor Migration", Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, Vol. 15, No. 1, pp. 59-70.

- Shekhar T (2016), "Work Life Balance and Employee Engagement-Concepts Revisited", International Journal of Education and Psychological Research, Vol. 5, No. 1, pp. 32-34.

- Soane E, Shantz A, Alfes A et al. (2013), "The Association of Meaningfulness, Wellbeing and Engagement with Absenteeism: A Moderated Mediation Model", Human Resource Management, Vol. 52, No. 3, pp. 441-456.

- Thatshayini P and Rajini P A D (2018), "Occupational Safety and Health Hazards of the Apparel Sector: Perspective of Northern Province Employees of Sri Lanka", Journal of Business Studies, Vol. 5, No. 1, pp. 26-47.

- Ugoani J N (2015), "Work-Family Role Conflict and Absenteeism among the Dyad", Advances in Applied Psychology, Vol. 1, No. 2, pp. 145-154.

- Ullah N M A S and Rahuman H (2013), "Compliance Management Practices on Readymade Garment Industry in Bangladesh: An Exclusive Study", In 9th Asian Business Research Conference, pp. 1-9.

- Wang P and Walumbwa F O (2007), "Family-Friendly Programs, Organizational Commitment, and Work Withdrawal: The Moderating Role of Transformational Leadership", Personnel Psychology, Vol. 60, No. 2, pp. 397-427.

- Westman M (2002), Crossover of Stress and Strain in the Family and in the Workplace, Vol. 2, No. 4, pp. 143-181, JAI Press/Elsevier Science.

- Zedeck S and Mosier K L (1990), "Work in the Family and Employing Organization", American Psychologist, Vol. 45, No. 2, pp. 240-251.