October '22

The IUP Journal of Organizational Behavior

Archives

Does the Organization Have an Impact on the Happiness and Life Satisfaction of Agricultural Scientists in India?

P Ramesh

Principal Scientist and Professor, Human Resource Management (HRM) Divisions, ICAR-National Academy of Agricultural Research Management (NAARM), Rajendranagar, Hyderabad, Telangana, India; and is the corresponding author. E-mail: pramesh.icar@gmail.com

B S Yashavanth

Scientist, Information and Communication Management (ICM) Division, ICAR-NAARM, Rajendranagar, Hyderabad, Telangana, India, E-mail: yashavanthbs@gmail.com

V S Rao

Principal Scientist and Head, HRM Division, ICAR-NAARM, Rajendranagar, Hyderabad, Telangana, India, E-mail: rvs@naarm.org.in

Happiness at workplace is important for both individuals and organizations, as it is known to increase and sustain employee productivity. The present study assesses the personality and wellbeing attributes of agricultural scientists to find out any differences in these attributes between the scientists working in two different organizations viz., Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) and State Agricultural Universities (SAUs). The findings revealed that the agricultural scientists, irrespective of the organization in which they are working, have similar personality traits and equal scores on the happiness index. However, SAU scientists are found to have higher scores on life satisfaction and lower scores on Psychological Wellbeing (PWB) compared to ICAR scientists. Even though at the beginning of their career, scientists from SAU were reported to have higher wellbeing, in the long run, ICAR scientists were found to sustain their levels of happiness and PWB.

Introduction

Agricultural scientists are continually looking for ways to improve livestock, crop yields, and food quality while also conserving the environment (CAERT, 2006). The National Agricultural Research and Education System (NARES) in India primarily comprises a network of 101 research institutions working directly under the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) and 71 agricultural universities, which is one of the largest national agricultural research systems in the world. There are about 40,000 professionally trained scientific personnel employed in NARES to look after research, education, and extension activities. These scientific personnel specialized in about 90 different disciplines of agricultural sciences, covering field crops, horticulture, animal sciences, fisheries, engineering, and social sciences (ICAR, 2021).

Scientists play a critical role in informing the public about science's content and procedures. They must take the time to relate scientific knowledge to society in such a way that members of the public can make an informed judgment about the relevance of research while fulfilling their tasks. It is envisaged that society will have sufficient awareness of their behavior in respect to scientists' activity (Sato, 2016).

Literature Review

As compared to other pieces of information about them, such as historical narratives and philosophical foundations, the scientists' psychological qualities remain poorly known (Feist and Gorman, 1998; and Feist, 2006). Psychological research on scientists is essential since it can reveal their true traits and could have ramifications for other scientific literatures (Shadish et al., 1989). Understanding the psychological characteristics of scientists is helpful to assess their career satisfaction (Lounsbury et al., 2012) and wellbeing (Sato, 2016), and may also prove useful in improving education and recruitment programs (Feist and Gorman, 1998; and Ramesh and Rao, 2020).

Scientists are thought to have strong feelings of happiness because of their occupation. This is in line with the many anecdotal reports that indicate scientists derive greater happiness through their work (Wolpert and Richards, 1997). Furthermore, studies have shown that scientists are less likely to suffer from mental illnesses than those who are not scientists (Ludwig, 1995; and Rawlings and Locarnini, 2008). However, no detailed study to date has measured scientists' Subjective Wellbeing (SWB). SWB focuses on the hedonic component of wellbeing, which is a pursuit of happiness and pleasant life at the individual level. It includes global assessments of affect and life quality (Diener, 2000). The Psychological Wellbeing (PWB) perspective stresses the value of 'eudaemonic' wellbeing, characterized by fulfillment of human potential and meaningful life, growing and developing as a person, and establishing quality ties with others (Ryff, 1989; Ryff and Keyes, 1995; and Ryff and Singer, 2008).

An employee can feel happy in the workplace when he or she can manage, fulfill, and produce results that they are satisfied with while at work (Pryce-Jones, 2010). Workplace happiness refers not only to individual intrinsic factors but also to individual extrinsic factors, such as the organizational environment, relationship with others (Carr, 2004) and other factors that are directly related to the tasks performed such as job satisfaction, autonomy, leadership, salary, reward and so on (Fisher, 2010). An organization's productivity will improve if its employees are happy. Productive people are happy people, while unhappy people are less likely to pay full attention to their tasks. Scholars believe that organizations that can maintain employee happiness at the workplace could increase and sustain productivity. Therefore, organizations should identify what factors affect employee happiness to effectively enhance worker happiness (Fisher, 2010; Wesarat et al., 2015; and Isa et al., 2019).

Leadership style is strongly linked to influencing employee satisfaction. Autocratic leaders will make employees feel the pressure and worry. This situation ultimately leads employees to feel less valued and more likely to resign or leave their current position. According to Bass (1995), transformative leadership traits such as intellectual stimulation, charismatic and individual-centered thinking can foster employee engagement, while employees who are willing to participate are those who are happy and satisfied with their work environment (Isa et al., 2019).

According to Gavin and Mason (2004), to achieve happiness in life, people need to work in an organization that can affect their level of happiness. Organizational support, such as the facilities provided, the role of management, and the influence of employees, are crucial for increasing the number of satisfied employees. Formal or informal interaction between employer and employee is strongly linked to employee satisfaction. Positive Organizational Behavior (POB) describes the positive constructs that exist in organizations that help in increasing employees' job satisfaction, engagement, job happiness, and prosocial behavior (Youssef and Luthans, 2007). In a recent study, it was found out that the personality traits as measured through Big-Five Inventory (BFI) are significantly correlated with happiness, life satisfaction and PWB attributes of scientists. A majority of scientists are found to be happier and well-satisfied by possessing personality traits required for a career in science, through which they get their happiness, life satisfaction and PWB (Ramesh et al., 2021).

A few studies have been conducted to investigate the wellbeing attributes of scientists in limited fields of science, but not on agricultural scientists to understand their subjective and psychological wellbeing associated with their profession. Hence, the present investigation was initiated.

Theoretical Framework

There has been a lot of debate in recent years about research productivity among scientists. The growing concern over research productivity of scientists in general and agricultural scientists in particular is more relevant in the context of ever-increasing demand to produce more food under adverse and changing environmental and climate conditions (Manjunath, 2011; and Paul et al., 2015 and 2017). The research findings revealed that the optimum scientific productivity of scientists can only be harnessed when personal and organizational factors work in harmony. The personal factors include scientists' personality traits and wellbeing attributes like their happiness, life satisfaction, and psychological wellbeing. Organizational factors include the overall work environment including leadership and management style. The broaden-and-build model (Fredrickson, 2001) provides the necessary framework to explain the possible interactive role of wellbeing in job satisfaction/job performance relation. Based on the happy/productive worker thesis, it is hypothesized that happy and satisfied scientists could be more productive in their profession.

There is a debate among the scientific community regarding the productivity and wellbeing of scientists in relation to their organizational environment, which includes the level of freedom, autonomy, funding for research and research infrastructure available, besides the leadership style of the organization. Attempts are made previously to study the differences in thinking abilities and leadership styles of scientists in NARES in India (Rao et al., 2017 and 2021). The basic presumption for this paper is to find out the organizational differences that may be positively managed for improving the wellbeing of scientists in ICAR and SAUs.

Objective

The present study was initiated with the following objectives:

- To assess the personality and wellbeing traits, viz., happiness, life satisfaction, and PWB of agricultural scientists;

- To find out any difference in these traits between the two organizations, viz., ICAR and State Agricultural Universities (SAUs); and

- To predict the happiness and life satisfaction level of agricultural scientists.

Data and Methodology

Sample

The study was conducted on the research scientists working in NARES in India. The participants include scientists working in various research institutes under ICAR which is a society under the administrative and financial control of the Department of Agricultural Research and Education (DARE) of the Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers' Welfare, Government of India and in SAUs which are under the administrative and financial control of concerned State governments. A majority of respondents in the study are participants in various capacity building programs being organized by the ICAR-National Academy of Agricultural Research Management (NAARM), Hyderabad, India, a training academy under ICAR during the period 2020-21. Besides, data was also collected from the scientists from both ICAR and SAUs online by Google Survey method during the same period. A total of 622 participants, including 261 from ICAR and 361 from SAUs, responded to the study. Among the participants, 68.2% were males and 31.8% were females. The age of the participants ranged from 23 to 66 years, with an average of 41.8 years and a standard deviation of 6.36. Their educational levels varied from postgraduation to PhD in their respective disciplines in agricultural and allied subjects. The participants have professional experience ranging from 1 to 36 years, with an average of 13.2 years and a standard deviation of 8.42.

Measurement Tools

Big-Five Inventory-10 (BFI-10)

The BFI is a scale that measures a person on the major five domains of personality, viz., extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness. The

BFI-10 comprises 10 items taken from the BFI-44, two items for each personality trait. Each item is estimated with the same Likert scale as for the BFI-44, giving a number of 2-10 for every domain total score (Rammstedt and John, 2007). It is a short-scale version of the well-established BFI and was developed to produce a questionnaire for research settings with extreme time constraints. Previous analysis has clearly shown that the

BFI-10 possesses psychological properties that are comparable in size and structure to those of the larger version of BFI (Gosling et al., 2003; and Balgiu, 2018).

Oxford Happiness Questionnaire (OHQ)

The OHQ is often used to estimate happiness attributes comprising 29 items (Hills and Argyle, 2002). Participants are asked to reply to every one of them on a six-point Likert-type scale (ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree), with higher scores indicating higher happiness. The OHQ has been shown to possess adequate test-retest dependableness (7-week duration = 0.78; 5-months duration = 0.67) and moderate to high internal consistency with a typical Cronbach between 0.64 and 0.87 (Argyle et al., 1989).

Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS)

The SWLS is a five-item tool for estimating existing global life satisfaction, that comprises a cognitive judgment of an individual's quality of life (Diener et al., 1985). Participants responded on a Likert scale from 1 - highly disagree, to 7 - highly agree. An example item is, "I am satisfied with my current life." Cronbach's values ranged from 0.89 to 0.91 across global regions (Pavot and Diener, 1993).

Psychological Wellbeing (PWB-18)

The scales of PWB consisted of six attributes of positive psychological functioning: "self-acceptance, positive relations with others, autonomy, environmental mastery, purpose in life, and personal growth" (Ryff, 1989). In this study, a shortened version of Ryff's PWB scale of 18-items with 3 items per subscale was used (Ryff and Keyes, 1995). Participants were asked to respond to a seven-point Likert scale giving a score of 1 for strongly agree to 7 for strongly disagree.

Procedure

A Google Form questionnaire was administered to the participants of the survey by highlighting the purpose and objectives of the survey, the confidentiality of data and the instructions to be followed by the participants while responding to the items in the survey. The data collected includes the socio-demographic details of the participants, followed by the statements in each of the test tools used in the survey. The survey questionnaire was administered to the participants online. The responses for the tests were scored and tabulated, and descriptive statistics indicators were calculated. The student's t-test was employed for organization-wise comparisons. Carl Pearson's correlation and regression analysis were carried out to check and quantify the association between different study variables. The analysis was carried out using statistical software R Version 4.1.0.

Results and Discussion

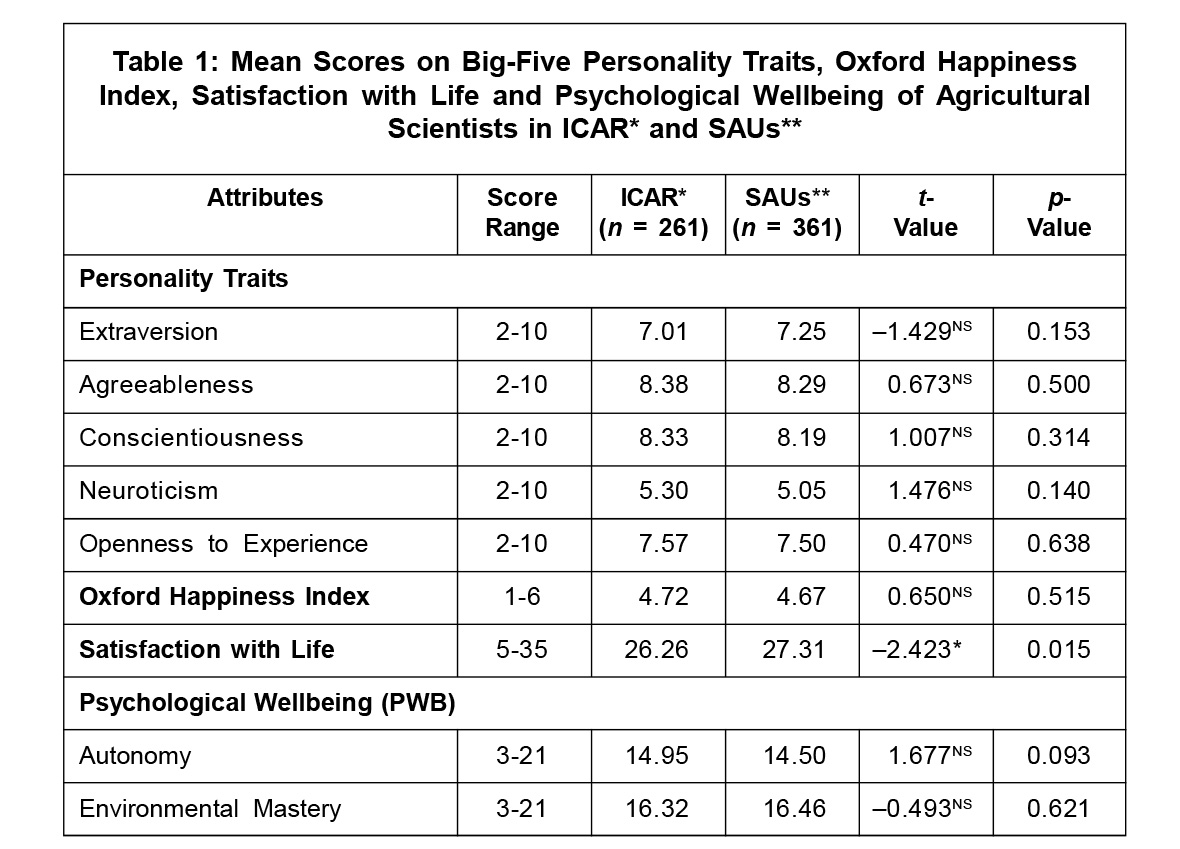

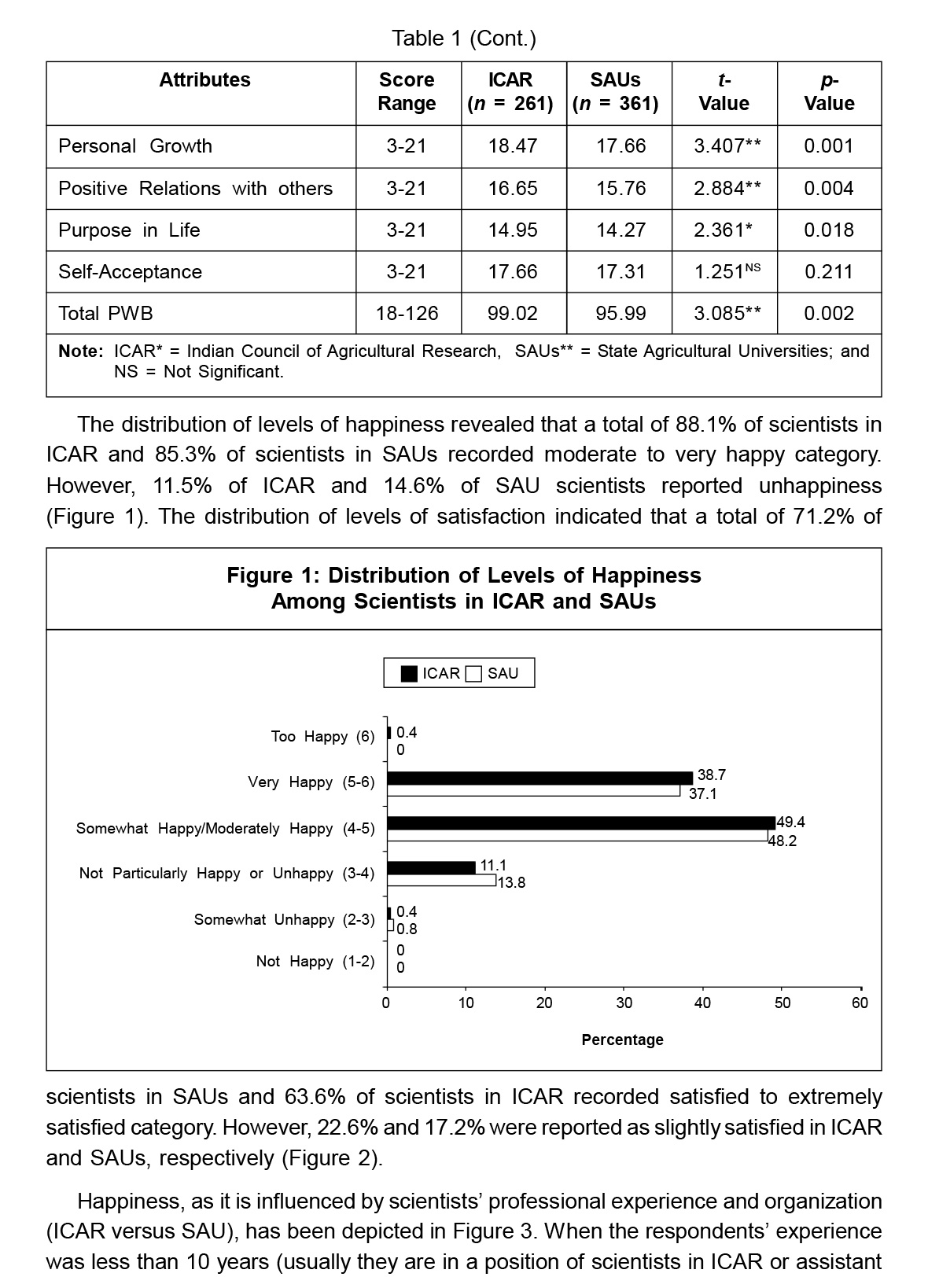

The mean scores on Big-Five personality traits and happiness index did not significantly differ between ICAR and SAU scientists (Table 1). However, scientists from SAUs recorded significantly higher scores on life satisfaction (27.31) compared to scientists from ICAR (26.26). The total PWB score was significantly higher among ICAR scientists (99.02) compared to SAU scientists (95.99). Among PWB attributes, the scores on 'personal growth', 'positive relations with others' and 'purpose in life' were significantly higher among ICAR scientists than among those in SAUs.

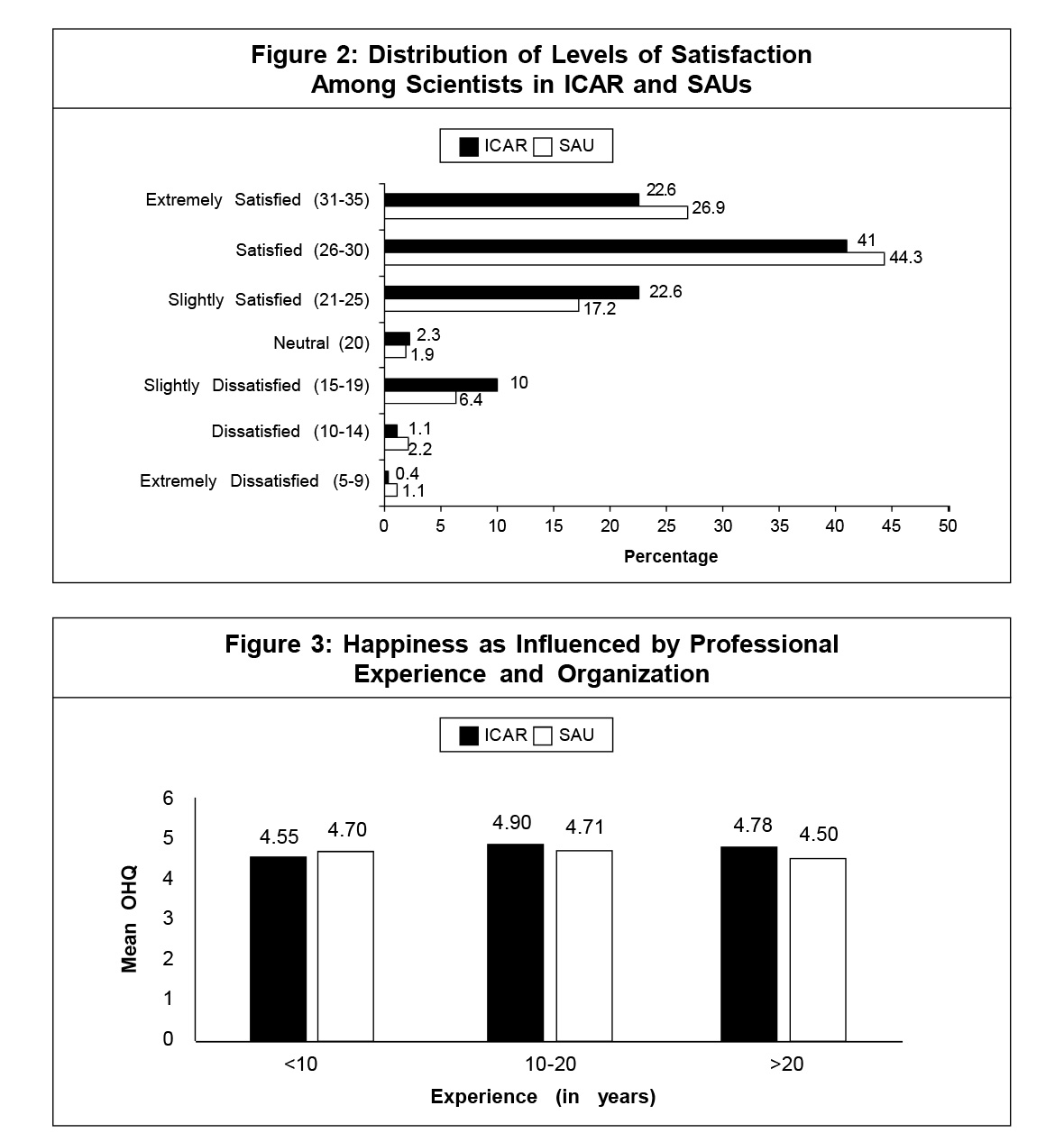

professors in SAUs), their reported mean happiness score was more (4.70) in SAU compared to ICAR scientists (4.55). Their happiness scores improved to a higher level of 4.90 and 4.71 among ICAR and SAU scientists, respectively as they reached 10-20 years of experience (usually, they become senior scientists in ICAR and associate professors in SAUs). When they crossed more than 20 years of experience (usually, they become principal scientists in ICAR and professors in SAUs), their happiness levels decreased slightly to 4.78 and 4.50 among ICAR and SAUs, respectively.

When the respondents' professional experience was less than 10 years, their life satisfaction score was more (27.13) in SAU when compared to ICAR scientists (25.46). Their life satisfaction scores increased (28.13 and 27.63 in ICAR and SAU scientists, respectively) during 10-20 years of experience. There was a slight decrease in life satisfaction scores when they have more than 20 years of experience (Figure 4). The

From the findings, it is revealed that agricultural scientists, whether they are from ICAR or SAUs, have similar personality traits and equal scores on the happiness index. However, SAU scientists have higher scores on life satisfaction and lower scores on PWB compared to ICAR scientists (Table 1). Happiness, as measured through the Oxford Happiness Questionnaire (OHQ), assesses both global happiness or current level of happiness (Argyle et al., 1995). Whereas, life satisfaction refers to an evaluation process in which a person judges the quality of their life based on their unique criteria (Shin and Johnson, 1978). Presumably, a comparison of perceived living conditions is made with a self-imposed standard or set of standards, and if the conditions meet those standards, the person reports high life satisfaction. Therefore, life satisfaction is a conscious cognitive judgment of one's life in which the criteria for judgment are up to the person (Pavot and Diener, 1993). The PWB attributes have been reported to have a strong relationship with personality traits, intellectual and physical health, healthy aging, family and occupational experiences (Ryff, 2014).

A total of 88.1% of scientists from ICAR are moderate to very happy, and 71.2% of scientists from SAUs are satisfied to extremely satisfied with their life. This indicates that a majority of scientists are happier as well as satisfied by possessing personality traits required for a career in science through which they get their happiness and life satisfaction. The results reaffirm and extend those results reported by the previous researchers, showing that scientists possess higher levels of openness and lower levels of neuroticism (Lounsbury et al., 2012) and have higher levels of subjective happiness and a sense of purpose in their life in comparison with the non-scientists (Sato, 2016).

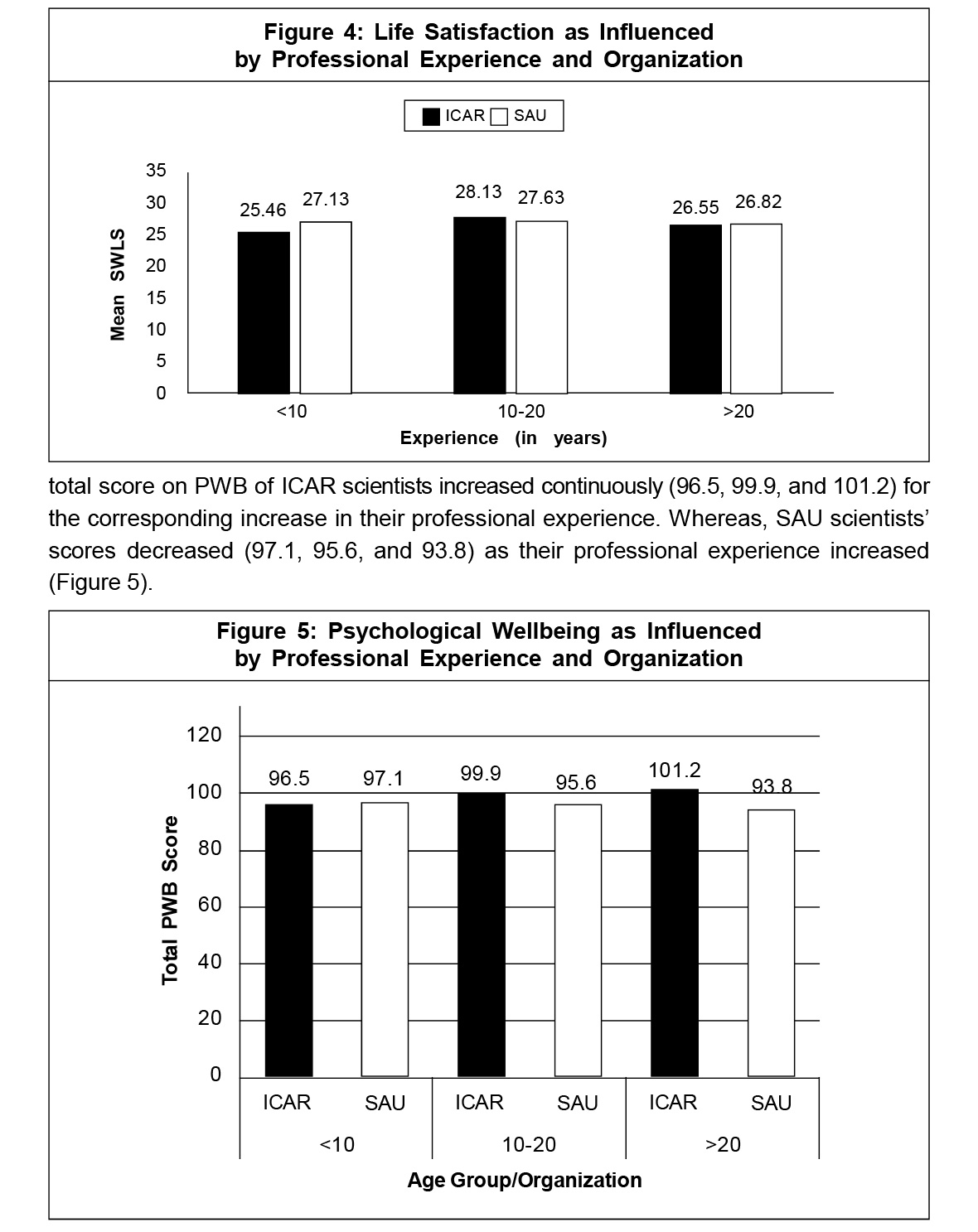

All the three wellbeing attributes, viz., happiness, life satisfaction, and PWB, are higher among the scientists in SAUs in the early stages of their career, i.e., when they have less than 10 years of experience (Figures 3, 4 and 5). Their wellbeing attributes reached a peak during their middle level of career (10-20 years of experience) and then they declined a little at later stages (more than 20 years of experience).

Higher levels of wellbeing among the SAU scientists, especially at the early stages of their career (less than 10 years), are probably due to the initial euphoria of getting placement in their native states with familiar sociocultural context, which makes them more comfortable and have feelings of happiness and satisfaction. In ICAR, scientists on selection are likely to be placed anywhere in India depending upon the vacancy positions in 101 institutions of ICAR, which makes some people not happy or unsatisfied till they get acclimatized in their organization, which may take considerable time. But once they get effectively adapted to their research environment in ICAR, their wellbeing is better than that of the scientists of SAUs.

At later stages of their career (more than 20 years of experience), decreased levels of wellbeing could be due to lack of further promotional opportunities after attaining a position of principal scientist or professor which may be affecting their motivational level (Paul et al., 2015). Apart from this, Reddy and Venkateswarlu (1989) observed that agricultural scientists who have more than 20 years of experience were reported to be less academic and service-oriented compared to their younger colleagues. Besides, it could also be due to a higher level of organizational politics, which is found to be relatively higher in SAUs when compared to the ICAR system as observed in the earlier study conducted by NAARM in India (Anwar et al., 2007).

Studies reported that organizational culture was found to influence employee happiness significantly, and they defined organizational culture as work environment, workplace trust, social interaction, and feeling appreciated (Zak, 2017; and Ficarra et al., 2020). Perceptions of the affective, cognitive, and instrumental aspects of the organizational climate at the individual level are consistently and substantially associated with happiness in the form of job satisfaction and organizational commitment (Carr

et al., 2003). Another meta-analysis found that job satisfaction and other job attitudes were consistently associated with five climate dimensions: role, job, leader, workgroup, and organization (Lok and Crawford, 2003; and Parkar et al., 2003).

Previous researchers indicated that while there is a small decline in life satisfaction with age occasionally, the relationship is eliminated when another variable such as income is controlled (Horley and Lavery, 1995). More importantly, other recent studies consistently showed that life satisfaction often increases or at least does not decrease with age (Bass, 1995; and DeNeve and Cooper, 1998). This could be because older people are healthier today and remain involved in more areas of life than the previous generations. When the researchers examined affective balance (positive minus negative affect) between age groups, the decrease in positive affect results in a lower overall mean in older cohorts, and thus older adults appear to show a decrease in happiness or general mood (Shmotkin, 1990).

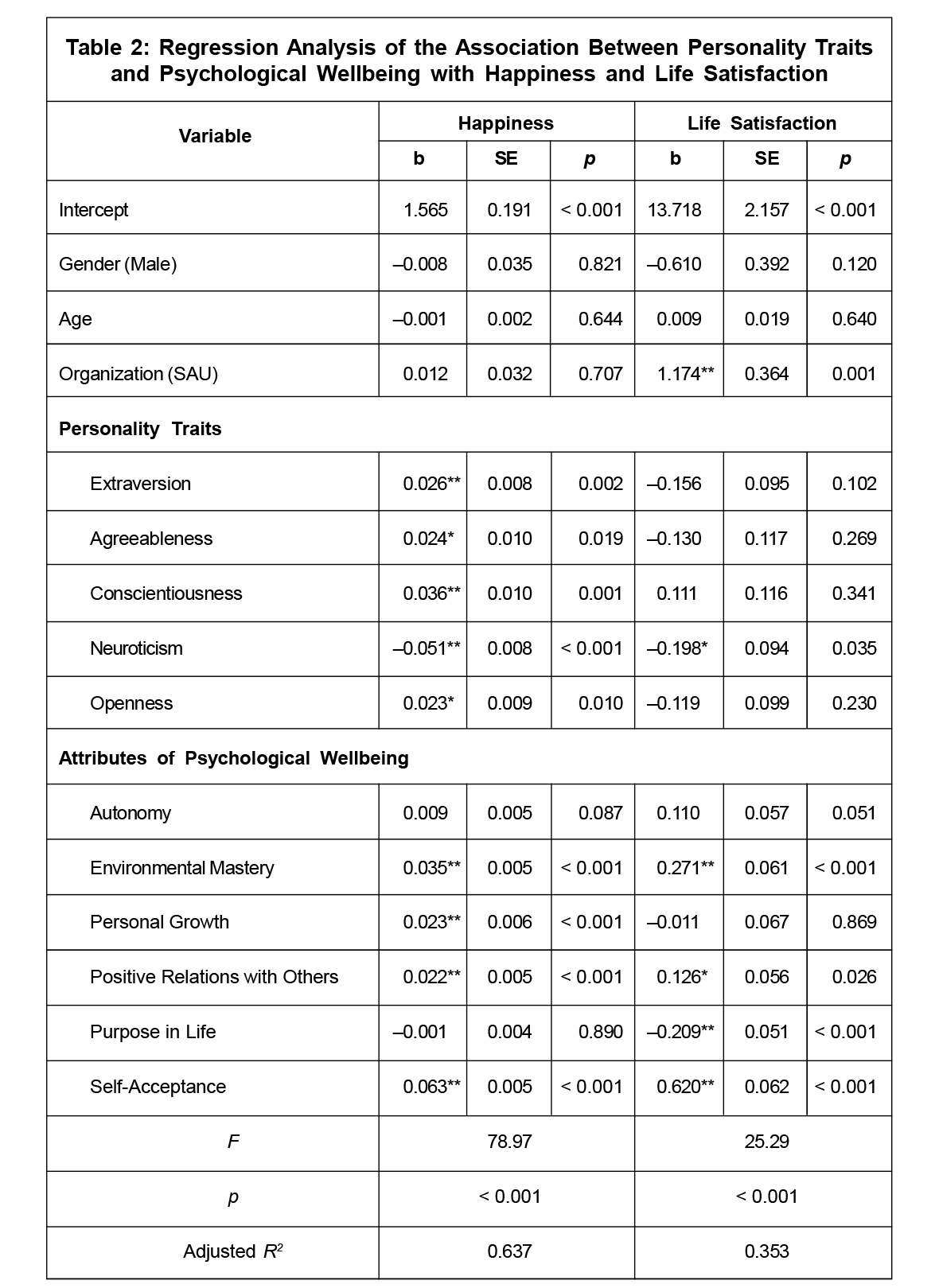

The results of the regression analysis for happiness and life satisfaction as a function of personality traits and PWB attributes are presented in Table 2. From the data, it is observed that gender, age, and organization were not contributing significantly (p > 0.1) in predicting happiness. Personality traits were found to be significantly (p > 0.05) contributing towards happiness. Except for neuroticism, all other personality traits were found to be having a positive contribution to happiness. Neuroticism has the highest association (but negative) with happiness. Among PWB attributes, environmental mastery, personal growth, positive relations with others, and self-acceptance were positively contributing towards happiness. This model is successful in capturing 63.7% of the variation in happiness. In the model for life satisfaction, organization (positively) and neuroticism (negatively) were found to be having a significant (p > 0.05) contribution. Among the attributes of PWB, self-acceptance, environmental mastery, positive relations with others significantly and positively contributed towards life satisfaction. This model successfully captured 35.3% of the variation in life satisfaction.

Studies reported that extraversion, neuroticism, and conscientiousness are associated with different aspects of wellbeing (Schmutte and Ryff, 1997; DeNeve and Cooper, 1998; and Sirgy, 2021) and may differentiate people who scored high on each PWB and SWB from people who scored low on PWB and SWB (Keyes et al., 2002). Alves et al. (2019) reported that personality factors play an important role in personal and work happiness and life satisfaction by influencing networks and organizational trust. Suldo et al. (2015) reported that roughly 47% of the variation in life satisfaction was accounted for by the Big-Five personality traits. People with high neuroticism traits possess a low level of PWB because of irrational ideas, inability to regulate their impulses and cope suitably with stress (Schmutte and Ryff, 1997; and Ramesh, 2017). The findings from Costa and McCrae (1980) revealed that satisfaction with life is said to have a relationship with a high level of extraversion and a low level of neuroticism. In a study on scientists, neuroticism was found to be negatively associated with emotional intelligence and happiness (Ramesh, 2020). The data from 30 countries confirmed that interaction between extraversion and neuroticism was a significant predictor of satisfaction with life, and such association was not found significant with happiness (Lynn and Steel, 2006).

Conclusion

From the study, it is inferred that a majority of agricultural scientists are happier and well-satisfied by possessing personality traits required for a career in science through which they get their happiness and life satisfaction. Organizations where scientists work (ICAR versus SAUs) have an impact on their wellbeing. Even though at the beginning of their career, scientists from SAUs were reported to have higher wellbeing, yet in the long run, ICAR scientists were found to sustain their levels of happiness and PWB. Agricultural scientists' happiness can be predicted by their Big-Five personality traits and PWB attributes to the extent of 63.7%, whereas life satisfaction can be predicted by their organization, neuroticism, and certain attributes of PWB to an extent of 35.3%.

Implications: The implications of the study include selection, training, and implementing possible organizational interventions to build a happy workforce environment, which is a prerequisite for any scientific endeavor. In the workplace, happiness is influenced by both shortlived events and chronic conditions at work, the nature of the job, and the organization. It is also influenced by stable attributes of individuals such as personality, as well as the match between what the job/organization offers and the expectations, needs, and preferences of the person. Understanding these factors that contribute to happiness, along with recent research on volitional acts to enhance happiness, offers some potential levers for enhancing happiness in the workplace. Since personality and PWB are relatively stable over time and predict employees' happiness and productivity, these traits can also be used in the selection and recruitment criteria. Training employees and providing the necessary resources make them feel that their organization is invested in them. Trained scientists are often more satisfied and motivated than their peers who did not receive regular training. Organizational interventions that promote happiness and aim to maintain a research environment, such as autonomy, innovation, leadership style, trust, recognition, fairness and support, and provision of sufficient funds for research should be taken care of for higher productivity at the individual level.

Limitations and Future Scope: Considering the exploratory nature of this study, to our information, this may be the primary investigation to assess the personality and wellbeing traits of agricultural scientists. Thus, the outcome cannot be generalized because of the sample size and scarcity of variables examined as potential predictors of happiness and life satisfaction, and the restricted battery of tests employed in the present investigation to assess wellbeing. Further investigations are necessary to explore the role of other factors in predicting measures of wellbeing. Thus, additional research is required to clarify whether the current findings can be replicated using other tools for estimating wellbeing, validating across cultures.

References

- Alves L, Neira I and Rodrigues H S (2019), "Context and Personality in Personal and Work-Related Subjective Well-Being: The Influence of Networks, Organizational Trust and Personality", Psychological Studies, Vol. 64, No. 2, pp. 173-186.

- Anwar M M, Manikandan P, Rao R V S and Rao K H (2007), "Leadership Styles and Effectiveness in ICAR and SAU's", pp. 1-127, Final Project Report, ICAR-NAARM, Hyderabad, India.

- Argyle M, Martin M and Crossland J (1989), "Happiness as a Function of Personality and Social Encounters", in J P Forgas and J M Innes (Eds.), Recent Advances in Social Psychology: An International Perspective, Elsevier, North-Holland.

- Argyle M, Martin M and Lu L (1995), "Testing for Stress and Happiness: The Role of Social and Cognitive Factors", in C D Spielberger and I G Sarason (Eds.), Stress and Emotion, pp. 173-187, Taylor & Francis, Washington, DC.

- Balgiu B A (2018), "The Psychometric Properties of the Big Five Inventory-10 (BFI-10) Including Correlations with Subjective and Psychological Well-Being", Global Journal of Psychology Research: New Trends and Issues, Vol. 8, No. 2, pp. 61-69.

- Bass S A (1995), Older and Active: How Americans over 55 are Contributing to Society, Yale University Press, New Haven.

- CAERT (2006), "The Importance of Agricultural Research", Centre for Agricultural Research & Technology. AgEdLibrary.com, pp.1-8, https://www.carlisle.k12.ky.us/userfiles/1044/ Classes/ 6685/070008.pdf

- Carr J Z (2004), Positive Psychology: The Science of Happiness and Human Strength, Brunner-Routledge, New York.

- Carr J Z, Schmidt A M, Ford J K and DeShon R P (2003), "Climate Perceptions Matter: A Meta-Analytic Path Analysis Relating Molar Climate, Cognitive and Affective States, and Individual Level Work Outcomes", Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 88, No. 4, pp. 605-619.

- Costa P T and McCrae R R (1980), "Influence of Extraversion and Neuroticism on Subjective Well-Being: Happy and Unhappy People", Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 38, No. 4, pp. 668-678.

- DeNeve K M and Cooper H (1998), "The Happy Personality: A Meta-Analysis of 137 Personality Traits and Subjective Well-Being", Psychological Bulletin, Vol.124, No. 2, pp. 197-229.

- Diener E (2000), "Subjective Well-Being: The Science of Happiness and a Proposal for a National Index", American Psychologist, Vol. 55, No.1, pp. 34-43.

- Diener E, Emmons R A, Larsen R J and Griffin S (1985), "The Satisfaction with Life Scale", Journal of Personality Assessment, Vol. 49, No.1, pp. 71-75.

- Feist G J (2006), "The Past and Future of the Psychology of Science", Review of General Psychology, Vol. 10, No. 1, pp. 92-97.

- Feist G J and Gorman M E (1998), "The Psychology of Science: Review and Integration of a Nascent Discipline", Review of General Psychology, Vol. 2, No.1, pp. 3-47.

- Ficarra L, Rubino M J and Morote E S (2020), "Does Organizational Culture Affect Employee Happiness", Journal of Leadership and Instruction, Vol. 9, No. 2, pp. 38-47.

- Fisher C D (2010), "Happiness at Work", International Journal of Management Review, Vol. 12, No. 4, pp. 384-412.

- Fredrickson B L (2001), "The Role of Positive Emotions in Positive Psychology: The Broaden-and-Build Theory of Positive Emotions", American Psychologist, Vol. 56, No. 3, pp. 218-226.

- Gavin J H and Mason R O (2004), "The Virtuous Organization: The Value of Happiness in the Workplace", Organizational Dynamics, Vol. 33, No. 4, pp. 379-392.

- Gosling S D, Rentfrow P J and Swann W B Jr (2003), "A Very Brief Measure of the Big-Five Personality Domains", Journal of Research in Personality, Vol. 37, No. 6, pp. 504-528.

- Hills P and Argyle M (2002), "The Oxford Happiness Questionnaire: A Compact Scale for the Measurement of Psychological Well-Being", Personality and Individual Differences, Vol. 33, No. 7, pp. 1073-1082.

- Horley J and Lavery J J (1995), "Subjective Well-Being and Age", Social Indicators Research, Vol. 34, No. 3, pp. 275-282.

- ICAR (2021), "Indian Council of Agricultural Research", New Delhi, India, https://icar.org.in/content/about-us

- Isa K, Tenah S S, Atim A and Jam N A M (2019), "Leading Happiness: Leadership and Happiness at a Workplace", International Journal of Recent Technology and Engineering, Vol. 8, No. 3, pp. 6551-6553.

- Keyes C L M, Shmotkin D and Ryff C D (2002), "Optimizing Well-Being: The Empirical Encounter of Two Traditions", Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 82, No. 6, pp. 1007-1022.

- Lok P and Crawford J (2003), "The Effect of Organizational Culture and Leadership Style on Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment", Journal of Management and Development, Vol. 23, No. 4, pp. 321-338.

- Lounsbury J W, Foster N, Patel H et al. (2012), "An Investigation of the Personality Traits of Scientists versus Non-Scientists and their Relationship with Career Satisfaction", R & D Management, Vol. 42, No. 1, pp. 47-59.

- Ludwig A (1995), The Price of Greatness: Resolving the Creativity and Madness, Guilford, New York.

- Lynn M and Steel P (2006), "National Differences in Subjective Well-Being: The Interactive Effects of Extraversion and Neuroticism", Journal of Happiness Studies, Vol.7, No. 2, pp. 155-165.

- Manjunath L (2011), "Determinates of Scientific Productivity of Agricultural Scientists", Indian Research Journal of Extension Education, Vol. 11, No. 1, pp. 7-12.

- Parker C P, Baltes B B, Young S A et al. (2003), "Relationships Between Psychological Climate Perceptions and Work Outcomes: A Meta-Analytic Review", Journal of Organizational Behaviour, Vol. 24, No. 4, pp. 389-416.

- Paul S, Vijayaraghavan K, Premalata Singh and Burman R R (2015), "Research Productivity of Agricultural Scientists: Evidence from High Performing and Low Performing Institutes", Indian Journal of Agricultural Sciences, Vol. 85, No. 4, pp. 487-492.

- Paul S, Vijayaraghavan K, Premalata Singh et al. (2017), "Determinants of Research Productivity of Agricultural Scientists: Implications for the National Agricultural Research and Education System of India", Current Science, Vol. 112, No. 2, pp. 252-257.

- Pavot W G and Diener E (1993), "Review of the Satisfaction with Life Scale", Psychological Assessment, Vol. 5, No. 2, pp. 164-172.

- Pryce-Jones J (2010), "Happiness at Work, Maximizing Your Psychological Capital for Success", Journal of Workplace Behaviour and Health, Vol. 26, No. 2, pp. 271-273.

- Ramesh P (2017), "Emotional Intelligence and Perceived Stress among Scientists in Agricultural Research Service", The IUP Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 16, No. 2, pp. 70-79.

- Ramesh P (2020), "Personality, Emotional Intelligence and Happiness: A Study of Scientists and Non-Scientists", The IUP Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 19, No. 4, pp. 22-39.

- Ramesh P and Rao R V S (2020), "Role of Emotional Intelligence on Organizational Effectiveness: A Study Among Scientific Personnel in the National Agricultural Research and Educational system (NARES) in India", Journal of Organization & Human Behaviour, Vol. 9, Nos.1&2, pp. 10-20.

- Ramesh P, Yashavanth B S and Rao R V S (2021), "Personality and Well-Being Traits of Agricultural Scientists: Assessment, Correlations, and Prediction", Journal of Organization & Human Behaviour, Vol. 10, No. 3, pp. 9-21.

- Rammstedt B and John O P (2007), "Measuring Personality in One Minute or Less: A 10-Item Short Version of the Big Five Inventory in English and German", Journal of Research in Personality, Vol. 41, No. 1, pp. 203-212.

- Rao, R V S, Rao, K H, Yashavanth B S, Indu Priya M, Anwar M M and Srinivasa Rao Ch (2017). "Strategic Thinking Ability of Scientists in the Indian Agricultural Research and Education System". International Journal of Knowledge and Research in Management & E-Commerce, Vol. 7, No. 1, pp. 1-7.

- Rao R V S, Alok Kumar, Rao K H, Yashavanth B S, Indu Priya M, Anwar M M and Srinivasa Rap Ch (2021). "Leadership Styles of the Professionals from the National Agricultural Research and Education System", Indian Journal of Extension Education, Vol. 57, No.1, pp. 105-109.

- Rawlings D and Locarnini A (2008), "Dimensional Schizotypy, Autism and Unusual Word Associations in Artists and Scientists", Journal of Research on Personality, vol. 42, No. 2, pp. 465-471.

- Reddy K P and Venkateswarlu K (1989), "Agricultural Scientists: What Do They Prefer in Their Jobs", Indian Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 26, No. 1, pp.41-47.

- Ryff C D (1989), "Happiness is Everything, or Is It? Explorations on the Meaning of Psychological Well-Being", Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 57, No. 6, pp. 1069-1081.

- Ryff C D (2014), "Psychological Well-Being Revisited: Advances in the Science and Practice of Eudaimonia", Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, Vol. 83, pp.10-28.

- Ryff C D and Keyes C L M (1995), "The Structure of Psychological Well-Being Revisited", Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 69, No. 4, pp. 719-727.

- Ryff C D and Singer B H (2008), "Know Thyself and Become What You Are: A Eudaimonic Approach to Psychological Well-Being", Journal of Happiness Studies, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 13-39.

- Sato W (2016), "Scientists' Personality, Values and Well-Being", SpringerPlus, Vol. 5, No. 4, pp. 613, 1-7.

- Shmotkin D (1990), "Subjective Well-Being as a Function of Age and Gender: A Multivariate Look for Differentiated Trends", Social Indicators Research, Vol. 23, No. 2, pp. 201-230.

- Schmutte P S and Ryff C D (1997), "Personality and Well-Being: Re-Examining Methods and Meanings", Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 73, No. 3, pp. 549-559.

- Shadish W R Jr, Houts A C, Gholson B and Neimeyer R A (1989), "The Psychology of Science: An introduction", in B Gholson, W R Shadish Jr, R A Neimeyer and A C Houts (Eds.), Psychology of Science: Contributions to Meta-Science, pp. 1-16, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Shin D C and Johnson D M (1978), "Avowed Happiness as an Overall Assessment of the Quality of Life", Social Indicators Research, Vol. 5, Nos. 1-4, pp. 475-492.

- Sirgy M J (2021), "Effects of Personality on Wellbeing", in The Psychology of Quality of Life. Social Indicators Research Series, Vol 83. No. 1, pp. 6-9, Springer, Cham.

- Suldo S M, Minch D R and Hearon B V (2015), "Adolescent Life Satisfaction and Personality Characteristics: Investigating Relationships Using a Five-Factor Model", Journal of Happiness Studies, Vol. 16, No. 4, pp. 965-983.

- Wesarat P, Sharif M Y and Majid A H A (2015), "A Conceptual Framework of Happiness at the Workplace", Asian Society of Science, Vol. 11, No. 2, pp. 78-88.

- Wolpert L and Richards A (1997), Passionate Minds: The Inner World of Scientists, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Youssef C M and Luthans F (2007), "Positive Organizational Behavior in the Workplace: The Impact of Hope, Optimism, and Resilience", Journal of Management, Vol. 33, No. 5, pp. 774-800.

- Zak P J (2017), "Organizational Trust: The Neuroscience of Trust: Management Behaviors that Foster Employee Engagement", Harvard Business Review, pp. 1-8, https://www.emcleaders.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/hbr-neuroscience-of-trust.pdf