July '22

The IUP Journal of Organizational Behavior

Archives

Experience of Occupational Stress Across Gender and Professional Characteristics of University Teachers in India

Dharitri Baishya

Research Scholar, Department of Commerce, North-Eastern Hill University, Shillong, Meghalaya, India;

and is the corresponding author. E-mail: dharu.ninsu@gmail.com

Nagari Mohan Panda

Professor, Department of Commerce, North-Eastern Hill University, Shillong, Meghalaya, India.

E-mail: nagaripanda@yahoo.com

Teachers are the major drivers of a nation's education system and hence require a stress-free working environment to perform at their best. The current study aims to examine occupational stress among university teachers' based on their gender and professional characteristics. This study also attempts to identify the sources of occupational stress across various other characteristics of the teachers. A sample of 536 teachers participated in the study selected from six universities in Assam, India. Data was collected through a self-administered questionnaire-based survey. The major findings of this study indicate the presence of a significant difference in the occupational stress level across the academic position, but not in gender and academic discipline. As regards stress sources, there is a significant difference in 10 out of 20 stressors according to academic positions. The results also show a significant difference across gender for only two sources and for seven sources when it comes to academic discipline. These insights would enable higher educational institutions to focus on adopting strategies to reduce or eliminate the influence of the stressors based on gender and professional characteristics of teachers.

Introduction

Stress has become a highly emotional issue in the day-to-day lives of people. The concept of stress was initially borrowed from the field of Physics, where it is denoted as an external force on an object causing a change in its shape. Hans Selye, also known as the father of stress research, incorporated this term into medical science in 1936 and defined it as the "nonspecific response of the body to any demand" (Selye, 1956). Stress research later expanded to encompass cognitive processes to describe how individuals react to normal and unusual circumstances in daily life. From a psychological perspective, stress is a specific interaction between people and their environment that is regarded as challenging or surpassing coping capacities (Lazarus, 1966). In the organizational context, stress is also acknowledged by the terms such as job stress, occupational stress, or workplace stress. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), a US research agency on workers, defined occupational stress as the detrimental physical and emotional responses that arise when the job requirements do not meet the worker's skills, resources, or needs (NIOSH, 1999). The substantial change in the economy brought in by globalization and the global financial crisis has resulted in a mounting stress level in workplaces due to increasing demand on workers (International Labor Organization, 2016). According to the latest research conducted by the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) in 2020, stress, anxiety, and depression accounted for around 51% of all work-related ill-health cases and 55% of all working days missed due to work-related ill-health among workers in the United Kingdom.

The education sector is one of the crucial human services sectors, where employees are required to deal directly with human beings and remain physically and emotionally engaged. Six occupations out of 26 in UK, including ambulance workers, police, social services, prison officers, call centers, and teachers, scored the worst on comparing their occupational stress levels (Johnson et al., 2005). The teachers in the education sector are not far behind when it comes to the detrimental effect of occupational stress. Traditionally, Indian culture has held teachers in high regard and placed them in a special position; that is rapidly changing with the increasing expectations and new challenges faced by the teachers. The rise in the number of universities from only 28 to more than one thousand during the post-independence period of 1950-51 to 2019-20 has brought the teachers under considerable pressure (Tilak, 2021). In a study conducted in Indian universities, about 74% and 86% of the teachers reported experiencing moderate to high occupational stress and professional burnout, respectively (Reddy and Poornima, 2012). The commercialization of the higher education sector has resulted in an overemphasis on efficiency and quantity rather than effectiveness and quality, academic freedom eroded by dictatorial management, intellectualism replaced by instrumentalism, an adversarial and aggressive working environment created by competition, and work intensification (Meng and Wang, 2018; and Tarbener, 2018). A large-scale empirical study compared occupational stress levels across nineteen higher education systems and found that the countries with strong market-oriented managerial reforms fall in the high-stress group (Shin and Jung, 2014). The new work environment, as a result, affects the mental wellbeing of the teachers and, in turn, influences their job performance (Kazmi et al., 2008; and Devi and Lahkar, 2021), work commitment (Barkhuizen and Rothmann, 2008), job satisfaction (Kinman, 2016; and Han et al., 2021), turnover intention (Hoyos and Serna, 2021), work-life balance (De Paula and Boas, 2017), and at times cause burnout in them (Reddy and Poornima, 2012).

As reported by ILO (2016), most occupational stress research is conducted in Europe, North America, and other developed nations, but to a limited extent in Latin America and Asia-Pacific regions. When it comes to educational professionals in a university setting, occupational stress studies are mainly concentrated in countries such as the United States (Gmelch et al., 1986; Blix et al., 1994; Smit et al., 1995; Altbach and Boyer, 1996; Lease, 1999; Lindholm and Szelenyi, 2008; and Shin and Jung, 2014); UK (Kinman and Jones, 2003; Shin and Jung, 2014; Kinman, 2016; and Taberner, 2018); Australia (Gillespie et al., 2001; Winefield et al., 2002; Hogan et al., 2002; and Shin and Jung, 2014); China (Shin and Jung, 2014; Li and Kou, 2018; Meng and Wang, 2018; and Liu, 2020); and Japan (He et al., 2000; Kataoka et al., 2014; and Shin and Jung, 2014), etc. However, empirical investigations on occupational stress of the teachers in Indian universities are still limited to a few specific regions (Pestonjee and Azeem, 2001; Mittal and Purohit, 2012; Reddy and Poornima, 2012; Kang and Sidhu, 2015; and Zaheer et al., 2016; and Tiwari and Pant, 2017), other than the Northeast India regional settings, where no traceable scientific research on university teacher's occupational stress is found. Very few empirical research studies conducted scientifically exist, and further the results of these studies are not free from ambiguity and contradiction. The Northeast region is uniquely characterized by diverse geographical, economic, infrastructural, and cultural attributes. Therefore, we may assume a different pattern of occupational stress level among the teachers in this region compared to that of their counterparts in other areas of India. Founded on this premise, the current paper intends to examine the level of occupational stress of university teachers of Assam according to different gender and professional characteristics such as academic position, academic discipline, and gender. This study also sheds light on the sources of occupational stress experienced by the teachers according to their gender and professional characteristics.

Literature Review and Hypotheses Formulation

A wide range of research studies have been conducted on occupational stress globally with various objectives. In some studies, researchers have attempted primarily to identify the sources of occupational stress (Mittal and Purohit, 2012; Kang and Sidhu, 2015; Ismail and Noor, 2016; De Paula and Boas, 2017; and Meng and Wang, 2018), whereas others have tried to examine how occupational stress varies across different background variables of the individuals: gender, socioeconomic, or work-related (Herrero et al., 2012; Marinaccio et al., 2013; Shkembi et al., 2015; Jiang et al., 2018; and Faraji et al., 2019). Keeping in view the objective and scope of the current paper, an attempt is made here to succinctly present an overview of the extant literature on occupational stress that provides us with a theoretical understanding of the phenomenon and some empirical evidence on the relationship of occupational stress with gender and professional characteristics of the employees as the basis of our hypotheses.

Gender and Occupational Stress

Gender is considered one of the most focused areas of research in disciplines such as biology, sociology, and social psychology. Numerous theories have been developed to explain the differences in gender and their influence on the daily life activities of an individual. According to the Social Role Theory by Eagly (1987), males and females are assigned a few characteristics based on their discrepant social roles in the workplace and family life, which has given rise to the concept of gender stereotype. As females are involved more in caregiving, they are generally attributed to nurturing, caring, and feminine characteristics, thus termed communal in behavior. In contrast, males are expected to be agentic as they mostly work outside the home and possess masculine traits like independence and competence (Eagly and Wood, 1991). These differences in gender role beliefs have resulted in inequalities between females and males in the workplace, where females are perceived as illogical, emotional, intuitive decision-makers (Green and Cassell, 1996) and less skilled than males (Ely and Meyerson, 2000). The existence of gender hierarchies constrains females from formal authority and access to resources in organizations, known as the Glass Ceiling effect. Regardless of their qualifications or accomplishments, females in various occupations undergo discriminatory behavior toward achieving top managerial positions (Cotter et al., 2001). Moreover, as females possess more communal and less agentic qualities, they are perceived as less qualified for leadership roles than males (Eagly and Karau, 2002). On relating gender traits and social roles with health, research studies have found that individuals with masculine characteristics are associated with better health (Annandale and Hunt, 1990), whereas those with femininity are more prone to depression (Bromberger and Matthews, 1996).

A large number of empirical studies have supported the common finding of females experiencing a higher level of occupational stress as compared to their male counterparts (Matud, 2004; Antoniou et al., 2006; Kumar and Deo, 2011; Sliskovic and Sersic, 2011; Herrero et al., 2012; Marinaccio et al., 2013; Kachi et al., 2020; Liu, 2020; Bird and Rhoton, 2021). In congruity with traditional gender roles, females' responsibilities are extended beyond their work roles (Gotz et al., 2018), causing work-life conflict and increased workload (Beach, 1989; Jacob and Winslow, 2004; Antoniou et al., 2006; Kumar and Deo, 2011; and Sliskovic and Sersic, 2011). Females suffer from unfavorable social recognition and status compared to males (Sliskovic and Sersic, 2011; and Bird and Rhoton, 2021), apparent from their lesser occupancy in senior positions and lower academic productivity in the teaching profession (Bain and Cummings, 2000). Adoption of less problem-centered and more emotion-focused coping strategy (Matud, 2004), deadline pressure, complex and intellectually demanding tasks requiring a high level of attention (Herrero et al., 2012), and lack of control at work (Marinaccio et al., 2013) are the more stressful factors for females than males. A few studies have found higher occupational stress levels in males than females (Vakola and Nikolaou, 2005; Jiang

et al., 2018; and Faraji et al., 2019).

Under conventional family arrangements, males should be the main wage earners and control their jobs. Therefore, when male workers perceive insufficient reward and lack of control, they experience stress manifested in aggressive impulses towards the organization (Kim et al., 2018). Matters related to the financial realms (McDonough and Walters, 2001; and Matud, 2004), work relationships (Vakola and Nikolaou, 2005), and lack of social support (Jiang et al., 2018) are the stressors that males experience more intensely than females. A few other studies have reported no significant difference in the experience of occupational stress between females and males (Marinaccio et al., 2013; Shkembi et al., 2015; Prasad et al., 2016; Faraji et al., 2019; and Devi and Lahkar, 2021). The increased participation of females in employment and new educational arenas has led to a convergence in the perception of both males and females (Eagly and Wood, 2012), resulting in much more similarity in the appraisal of stressors in their working environment. Though previous research studies have shown an ambiguous picture of the relationship between gender and occupational stress, most researchers have depicted females as the most stressful group. Accordingly, we formulate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Female teachers perceive significantly more occupational stress as compared to male teachers.

Academic Position and Occupational Stress

The traditional hierarchical structure of organizations in the higher education system governed by the power distance culture may contribute to occupational stress among the employees engaged in this sector (Hofstede et al., 2005). Power distance is "the extent to which the less powerful persons in a society accept inequality in power and consider it normal" (Hofstede, 1986). In the higher education system, the teachers in higher positions enjoy organizational and social power. The amount of authority, autonomy, resources, and job security distinguish the three academic positions: the assistant professor, associate professor, and professor. These positions are associated with different stressors comprising varying levels of vulnerability (Sliskovic and Sersic, 2011).

Many researchers have observed an inverse relationship between occupational stress and employees' position in an organization. The employees placed in higher positions experience a lower level of occupational stress relative to those in lower positions (Pestonjee and Azeem, 2001; Winefield et al., 2002; Jacob and Winslow, 2004; Akbar and Akhter, 2011; Kumar and Deo, 2011; Kataoka et al., 2014; Meng and Wang, 2018; Jiang et al., 2018; and Liu, 2020). Studies have reported that academic position, age, and years of experience go together (Thorsen, 1996; Oshagbemi, 2003; Shkembi et al., 2015; and Li and Kou, 2018), and longer work experience mitigates the level of stress at higher positions (Thorsen, 1996). As a result, the younger employees with lower exposure and years of experience perceive higher stress levels than the older ones (Kumar and Deo, 2011). It is because autonomy, role awareness (Robertson and Tracy, 1998), adaptability (Scheibe et al., 2016; and Jiang et al., 2018), and competence level (Faraji, 2019) of an individual increase with increasing years of experience in their respective field of occupation. Further, as manifested in a wiser preference for emotion regulation techniques, emotion regulation competence could be a possible asset among older workers (Scheibe et al., 2016). It is evident from an empirical study that university professors experienced lower stress levels than associates and assistant professors due to their higher autonomy, sense of security, and power in the higher position (Sliskovic and Sersic, 2011). People at the top positions of an organization are confident of promotion prospects in the same or another organization. They have an unconditional attachment to the organization, resulting in lower calculative commitment (Marcoux et al., 2021).

The senior employees become independent, and their expectations of their supervisor and co-workers' support decrease with their career advancement. It sometimes lowers the quality of relationships with their supervisors and colleagues (Marinaccio et al., 2013). On the contrary, the younger employees working at lower levels suffer from role overload, role stagnation, and problems in intergender relations (Kumar and Deo, 2011). These younger employees are more likely to experience occupational stress due to the necessity to perform tedious tasks, the presence of severe competition, and their aspirations for success in their respective academic fields (Jiang et al., 2018). Similarly, a study conducted among university teachers reported that the assistant professors who have recently been awarded their doctorate and are embarking on an independent scientific career are under the greatest pressure compared to their counterparts in other groups (Sliskovic and Sersic, 2011).

Other studies on differences in occupational stress according to academic position have reported that although occupational stress is lesser at a higher position, no significant difference is found in the stress levels among the teachers in the intermediate and lower position (Thorsen, 1996; and Winefield and Jarrett, 2001). In line with this finding, an inverse u-shaped relationship between occupational stress and age is observed, with lower stress levels in the youngest and oldest workers and higher levels in the two middle-aged categories (Gotz et al., 2018). Likewise, another study found that teachers in the age group of 41 to 50 years are more prone to leave their jobs (Hoyos and Serna, 2021), with most of them in the middle level of the hierarchical organizational status. From the previous literature, it could be noted that most of the research studies on the relationship between occupational stress and academic position converge on a common finding that those in the lower positions mainly perceive a higher level of occupational stress. Given the outcome of the literature review, we are motivated to form the second hypothesis of the study as stated below:

Hypothesis 2: Teachers working in lower academic positions perceive a higher level of occupational stress than the teachers in higher academic positions.

Academic Discipline and Occupational Stress

The professional identities of teachers are spread across a diverse spectrum of disciplinary affiliations in a university setting. Biglan (1973) has developed a taxonomy of these disciplines by putting them into three clusters with binary classification, namely, "hard" and "soft," "life" and "nonlife" and "pure" and "applied" . Accordingly, eight (23) disciplines emerge on sub-categorization (hard-nonlife-pure, hard-life-pure, soft-nonlife-pure, soft-life-pure, hard-nonlife-applied, hard-life-applied, soft-nonlife-applied, and soft-life-applied). Studies have applied this model to examine the differences in these disciplines and their associations with occupational stress (Gmelch et al., 1986; Perlberg and Keinan, 1986; Brown et al., 1986; Neuman and Finaly, 1990; Smith et al., 1995; Barnes et al., 1998; Lindholm and Szelenyi, 2008; and Doberneck and Schweitzer, 2017) empirically. The hard fields such as physics and biology are at the top level of the hierarchy, whereas soft areas such as education and sociology are at the bottom. Disciplines such as modern physics and biology are resource-rich areas where the teachers are engaged more in research work and less in teaching. Teachers in resource-poor disciplines such as humanities and social sciences apportion greater time to teaching. Thus, the teachers in diverse academic disciplines are engaged in different activities with different intensities and degrees of engagement (Doberneck and Schweitzer, 2017), resulting in variations in the stressors associated with these activities across the disciplines.

Although there are studies that have found no significant difference in occupational stress levels (when considering all the stress factors together) across academic disciplines (Thorsen, 1996; Winefield and Jarrett, 2001; and Meng and Wang, 2018), a significant difference is observed for a few of the stress factors (Gmelch et al., 1986; Perlberg and Keinan, 1986; Smith et al., 1995; Winefield et al., 2002; and Berebitsky and Ellis, 2018). Out of five stress factors examined in the study by Gmelch et al. (1986), only two factors, namely, reward and recognition and student interaction, showed significant differences across disciplines. Stress from reward and recognition is higher in soft, pure, nonlife (e.g., English, history, philosophy) disciplines as compared to hard, pure, nonlife (e.g., astronomy, chemistry, physics), the hard, applied, life (e.g., agriculture), and the soft, applied, nonlife (e.g., accounting, economics) disciplines. Moreover, stress from student interaction is more for hard, applied, nonlife (e.g., computer science, engineering), the soft, pure, life (e.g., anthropology, political science), the soft, applied, nonlife (e.g., accounting, economics), and the soft, applied, life (e.g., education) disciplines as compared to both the hard, pure, life (e.g., botany, physiology) and the hard, applied, life (e.g., agriculture) disciplines (Gmelch et al., 1986). In another study, stress from role overload is found higher in nonlife fields such as maths, engineering, English, and accounting than in pure-life fields such as botany, zoology, psychology, etc. (Brown et al., 1986). Similarly, task-based stress arising from workload, insufficient time, too many meetings, and frequent interruptions are more in soft applied life (e.g., education and education administration) disciplines relative to hard pure life (e.g., botany, physiology, and zoology) and soft pure nonlife (e.g., English, history, and philosophy) disciplines (Smith et al., 1995).

Time spent in teaching is more stressful in hard nonlife pure fields (e.g., chemistry, physics, maths) as compared to their counterparts in the soft nonlife applied (e.g., economics), the soft life applied (e.g., education), and the soft nonlife pure (e.g., English) disciplines. In contrast, time spent in research causes more stress for all hard fields except computer science, engineering, and related nonlife applied areas (Lindholm and Szelenyi, 2008). Interestingly, a few other studies found that teachers in humanities experience more stress from research than in the science discipline (Perlberg and Keinan, 1986; Thorsen, 1996; and Berebitsky and Ellis, 2018). According to a recent study conducted in the universities of China, teachers in the medical discipline had the greatest degree of occupational stress, followed by teachers in law, pedagogy, engineering, and science. Moderate pressure was reported by teachers in literature (including art), history, agronomy, economics, and management, whereas teachers in the field of philosophy expressed the lowest level of occupational stress (Liu, 2020). Likewise, another study in a similar country context reported that engineering, agriculture, and forestry teachers are less stressed than teachers in other disciplines. Engineering, agriculture, and forestry are intuitive topics, but liberal arts and science demand more imagination and active thought. Teaching and research on life and the human body are more complicated and abstract for medical teachers (Li and Kou, 2018). Therefore, previous studies clearly show a mixed result regarding the association of teachers' occupational stress with their academic discipline. Hence, we posit a nondirectional relationship between the two, which is stated hereunder:

Hypothesis 3: The occupational stress level of university teachers remains independent of their academic discipline.

Methodology

The sample of this study comprises 536 teachers drawn from six universities (two universities selected from each of the central, state, and private categories) in the state of Assam. These six universities are Assam University, Tezpur University, Gauhati University, Dibrugarh University, Assam Don Bosco University, and Kaziranga University. The data has been collected through a self-administered questionnaire-based survey with a 97% overall response rate (97% for central, 98% for state, and 99% for private universities). The two oldest universities are selected from each of the three university categories. A minimum of one-third of the total population from each university is selected for adequate representation. The professors, associate professors, and assistant professors, those who are recruited on a permanent basis, are selected from each of the academic departments on a random basis.

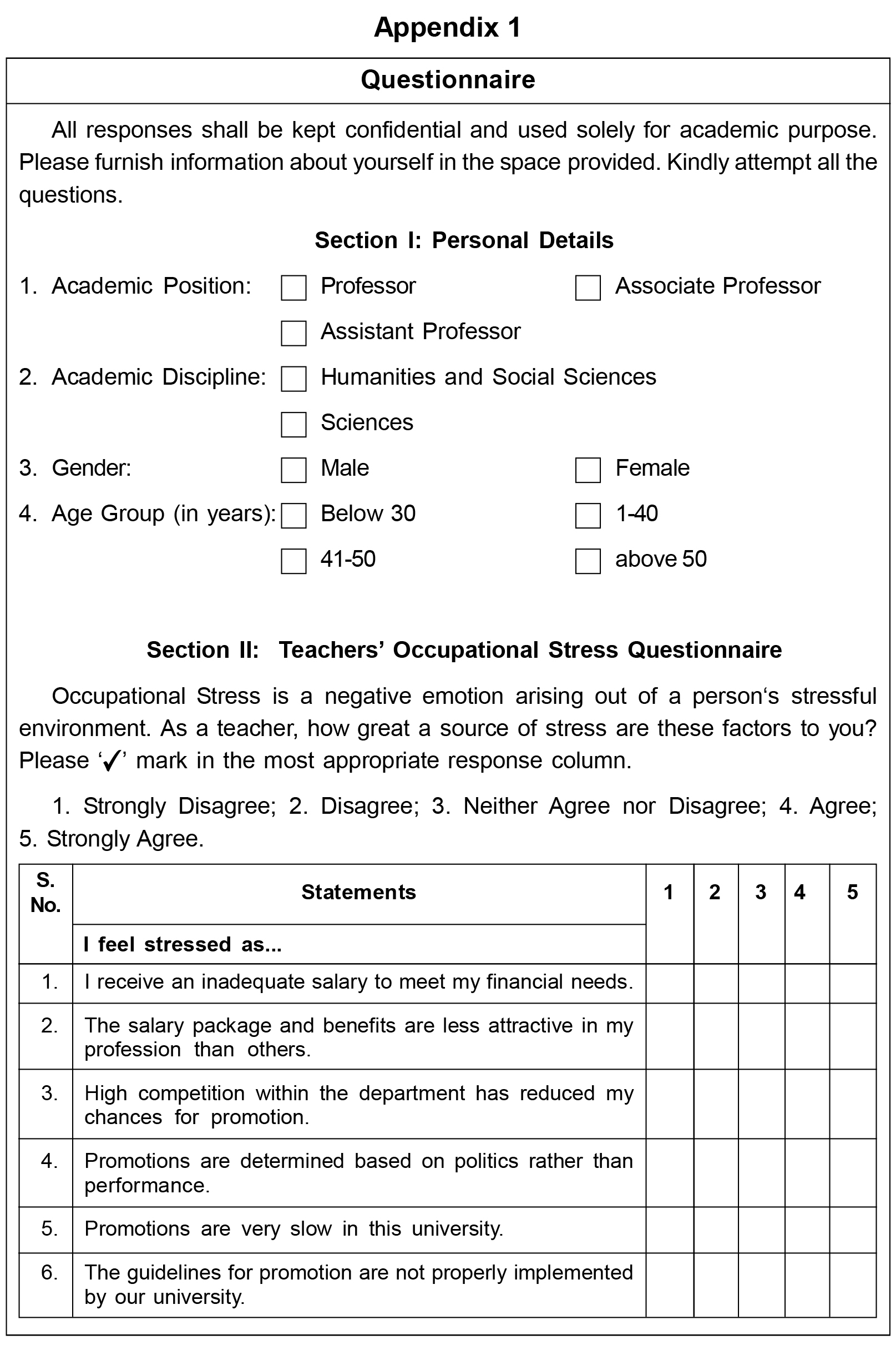

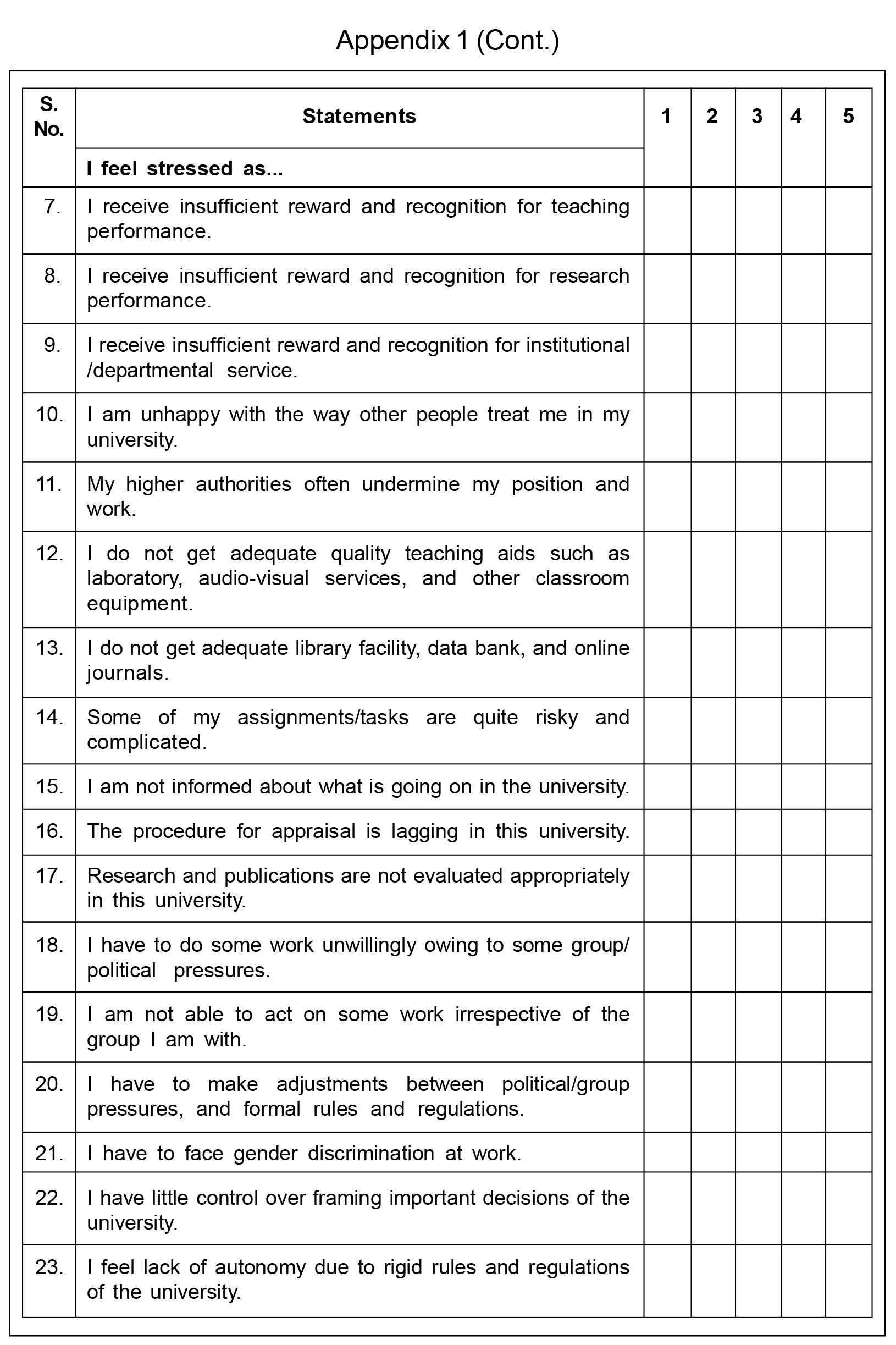

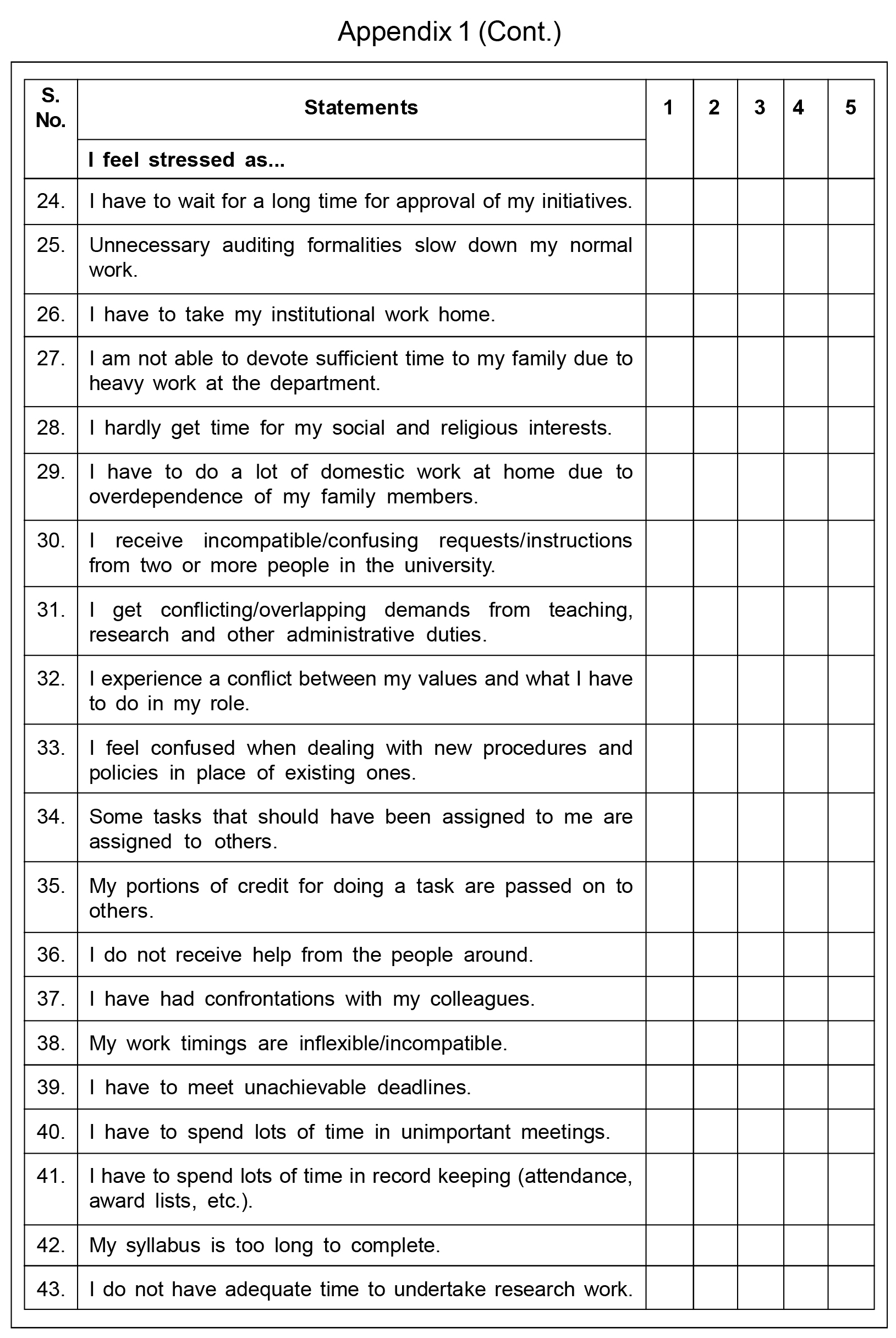

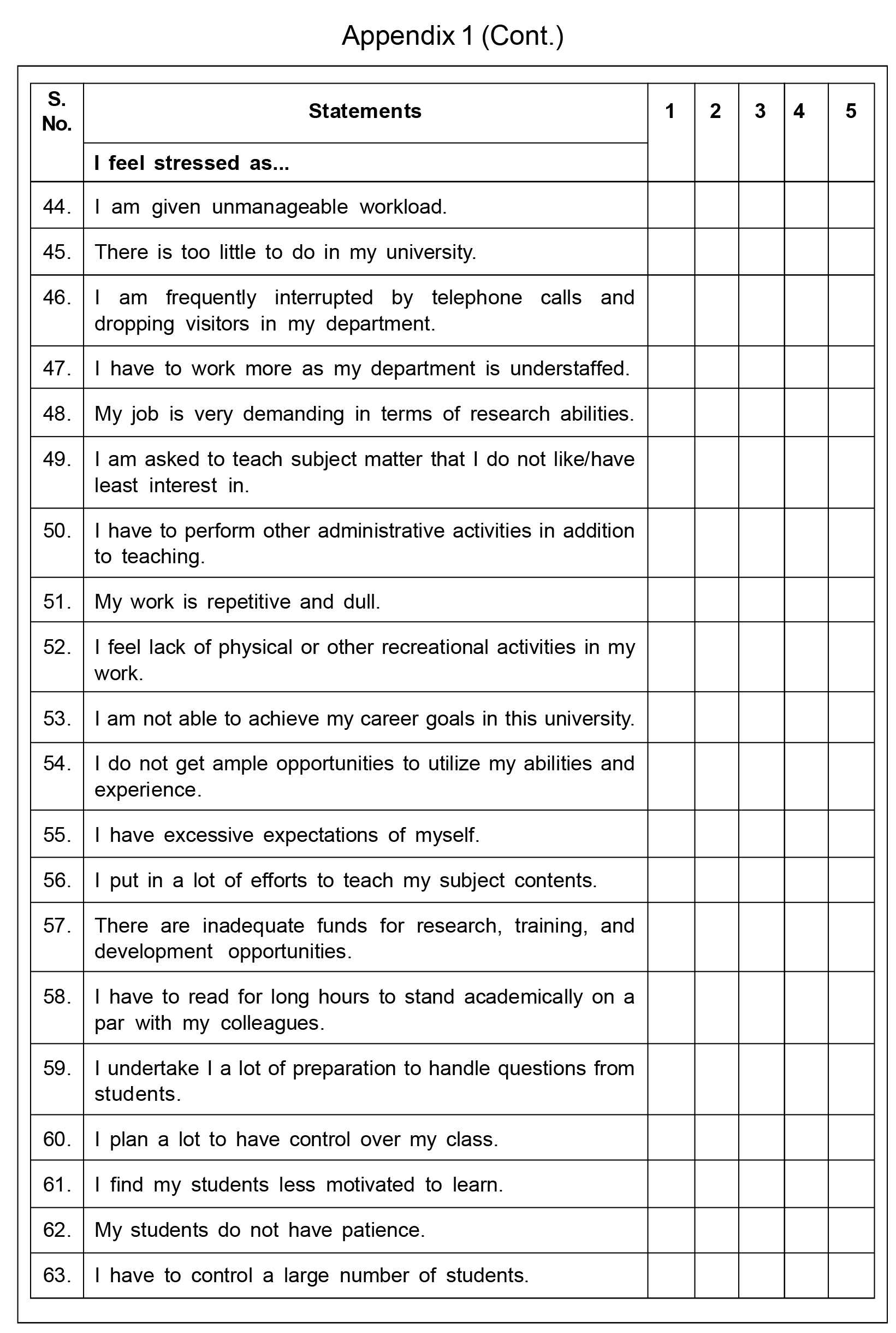

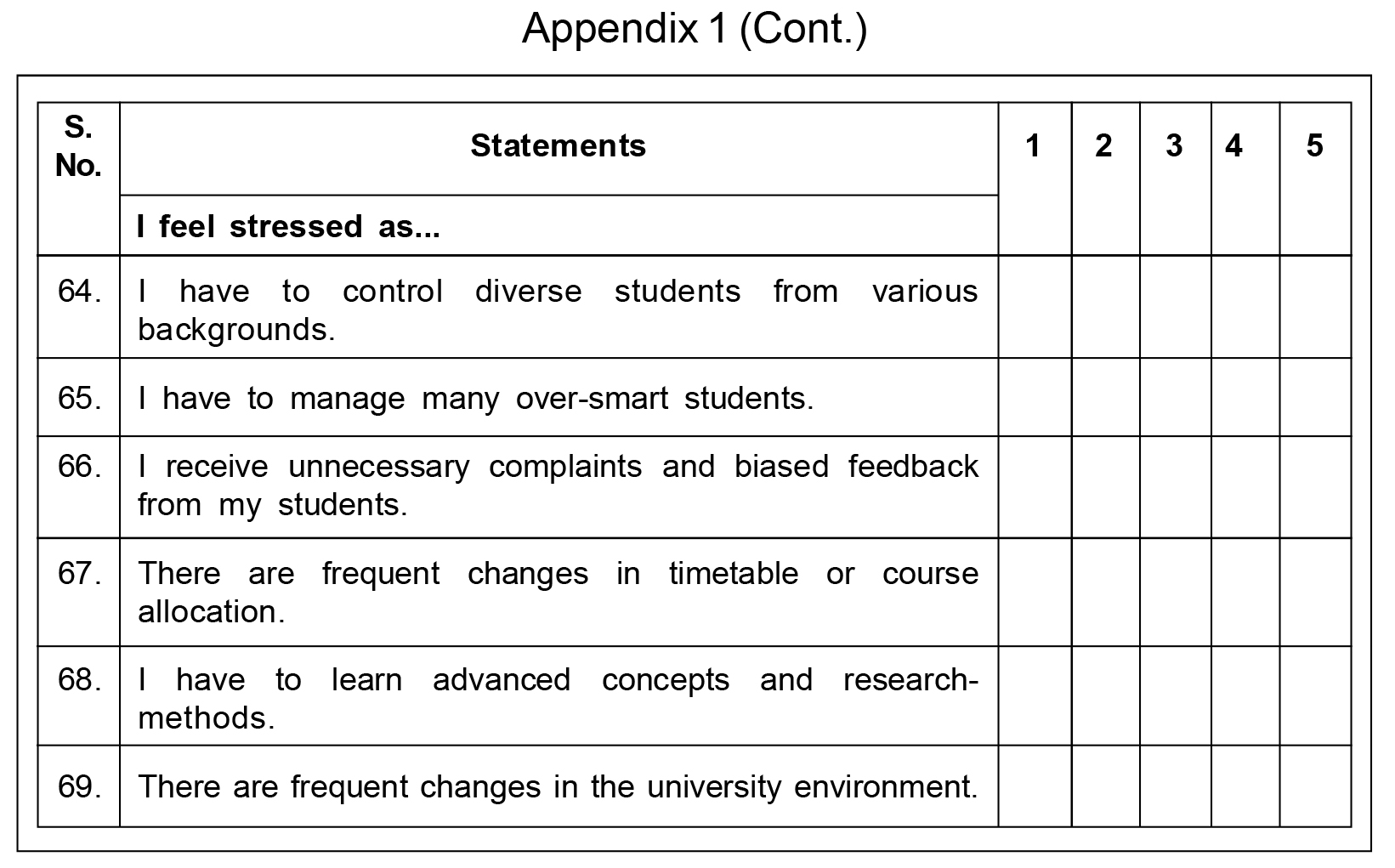

In the current study, occupational stress is measured as a subjective response of the teachers towards various factors existing in their surrounding environment that is perceived as having a negative impact on them. The first section of the questionnaire captures information on the gender and professional characteristics of the teachers, including academic position and academic discipline. The second section includes statements on work-related factors causing occupational stress in teachers. Data on teachers' occupational stress is obtained using a 69-item questionnaire (see Appendix 1) marked on a 5-point Likert scale, with 1 indicating strongly disagree and 5 strongly agree. The occupational stress statements are related to salary, promotion, reward and recognition, low status in the university, funding and support services, poor management, lack of control, formalities, role conflict, role erosion, workplace politics, relationships at work, time constraints, workload, the job itself, career development, poor competence of the teacher, student-related issues, change in the workplace, and homework interface. For designing these statements, the study has considered the tools advocated by earlier researchers, including Occupational Stress Index (OSI) by Srivastava and Singh (1981), Faculty Stress Index (FSI) developed by Gmelch et al. (1986), and the Stress tool for university teachers by Kinman and Jones (2003).

Occupational stress is the dependent variable, whereas teachers' gender and professional characteristics are considered the independent variables in the present study. The statistically significant difference in the level of occupational stress according to gender and professional characteristics has been analyzed by deploying Mann-Whitney U test (for comparing the means of two sample groups), and Kruskal-Wallis H test (for comparing the means of more than two sample groups), and the results are interpreted at 5% level of significance. The Mean Ranks (MR) are compared to explore the major stress sources across the academic position, academic discipline, and gender groups. Non-parametric tests are explored since the data did not fit a normal distribution. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov (p < 0.05) and Shapiro-Wilk (p < 0.05) tests are used to determine if the data is normal. It is pertinent to declare that the questionnaire was initially pilot tested with 100 teachers, and based on their input, the final questionnaire was designed with the required modifications. To test the internal consistency of the overall questionnaire and each stress factor, Cronbach's alpha (a) is computed. The result shows a = 0.96 for the overall occupational stress questionnaire and a ranging from 0.50 to 0.96 for each of the 20 stress factors.

Results and Discussion

Descriptive Statistics of the Teachers

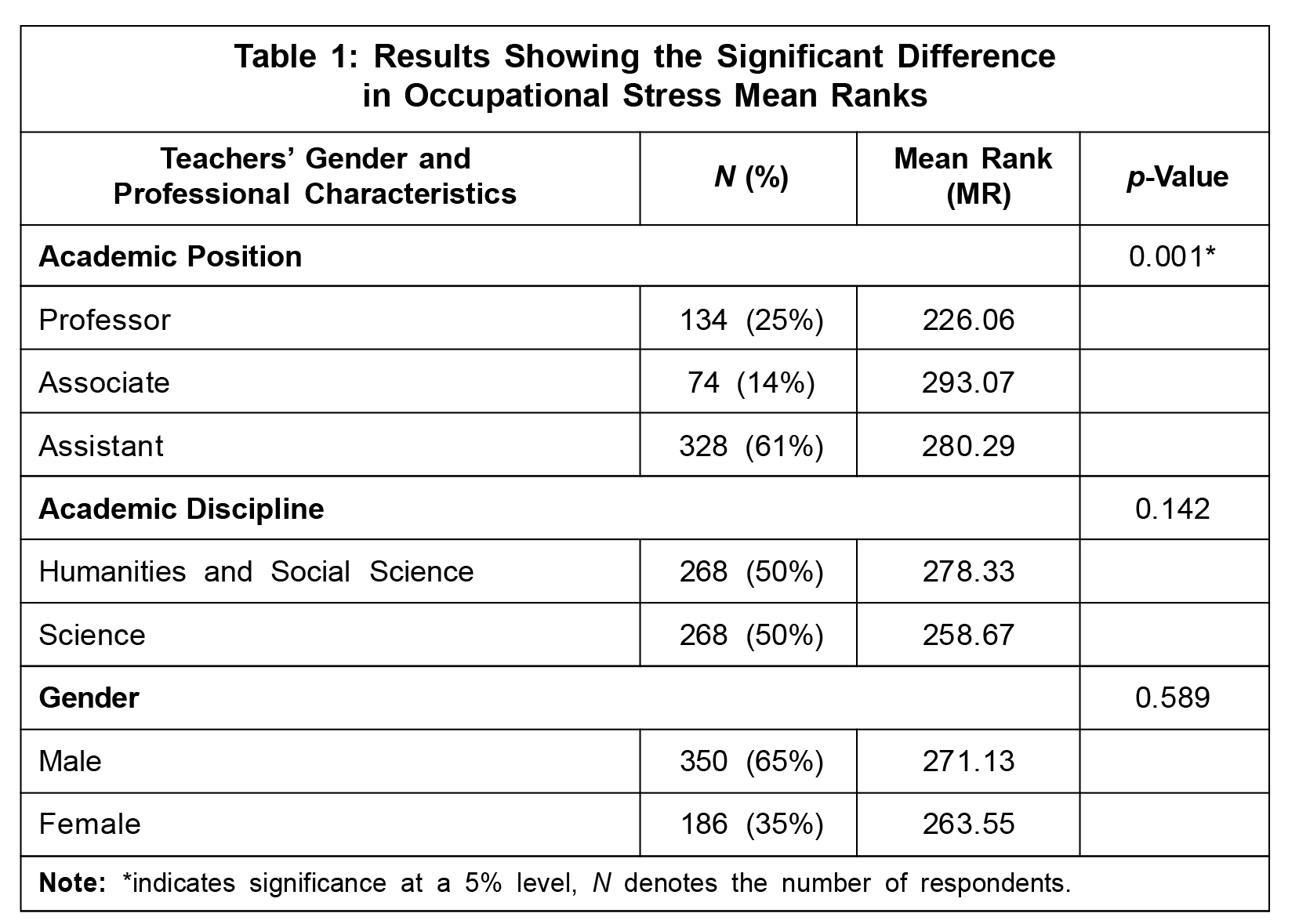

As shown in Table 1, the sample constitutes male (65%) and female (35%) teachers. A majority of the respondents are assistant professors (61%), followed by professors (25%) and associate professors (14%). Academic discipline is categorized into Science and Humanities Social Science (HSS), with an equal number of respondents in each of the two disciplines (50% each).

Occupational Stress Level Across Gender and Professional Characteristics of Teachers

Table 1 depicts how occupational stress level varies across gender and professional characteristics of the teachers. The results show no significant difference in occupational stress level across gender and academic discipline, as the p-values observed for both the variables are higher than 0.05. A few other researchers have supported this result that both males and females experience quite a similar level of occupational stress in their respective professions (Shkembi et al., 2015; Prasad et al., 2016; Ismail and Noor, 2016; Meng and Wang, 2018; Faraji et al., 2019; Devi and Lahkar, 2021; and Han

et al., 2021).

Because both male and female teachers are subjected to the same assessment standards and regulations in the higher education system, their levels of occupational stress are comparable (Meng and Wang, 2018). Moreover, the growing engagement of females in the workforce and new educational arenas has resulted in a convergence in the perception of both males and females (Eagly and Wood, 2012), resulting in considerably more similarity in the appraisal of their workplace stressors. Although there is no significant difference in occupational stress levels between the genders in this study, the mean ranks reveal that male teachers (MR = 271.13) are more stressed than female teachers (MR = 263.55). These results contradict the majority of previous research findings, which indicate that females are more stressed than males (Akbar and Akhter, 2011; Herrero et al., 2012; Marinaccio et al., 2013; Kataoka et al., 2014; Berebitsky and Ellis, 2018; and Kachi et al., 2020; and Liu, 2020). There is a notion that females' position in the North Eastern Region (NER) of India is comparatively better than the national average as they enjoy greater freedom and gender equality (Census, 2011). This cultural advantage of females in the states of North East India enables them to experience a lesser degree of gender stereotype, thereby reducing the impact of stress on them at their workplace. Based on the evidence found from the analysis, we reject the first hypothesis, which asserts that female teachers perceive significantly more occupational stress than male teachers.

Similar to previous research findings, the current study indicated no significant differences in occupational stress levels of the teachers in the two academic disciplines (Thorsen, 1996; Winefield and Jarrett, 2001; Winefield et al., 2002; and Meng and Wang, 2018). One probable explanation is that all academic areas are affected in the same way by common problems that most universities encounter, such as excessive workload, unpleasant working conditions, and a lack of resources (Kang and Sidhu, 2015), leading to a comparable level of occupational stress across all disciplines. However, other studies have found a substantial variation in the degree of occupational stress experienced by teachers in different academic disciplines (Lindholm and Szelenyi, 2008; and Berebitsky and Ellis, 2018). The comparison of mean ranks in the current study further shows that the teachers in humanities and social science (MR = 278.33) are more stressed as compared to the science teachers (MR = 258.67), which is consistent with the results found by Thorsen (1996), and Berebitsky and Ellis (2018). Teachers in humanities experience more stress from manuscript preparation for publication than teachers in natural science, engineering, and health disciplines (Perlberg and Keinan, 1986). Another study reported time stress, institutional duties, and teaching as more stressful for humanities teachers than those in maths and science (Thorsen, 1996). Moreover, a lack of financial and personnel support in conducting research is a major stressor for teachers in the field of humanities than in the science discipline (Berebitsky and Ellis, 2018). Therefore, we accept the second hypothesis, which states that the occupational stress level of university teachers remains independent of their academic discipline.

Furthermore, a significant difference (p < 0.05) is observed in the occupational stress level of teachers across the academic position, which is in line with most of the previous studies (Akbar and Akhter, 2011; Kataoka et al., 2014; Meng and Wang, 2018; Li and Kou, 2018; and Han et al., 2021). Out of the three categories of academic position, the associate professors (MR = 293.07) scored the highest mean rank on occupational stress, followed by assistant professors (MR = 280.29) and professors (MR = 226.06). This finding aligns with a few previous studies conducted in the university setting (Winefield and Jarrett, 2001; Jacob and Winslow, 2004; Barkhuizen and Rothman, 2008; Sun et al., 2011; and Li and Kou, 2018). Generally, teachers at higher ranks, such as professors, are considered more satisfied and less stressed due to their promotion, higher salary levels (Oshagbemi, 2003; Li and Kou, 2018; and Meng and Wang, 2018), and lesser workload (Jacob and Winslow, 2004). On the other hand, being new to the profession, the assistant professors view their higher workload set by the institutions as a temporary adjustment required to earn tenure (Jacob and Winslow, 2004), causing lesser occupational stress.

The associate professors mainly belong to the age group of 36 to 45 years with 6 to 15 years of work experience. During this phase of life, the teachers are confronted with various pressures ranging from scientific research (Meng and Wang, 2018), to career advancement and changes in financial and family conditions (Li and Kou, 2018), which can add to their psychological load. Based on this empirical evidence, we partially reject the second hypothesis of the study, which states that teachers working in lower academic positions perceive a higher level of occupational stress than those in higher academic positions. The current study finds the teachers in the middle position, i.e., associate professors, to be more stressed than those in the lower and top positions.

Sources of Occupational Stress Across Gender and Professional Characteristics of the Teachers

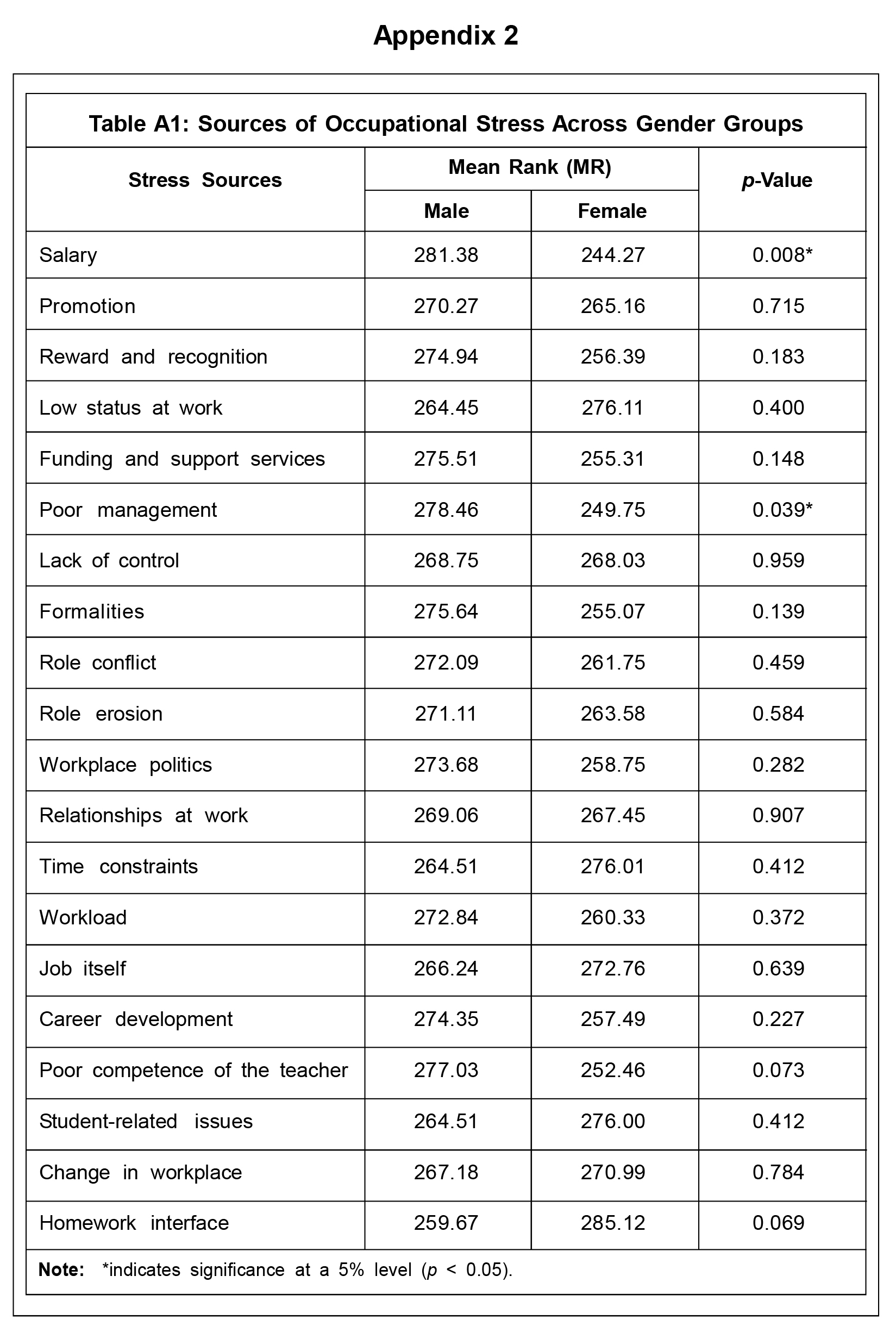

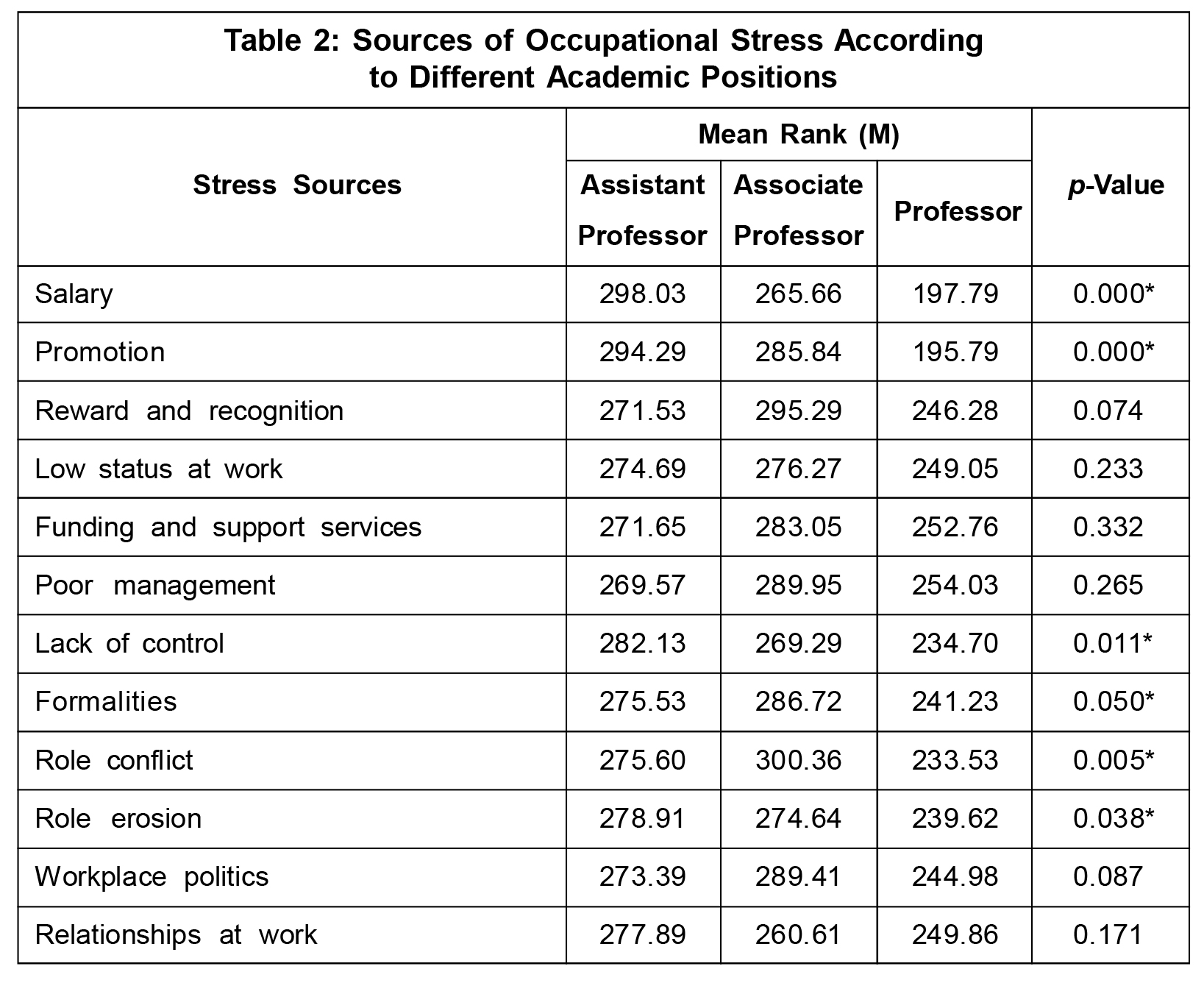

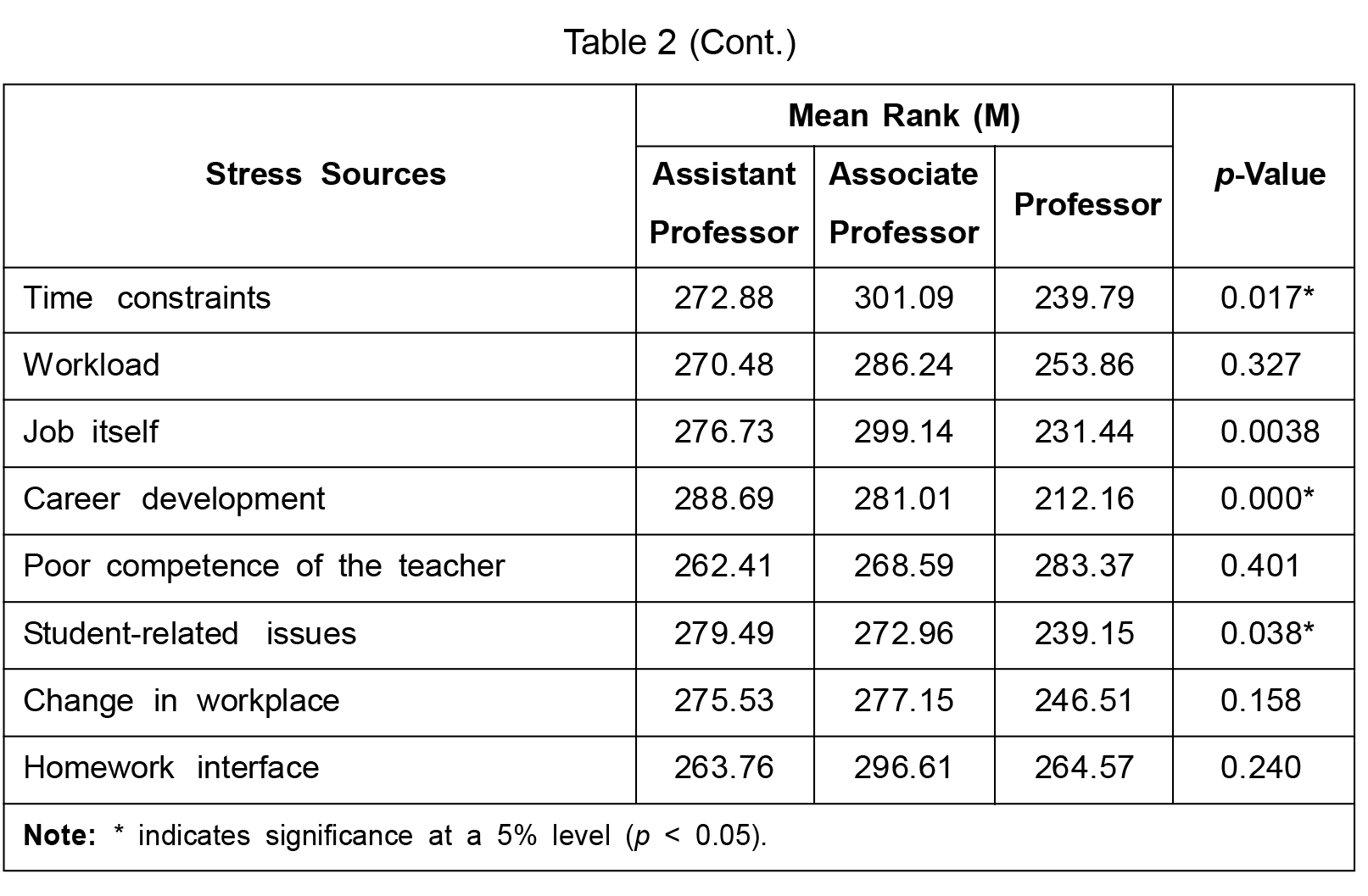

As shown in Table 2, mean ranks are determined to compare the sources of occupational stress and examine their significant differences (p < 0.05) across each of the three academic positions: assistant professor, associate professor, and professor. Similarly, comparisons of mean ranks across gender and academic discipline are presented in Appendices 2 and 3 (since no significant differences in occupational stress level are found across these two characteristics). The results revealed a significant difference (p < 0.05) in 10 out of 20 stress sources according to the three academic positions, including salary, promotion, lack of control, formalities, role conflict, role erosion, time constraints, job itself, career development, and student-related issues. On comparing the mean ranks of these stress sources, it is found that assistant professors have scored the highest score for the stressors, namely, salary (MR = 298.03), promotion (MR = 294.29), career development (MR = 288.69), lack of control (MR = 282.13), student-related issues (MR = 279.49) and role erosion (MR = 278.91) as compared to associate professors and professors. Since income level and academic position are closely related to one's degree of stress, teachers with lower income levels showed greater stress levels and vice versa (Li and Kou, 2018). In the Indian context, Kumar and Deo (2011) observed that unnecessary delay in promotion, red-tapism, and shifting of workload to junior members caused more stress in junior teachers than the senior ones. Likewise, Pestonjee and Azeem (2001) reported role erosion and resource inadequacy as the major stressors among the lecturers in one of the Indian universities. Moreover, the present study showed time constraints (MR = 301.09), role conflict (MR = 300.36), job itself (MR=299.14) and formalities (MR = 286.72) as the most stressful sources for associate professors relative to assistant professors and professors. Two other studies found higher job demands (Barkhuizen and Rothman, 2008) and scientific research (Meng and Wang, 2018) causing more stress in the associate professors. None of the nine stressors studied in this study caused more stress in professors compared to their counterparts, which might be attributed to a stronger sense of security, authority, and autonomy in the higher position (Sliskovic and Sersic, 2011).

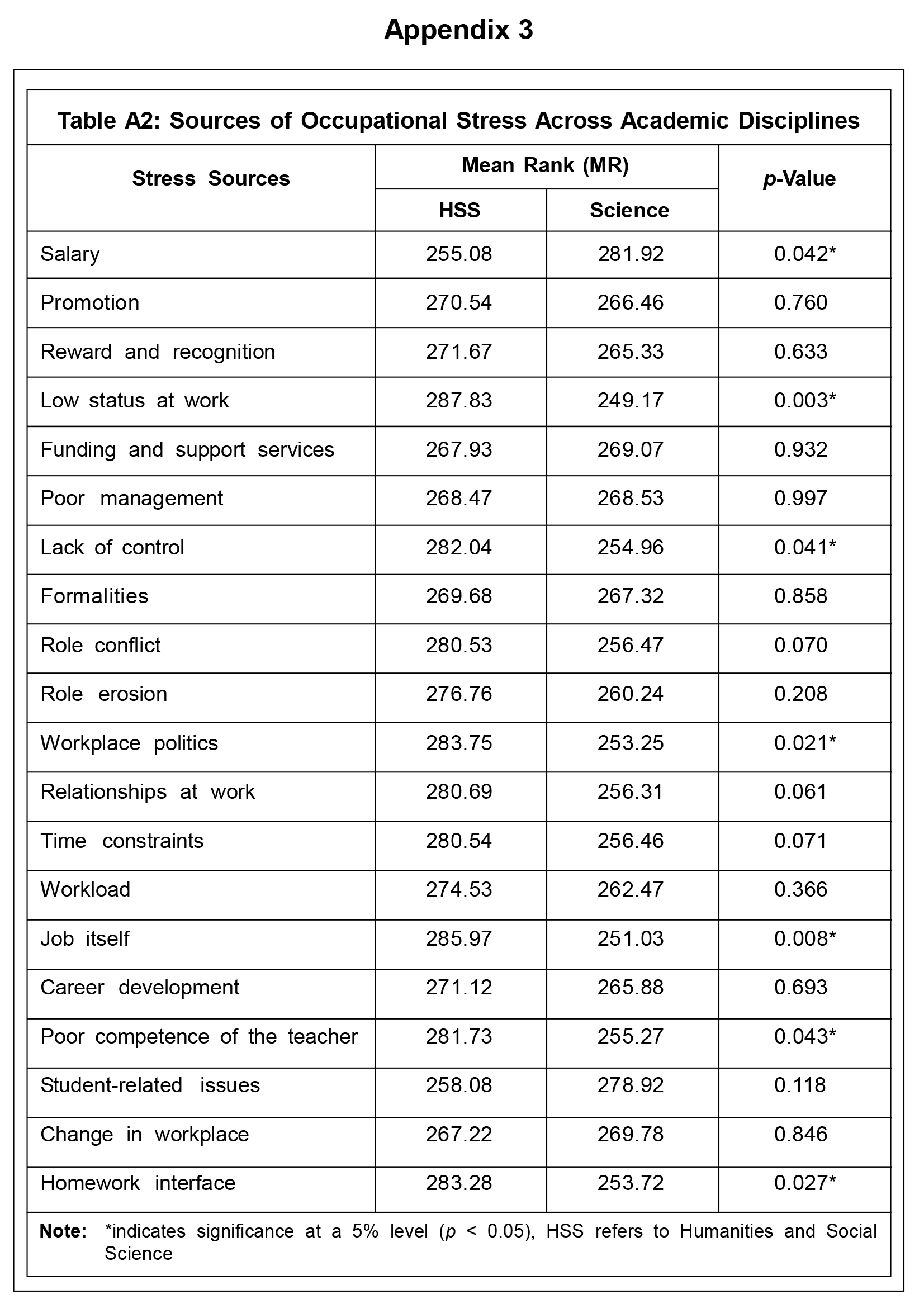

Even though the differences in the stress level across gender and academic discipline are minor, significant differences are observed for a few occupational stress sources. The results showed a significant difference (p < 0.05) across gender for only two stressors, namely, salary (MR = 281.38) and poor management (MR = 278.46), which are more stressful for male teachers as compared to female teachers (Appendix 2). This finding agrees with the results of McDonough and Walters (2001) and Matud (2004), where males reported occupational stress related to work and financial matters more frequently than females. Males are more likely to assume responsibility for the entire family while pursuing their careers, making their jobs more difficult. In comparison, female employees are more likely to receive assistance and social support from others causing less occupational stress (Jiang et al., 2018). Regarding academic discipline, a significant difference

(p < 0.05) is observed for 7 out of 20 stress sources, including salary, low status at work, lack of control, workplace politics, the job itself, poor competence of the teacher, and homework interface. Teachers in the discipline of humanities and social sciences scored the highest mean ranks for most of the stress sources such as low status at work

(MR = 287.83), the job itself (MR = 285.97), workplace politics (MR = 283.75), homework interface (MR = 283.28), lack of control (MR = 282.04) and poor competence of the teacher (MR = 281.73). In comparison, salary (MR = 281.92) is the only stressor causing significantly more stress in teachers from the science discipline (Appendix 3). Other researchers have also reported that humanities and social sciences teachers experience more occupational stress than science teachers (Perlberg and Keinan, 1986; Thorsen, 1996; and Berebitsky and Ellis, 2018).

Conclusion

The main purpose of the current study is to examine the phenomenon of occupational stress according to gender and professional characteristics, including academic position and discipline of the university teachers in Assam. This study also attempts to identify the sources of occupational stress across the selected characteristics of teachers. The results show a significant difference in the level of occupational stress experienced by teachers in different academic positions, but not in terms of gender or academic discipline. The teachers in the academic position of associate professor experienced the highest stress level, followed by the assistant professors and the professors. Although no significant differences were observed, the male teachers experienced higher occupational stress than female teachers. Similarly, the occupational stress level of teachers in the humanities and social sciences is higher than those in the science stream. Total 15 of the 20 occupational stressors examined in this study, including salary, promotion, lack of control, formalities, role conflict, role erosion, time constraints, career development, student-related issues, poor management, low status at work, workplace politics, the job itself, poor competence of the teacher and homework interface, showed significant differences across the academic position, academic discipline, and gender of the teachers. Assistant professors perceived salary, promotion, and career development as their top concerns, whereas associate professors indicated stress from time constraints, role conflict, job itself and formalities as the key stressors. In contrast, professors experienced the least stress from the significant stress sources compared to their counterparts in the academic positions of associate and assistant professor.

Implications: The study findings could be valuable for various groups, including educational policymakers, university administrators, statutory authorities, instructors, and researchers. The differences in the occupational stress level and identified stress sources across teachers' gender, academic position, and academic discipline may enable higher authorities to take appropriate interventions to address these issues in each group of teachers. Unnecessary formalities, such as long procedures for approval of teacher initiatives, should be eliminated from everyday operations to make teacher advancement and career growth easier. As a result, this would reduce role conflict, time constraints, and the homework interface issues of the teachers caused by an excessive workload. Furthermore, teachers' perspectives should be considered while making changes to the functioning of the university system to increase their autonomy, improve their status at work and perceptions towards management, and decrease workplace politics and role erosion. Student-related issues should be addressed by maintaining quality standards in the admission process and expanding the number of teachers in each department for adequate representation. At an individual level, coping strategies such as meditation, workouts, recreational activities, positivism, social interactions, etc., could be adopted to minimize the detrimental impact of occupational stress on the wellbeing of the teachers.

Limitations and Future Scope: The current study has a few drawbacks, such as using a self-rated questionnaire, which may result in social desirability due to inaccurate marking of the statements. To overcome this issue, a mixed-method approach could be used to obtain more relevant responses, including a questionnaire and a structured interview. The limited sample size and geographical area selected for the current study restrict the generalizability of the findings. Moreover, this study is limited to variables such as gender, academic position, and discipline of university teachers. Therefore, future investigations may include other teacher-related characteristics such as family-related factors, age, administrative position, number of publications, working hours, etc., and examine the differences in occupational stress levels across their interactions. An employee's workplace wellbeing is largely determined by the dynamics of the work environment and the conditions that influence it. Therefore, a holistic evaluation of teachers' workplace environment is critical to having a stress-free atmosphere, which could provide a promising future for the upcoming generation.

References

- Akbar A and Akhter W (2011), "Faculty Stress at Higher Education: A Study on the Business Schools of Pakistan", World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology, Vol. 5, No. 1, pp. 93-97.

- Altbach P G and Boyer E L (1996), The International Academic Profession, Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, Princeton, NJ.

- Antoniou A S, Polychroni F and Vlachakis A N (2006), "Gender and Age Differences in Occupational Stress and Professional Burnout Between Primary and Highschool Teachers in Greece", Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 21, No. 7, pp. 682-690.

- Annandale E and Hunt K (1990), "Masculinity, Femininity and Sex: An Exploration of their Relative Contribution to Explaining Gender Differences in Health", Sociology of Health and Illness, Vol. 12, No. 1, pp. 24-46.

- Bain O and Cummings W (2000), "Academe's Glass Ceiling: Societal, Professional-Organizational, and Institutional Barriers to the Career Advancement of Academic Female", Comparative Education Review, Vol. 44, No. 4, pp. 493-514.

- Barkhuizen N and Rothmann S (2008), "Occupational Stress of Academic Staff in South African Higher Education Institutions", South African Journal of Psychology, Vol. 38, No. 2, pp. 321-336.

- Barnes L L, Agago M O and Coombs W T (1998), "Effects of Job-Related Stress on Faculty Intention to Leave Academia", Research in Higher Education, Vol. 39, No. 4, pp. 457-469.

- Beach B (1989), Integrating Work and Family Life: The Home-Working Family, SUNY Press.

- Berebitsky D and Ellis M K (2018), "Influences on Gender and Professional Stress on Higher Education Faculty", Journal of the Professoriate, Vol. 9, No. 2, pp. 88-110.

- Biglan A (1973), "The Characteristics of Subject Matter in Different Academic Area", Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 57, No. 3, pp. 195-203.

- Bird S R and Rhoton L A (2021), "Seeing isn't Always Believing: Gender, Academic STEM, and Female Scientists' Perceptions of Career Opportunities", Gender & Society, Vol. 35, No. 3, pp. 422-448.

- Blix A G, Cruise R J, Mitchell B M and Blix G G (1994), "Occupational Stress Among University Teachers", Educational Research, Vol. 36, No. 2, pp. 157-169.

- Bromberger J T and Matthews K A (1996), "A Feminine Model of Vulnerability to Depressive Symptoms: A Longitudinal Investigation of Middle-Aged Female", Journal of Genderity and Social Psychology, Vol. 70, No. 3, pp. 591.

- Brown R D, Bond S, Gerndt J et al. (1986), "Stress on Campus: An Interactional Perspective", Research in Higher Education, Vol. 24, No. 1, pp. 97-112.

- Census of India (2011), "Provisional Population Totals", Registrar General of India, New Delhi.

- Cotter D A, Hermsen J M and Vanneman R (2001), "Female's Work and Working Female: The Demand for Female Labor", Gender and Society, Vol. 15, No. 3, pp. 429-452.

- De Paula A V and Boas A A V (2017), "Well-Being and Quality of Working Life of University Professors in Brazil", Chapter 10 in Quality of Life and Quality of Working Life, Rijeka, InTechpp, 187-210.

- Devi P and Lahkar N (2021), "Occupational Stress and Job Performance Among University Library Professionals of North-East India", Evidence-Based Library and Information Practice, Vol. 16, No. 2, pp. 2-21.

- Doberneck D M and Schweitzer J H (2017), "Disciplinary Variations in Publicly Engaged Scholarship: An Analysis Using the Biglan Classification of Academic Disciplines", Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement, Vol. 21, No. 1, pp. 78-103.

- Eagly A H (1987), Sex Differences in Social Behavior: A Social Role Interpretation, Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ.

- Eagly A H and Wood W (1991), "Explaining Sex Differences in Social Behavior: A Meta-Analytic Perspective", Genderity and Social Psychology Bulletin, Vol. 17, No. 3, pp. 306-315.

- Eagly A H and Karau S J (2002), "Role Congruity Theory of Prejudice Toward Female Leaders", Psychological Review, Vol. 109, No. 3, pp. 573-598.

- Eagly A H and Wood W (2012), "Social Role Theory", in P Van Lange, A Kruglanski and E T Higgins (Eds.), Handbook of Theories in Social Psychology, pp. 458-476, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA.

- Ely R J and Meyerson D E (2000), "Theories of Gender in Organizations: A New Approach to Organizational Analysis and Change", Research in Organizational Behavior, Vol. 22, No. 1, pp. 103-151.

- Faraji A Karimi M, Azizi S M, Janatolmakan M and Khatony A (2019), "Occupational Stress and its Related Gender Factors Among Iranian CCU Nurses: A Cross-Sectional Study", BMC Research Notes, Vol. 12, No. 1, pp. 1-5.

- Gillespie N A, Walsh M H W A, Winefield A H et al. (2001), "Occupational Stress in Universities: Staff Perceptions of the Causes, Consequences, and Moderators of Stress", Work and Stress, Vol. 15, No. 1, pp. 53-72.

- Gmelch W H, Wilke P K and Lovrich N P (1986), "Dimensions of Stress Among University Faculty: Factor-Analytic Results from a National Study", Research in Higher Education, Vol. 24, No. 3, pp. 266-286.

- Gotz S, Hoven H, Muller A et al. (2018), "Age Differences in the Association Between Stressful Work and Sickness Absence Among Full-Time Employed Workers: Evidence from the German Socio-Economic Panel", International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, Vol. 91, No. 4, pp. 479-496.

- Green E and Cassell C (1996), "Female Managers, Gendered Cultural Processes and Organizational Change, Gender", Work and Organization, Vol. 3, No. 3, pp. 168-178.

- Han J, Perron B E, Yin H and Liu Y (2021), "Faculty Stressors and their Relations to Teacher Efficacy, Engagement and Teaching Satisfaction", Higher Education Research & Development, Vol. 40, No. 2, pp. 247-262.

- He X X, Li Z Y, Shi J et al. (2000), "A Comparative Study of Stress Among University Faculty in China and Japan", Higher Education, Vol. 39, No. 3, pp. 253-277.

- Herrero S G, Saldana M a M, Rodriguez J G and Ritzel D O (2012), "Influence of Task Demands on Occupational Stress: Gender Differences", Journal of Safety Research, Vol. 43, Nos. 5-6, pp. 365-374.

- Hofstede G (1986), "Cultural Differences in Teaching and Learning", International Journal of Intercultural Relations, Vol. 10, No. 3, pp. 301-320.

- Hofstede G, Hofstede G J and Minkov M (2005), Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind, McGraw-Hill, New York.

- Hogan J M, Carlson J G and Dua J (2002), "Stressors and Stress Reactions Among University Personnel", International Journal of Stress Management, Vol. 9, No. 4, pp. 289-310.

- Hoyos C A and Serna C A (2021), "Rewards and Faculty Turnover: An Individual Differences Approach", Cogent Education, Vol. 8, No. 1, pp. 1863170.

- International Labor Organization (ILO) (2016), Workplace Stress: A Collective Challenge, Geneva.

- Ismail N H and Noor A (2016), "Occupational Stress and its Associated Factors Among Academicians in a Research University, Malaysia", Malaysian Journal of Public Health Medicine, Vol. 16, No. 1, pp. 81-91.

- Jacobs J A and Winslow S E (2004), "Overworked Faculty: Job Stresses and Family Demands", The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 596, No. 1, pp. 104-129.

- Jiang T, Tao N, Shi L et al. (2018), "Associations Between Occupational Stress and Gender Characteristics in Petroleum Workers in the Xinjiang Arid Desert", Medicine, Vol. 97, No. 31, pp. 1-6.

- Johnson S, Cooper C, Cartwright S et al. (2005), "The Experience of Workrelated Stress Across Occupations", Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 20, No. 2, pp. 178-187.

- Kachi Y, Inoue A, Eguchi H et al. (2020), "Occupational Stress and the Risk of Turnover: A Large Prospective Cohort Study of Employees in Japan", BMC Public Health, Vol. 20, No. 1, pp. 174.

- Kang L S and Sidhu H (2015), "Identification of Stressors at Work: A Study of University Teachers in India", Global Business Review, Vol. 16, No. 2, pp. 303-320.

- Kataoka M, Ozawa K, Tomotake M et al. (2014), "Occupational Stress and its Related Factors Among University Teachers in Japan", Health, Vol. 6, No. 5, pp. 299-305.

- Kazmi R, Amjad S and Khan D (2008), "Occupational Stress and Its Effect on Job Performance. A Case Study of Medical House Officers of District Abbottabad", J. Ayub. Med. Coll. Abbottabad, Vol. 20, No. 3, pp. 135-139.

- Kim S Y, Shin D W, Oh K S et al. (2018), "Gender Differences of Occupational Stress Associated with Suicidal Ideation Among South Korean Employees: The Kangbuk Samsung Health Study", Psychiatry Investigation, Vol. 15, No. 2, pp. 156.

- Kinman G and Jones F (2003), "Running Up the Down Escalator: Stressors and Strains in UK Academics", Quality in Higher Education, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 21-38.

- Kinman G (2016), "Effort-Reward Imbalance and Over Commitment in UK Academics: Implications for Mental Health, Satisfaction and Retention", Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, Vol. 38, No. 5, pp. 504-518.

- Kumar D and Deo J M (2011), "Stress and Work-Life of College Teachers", Journal of the Indian Academy of Applied Psychology, Vol. 37, No. 1, pp. 78-85.

- Lazarus R S (1966), Psychological Stress and the Coping Process, McGraw-Hill, New York.

- Lease S H (1999), "Occupational Role Stressors, Coping, Support, and Hardiness as Predictors of Strain in Academic Faculty: An Emphasis on New and Female Faculty", Research in Higher Education, Vol. 40, No. 3, pp. 285-307.

- Li W and Kou C (2018), "Prevalence and Correlates of Psychological Stress Among Teachers at a National Key Comprehensive University in China", International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health, Vol. 24, Nos. 1-2, pp. 7-16.

- Liu X (2020), "Research on the Professional Stress of University Teachers-Take the Universities in Anyang City, Henan Province as an Example", Creative Education, Vol. 11, No. 9, pp. 1679-1689.

- Lindholm J A and Szelenyi K (2008), "Faculty Time Stress: Correlates within and Across Academic Disciplines", Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, Vol. 17, Nos. 1-2, pp. 19-40.

- Marinaccio A, Ferrante P, Corfiati M et al. (2013), "The Relevance of Socio-Gender and Occupational Variables for the Assessment of Work-Related Stress Risk", BMC Public Health, Vol. 13, No. 1, pp. 1-9.

- Marcoux G, Guihur I and Leclerc A (2021), "Co-Operative Difference and Organizational Commitment: The Filter of Socio-Gender Variables", The International Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 32, No. 4, pp. 822-845.

- Matud M P (2004), "Gender Differences in Stress and Coping Styles", Genderity and Individual Differences, Vol. 37, No. 7, pp. 1401-1415.

- McDonough P and Walters V (2001), "Gender and Health: Reassessing Patterns and Explanations", Social Science and Medicine, Vol. 52, No. 4, pp. 547-559.

- Meng Q and Wang G (2018), "A Research on Sources of University Faculty Occupational Stress: A Chinese Case Study", Psychology Research and Behavior Management, Vol. 11, No. 1, pp. 597-605.

- Mittal G and Purohit H (2012), "Factors Affecting the Level of Work Stress of Employees of Different Genderity Traits in Education Sector", Radix International Journal of Economics and Business Management, Vol. 1, No. 9, pp. 1-16.

- Neumann Y and Finaly-Neumann E (1990), "The Support-Stress Paradigm and Faculty Research Publication", The Journal of Higher Education, Vol. 61, No. 5, pp. 565-580.

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) (1999), "Stress at Work Centers for Disease Control and Prevention", U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Publication No. 99-101, 26.

- Oshagbemi T (2003), "Gender Correlates of Job Satisfaction: Empirical Evidence from UK Universities", International Journal of Social Economics, Vol. 30. No. 12, pp. 1210-1232.

- Perlberg A and Keinan G (1986), "Sources of Stress in Academe: The Israeli Case", Higher Education, Vol. 15, No. 1, pp. 73-88.

- Pestonjee D M and Azeem S M (2001), "A Study of Organisational Role Stress in Relation to Job Burnout Among University Teacher", Working paper No. 2001-04-02.

- Prasad K D V, Vaidya R and Kumar V A (2016), "Teacher's Performance as a Function of Occupational Stress and Coping with Reference to CBSE Affiliated School Teachers in and around Hyderabad: A Multinomial Regression Approach", Psychology, Vol. 7, No. 13, pp. 1700-1718.

- Reddy G L and Poornima R (2012), "Occupational Stress and Professional Burnout of University Teachers in South India", International Journal of Educational Planning and Administration, Vol. 2, No. 2, pp. 109-124.

- Robertson A and Tracy C S (1998), "Health and Productivity of Older Workers", Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment and Health, Vol. 24, No. 2, pp. 85-97.

- Scheibe S, Spieler I and Kuba K (2016), "An Older-Age Advantage? Emotion Regulation and Emotional Experience After a Day of Work", Work, Aging and Retirement, Vol. 2, No. 3, pp. 307-320.

- Selye H (1956), The Stress of Life, McGraw-Hill, New York.

- Shkembi F, Melonashi E and Fanaj N (2015), "Workplace Stress Among Teachers in Kosovo", SAGE Open, Vol. 5, No. 4, pp. 1-8.

- Shin J C and Jung J (2014), "Academics Job Satisfaction and Job Stress Across Countries in the Changing Academic Environments", Higher Education, Vol. 67, No. 5, pp. 603-620.

- Sliskovia A and Maslaa Sersia D (2011), "Work Stress Among University Teachers: Gender and Position Differences", Arh Hig Rada Toksikol, Vol. 62, No. 4, pp. 299-306.

- Smith E, Anderson J L and Lovrich N P (1995), "The Multiple Sources of Workplace Stress Among Land-Grant University Faculty", Research in Higher Education, Vol. 36, No. 3, pp. 261-282.

- Srivastava A K and Singh A P (1981), "Construction and Standardization of an Occupational Stress Index: A Pilot Study", Indian Journal of Clinical Psychology, Vol. 8, No. 2, pp. 133-136.

- Sun W, Wu H and Wang L (2011), "Occupational Stress and its Related Factors Among University Teachers in China", Journal of Occupational Health, Vol. 53,No. 1, pp. 280-286.

- Taberner A M (2018), "The Marketisation of the English Higher Education Sector and its Impact on Academic Staff and the Nature of their Work", International Journal of Organizational Analysis, Vol. 26, No. 1, pp. 129-152.

- Thorsen E J (1996), "Stress in Academe: What Bothers Professors?", Higher Education, Vol. 31, No. 4, pp. 471-489.

- Tilak J B (2021), Teachers and Teacher Education in India: Issues, Trends and Challenges, Trends and Challenges, July 7, 2021.

- Tiwari M and Pant P (2017), "Changing Roles of Teaching Professionals: Issues and Challenges", International Journal of Current Research, Vol. 9, No. 6, pp. 52859-52862.

- Vakola M and Nikolaou I (2005), "Attitudes Towards Organizational Change", Employee Relations, Vol. 27, No. 2, pp. 160-174.

- Winefield A H and Jarrett R (2001), "Occupational Stress in University Staff", International Journal of Stress Management, Vol. 8, No. 4, pp. 285-298.

- Winefield A H, Gillespie N, Stough C et al. (2002), "Occupational Stress in Australian Universities: A National Survey", Doctoral Dissertation, National Tertiary Education Union).

- Zaheer A, Islam J U and Darakhshan N (2016), "Occupational Stress and Work-Life Balance: A Study of Female Faculties of Central Universities in Delhi, India", Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 4, No. 1, pp. 1-5.