July '21

The IUP Journal of Organizational Behavior

Archives

Training Needs of Self-Help Groups (SHGs)

Siddhartha Thyagarajan

(Formely) Assistant Professor, Department of Management, Faculty of Business and Economics, Debre Tabor University, Debre Tabor, Ethiopia. E-mail: si2000si2000@yahoo.com

T Nambirajan

Professor and Supervisor, Department of Management Studies, Pondicherry University, Puducherry 605014, India. E-mail: rtnambirajan@gmail.com

Ganeshkumar Chandirasekaran

Assistant Professor, Indian Institute of Plantation Management, Bangalore 560056, India; and is the corresponding author. E-mail: gcganeshkumar@gmail.com

The objective of the paper is to study the training needs of Self-Help Groups (SHGs) in the Union Territory of Puducherry. The study variables were developed from the existing review of literature relating to SHGs' training needs and 251 samples of primary data of SHGs were gathered using a well-structured questionnaire. The statistical package of SPSS was utilized to analyze the data using the techniques of descriptive statistics with frequency analysis and simple mean analysis, ANOVA, chi-square test and correspondence analysis. The results show that a majority of the groups (29.9%) have two persons who have undergone formal training in some activity, while a good proportion of groups (22.7%) have no members who have undergone any formal training.

Introduction

"A women's Self Help Group (SHG) is a small economically homogenous affinity group of rural poor women, voluntarily coming together to save a small amount of money regularly, to agree to contribute to a common cause, to meet emergent needs on a mutual help basis, to practice collective decision making, to solve conflicts through leadership and to provide collateral free loans with terms and conditions decided by the group (Thyagarajan et al., 2019)". The Tamil Nadu Corporation for Development of Women defines SHG thus: "An SHG is a small economically homogenous affinity group of rural poor, voluntarily formed to save and contribute to a common fund to be lent to its members as per group decision and for working together for social and economic uplift of their family and society". SHGs have certain characteristic features in their formation and functioning: ideal size of groups should be 10 to 20 members; one family one member in each group; the group can be only women, only men or mixed groups; members should be from similar socioeconomic background; savings is compulsory; regular meetings are compulsory; regular weekly, fortnightly or monthly attendance for meetings is compulsory; and the group elects group leaders such as the President, Secretary and Treasurer to organize activities and empowers them to operate bank accounts. The SHGs perform their functions in an organized manner or operations like election of office bearers, rotation of office bearers, periodical and regular meetings, decision through consensus regarding thrift and decision regarding internal lending (Rishikesh and Ganeshkumar, 2016).

During the operation of the SHG, the following records are maintained as per guidelines of the affiliating organizations: attendance register of members, minutes book of meetings, savings and loan register, member passbooks for banks and rules and regulations book. The operations of SHG is for thrift and credit, hence the financial aspect of the SHG is to obtain funds from as many sources as possible. Some of the sources of funding for an SHG are thrift and regular savings of members, membership fees, internal lending to members and interest earnings, outsider contributions by NGOs, fines and penalties for late payments and bank loans. The duty of SHG towards its members is to perform certain important functions within their groups, such as encouraging savings, providing internal lending, maintenance of records of transactions, conducting member-oriented programs, creating linkages to financial institutions and undertaking trainings for capacity building of its members. The SHG movement has provided important benefits to the members, such as social empowerment, economic independence, self-determination, skill and knowledge enhancement, improved literacy, improved credit worthiness, learning culture of thrift, health and environmental awareness and understanding of formal work environment which can serve to improve their ability in social orientation and economic development (Ganesh et al., 2017).

The activities of SHG in India initially had been in areas of creation of social awareness, education, counseling and disease eradication. Now, they also involve in activities of economic development in the form of trading, farming and manufacturing through the formation and management of microenterprises producing products and performing activities in areas such as agro-based industries, retailing, animal husbandry, dairy, tailoring, garment selling, carpentry, welding, fruit processing, bakery, beauty salons, brick making, pottery and artisan work, carpentry, etc. Some of the other income generating activities of the SHG have been in the areas of agriculture, agro-based-seed production, beekeeping, nursery management, small retail store, brick making, livestock development in the form of goats, cows and poultry, bicycle repair and maintenance, milk procurement and processing, leaf plate making, carpentry, iron smithing, garment shops in the form of tailoring, embroidery and knitting, beauty salon, fruit, vegetable selling and processing, motor winding and such other areas which have economic potential (Siddhartha et al., 2017a).

SHGs have been able to provide an important benefit in the form of empowerment of its members through group participation. Empowerment can be described as the process by which individuals or groups gain power and ability to take control of their lives by means of access to resources, increased participation in decision-making, and increased control over benefits leading to increased self-confidence, self-esteem, self-respect and wellbeing. In other words, empowerment leads to self-power, self-reliance, self-choice, life of dignity in accordance with one's values, capable of fighting for one's rights, independence, own decision making, being free, awakening which in turn leads to individual capacity building (Siddhartha et al., 2017b).

Empowerment of the members can be categorized into many forms:

Economic Empowerment: This means the ability to earn and decide to spend money. The main areas of employment for rural persons have been in the farms performing agricultural operations. This being seasonal in nature and inconsistent in availability, the women have been led to borrowings and debt conditions leading to economic liability. The SHG participation has been able to provide a means of savings for economic liberation and independence from such situations.

Social Empowerment: Social empowerment indicates that the members should have a rightful place in society and have the right and ability to use resources.

Political Empowerment: Political empowerment indicates that the person should be capable of analyzing, organizing and mobilizing the surroundings for transformation (Jamshi and Ganeshkumar, 2017).

The SHG participation has provided enormous benefits and impact to its members. While certain benefits have been direct, others have been indirect benefits. Some of these benefits, both direct and indirect, are increase in savings of group members, access to internal credit, access to external credit, increased source of income, access to savings account, employment generation for members, improved credit mobilization facility, increased skill development, increased success in microenterprise operations, increased awareness on member's nutrition, communicable diseases, sanitation and environment, improved decision-making, participation in village administration, participation in community programs, improved communications and learning, improvement in leadership qualities, increased social status and recognition of family members, increased social empowerment, increased nutrition, interaction and access to Non-Governmental Organizations and interaction with other formal institutions and access to improved daily necessities like clean water, sanitation, medical facilities (Thyagarajan et al., 2018).

Though the SHG have been able to perform their functions successfully in the improvement of their wellbeing, there have been obstacles and many problems which have been faced in its path. Some of these are lower participation by the really needy poor, low survival rate for microenterprises created by SHGs, poor income from income generating activities, non-participation by many persons in groups, non-utilization of allocated funds by the banks (Thyagarajan et al., 2018). Despite the efforts of the organizations in the formation of SHGs, there have been many instances where SHGs have not been successful in operations. Therefore, the sustainability of the operation of SHGs may need several basic requirements which can lead to the success of the SHG concept. Some of these prerequisites for SHG success are, firstly, the groups should be homogenous in nature with similar economic conditions. Secondly, the groups should have an ideal size of between 10 to 20 members for better coordination, cooperation and assistance. Thirdly, the groups should be voluntary in nature and have persons with many skills which would enable varied choice of activities. Fourthly, the groups should have interests and an agenda of participation in several community-based activities including microenterprises and the groups should have a consensus approach to decision-making and finally the groups should be apolitical in nature (Ganeshkumar et al., 2019). Multiple organizations have been involved in the nurturing, formation and promotion of SHGs, which have also been instrumental in guiding them into successful operations. Some of these organizations have been governmental agencies such as municipalities and corporations implementing government-sponsored schemes, social development corporations of state governments, NGOs, public sector banks, rural banks, cooperative banks, microfinance institutions and SHG federations. These organizations have contributed vastly to the development of SHG in much of the urban and rural areas of India (Thyagarajan et al., 2019) and this study will answer the research question on the training needs of SHG in Puducherry region (Siddhartha et al., 2019).

Literature Review

Poverty can be described as a pronounced deprivation of wellbeing of an individual which can also be stated as not being able to satisfy the basic needs because one possesses insufficient money to buy the needed materials and services. Poverty as a condition exceeds all social and political boundaries (Ganeshkumar et al., 2014). The Gujarat Institute of Development Studies has described poverty as "a situation of pronounced deprivation in wellbeing, in other words being hungry, lacking shelter, to be sick and not being cared for, to be illiterate which leads to earning below the margins of existence and which can be described in other words as where the survival need exceeds the income of the individual". Poverty can be viewed through a multiplicity of factors not just in terms of income and calorie intake but also access to credit, nutrition, healthcare, literacy, sanitation and other social infrastructural facilities needed (Arokiaraj et al., 2020a).

According to the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), poverty is related to income and people are said to be in poverty when they have been deprived of income to meet diet, material goods, amenities, standards and services. In India, the Planning Commission of India has provided a guideline to measure poverty, that is, per capita expenditure of less than 972 per month in rural areas and less than 1,407 in urban areas is treated as living below poverty line (Planning Commission Report of Expert Group for Review of Methodology for Measurement of Poverty, June 2014) which translates to approximately less than 33 per day in rural areas and less then 48 per day in urban areas as living below poverty line (Kumar and Nambirajan, 2013).

Poverty can be described using various terminologies, such as absolute poverty which refers to the state of severe deprivation of basic human needs which includes food, water, sanitation, clothing, shelter, healthcare, education and information. Chronic poverty refers to the time period of poverty that the person is affected by. Poverty that lasts a long time, that is, into many years, a lifetime or even more than one generation is referred to as chronic poverty, while transitory poverty refers to situations wherein persons move in and out of poverty for short periods of time due to disease, unemployment and social changes. Recurrent poverty pertains to being in and out of poverty many times over a time period. Poverty breadth refers to the different dimensions and the many ways in which people are affected by poverty, which can be in terms of lack of assets, lack of income, lack of nutrition, lack of health, lack of education or lack of status, lack of inclusion, marginalization and lack of access to common services such as financial and other services, etc. Poverty depth refers to how far below the poverty line the person exists. Positions far below the poverty line have been denoted as deep poverty, ultra poverty, absolute poverty or extreme poverty. Poverty in a country can also be evaluated by means of the exit-to-entry ratio of poverty which shows the percentage of persons who have exited poverty and the percentage of persons who have entered into poverty conditions within a given period of time. For example, an exit-to-entry ratio of 2.5:1 indicates that there is sufficient development for the state with exit being denoted greater than entry. Poverty always needs to be understood through its linkage to social vulnerability, social protection and development which provides an important means to identify the development activities for the poor (Paul et al., 2020).

Poverty is caused through the individual circumstances of the person. Some of the factors that can affect poverty are human capabilities, such as, education level, skill, experience, intelligence, health, handicap, age and work orientation. Social structure affects through culture, discrimination, race, sex, etc. The external factors which can induce poverty are agricultural cycles, natural disasters, droughts, floods, failure of crops, limited access to natural resources, agro climatic conditions of the region etc. The broad causes of poverty can also be classified in another way, namely, economic causes, governance causes, demographic and social causes and environmental causes. The economic causes mostly comprise unemployment, trade policy, tax policies, land distribution and ownership. The governance causes may be lack of democracy, poor law and order, poor management of resources, lack of infrastructure, large scale corruption and poor developmental opportunities. Social causes may be caste divisions, bondage, gender discrimination, social exclusion and domination of select groups. The demographic causes may be overpopulation, crime, post communism, war, discrimination, poor health conditions, diseases, individual and religious belief. Environmental factors may be fertility of land, availability of water, availability of minerals, other natural resources, seasonal drought, natural calamities, soil erosion, etc. (Paul et al., 2019).

Joy et al. (2008) studied the objective of factors determining group performance using socioeconomic factors and group's performance variables and research found that variables such as age, education, market perception, motivation, risk-orientation and innovativeness and training play a role in the performance of the group (Tsai, 2000). Ssewamala and Sherraden (2004) examined integrating savings into micro enterprises through community-based organizations promoting self-employment and found that integrating of savings, training and credit for microenterprises was found to be beneficial for the development of such enterprises and its owners (Tinker, 2003). Madlani (2009) explored the objective of concept, domain, rural marketing mix and limitations of women entrepreneurs using sample data collection through questionnaire and found that the problems of women entrepreneurs is lack of facilities for training, marketing, and transportation in rural areas (Kanitkar, 1994).

Swain and Wallentin (2009) studied the objective of empowerment of women using sample data collection through questionnaire for SHG bank linkage program from experimental and control groups and found that empowerment is lacking because of the excessive discriminatory systems. Empowerment comes through training, workshops and the inclusion in the decision-making process (Sooryamoorthy, 2007). Basargekar (2008) studied the objective with a view to finding the impact of microfinance through interview technique of 217 SHG members (De Mel et al., 2009). Swain and Wallentin (2009) explored whether SHG participation leads to asset creation via data collection on previously enlisted members and new members of SHGs and found that longer membership duration positively impacts asset creation. Training can lead to diversifying income streams and asset creation also in terms of livestock (Swain and Varghese, 2009). Midgley (2008) studied female empowerment through watershed management. A case study of SHGs in Orissa through a survey of SHG members in Ganjam district of Orissa found that microcredit has the potential to eradicate poverty and generate employment. SHG can be made more successful by training, education and creating awareness programs (Kumar, 2010).

Specific methods of poverty alleviation that the government has undertaken in the area of rural poverty mitigation are increasing knowledge and skill of farmers in the form of agricultural technology, conducting practical training in agriculture, conducting work demonstrations, providing medical and technical support for animal husbandry, widely developing irrigation agriculture and improving water harvesting schemes. Certain poverty alleviation schemes pertaining to health, hygiene and nutrition have been in areas of primary healthcare schemes, provision of safe drinking water, universalization of primary education, housing assistance to the shelter less, nutrition support, streamlining of public distribution and connectivity of the unconnected villages. Some of the other social protection measures for poverty abatement include unconditional cash transfers, conditional cash transfers, such as for a person for attending school, conditional cash transfers linked to social work, transfer of agricultural inputs such as fertilizers and seeds, asset transfer such as machinery and subsidized food transfer (Arokiaraj et al., 2020b).

Methodology

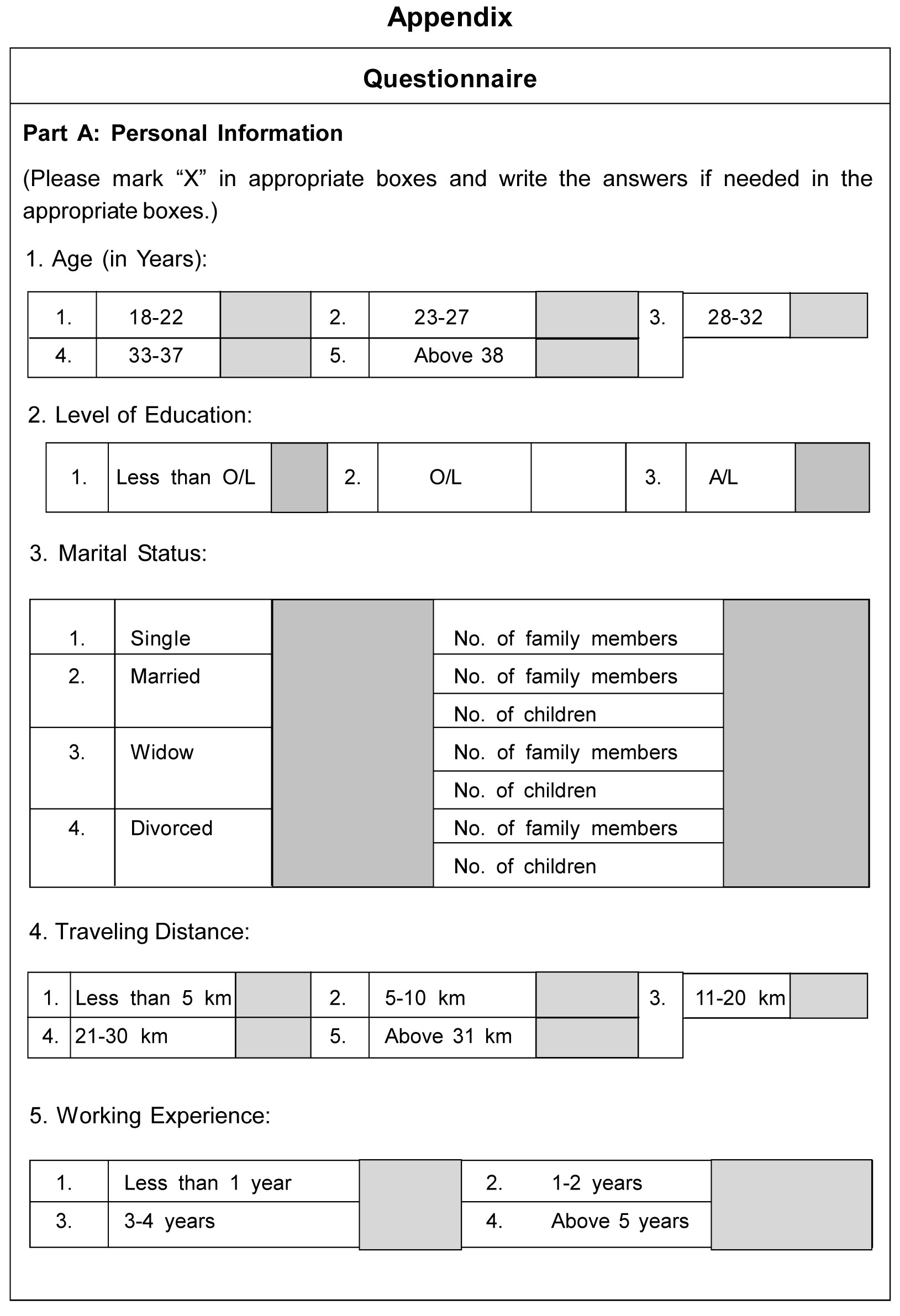

The purpose of the study is to analyze and describe the training needs of SHGs. It can therefore be understood that the study is descriptive in nature. First, subject experts' options survey was conducted on the identified variable for questionnaire (see Appendix) validity checking and required corrections were incorporated (Ganeshkumar and Nambirajan, 2013; and Ganeshkumar and Mohan 2014). The pilot survey of 30 SHGs was collected and initial Cronbach's alpha value was estimated for checking the reliability of the questionnaire. Primary data for the main study was collected through the survey method of 251 random samples of SHGs who were identified from the list of SHGs maintained in the various banks, NGOs and municipal bodies. The data was collected from the members and group leaders of SHGs by means of a well-structured questionnaire. The statistical package of SPSS was utilized to analyze the data using the statistical techniques of descriptive statistics with frequency analysis and simple mean, Chi-square test and correspondence analysis (Hair et al., 2006).

The data analyses used in this research work are descriptive and inferential statistical and descriptive analysis applied to measure the frequency distribution and location measures of data for all demographic variables of SHGs. The simple mean is again a commonly used measure indicating central tendency such as ranking the priorities of training. Analysis of variance is a statistical tool which is used to compare if two means are equal or differ. The Duncan method is used as post-hoc analysis. The analysis of variance has been used to find the impact of the SHGs profile variables with the factored variables of training to SHGs. The significance level of less than 0.05 indicates that the categories of independent variables differ on the mean variables. Chi-square test is categorized as a non-parametric test. In this study, the chi-square test is used as a test of independence to determine if the two attributes are associated without indicating the direction or strength of relationship. Chi-square test of independence is used to find the association between SHG profile variables and variables of training of SHGs and the correspondence analysis provides a pictorial representation of the association between different categories of two variables. In this study, correspondence analysis has also been used to find the association between SHG profile variables and variables of training to SHGs.

Results and Discussion

Number of Persons with Formal Training

Training is a basic requirement to develop skill and involve in production activities by the microenterprises.The group members have undergone training to varied extents and in varying numbers. The higher number of persons who have undergone training gives increased intensity of production activity. More skills also contribute to different product types leading to higher output and greater quality of output. The categories of options given in this study are no training, one person, two persons, three persons and four and greater persons who have undergone training.

From Table 1, it can be inferred that a majority of the groups (29.9%) have two persons who have undergone formal training in some activity, while a good proportion of groups (22.7%) have no members who have undergone any formal training. A good proportion (18.3%) of the groups have four and more members who have undergone formal training and 15.1% of the groups have three members who have undergone formal training and a small proportion of the groups which is 13.9% have one person who has undergone formal training. Therefore, it can be said that a majority have undergone formal training.

Type of Organization that Provided Training

The training for the group members have been given by many organizations. These training sessions have been organized for the development of skills within the group such that the members are in a position to undertake entrepreneurial activities. The organizations involved are both governmental and non-governmental by nature. These organizations have identified several areas where skill development is required for the members. The categories shown are NGOs, banks, government and private institutions.

From Table 2, it can be inferred that a majority of the groups (57.8%) have been provided training by an NGO in different areas of skill development. A reasonable proportion of the groups consisting of 15.9% have helped each other in self training; a reasonable proportion of the groups (13.5%) have been trained through government institutes, such as, Krishi Vignan Kendras. A low proportion (6.4%) have been trained through bank training institutes and a similar proportion of groups have been trained through private institutes which are largely in the area of tailoring.

Amount Willing to Pay for Training

Training involves several costs which are incurred by the training institutes. Therefore, these training are being undertaken only on a periodic basis. Some of the organizations have been able to provide the training free of cost to the groups, but in many circumstances the organizations charge fees for the training conducted. The amount of fees that the organization requires needs to be matched by the amount that the groups are willing to pay. In this study, the five categories of amounts the groups are willing to pay and the frequency of their responses have been provided in Table 3.

From Table 3, it can be inferred that the majority of the groups (47.4%) of SHGs are willing to pay up to 1,000 to undergo training. A good proportion (28.7%) of the groups are not willing to pay any amount. A reasonable proportion of the groups (13.9%) are willing to pay between 1,001 to 2,000. A small proportion of 6% of the groups are willing to pay 2,001 to 3,000 and a similar small proportion of the groups (4%) are willing to pay 3,001 and greater for skill development. Therefore, it can be concluded that the majority of the groups are in a position to pay up to 1,000 to undergo training.

Priorities of Training

Training for SHGs has become an important aspect for skill improvement to enable SHG members to produce products regularly and to the desired quality and quantity. The opinions presented as mean values pertaining to willingness to undergo training and the feedback from training programs are provided in Table 4.

Table 4 shows the group's opinion on ability to produce new products with new training, which shows mean value at 4.47 and which indicates high confidence in training to produce new products. This indicates that most SHGs are very confident of producing new products after training. The second aspect of training depicts a mean value of 4.39 representing the need for training to produce products which indicates that training is compulsory. The third ranked aspect is 'need different types of training' indicating a mean rank of 4.26. The overall feedback is fourth ranked with a score of 4.22 indicating good positive feedback on quality of training and lastly if organizations are providing training shows a value of 3.86, which indicates that more organizations should be involved in providing training.

Since p-value is less than 0.01, that there is significant difference between type of affiliating institutions and number of training undergone by group is empirically found. Based on the row and column percentage, it can be inferred that 33% of the SHGs affiliated to NGOs have undergone two trainings, 35% of the SHGs affiliated to cooperative banks have undergone four trainings, 48% of the SHGs affiliated to public sector banks have undergone two trainings, and 65% of the SHGs who have undergone more than four trainings are affiliated to NGO.

Type of Organization That Provided Training

Chi-square test results for association between type of affiliating institution and type of organization provided training are shown in Table 11.

Since p-value is less than 0.01, that there is significant difference between type of affiliating institutions and type of organization that provided training is empirically tested. Based on the row and column percentage, it can be inferred that 35% of the SHGs affiliated to cooperative banks have been trained by government institutes, 48% of the SHGs affiliated to public sector banks have been provided training through NGOs, 47% of the groups affiliated to municipality have been trained through government institutes.

Correspondence Analysis

Number of Persons with Formal Training

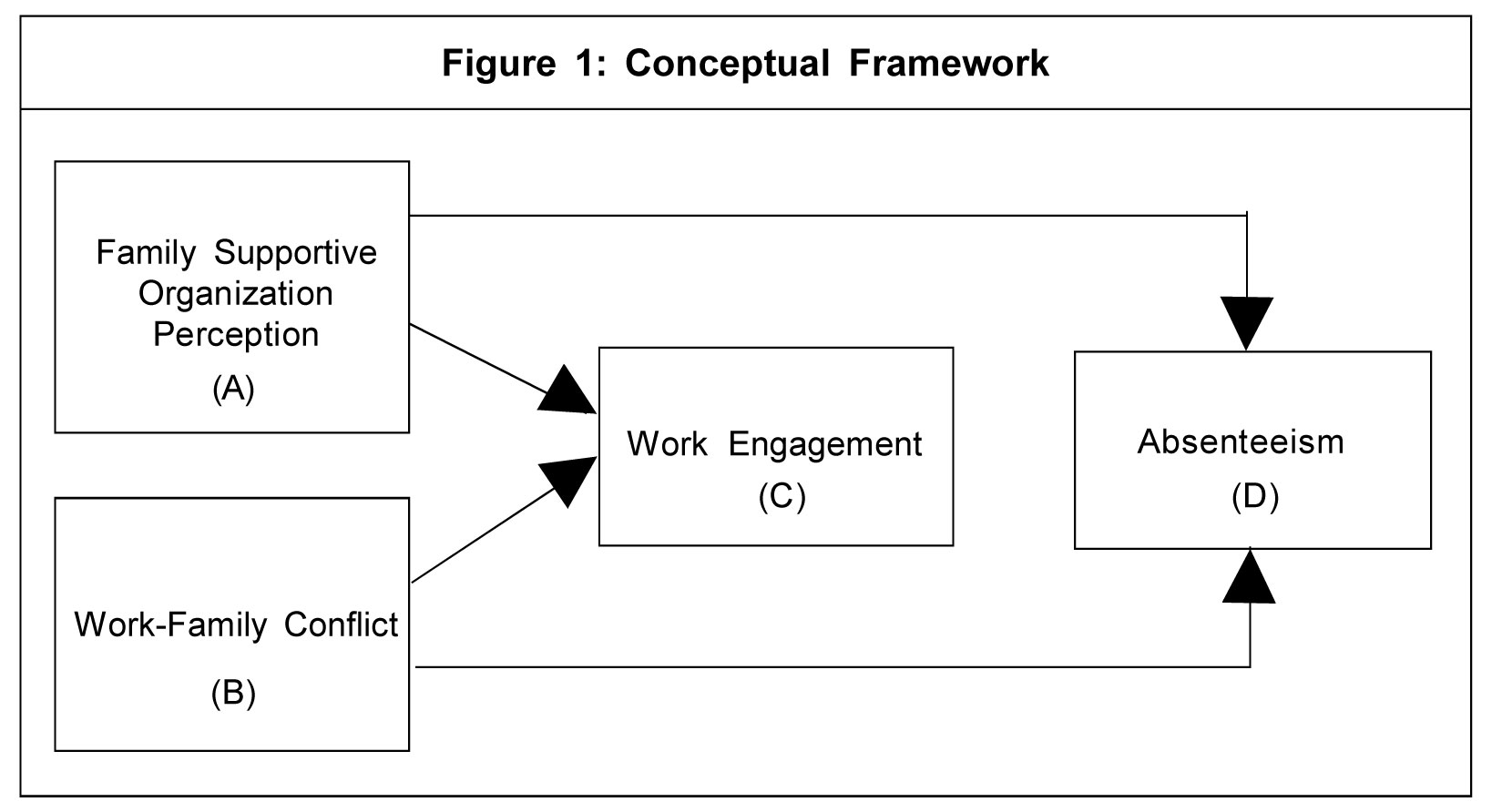

To find the association between number of years of functioning of the groups and number of persons with formal training, a chi-square test was done which showed a significant association between the two indicators with a significance level of 0.002. A correspondence analysis of the association is provided in Figure 1.

It can be inferred from Figure 1 that groups below 1 year of functioning and

1-2 years of functioning are associated with nil or no persons with formal training. There is association between groups functioning above four years and with one person and three persons having formal training. There is also association between groups functioning for 2-3 years and two persons with formal training, and there is association between functioning for 3-4 years and four and more persons with formal training.

Number of Trainings by Group

To find the association between number of years of functioning of the groups and number of trainings undergone by the group, a chi-square test was done which showed a significant association between the two indicators with a significance level of 0.003. Further, a correspondence analysis chart of the association is provided in Figure 2.

From Figure 2, it can be inferred that there is association between below 1 year and no training; there is association between 1-2 years and one training; there is association between 2-3 years functioning and two formal training and three formal trainings; and there is association between 3-4 years and four and greater formal trainings.

Amount Willing to Pay for Trainings by Groups

To find out the association between number of years of functioning of the groups and amount willing to pay for training, chi-square test was performed which showed a significant association between the two indicators with a significance level of 0.008. Further, a correspondence analysis to depict the association is provided in

Figure 3.

From Figure 3, it can be inferred that there is an association between below 1 year and no amount and up to 1,000. There is association between 1-2 years and 1,001 to 2000. There is association between 2-3 years and 2,001-3,000. There is an association between 3-4 years and 3,001 and greater.

Number of Trainings Undergone By The Group

To find the association between type of affiliating institutions and number of training undergone by the group, a chi-square test was done which showed a significant association between the two indicators with a significance level of 0.002. A correspondence analysis of the association is provided in Figure 4.

From Figure 4, it can be inferred that there is an association between the NGOs and three and four trainings; there is a close association between cooperative banks and one training; there is an association between public sector banks and two trainings; and there is an association between municipality and no training.

Conclusion

A majority of the groups (29.9%) have two persons who have undergone formal training in some activity, while a good proportion of groups (22.7%) have no members who have undergone any formal training. A majority of the groups (57.8%) have been provided training by an NGO in different areas for skill development. A majority of the groups (47.4%) of SHGs are willing to pay up to 1,000 to undergo training. A good proportion (28.7%) of the groups are not willing to pay any amount.

SHGs' ability to produce new products with new training shows the mean value at 4.47 and has been ranked as first of the two aspects of training, which itself indicates high confidence in training to produce new products. The second aspect of training depicts a mean value of 4.39 representing 'need training to produce products', which indicates that training is compulsory. ANOVA test results show that there is a significant difference between numbers of years of functioning with respect to training activity and significant difference between type of affiliating institutions and training.

Chi-square test results show that there is an association between type of affiliating institution and number of members with formal training. Based on the row and column, it can be inferred that 35% of the SHGs affiliated to NGOs have two members with formal training, 47.1% of the SHGs affiliated to cooperative banks have four and greater members with formal training, and there is an association between the type of affiliating institution and number of trainings undergone by the group. Based on the row and column percentage, it can be inferred that 33% of the SHGs affiliated to NGOs have undergone two trainings, 35% of the SHGs affiliated to cooperative banks have undergone four trainings, and 48% of the SHGs affiliated to public sector banks have undergone two trainings. There is association between type of affiliating institution and type of organization that provided training. Based on the row and column percentage, it can be inferred that 35% of the SHGs affiliated to cooperative banks have been trained by the government institutes.

Correspondence analysis results show that groups below 1 year of functioning and

1-2 years of functioning are associated with nil or no persons with formal training. There is an association between groups functioning above four years with one person and three persons having formal training. There is also association between groups functioning for 2-3 years and two persons with formal training. There is an association between below 1 year and no training. There is an association between 1-2 years and one training. There is an association between 2-3 years functioning and two formal training and three formal trainings. There is an association between 3-4 years and four and greater formal trainings and also an association between NGOs and three and four trainings. There is close association between cooperative banks and one training. There is an association between public sector banks and two trainings, and there is an association between municipality and no training.

Implications: The paper endeavors to study the various distribution activities performed by the SHGs in the Union Territory of Puducherry. The study will be a useful guide for making strategic decisions for the development of SHGs. Thus, this study will be of immense utility to the government, banks, microfinance organizations and other policy makers. The study provides inputs for academic thought and understanding of certain theoretical aspects and methods of approach to research issues and also implications for training activities of SHGs. Formal skill training certificates from SHG members for bank loans can be linked for better performance of the groups. More so, training charges for such training could be used from the loan amount itself to pay for the required skill development training. Since training is greater in SHGs affiliated to banks, bank-sponsored training centers should be made mandatory for all the banks by introducing corporate social responsibility clause in banks. Since a sizable proportion of the groups work in hired places for production operations, common facilities centers providing common space for operations and commonly used machines provided on rent could be provided by the government's financial support and such a space facility could also be used for providing training for the SHG development.

References

- Arokiaraj David R R A, Ganeshkumar C and Jeganthan Gomathi Sankar (2020a), "Consumer Purchasing Process of Organic Food Product: An Empirical Analysis", Quality: Access to Success, Vol. 21, No. 177, pp. 128-132.

- Arokiaraj D, Ganeshkumar Chandirasekaran and Victer Paul (2020b), "Innovative Management System for Environmental Sustainability Practices Among Indian Auto-Component Manufacturers", International Journal of Business Innovation and Research, Vol. 23, No. 2, pp. 168-182.

- Basargekar P (2008), "Economic Empowerment Through Microfinance: An Assessment of CSR Activity Run by Forbes Marshall Ltd.", International Journal of Business Insights & Transformation, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 23-42.

- De Mel S, McKenzie D and Woodruff C (2009), "Are Women More Credit Constrained? Experimental Evidence on Gender and Microenterprise Returns", American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, Vol. 1, No. 3, pp. 1-32.

- Ganesh Kumar C, Murugaiyan P and Madanmohan G (2017), "Agri-Food Supply Chain Management: Literature Review", Intelligent Information Management, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 68-96.

- Ganeshkumar C and Mohan G M (2014), "Data Assumptions Checking for Estimating Structural Equation Modeling: Supply Chain Context", Anvesha, Vol. 7, No. 4, p. 12.

- Ganeshkumar C and Nambirajan T (2013), "Supply Chain Management Components, Competitiveness and Organisational Performance: Causal Study of Manufacturing Firms", Asia-Pacific Journal of Management Research and Innovation, Vol. 9, No. 4, pp. 399-412.

- Ganeshkumar C, Mohan G M and Nambirajan T (2014), "Multi-Group Moderating Effect of Goods Produced in the Manufacturing Industry: Supply Chain Management Context", NMIMS Management Review, Vol. 15, No. 2, pp. 1-21.

- Ganeshkumar C, Prabhu M and Abdullah N N (2019), "Business Analytics and Supply Chain Performance: Partial Least Squares-Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Approach", International Journal of Management and Business Research (IJMBR), Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 91-96.

- Hair J F, Black W C, Babin B J et al. (2006), Multivariate Data Analysis, Vol. 6, Pearson Prentice Hall Upper Saddle River, NJ.

- Heilman M E and Chen J J (2003), "Entrepreneurship as a Solution: The Allure of Self-Employment for Women and Minorities", Human Resource Management Review, Vol. 13, No. 2, pp. 347-364.

- Jamshi J and Ganeshkumar C (2017), "Causal Linkage Among Business Analytics, Supply Chain Performance, Firm Performance and Competitive Advantage", Parikalpana: KIIT Journal of Management, Vol. 13, No. 2, pp. 29-36.

- Joy L, Prema A and Krishnan S (2008), "Determinants of Group Performance of Women-Led Agro-Processing Self-Help Groups in Kerala", Agricultural Economics Research Review, Vol. 21 (Conf.), pp. 355-362.

- Kanitkar A (1994), "Entrepreneurs and Micro-Enterprises in Rural India", Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 29, No. 9, pp. 30-37.

- Kumar C G and Nambirajan T (2013), "Supply Chain Management Concerns in Manufacturing Industries", IUP Journal of Supply Chain Management, Vol. 10, No. 4, pp. 69-82.

- Kumar S (2010), "SHG-Linked Microcredit in Kerala-A Micro-Scan of Prospects and Problems of Kudumbashree Linked Microenterprises", Macro Dynamics of Microfinance, Vol. 1, No. 2, pp. 335-342.

- Madlani M B (2009), "Women Entrepreneurship and Rural Development", Abhinav Journal, Vol. 12, No. 2, pp. 94-98.

- Midgley J (2008), "Microenterprise, Global Poverty and Social Development", International Social Work, Vol. 51, No. 4, pp. 467-479.

- Paul P V, Ganeshkumar C, Dhavachelvan P and Baskaran R (2020), "A Novel ODV Crossover Operator-Based Genetic Algorithms for Traveling Salesman Problem", Soft Computing, Vol. 35, No. 6, pp. 1-31.

- Paul V, Ganeshkumar C and Jayakumar L (2019), "Performance Evaluation of Population Seeding Techniques of Permutation-Coded GA Traveling Salesman Problems Based Assessment: Performance Evaluation of Population Seeding Techniques of Permutation-Coded GA", International Journal of Applied Metaheuristic Computing (IJAMC), Vol. 10, No. 2, pp. 55-92, doi: 10.4018/IJAMC.2019040103

- Rishikesh P and Ganeshkumar C (2016), "Brand Extension Strategy - Literature Review and Conceptual Model Development", ASBM Journal of Management, Vol. 7, No. 1, pp. 1-13.

- Siddhartha T, Nambirajan T and Ganeshkumar C (2017a), "Outsourcing Decision of Micro-Small-Medium Enterprises (MSME)", Pragyaan: Journal of Management, Vol. 15, No. 1, pp. 23-28.

- Siddhartha T, Nambirajan T and Ganeshkumar C (2017b), "Distribution Methods Adopted for Self-Help Group Products: An Empirical Analysis", IUP Journal of Operations Management, Vol. 16, No. 4, pp. 25-33.

- Siddhartha T, Nambirajan T and Ganeshkumar C (2019), "Production and Retailing of Self help Group Products", Global Business and Economics Review, Vol. 21, No. 6, pp. 814-835, doi: 0.1504/GBER.2019.102590.

- Sooryamoorthy R (2007), "Microcredit for Microenterprises or for Immediate Consumption Needs?", Sociological Bulletin, pp. 401-413.

- Ssewamala F M and Sherraden M (2004), "Integrating Saving into Microenterprise Programs for the Poor: Do Institutions Matter?", Social Service Review, Vol. 78, No. 3, pp. 404-428.

- Swain R B and Varghese A (2009), "Does Self Help Group Participation Lead to Asset Creation?", World Development, Vol. 37, No. 10, pp. 1674-1682.

- Swain R B and Wallentin F Y (2009), "Does Microfinance Empower Women? Evidence from Selfhelp Groups in India", International Review of Applied Economics, Vol. 23, No. 5, pp. 541-556.

- Thyagarajan S, Nambirajan T and Chandirasekaran G (2018), "Help Financial Operations and Product Preferences of Self Help Groups (SHG)", SJCC Management Research Review, Vol. 8, No. 1, pp. 20-32.

- Thyagarajan S, Nambirajan T and Chandirasekaran G (2019), "Retailing of Self-help Group (SHG) Products in India", Journal of Applied Business and Economics, Vol. 21, No. 5, pp. 128-138.

- Thyagarajan S, Thangasamy N and Chandirasekaran G (2018), "Legal Requirements for Linking Self-Help Groups to Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises", IUP Law Review, Vol. 8, No. 2, pp. 33-42.

- Tinker I (2003), "Street Foods: Traditional Microenterprise in a Modernizing World", International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society, Vol. 16, No. 3, pp. 331-349.

- Tsai K S (2000), "Banquet Banking: Gender and Rotating Savings and Credit Associations in South China", The China Quarterly, Vol. 161, No. 2, pp. 142-170.