October'23

The IUP Journal of Organizational Behavior

Archives

Cultural Intelligence and Task Performance: Mediating Role of Cross-Cultural Adjustment in Indian IT Firms

Kishore Babu Addagabottu

Research Scholar, Department of Human Resource Management, Acharya Nagarjuna University,

Nagarjuna Nagar, Guntur District, Andhra Pradesh, India; and is the corresponding author.

E-mail: kishore.addagabottu@gmail.com

Nagaraju Battu

Associate Professor, Department of HRM, Director, Centre for HRD, Acharya Nagarjuna University,

Nagarjuna Nagar, Guntur District, Andhra Pradesh, India. E-mail: battunraju@yahoo.co.in

The main aim of the study is to examine the mediating role of cross-cultural adjustment in the relationship between cultural intelligence and task performance in Indian IT firms. The study was conducted among the employees in supervisory positions (i.e., team leaders, project managers, admin managers, and functional heads) and team members from other states of India at information technology (IT) companies in Chennai and Bengaluru. Snowball sampling method was adopted to select the sample from the given population. Primary data was gathered through Google Forms and analyzed using IBM SPSS 24.0 and Smart PLS 4.0. The findings indicate that cultural intelligence has a strong positive direct effect on task performance and a strong positive indirect effect on task performance through partial mediation of cross-cultural adjustment. Therefore, it is concluded that culturally intelligent leaders quickly adapt to cross-cultural environments and demonstrate better task performance in the workplace.

Introduction

The growth of information technology (IT) has made the world a global village. And in India, IT industry accounted for 7.4% of India's GDP in FY22, and it is anticipated to contribute 10% to India's GDP by 2025 (IBEF, 2023). Due to the rapid development of the IT sector in India, there has been movement of employees from one Indian state to another, blurring, in the process, the cultural borders among people. However, this elimination of cultural borders among those employed in various IT companies in different states of India has created for IT managers the challenge of handling people from different cultures.

India is home to diverse (region-based) cultures. Cultural characteristics, including race, gender, age, color, physical ability, and ethnicity, are examples of diversity. Sikhism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Hinduism all originated in India. Cultures differ across various religions. Employees with various cultural backgrounds in an organization frequently experience cultural shocks and misunderstandings due to cultural differences. As a result, managing regional cultural diversity within the organization is a challenge for Indian organizations. Culturally intelligent employees can adjust to the diverse culture and perform their jobs better than other employees (Kodwani, 2012; Jyoti and Kour, 2015, 2017a and 2017b; and Kour and Jyoti, 2022). Hence, large IT companies have to be prepared to handle employees belonging to diverse cultural backgrounds. Hence, there is an essential requirement for organizations to pay attention to cultural diversity and inclusivity. Managing diversity is a vital element for effective people management, which in turn enhances workplace productivity. Therefore, IT managers should learn the art of managing diversity, which is a continuing process. For IT companies to be successful in today's competitive global market, they must nurture a new class of managers who can focus beyond the surface-level cultural variances and function efficiently in circumstances characterized by cultural diversity. Hence, IT managers should possess cultural intelligence-a tool that can increase an individual's ability to interact with people outside their cultures (Christine et al., 2009; and Presbitero and Toledano, 2018).

Culturally intelligent individuals have the talent to interact efficiently with persons from different cultures (Ang et al., 2007). These individuals can sense, assimilate and act on cultural cues properly in circumstances characterized by cultural diversity. This indeed helps people to become more operative in decision-making, collaborating and negotiating across cultures. Hence, culturally intelligent managers are seen as a source of competitive advantage and strategy.

Culturally intelligent IT managers can better understand and network with employees of different cultures, which increases the performance of the individuals in their teams (Kodwani, 2012; Jyoti and Kour, 2015; and Presbitero and Toledano, 2018). This study seeks to investigate the impact of cultural intelligence on employees' task performance in two selected cities, viz., Chennai and Bengaluru. Further, the study examines the mediating role of cultural adjustment between cultural intelligence and task performance in the Indian context.

Literature Review

Relationship Between Cultural Intelligence (CQ) and Task Performance (TP)

According to Earley and Ang (2003) and Ang et al. (2007), cultural intelligence is the capacity of an individual to successfully adjust to novel and unfamiliar cultural contexts and to easily and productively function in circumstances marked by cultural diversity. According to Ang et al. (2007) and Ramalu et al. (2011), it is a multidimensional construct made up of the following four dimensions: cognitive, metacognitive, motivational, and behavioral. The cognitive dimension is associated with general cultural knowledge, including understanding the legal, economic, and social systems as well as the fundamental frameworks of other cultures' and subcultures' values. Ang et al. (2007) confirmed that employees who are better conscious of their atmosphere (meta-cognitive CQ) were able to acclimate their behavior accordingly (behavioral CQ), which in turn leads to improved considerateness and culturally suitable role expectations. Culturally intelligent individuals understand anticipated role behaviors in circumstances categorized by cultural diversity (Ang et al., 2007). Likewise, motivational and behavioral CQ is connected to task performance (Kumar et al., 2008; and Ng et al., 2012). Personnel with high-motivational CQ must have greater job performance because they make direct efforts toward acquiring the mandatory role anticipations, even when role sender cues are confusing due to cultural differences (Stone-Romero et al., 2003; and Chen et al., 2012). Culturally intelligent persons better understand and network with employees of different cultures, which increases performance. Employees with a higher level of CQ have the competencies to collect data or information to draw conclusions and enact cognitive, emotive or behavioral actions in response to cultural cues of the host country (Earley and Ang, 2003). Cultural intelligence lessens misinterpretations in role anticipations, and which ultimately improves task performance.

Task performance is known as a function of knowledge, skills, talents and inspiration that focuses on a specific role-behavior employee, such as prescribed task accountability (Campbell, 1999). Therefore, this phenomenon has an optimistic association with cultural intelligence. Cultural intelligence, on the other hand, represents a person's capability to function positively in given circumstances characterized by cultural diversity.

Gardner's (1983) Multiple Intelligences Theory and Sternberg and Detterman's (1986) Multiple Intelligences Theory are the sources of the idea of CQ. The Individual Differences Theory of Motowidlo et al. (1997) and Gardner's Theory of Multiple Intelligence serve as the foundation for the theoretical framework of the current study. It is stated that CQ is the theoretical expansion of Gardner's Multiple Intelligence Theory. As CQ is a manifestation of intelligence, Earley and Ang (2003) argued that it is a more proximal predictor of performance outcomes. Further, evidence that CQ is a strong predictor of job performance in a cross-cultural context has been established by the results of earlier studies (Ang et al., 2007; Kumar et al., 2008; Ng et al., 2012; Ramalu et al., 2012; Jyoti and Kour, 2015 and 2017b; and Kour and Jyoti, 2022). A high degree of CQ enables workers to smoothly integrate into any setting and carry out their duties. Therefore, it is expected that in IT businesses, CQ is a significant determinant of task performance.

Relationship Between CQ and Cross-Cultural Adjustment (CA)

CA is stated as the degree of psychological comfort or ease an individual has in the host culture (Black and Stephens, 1989; and Gregersen and Black, 1990). CQ is a device used by individuals to enhance their ability to network with people who are external to their cultures. It denotes a person's competence to function efficiently in circumstances characterized by cultural diversity (Earley and Ang, 2003; Earley and Peterson, 2004; and Ang and Van Dyne, 2008). Various studies on CA show that there is a positive relationship between CQ and CA (Lee and Sukoco, 2010; and Ramalu et al., 2010 and 2011). It is also established that CQ has a direct effect on CA, which certainly helps individuals to adjust more effortlessly to the host environment (Earley and Ang, 2003). Indian IT managers employed in supervisory positions have to work with IT employees coming from various cultural backgrounds of India, marked by different languages, beliefs and value systems (Banerjee, 2013).

Ramalu et al. (2010) stated that all four dimensions of CQ are closely associated with CA, i.e., metacognitive, cognitive, behavioral and motivational intelligence dimensions of CQ are established to have a positive association with all three dimensions of CA, i.e., general adjustment, work adjustment and interaction adjustment. And CQ's relationship with CA helps employees in the cultural learning process, which in turn creates intrinsic interest in other cultures. IT managers with high cultural intelligence are found to better adjust themselves to the host culture environment.

Relationship Between CA and Task Performance (TP)

TP is the function of knowledge, skills, talents and inspiration directed towards individuals' prescribed role behavior, such as formal task accountabilities (Campbell, 1999). TP comprises all behavior and skills required by an employee for carrying out the working procedure, and also denotes the knowledge and evidence about the principles associated with work performance (Bess, 2001).

According to Ramalu et al. (2011), task performance is target-driven and sometimes referred to as in-role behavior. Therefore, this phenomenon has a positive link with CA, i.e., employees who can adjust themselves in cross-cultural circumstances are found to have enhanced talent to accomplish the given job to them (Kumar et al., 2008). The success of IT managers posted in different states depends on CA, as it is one of the key determinants (Ramalu et al., 2012). CA also decreases the degree of pressure and strain, which in turn increases one's performance (Caligiuri, 1997; and Bhaskar-Shrinivas et al., 2005).

IT managers posted in different states in the country have to make cultural and work-related adjustments to various workplace standards, particular work responsibility, performance standards, and operational style of their immediate superior. Therefore, CA is essential to accomplish the in-role task assigned to a person or individual working in a host cultural location.

CQ, CA and TP

CA provides a degree of psychological comfort that helps employees to stay relaxed in a new culture (Demes and Geeraert, 2014). As stated by various researchers, this phenomenon mediates the association between CQ and job performance (Lee and Sukoco, 2010; and Ramalu et al., 2012). Culturally intelligent IT managers have the capability to achieve better due to their competence to adjust to a different cultural environment (Huff et al., 2014; and Lee and Kartika, 2014).

Shaffer et al. (2006), Wang and Takeuchi (2007) and Kim and Slocum (2008) too stressed the mediating role of CA between individual variances and performance of employees. Jyoti and Kour (2015) noted the association between CQ and TP, mediated by CA.

The capacity to handle stress related to uncertainty in an alien culture will display a healthier CA. CA mediates the optimistic effect of CQ on job performance (Ramalu

et al., 2012). A mediating variable was helpful in clarifying the causal association between a predictor and a criterion (Baron and Kenny, 1986).

Hypotheses

The following hypothesis have been formulated for this study:

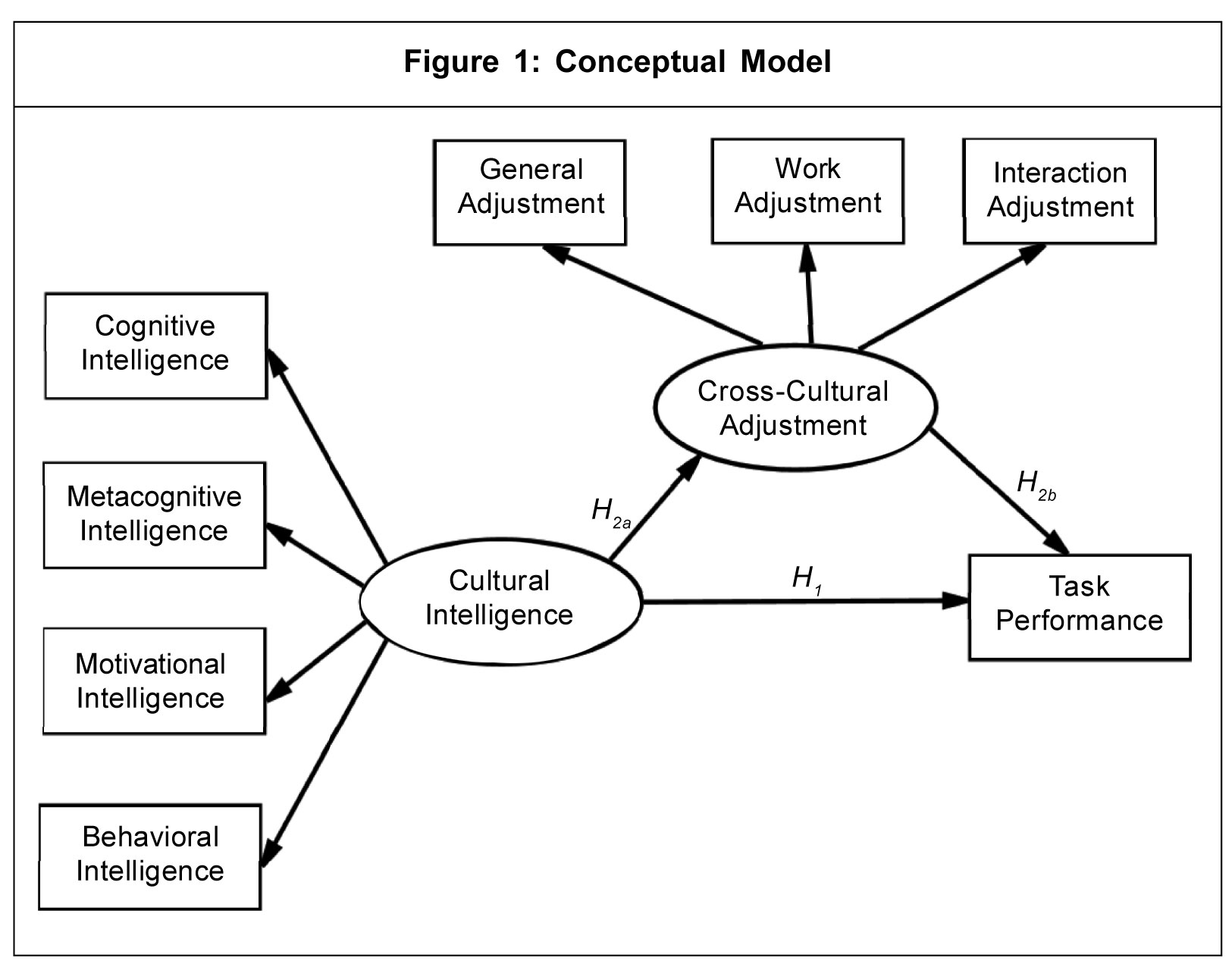

- H1: Cultural intelligence positively impacts task performance.

- H2a: Cultural intelligence positively influences cross-cultural adjustment.

- H2b: Cross-cultural adjustment is positively related to task performance.

- H3: Cross-cultural adjustment mediates the relationship between cultural intelligence and task performance.

Data and Methodology

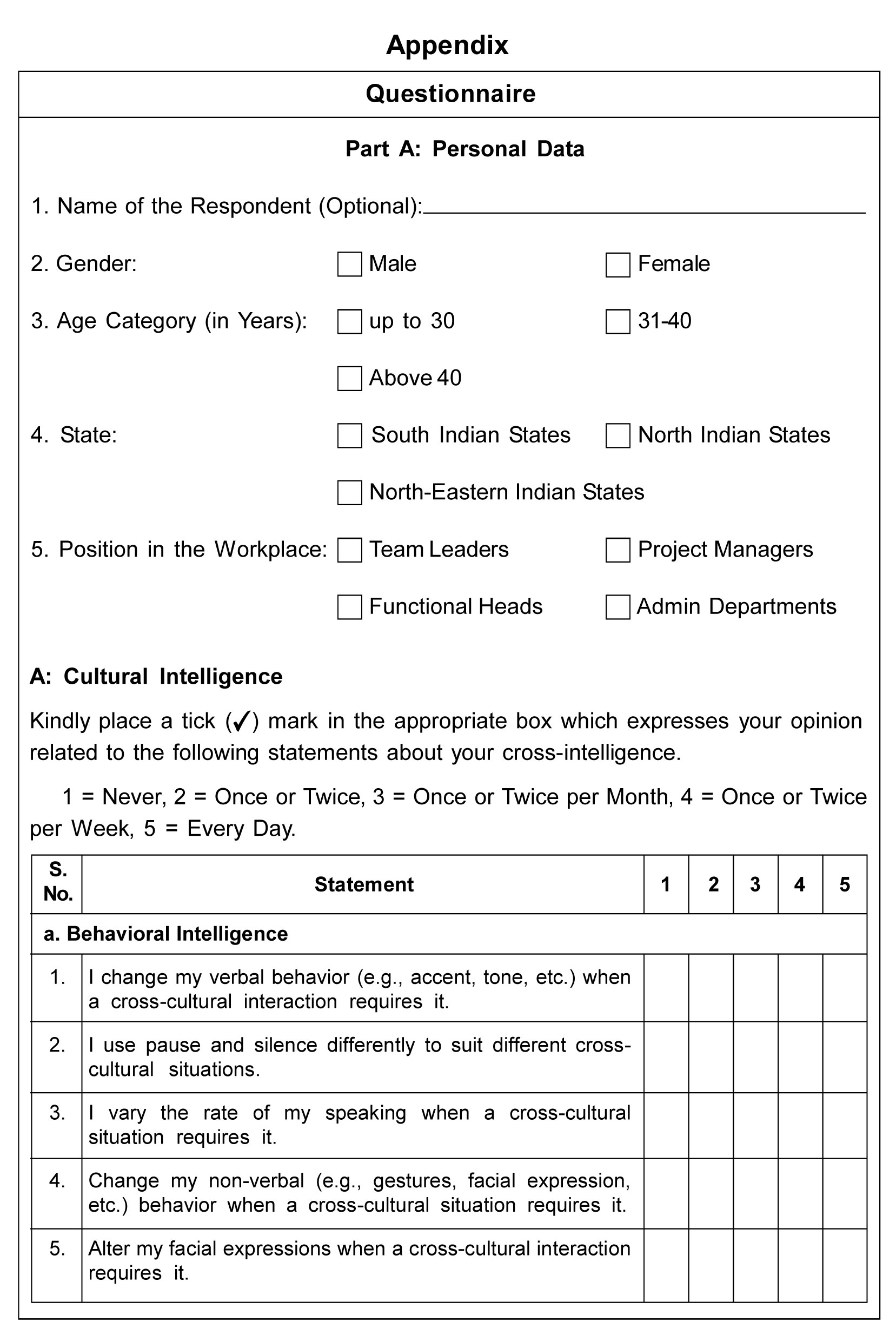

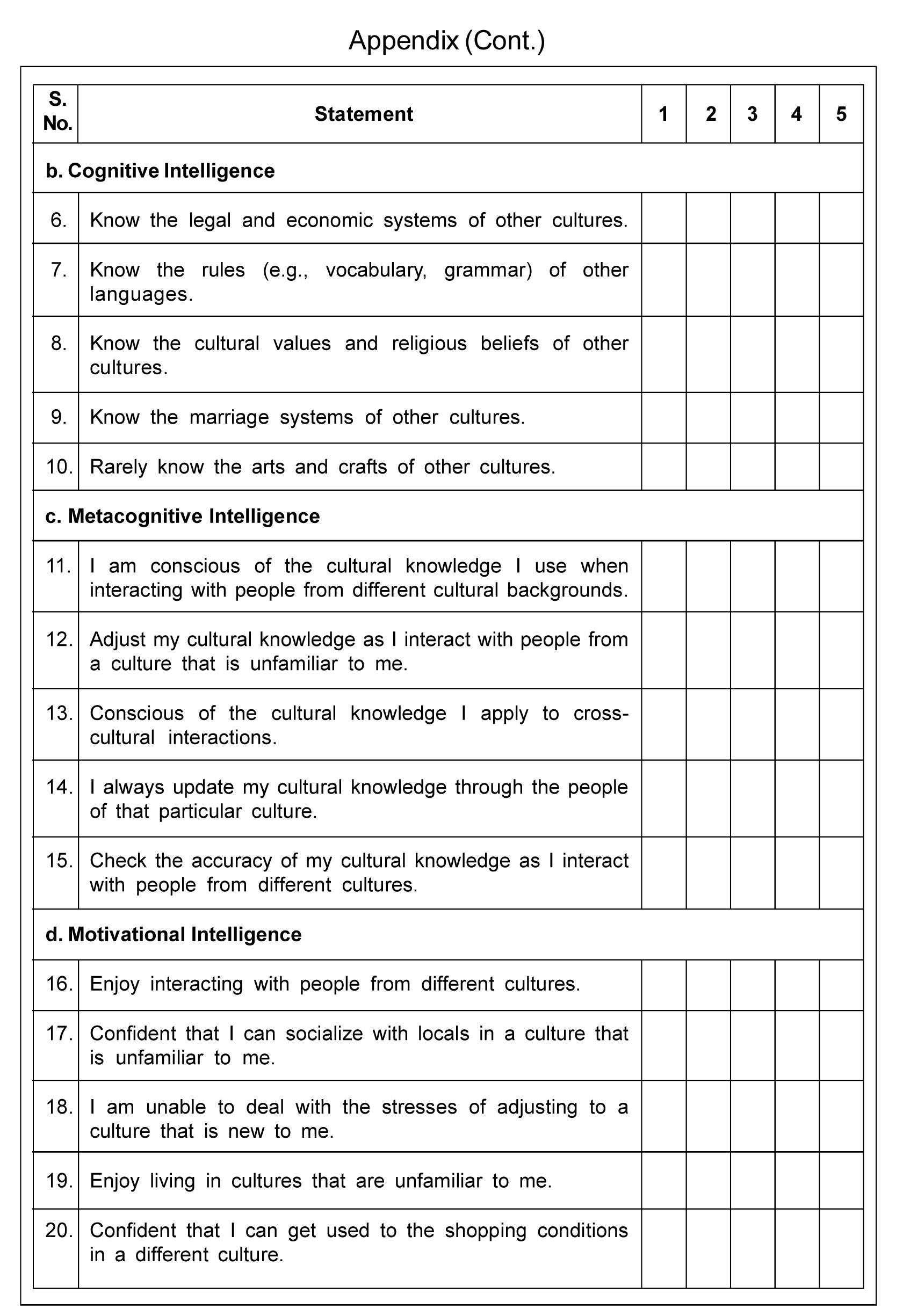

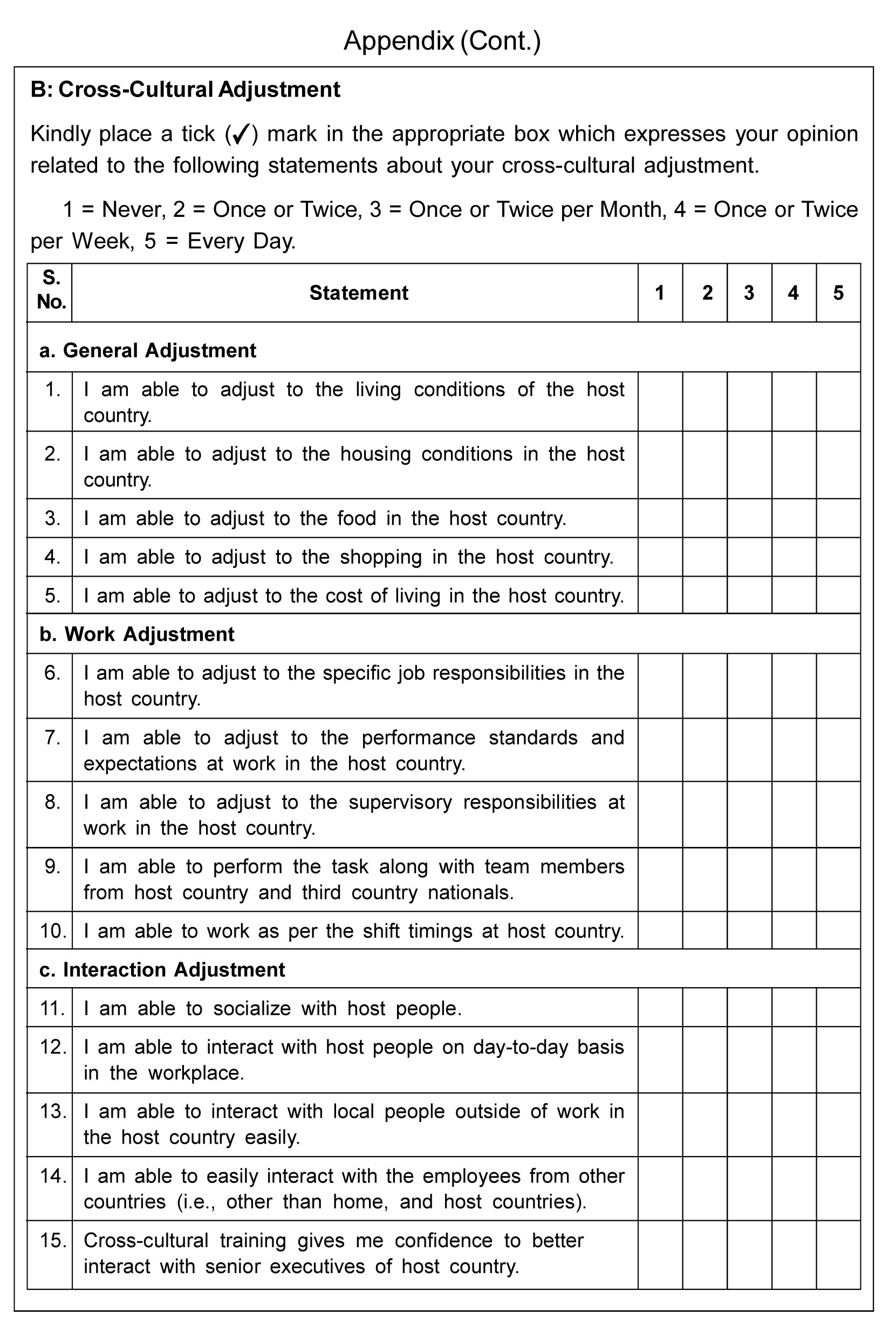

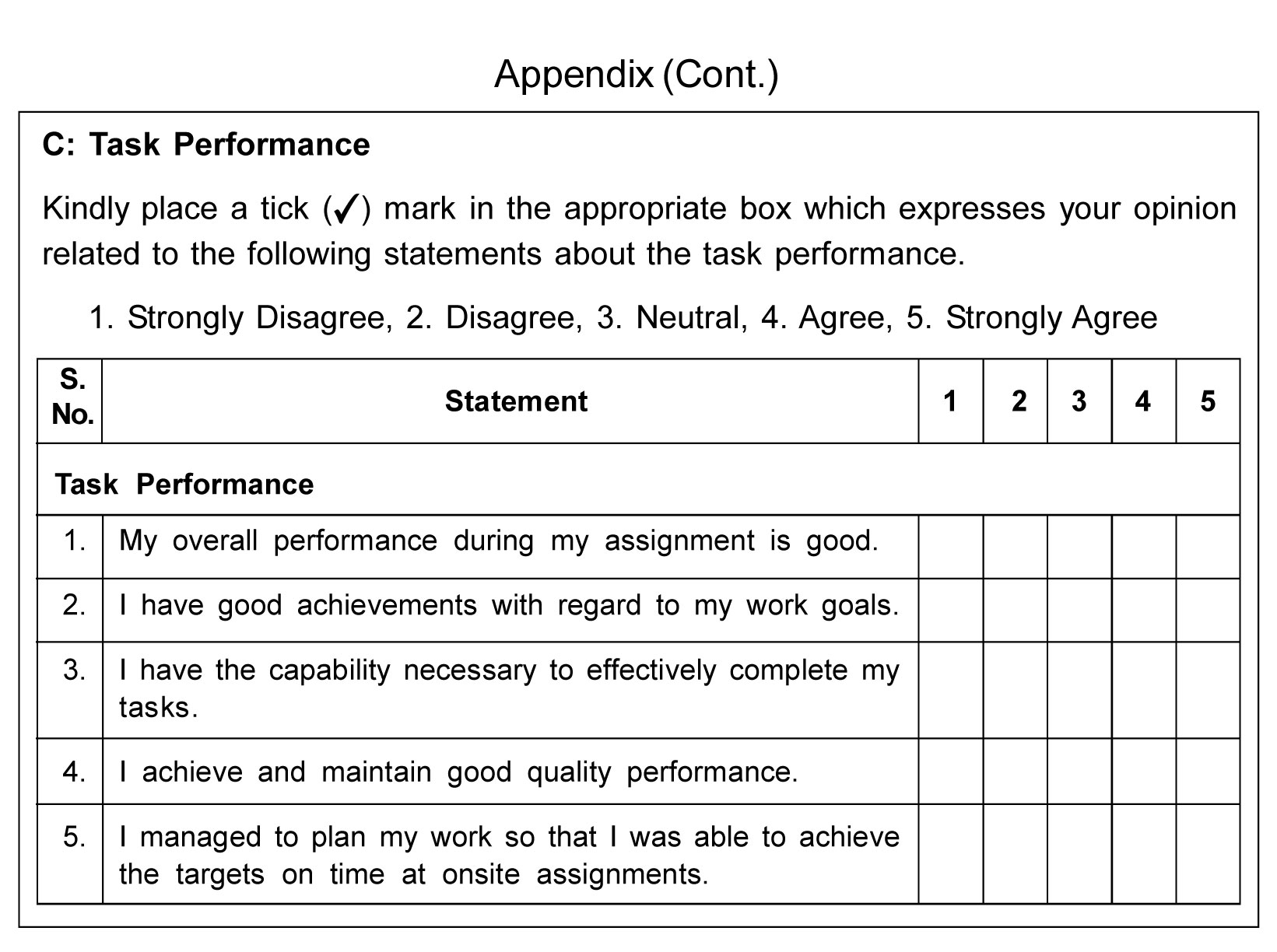

The primary data was gathered through a structured questionnaire (see Appendix), distributed via Google Forms among employees working in supervisory positions (i.e., team leaders, project managers, admin managers, and functional heads) and having team members from other states of India at IT companies in Chennai and Bengaluru. The IT industry employs talent from different cultures from across the country. Hence, this study on cross-cultural management in a domestic context was conducted in selected IT companies. This study was conducted during the period April-June 2023 (i.e., three months). Snowball sampling method was adopted to select the samples from the target population. The sample size was 429.

Measures

CQ Scale: 20-item CQ scale with four dimensions, namely, metacognitive (5 items), cognitive (5 items), motivational (5 items), and behavioral (5 items) was used. Cronbach's

alpha of the scale was 0.853. The sample items included "I enjoy living in cultures that are unfamiliar to me" (Ang et al., 2007).

CA Scale: 15-item CA scale with three dimensions, namely, general (5 items), work (5 items), and interaction adjustments (5 items) was used. Cronbach's

alpha of the scale was 0.794. The sample items included "Adjust myself to the conditions in state where I am posted" (Black and Porter, 1991).

TP Scale: Four items of the Expatriate Performance scale, developed by Black and Porter (1991), was adopted to measure the TP. Cronbach's alpha of the scale was 0.839. The sample item included "My overall performance during my assignment is good" (Black and Porter, 1991).

All these scales have been measured using Likert's five-point scale to maintain consistency.

Demographic Profile of the Sample

The sample comprised 52% team leaders, 12% project managers, 21% functional heads, and 15% from admin department. With regard to gender, 58% were males and 42% females. 56% were from South Indian states, 33% from North Indian states, and 11% from North-eastern states. A significant proportion (47%) of them were aged between 31 and 40 years, around one-third (34%) up to 30 years, and about one-fifth (19%) more than 40 years.

Results and Discussion

Common Method Bias (CMB) and Multicollinearity

CMB typically happens when data is collected from a single data source using a common scale. Using Harman's one factor test and exploratory factor analysis (EFA), CMB was validated in this study. To confirm the absence of CMB, Podsakoff et al. (2003) stated that the overall variation of a single factor should be less than 50%. The EFA results produce eight factors, the first of which accounts for 35.26% (less than 50%) of the variation. Thus, it is established that CMB has no discernible impact on the study. Additionally, the data's multicollinearity is confirmed in SmartPLS as suggested by Kock's (2015) recommendation by estimating the variance inflation factor (VIF). The variable's greatest VIF value is 2.71 (less than 5.0), which supports the conclusion that the data does not exhibit multicollinearity (Hair et al., 2017).

Path analysis

Reliability and Validity

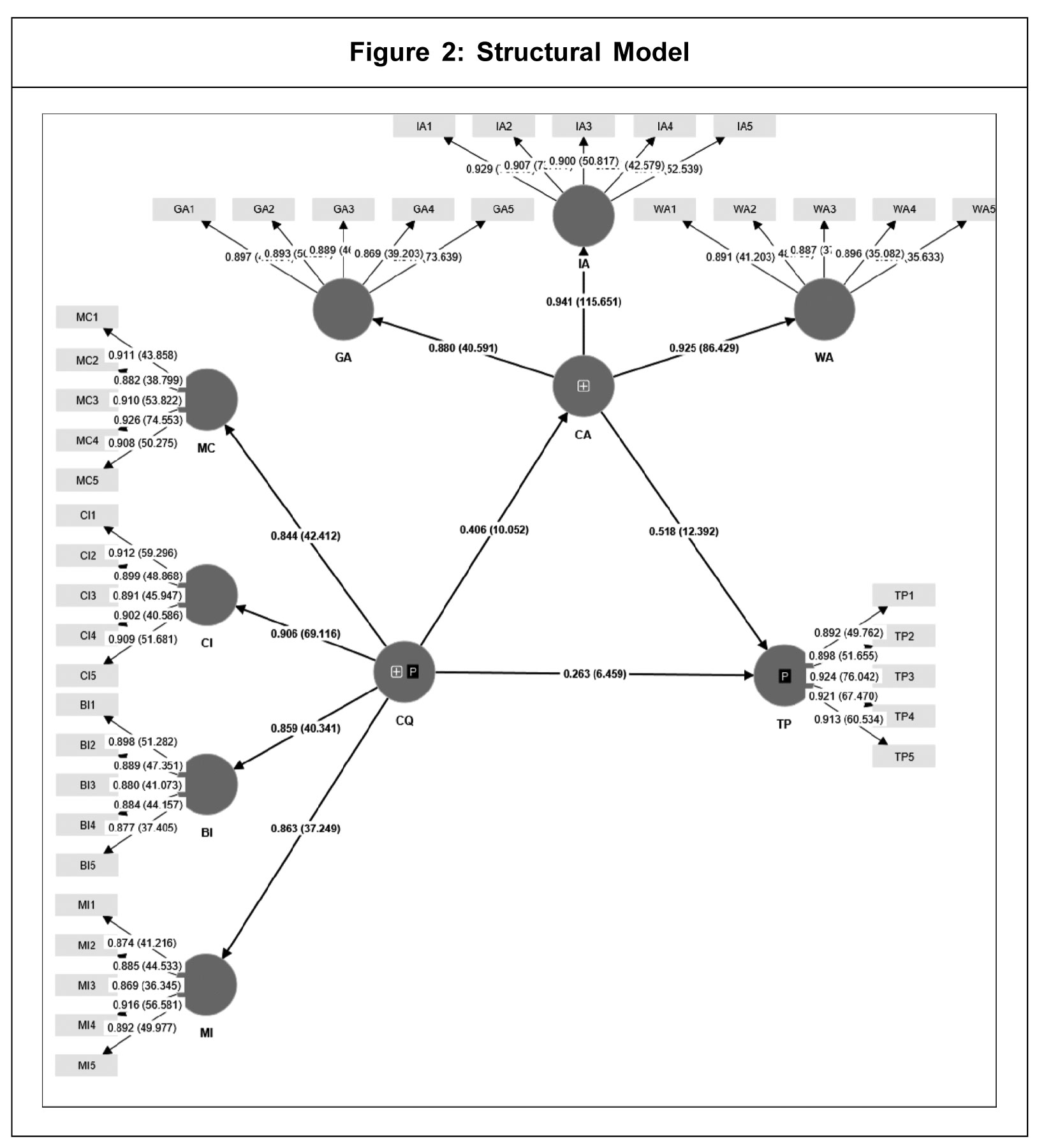

Partial least squares-structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) was used to test the hypothetical relationship described in the conceptual model (Ringle et al., 2022). Both measurement and structural models are produced by PLS-SEM. The structural model was used to test the hypothesis, while the measurement model was used to evaluate the model's validity and reliability. Two second order constructs, referred to as CQ and CA, are included in the conceptual model presented. Wetzels et al. (2009) claimed that all 20 items from the first order constructs of metacognitive, cognitive, motivational, and behavioral intelligence are incorporated in the assessment of the second order construct of CQ, similar to how the PLS-SEM model included all 15 items from first-order constructs, including general, work, and interaction adjustments, to evaluate the second order construct of CA.

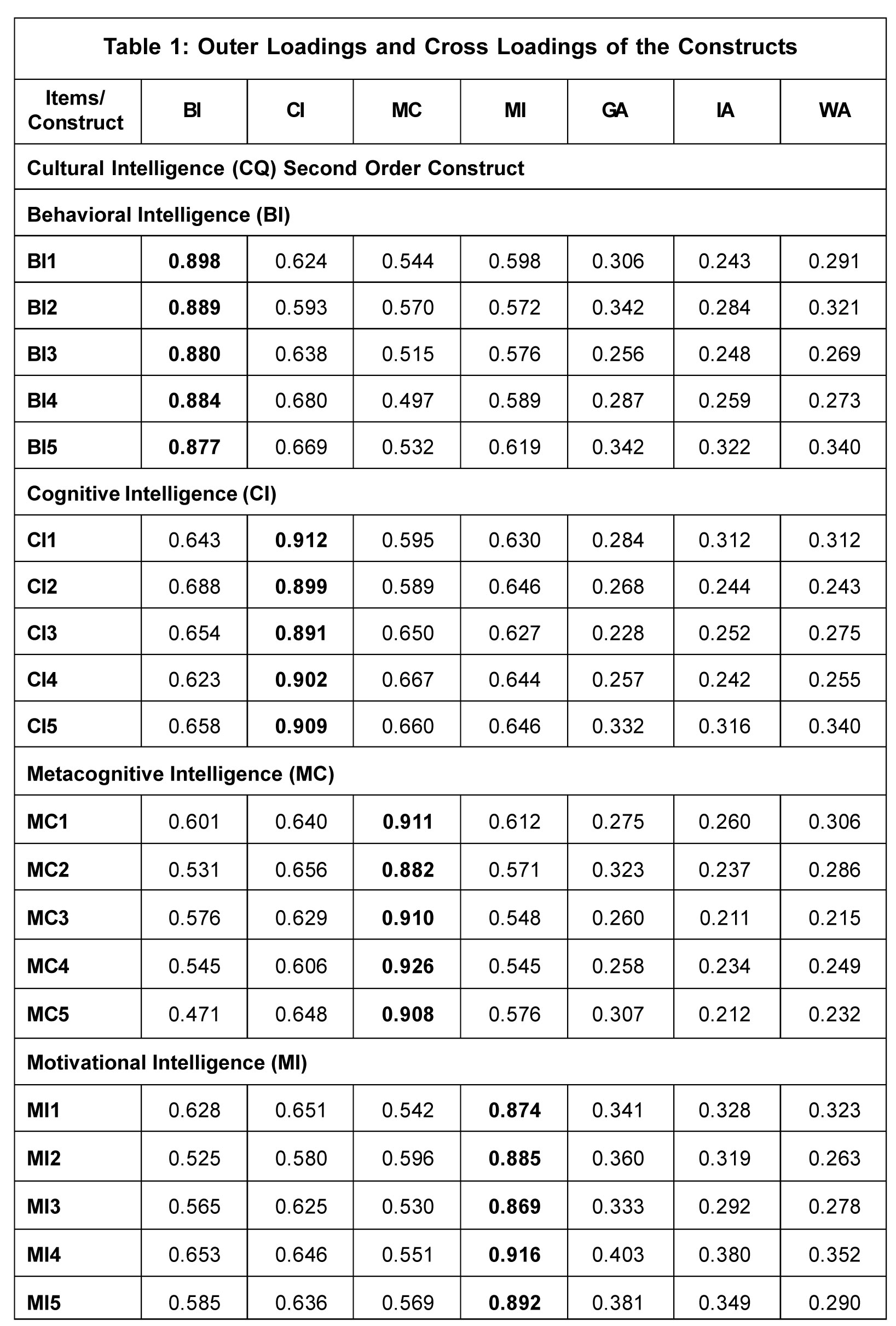

The outer and cross loadings of each item in the first order structures are listed in Table 1. Convergent and discriminant validity were used to evaluate the measurement model's construct validity. The scale's convergent validity was confirmed by computing outer and cross loadings, as indicated by Hair et al. (2017). The cross loadings of all the items were found to be less than their outer loadings, confirming the scales' convergent validity as proposed by Hair et al. (2017). The outer loadings of all the items are all greater than the threshold value of 0.5. The Average Variance Extracted (AVE) value of the constructs was another indicator of the convergent validity of the constructs. The AVE value of each construct utilized in the current investigation exceeded the cutoff value of 0.5, as advised by Hair et al. (2017), establishing the convergent validity of the constructs.

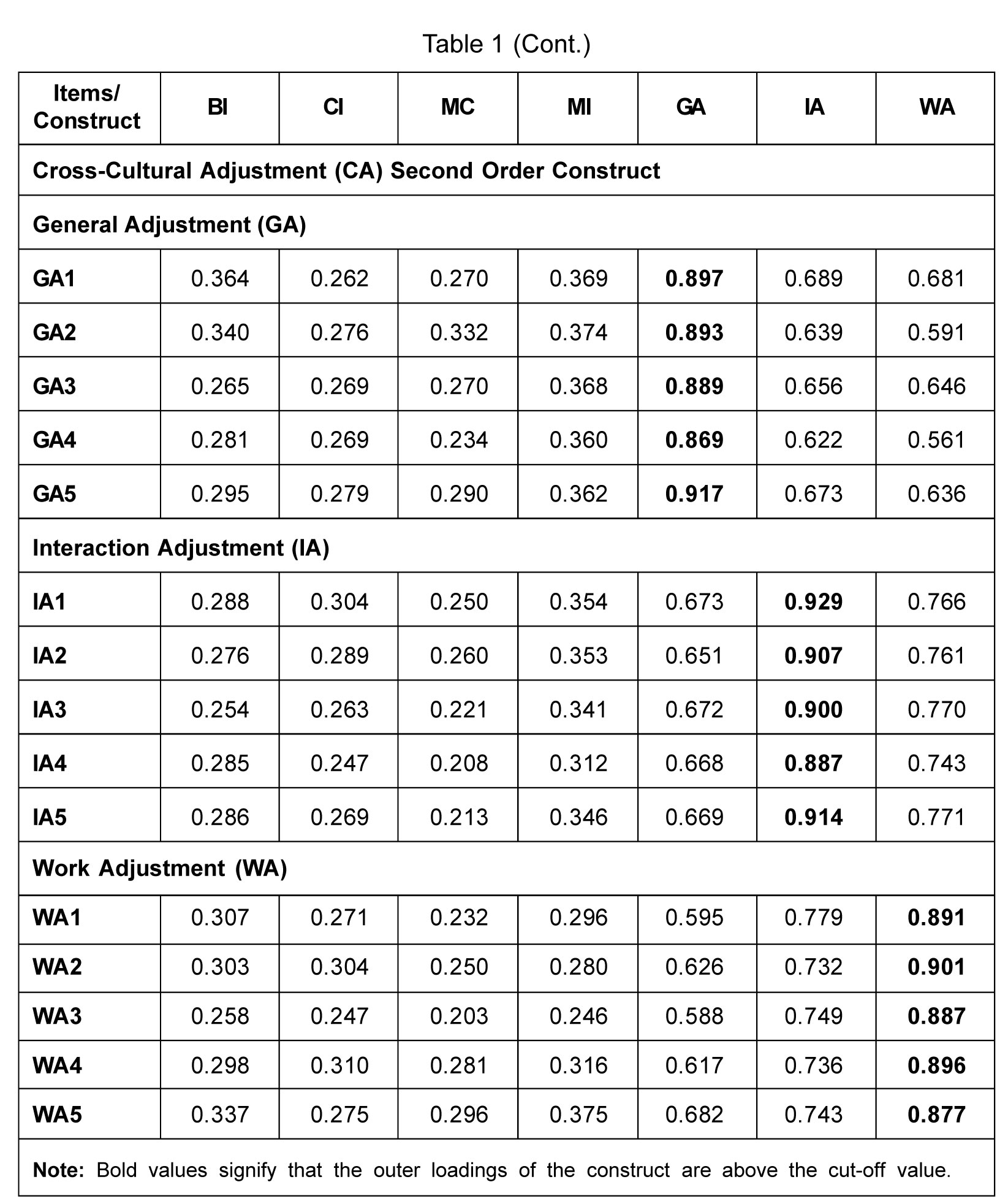

The reliability and validity of the construct are shown in Table 2. According to Fornell and Larcker (1981), all first order constructs (BI = 0.784, CI = 0.815, MC = 0.824,

MI = 0.787, GA = 0.798, IA = 0.823, and WA = 0.793) and second order constructs (CQ = 0.605 and CA = 0.675) have AVE values greater than the cut-off point of 0.5. Additionally, the discriminant validity of the first order constructs employed in the study was examined using the Fornell-Larcker criterion. All of the first order constructs have square root of AVE values that are greater than their corresponding inter-correlations with the other constructs employed in the study.

As per this criterion, the square root of AVEs of the respective construct should be more than that construct's inter-correlations with other constructs under study (Hair

et al., 2017). In Table 2, the results of the square root of AVEs of all the first order constructs are presented in diagonals and in bold, and their respective inter-correlations are also shown. The square root of the AVE values of all the first order constructs was found to be more than their inter-correlations, which satisfactorily confirms the discriminant validity of all the constructs under study.

The constructs' reliability was examined using Cronbach's alpha and composite reliability values. The reliability of the constructs utilized in the study is supported by Cronbach's alpha and composite reliability values that are higher than the cut-off point of 0.70 (Hair et al., 2017). The threshold value of 0.7 for Cronbach's alpha is exceeded by all first order constructs (BI = 0.931, CI = 0.943, MC = 0.947, MI = 0.932, GA = 0.936, IA = 0.946, and WA = 0.935) and second order constructs (CQ = 0.966 and CA = 0.966). The reliability of all the constructs is demonstrated by the fact that all first order constructs (BI = 0.968, CI = 0.957, MC = 0.959, MI = 0.949, GA = 0.936, IA = 0.959, and

WA = 0.950) and second order constructs (CQ = 0.968, and CA = 0.969) are more than the threshold value of 0.7 for Composite reliability. The bootstrapping approach was used to determine the relevance of the factor loadings of first order constructs with their corresponding second order constructs. With the number of cases equal to the sample size of our study (n = 429), we performed the bootstrapping approach with 5,000 samples. Additionally, at p-value 0.01 level, the first order constructs significantly loaded with the corresponding second order constructs.

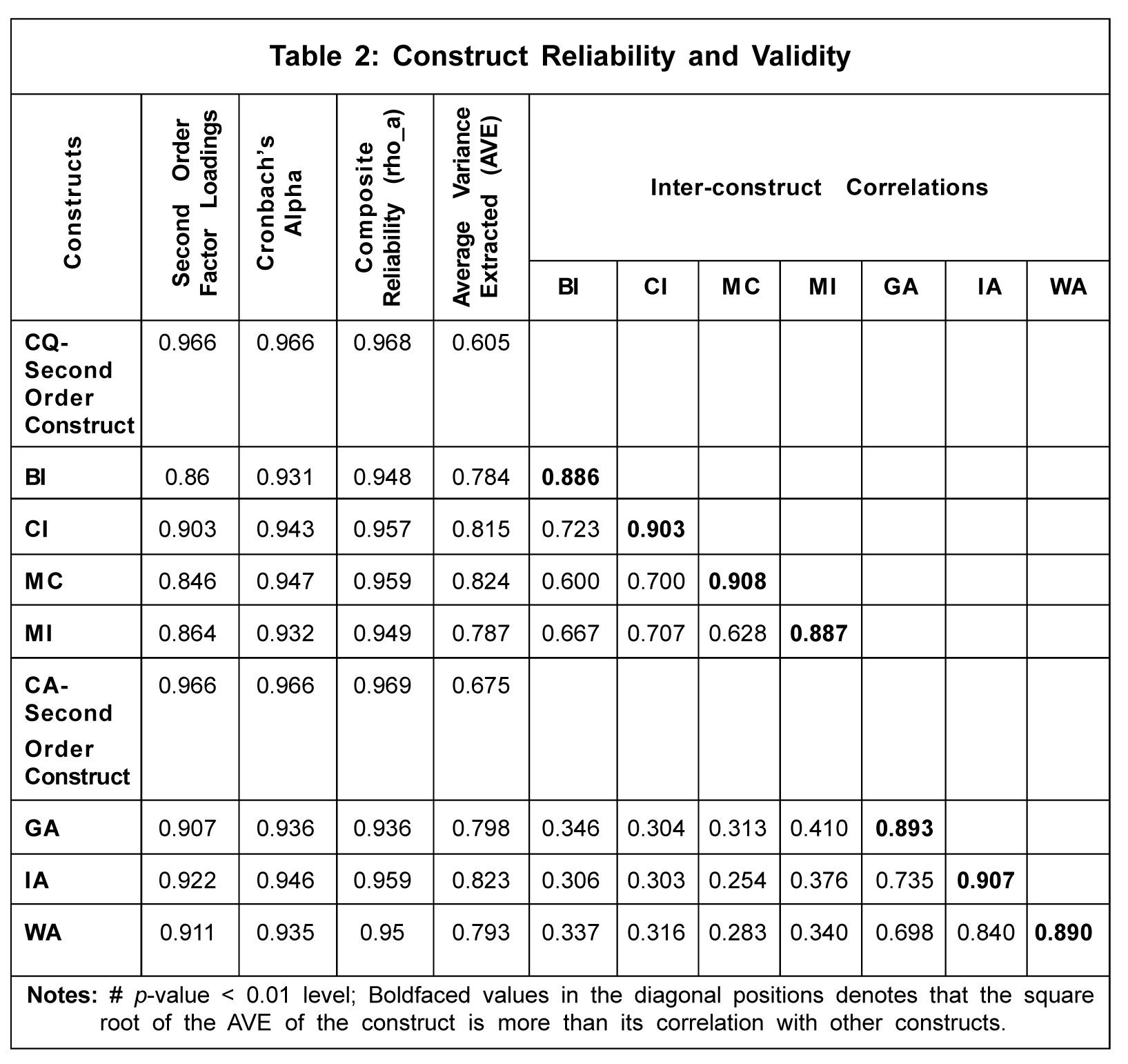

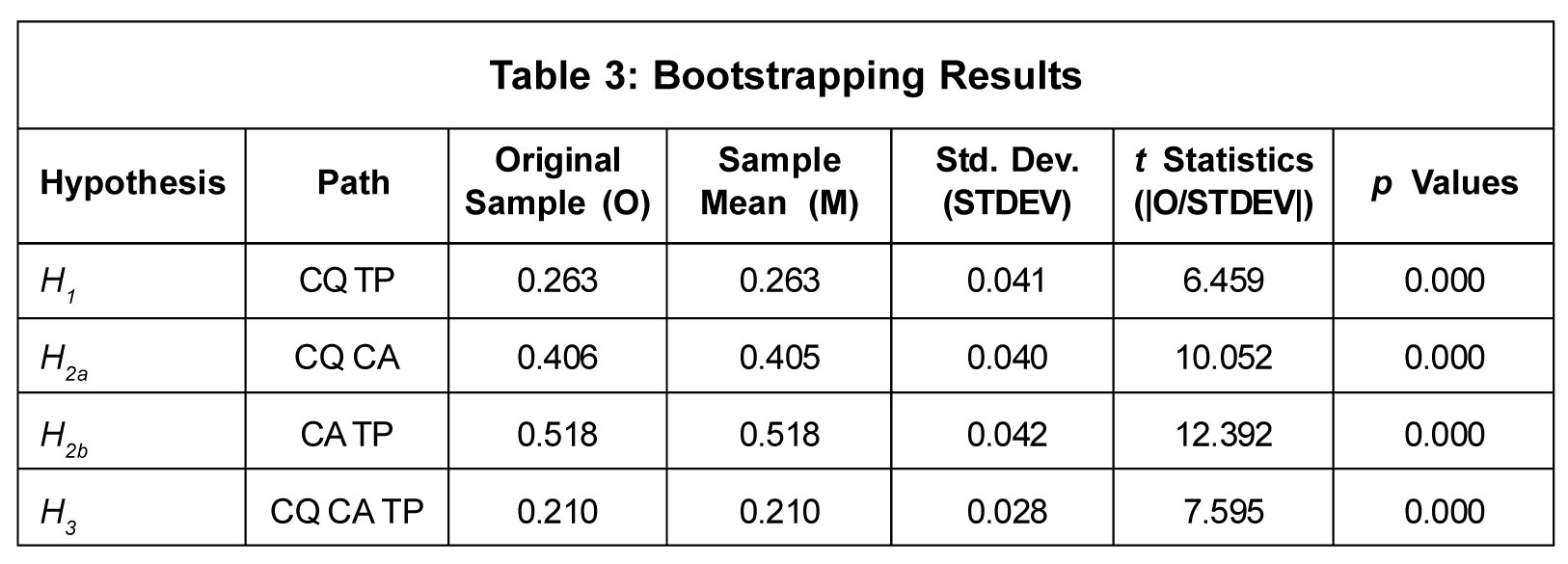

Hypotheses Testing

Table 3 displays the findings of the direct effects and straightforward mediation analyses. All of the fictitious relationships' path coefficients are significant at 1% level. It is clear from the results that CQ has a significant positive (direct) influence on TP (0.263) and CA (0.406). Furthermore, CA strongly influences TP positively (directly) (0.518). The findings of this study make it clear that employees' CQ improves their CA and TP because a better appreciation of the significance of cultural differences at work improves their job performance by enhancing their ability to adjust in cross-cultural teams. In other words, CQ helps people quickly adapt to a new cultural setting and lessens their culture shock, which improves work performance. The cross-cultural adaptability and cultural intelligence

constructs account for 55.2% (or a moderate degree) of the variation in task performance. Through the partial mediation of CA, CQ has a statistically significant positive indirect effect on TP (0.210) that is significant at 1% level. The direct positive link between CQ and TP is shown in hypothesis H1 (b = 0.263, t = 6.459, p = 0.001), and this direct relationship is partially mediated by CA (b = 0.210, t = 7.595, p = 0.001) at 1% significance level.

The structural model of the study is given in Figure 2.

Implications

The study contributes to the prevailing literature by elucidating the underlying mechanisms that connect cultural intelligence, cross-cultural adjustment, and task performance in the IT industry context in India. By establishing cross-cultural adjustment as a significant mediator, this study advances our understanding of how cultural intelligence translates into improved task performance. The study also improves the understanding of CQ as

an operative intercultural competency construct by providing an association among CQ, cultural adjustment and task performance. It also advances the theoretical developments of Earley and Ang's (2003) CQ concept. Finally, this paper delivers an integrative framework for the study of the association between CQ and TP with mediating role of CA in the Indian context.

The investigation into the mediating role of cross-cultural adjustment between cultural intelligence and task performance holds significant theoretical implications, enriching our understanding of individual behavior, adaptation, and performance in multicultural context. This study contributes to various theoretical frameworks and offers novel perspectives on the mechanisms through which these constructs interact.

This study bridges the gap between different dimensions of individual competence by examining the interplay among cultural intelligence, cross-cultural adjustment, and task performance. The theoretical inferences lie in the integration of these multidimensional constructs within a coherent framework. It underscores that cultural intelligence acts as a precursor to effective cross-cultural adjustment, which in turn, enhances task performance. This integration enhances our comprehension of how individual characteristics intersect with adaptive processes to influence tangible outcomes in diverse work environments.

The theoretical implications extend to the cognitive and behavioral mechanisms that underlie the relationships among cultural intelligence, cross-cultural adjustment, and task performance. By identifying cross-cultural adjustment as a mediating factor, this study unveils the cognitive processes through which individuals with higher cultural intelligence engage in adaptive behaviors that facilitate successful integration into new cultural contexts. This contributes to theories of cognitive adaptation and behavioral change in response to cross-cultural challenges.

The theoretical implications extend to the contextual nature of cultural intelligence. This study emphasizes that the effects of cultural intelligence on task performance are channeled through the lens of successful cross-cultural adjustment. This contextualization of cultural intelligence highlights the necessity for considering the dynamic interaction between individual traits and the challenges of adapting to new cultural contexts.

The findings of the study have several crucial inferences for managers and organizations seeking to optimize performance in diverse and globalized work environments. Understanding the mediating role of cross-cultural adjustment in the association between cultural intelligence and task performance offers actionable insights for talent development, employee support, and strategic decision-making.

IT companies should incorporate cultural intelligence as a desirable trait when recruiting new employees, especially for positions that involve cross-cultural interactions in project teams. Assessing candidates' cultural intelligence during the hiring process can help ensure that individuals with the aptitude to adapt and excel in diverse settings are chosen. This proactive approach can lead to quicker integration, reduced turnover, and enhanced task performance.

Cultural intelligence can be enhanced and developed via training, experience, and life events; it is not static. Through cross-cultural team building, mentoring and buddy systems, diversity and inclusion training, cultural competency workshops, and other methods, IT businesses can cultivate cultural intelligence in IT firms. Cultivating CQ is crucial, particularly in the diverse and multinational work settings of today. Increasing cultural intelligence among IT teams can boost overall efficacy, creativity, and teamwork.

Further, investing in training programs aimed at enhancing cultural intelligence and cross-cultural adjustment can yield substantial benefits. These programs can equip employees with the skills and knowledge needed to navigate cultural differences effectively. Furthermore, offering guidance on coping strategies, communication techniques, and problem-solving in cross-cultural contexts can foster a sense of confidence and competence, leading to improved overall task performance.

Managers of IT organizations should recognize the importance of cross-cultural adjustment as a mediating factor for translating cultural intelligence into task performance. When evaluating employee performance, it is essential to consider not only their cultural intelligence but also their capability to familiarize to fresh cultural environment. By setting performance goals that encompass both dimensions, managers can ensure that employees' capabilities are effectively leveraged and that their contributions are aligned with the organization's global objectives.

IT organizations can use the insights from this study to enhance their diversity and inclusion strategies. By fostering a welcoming and inclusive environment, organizations can help reduce the stress and barriers associated with cross-cultural adjustment. When employees feel appreciated and supported, they are more likely to engage in effective adjustment strategies, leading to higher levels of task performance.

In sum, recognizing the mediating role of cross-cultural adjustment in the association between cultural intelligence and task performance offers actionable insights for managers and organizations. By incorporating these insights into recruitment, training, performance management, and diversity strategies, organizations can create an environment that fosters effective cross-cultural adjustment and leverage cultural intelligence to drive enhanced task performance. As the global workforce continues to diversify, embracing these implications can lead to competitive advantages and sustained success in today's interconnected world.

Conclusion

This study delved into the intricate interplay among cultural intelligence, cross-cultural adjustment, and task performance, aiming to shed light on the mediating role of cross-cultural adjustment in the association among these constructs. The conclusion of this study delivers valuable vision into the mechanisms underlying the linkages between cultural intelligence and task performance, while highlighting the crucial role of effective cross-cultural adjustment as a mediating factor.

The first aim of the study was to scrutinize the association between cultural intelligence and task performance. The results of the analysis indicate a noteworthy positive association between these two constructs. So the conclusion is in agreement with previous studies, underscoring the notion that individuals with higher cultural intelligence possess a heightened ability to navigate and thrive in culturally diverse environment, subsequently enhancing their overall task performance. This implies that organizations and individuals alike should invest in enhancing cultural intelligence as a means of improving job-related outcomes.

The second objective of the study was to explore the role of cross-cultural adjustment as a mediator between cultural intelligence and task performance. The results provide strong support for the mediating role of cross-cultural adjustment. Specifically, the results indicate that persons with higher cultural intelligence are more likely to participate in effective cross-cultural adjustment, which in turn leads to improved task performance. This underscores the importance of not only possessing cultural intelligence but also effectively applying it through successful adjustment strategies in order to optimize performance outcomes.

The study underscores the significance of cultural intelligence as a predictor of task performance, and it further highlights the role of cross-cultural adjustment as a mediator in this relationship. By elucidating the mechanisms that underlie these connections, this study delivers an appreciated understanding of both theoretical advancement and practical application. As organizations continue to operate in culturally diverse environment, understanding and leveraging the interplay between these constructs can pave the way for improved performance outcomes and overall success.

Limitations and Future Scope: The results of the study have certain limitations. Firstly, the study's cross-sectional design limits our capability to draw causal inferences, and longitudinal research could provide deeper insights into the temporal dynamics of these relationships. Additionally, the study relied on self-report measures, which can introduce common method bias and potential inaccuracies. Future research could benefit from utilizing multi-source and multi-method approaches to mitigate this concern. Moreover, the study is piloted within a particular organizational background, which might restrict the generalizability of the outcomes to other settings.

Hence, the study has focused only on one result of cultural intelligence, i.e., task performance. In the future, more results can be focused on, such as the effectiveness of leadership and culture, organizational commitment, etc., for an improved understanding of the CQ theory. Next, the study has not examined any antecedents of cultural intelligence such as social intelligence, personality traits, emotional intelligence, etc., therefore, future research can be carried out by taking up these antecedents.

References

- Ang S, Van Dyne L, Koh C et al. (2007), "Cultural Intelligence: Its Measurement and Effects on Cultural Judgment and Decision-Making, Cultural Adaptation and Task Performance", Management and Organization Review, Vol. 3, No. 3, pp. 335-371.

- Ang S and Van Dyne L (2008), Handbook on Cultural Intelligence: Theory, Measurement and Applications, M.E. Sharpe, Armonk, NY.

- Banerjee A (2013), "What's Indian Culture? A Dive into Domestic Diversity", http://davidlivermore.com/2013/08/16/whats-indian-culture-a-dive-into-domestic-diversity/. Accessed on July 15, 2023.

- Baron R M and Kenny D A (1986), "The Moderator-Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research: Conceptual, Strategic and Statistical Considerations", Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 51, No. 6, pp. 1173-1182.

- Bess T (2001), "Exploring the Dimensionality of Situational Judgment: Task and Contextual Knowledge", a Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Science in Psychology.

- Bhaskar-Shrinivas P, Harrison D A, Shaffer M A and Luk D M (2005), "Input-Based and Time[1]-Based Models of International Adjustment: Meta-Analytic Evidence and Theoretical Extensions", Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 48, No. 2, pp. 259-281.

- Black J S and Porter L W (1991), "Managerial Behavior and Job Performance: A Successful Manager in Los Angeles May Not Be Successful in Hong Kong", Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 22, No. 1, pp. 99-114.

- Black J S and Stephens G K (1989), "The Influence of the Spouse on American Expatriate Adjustment and Intent to Stay in Pacific Rim Overseas Assignments", Journal of Management, Vol. 15, No. 4, pp. 529-544.

- Caligiuri P M (1997), "Assessing Expatriate Success: Beyond Just Being There", in D M Saunders and Z Aycan (Eds), New Approach Employee Management, Vol. 4, pp. 117-140.

- Campbell M C (1999), "Perceptions of Price Unfairness: Antecedents and Consequences", Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 36, No. 2, pp. 187-199. https://doi.org/10.2307/3152092

- Chen X P, Liu D and Portnoy R (2012), "A Multilevel Investigation of Motivational Cultural Intelligence, Organizational Diversity Climate and Cultural Sales: Evidence from US Real Estate Firms", Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 97, No. 1, pp. 93-106.

- Christine K, Damien J and Soon A (2009), "Cultural Intelligence and the Global Information Technology Workforce", IWIC '09: Proceedings of the 2009 International Workshop on Intercultural Collaboration, pp. 261-264. https://doi.org/10.1145/1499224.1499271

- Demes K and Geeraert N (2014), "Measures Matter: Scales for Adaptation, Cultural Distance and Acculturation Orientation Revisited", Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, Vol. 45, No. 1, pp. 91-109. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022113487590.

- Earley P C and Ang S (2003), Cultural Intelligence: Individual Interactions Across Cultures, Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA.

- Earley P C and Peterson R S (2004), "The Elusive Cultural Chameleon: Cultural Intelligence as a New Approach to Intercultural Training for the Global Manager", Academy of Management Learning and Education, Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 100-115.

- Fornell C G and Larcker D F (1981), "Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error", Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 18, No. 1, pp. 39-50.

- Gardner H (1983), Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences, Basic Books, New York.

- Gregersen H B and Black J S (1990), "A Multifaceted Approach to Expatriate Retention in International Assignments", Group Organization Studies, Vol. 15, No. 4, pp. 461-485.

- Hair J F, Hult GT, Ringle C M et al. (2017), A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd Edition, Sage Publications, Inc., Los Angeles.

- Huff K C, Song P and Gresch E B (2014), "Cultural Intelligence, Personality, and Cross-Cultural Adjustment: A Study of Expatriates in Japan", International Journal of Intercultural Relations, Vol. 38, No. 1, pp. 151-157.

- IBEF (2023), "IT & BPM Industry in India". https://www.ibef.org/industry/information-technology-india

- Jyoti J and Kour S (2015), "Assessing the Cultural Intelligence and Task Performance Equation: Mediating Role of Cultural Adjustment", Cross Cultural Management: An International Journal, Vol. 22, No. 2, pp. 236-258. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCM-04-2013-0072

- Jyoti J and Kour S (2017a), "Cultural Intelligence and Job Performance: An Empirical Investigation of Moderating and Mediating Variables", International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, Vol. 17, No. 3, pp. 305-326.

- Jyoti J and Kour S (2017b), "Factors Affecting Cultural Intelligence and Its Impact on Job Performance Role of Cross-Cultural Adjustment, Experience and Perceived Social Support", Personnel Review, Vol. 46, No. 4, pp. 767-791.

- Kim K and Slocum J W (2008), "Individual Differences and Expatriate Assignment Effectiveness: The Case of US-Based Korean Expatriates", Journal of World Business, Vol. 43, No. 1, pp. 109-126.

- Kock N (2015), "Common Method Bias in PLS-SEM: A Full Collinearity Assessment Approach", International Journal of e-Collaboration, Vol. 11, No. 4, pp. 1-10.

- Kodwani A D (2012), "Beyond Emotional Intelligence (EQ): The Role of Cultural Intelligence (CQ) on Cross-Border Assignments", World Review of Business Research, Vol. 2, No. 4, pp. 86-102.

- Kour S and Jyoti J (2022), "Cross-Cultural Training and Adjustment Through the Lens of Cultural Intelligence and Type of Expatriates", Employee Relations, Vol. 44, No. 1, pp. 1-36. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-07-2020-0355

- Kumar N, Rose R C and Subramaniam R (2008), "The Effects of Personality and Cultural Intelligence on International Assignment Effectiveness: A Review", Journal of Social Science, Vol. 4, No. 4, pp. 320-328.

- Lee L Y and Sukoco B M (2010), "The Effects of Cultural Intelligence on Expatriate Performance: The Moderating Effects of International Experience", The International Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 21, No. 7, pp. 963-981.

- Lee L Y and Kartika N (2014), "The Influence of Individual, Family, and Social Capital Factors on Expatriate Adjustment and Performance: The Moderating Effect of Psychology Contract and Organizational Support", Expert Systems with Applications, Vol. 41, No. 11, pp. 5483-5494.

- Motowidlo S J, Borman W C and Schmidt M J (1997), "A Theory of Individual Differences in Task and Contextual Performance", Human Performance, Vol. 10, No. 2, pp. 71-83.

- Ng K Y, Van D L and Ang S (2012), "Cultural Intelligence: A Review, Reflections, and Recommendations for Future Research", in A M Ryan, F vT Leong and F L Oswald (Eds.), Conducting Multinational Research: Applying Organizational Psychology in the Workplace, pp. 29-58, American Psychological Association, Washington, DC.

- Podsakoff P M, MacKenzie S B, Lee J Y and Podsakoff N P (2003), "Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies", Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 88, No. 5, pp. 879-903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Presbitero A and Toledano L S (2018), "Global Team Members' Performance and the Roles of Cross-Cultural Training, Cultural Intelligence, and Contact Intensity: The Case of Global Teams in IT Offshoring Sector", International Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 29, No. 14, pp. 2188-2208. doi:10.1080/09585192.2017. 1322118.

- Ramalu S, Rose R C, Kumar N and Uli J (2010), "Doing Business in Global Arena: An Examination of the Relationship Between Cultural Intelligence and Cross-Cultural Adjustment", Asian Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 15, No. 1, pp. 79-97.

- Ramalu S, Rose R C, Kumar N and Uli J (2012), "Cultural Intelligence and Expatriate Performance in Global Assignment: The Mediating Role of Adjustment", International Journal of Business and Society, Vol. 13, No. 1, pp. 19-32.

- Ramalu S S, Wei C C and Rose R (2011), "The Effect of Cultural Intelligence on Cross-Cultural Adjustment and Job Performance Amongst Expatriates in Malaysia", International Journal of Business and Social Science, Vol. 2, No. 9, pp. 59-71.

- Ringle C M, Wende S and Becker J M (2022), "SmartPLS 4", Oststeinbek: SmartPLS GmbH, http://www.smartpls.com. Accessed on July 10, 2023.

- Shaffer M A, Harrison D A, Gregersen H, Black J S and Ferzandi L A (2006), "You Can Take It with You: Individual Differences and Expatriate Effectiveness", Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 109-125.

- Sternberg R. J and Detterman D K (1986), What Is Intelligence? Contemporary Viewpoints on Its Nature and Definition, Ablex Publishing Corporation, New York City, New York.

- Stone-Romero E, Stone D L and Salas E (2003), "The Influence of Culture on Role Conceptions and Role Behavior in Organizations", Applied Psychology: An International Review, Vol. 52, No. 3, pp. 328-362.

- Wang M and Takeuchi R (2007), "The Role of Goal Orientation During Expatriation: A Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Investigation", Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 93, No. 5, pp. 1437-1445.

- Wetzels M, Odekerken-Schroder G and Van Oppen C (2009), "Using PLS Path Modeling for Assessing Hierarchical Construct Models: Guidelines and Empirical Illustration", Management Information Systems, Vol. 33, No. 1, pp. 177-95.