October'23

The IUP Journal of Organizational Behavior

Archives

Perception of Fit and Workplace Fun as Drivers of Employee Engagement

Antriksha Negi

Assistant Professor, Department of Commerce, Laxman Singh Mahar (L.S.M) Government Post Graduate

College Pithoragarh, Uttarakhand, India; and is the corresponding author. E-mail: antriksha.ignou@gmail.com

Ravinder Pant

Assistant Professor, Department of Commerce, Atma Ram Sanatan Dharma College (ARSD), University of

Delhi, New Delhi, India. E-mail: rpantscholar@gmail.com

Nawal Kishor

Professor, School of Management Studies (SOMS), Indira Gandhi National Open University (IGNOU),

New Delhi, India. E-mail: nkishor@ignou.ac.in

During the Covid-19 pandemic, employees had to cope with a practically changed working scenario, especially work-from-home. Two major challenges faced by the companies were: to ensure the availability of important tools and gadgets to their staff for performing their jobs from home; and to ensure that the employees are engaged in their jobs effectively. The study sample comprised 276 employees of various service sector organizations operational in Delhi NCR. Using a descriptive and cross-sectional research design, multiple regression analysis and correlations, the study found that employee engagement is highly driven by workplace fun and perception of fit shown by the employees, which lead to organizational productivity and efficiency.

Introduction

Globally, the labor market was highly disrupted by the Covid-19 pandemic, with millions of people losing their jobs and others having to adjust to the new emerging mode of performing their job from home as offices were shut down to follow the World Health Organization (WHO) Covid-19 guidelines. During the pandemic, employees had to cope with a practically changed working scenario, especially work from home. Companies were rapidly pushed by the pandemic to adopt new work norms (Lund et al., 2021). In order to ensure business continuity, organizations were forced to embrace remote working, i.e., Work From Home (WFH) (Aitken-Fox et al., 2020). MNCs like Amazon, Microsoft, Facebook, Google, Deloitte, etc. announced in 2020 that they would shut their offices and shift their entire staff to the WFH framework (MoneycontrolNews, 2020) or allow their employees to work remotely up to half of their weekly working hours (Reuters, 2020). With the remote working environment, the companies faced major challenges related to various aspects such as ensuring the availability of important tools and gadgets to their staff for performing their jobs from home, and ensuring that the employees are engaged in their jobs effectively (Aitken-Fox et al., 2020).

Literature Review

The organizations need to have highly engaged, dedicated and energetic workforce since human resources are the most important component of any organization's success; especially during the pandemic. The concept of engagement is difficult to define in exact terms. Using data from secondary sources, the EFFECTS model was proposed by Negi et al. (2021), which states that employee voice, workplace fun, feelings of employees, emotional support, compassion, training and development and supervision are important for any employee to be engaged. An engaged employee performs his/her job efficiently by being emotionally, cognitively, and physically involved in the job (Rich et al., 2010). Employee engagement is also defined as the intellectual and emotional commitment of an employee towards the organization or the extent to which employees exhibit discretionary efforts towards their job (Frank et al., 2004). Work engagement and organizational engagement were differentiated clearly by Saks (2006) as he referred to employee engagement as a unique construct comprising emotional, behavioral and cognitive concepts related to the role performance of an individual. The concept of engagement is also impacted by various demographic dimensions such as family type and marital status (Negi et al., 2022). Studies in the past suggested that employee engagement can be fostered by organizations by creating a resourceful yet challenging environment to work (Rich et al., 2010).

Employee Engagement: Exploring New Dimensions

During the Covid-19 phase, meaningful work experience played a critical role in employee engagement, turnover intention and performance appraisal. The role of meaningful work and employee engagement has become rather critical for organizations to understand employee's intention to leave the organization and to maintain a healthy relationship. Meaningful work is characterized by perception of fit by an employee towards the job and towards the organization. Person-job fit is referred to as the compatibility of employee's traits and characteristics with their job demands (Kristof, 1996; and Cable and DeRue, 2002). Person-Environment fit theory posits that individuals are likely to be attracted to and shortlisted by such organizations whose working environment reflects the same cultural values and beliefs of the individuals (Kristof, 1996).

Workplace fun is also a key component of organizational success, at least in the last few decades. In the book, Built to Last by Collins and Porras (1997), mention how Walt Disney World and Marriott have a strong corporate culture that emphasizes workplace fun to a large extent. Another example of a company incorporating workplace fun is Google, the organization known for providing a positive workplace; it believes that fun comes from everywhere, therefore it has incorporated fun in organizational setting as well (Schmidt and Rosenberg, 2014). Workplace fun helps to promote cohesive workplace relationships, engagement, creativity and improved employee's physical and mental wellbeing (Vorhauser-Smith, 2013). Workplace fun leads to employee companionship and improved trust and motivation among employees (Caccamese, 2012). Nicastro (2020) emphasized the importance of communication, trust and relationship building to employee engagement. Digital gifts, beverages, plants, treats, etc. are some of the means to create a fun environment and have better connectivity, thereby leading to better engagement of employees. The bond between employees should be strengthened by virtual fun events, lunches, etc. With WFH, personal touch and meetings seem to be missing. Therefore, scheduling calls with team members regularly will help employees to get motivated and feel associated with the organization (Dhingra and Agarwal, 2020).

Previous studies have drawn various conclusions regarding the role and relevance of perception of fit and workplace fun. Overall these two components seem to contribute favorably to employee engagement. Yet, the limited studies available in the Indian context justifies the rationale for the current study. The study aims to explore whether perception of fit and workplace fun have any correlation with employee engagement in Indian services sector companies. The relationship between employee engagement and perception of fit and workplace fun has relevance for the post-pandemic world too (Negi et al., 2023). The rapid pace of technological innovation, expanding subtleties of business management, pressure to become a world-class organization, and relative paucity of employees with relevant skills have all contributed to challenges associated with attracting, sustaining, and leveraging talent in most organizations around the world.

Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Formulation

Workplace Fun and Employee Engagement

Workplace fun is referred to as work environment which intentionally helps to initiate, encourage and support a variety of pleasurable and enjoyable activities (Ford et al., 2003). It involves activities that are not essentially related to the job but are enjoyable, playful and amusing to the participants (McDowell, 2005). Workplace fun comprises activities that are personally meaningful and enjoyable and are a good fit for individuals (Tews

et al., 2014). Workplace fun reflects social activities such as outings, team-building exercises, and publicly celebrating employees' achievements and milestones in order to bring a sense of commitment and enjoyment (Karl et al., 2005). Researchers in recent years have started to pay more attention to the role and importance of workplace fun (Owler et al., 2010; Becker and Tews, 2016; and Plester and Ann, 2016). Deal and Kennedy (1999) stated that the fun quotient of the organization will help the employees to put their heart and soul into what they do; hence considering this, workplace fun should lead to work engagement. Workplace fun includes parties, social gatherings, group competition, awards and recognition and the participation of employees in informal workplace fun in the organization (Karl and Peluchette, 2005). A few empirical studies have scrutinized the effect of workplace fun (Karl et al., 2005). Although no studies have examined the direct relationship between work engagement and workplace fun, there exist two theoretical explanations: it acts as a job resource and functions as a recovery mechanism that influences the level of engagement of the employees. Across populations, both these explanations are found to be intensifying employee engagement (Demerouti et al., 2001; and Sonnentag, 2003). Based on the abovementioned studies, we propose the following hypotheses:

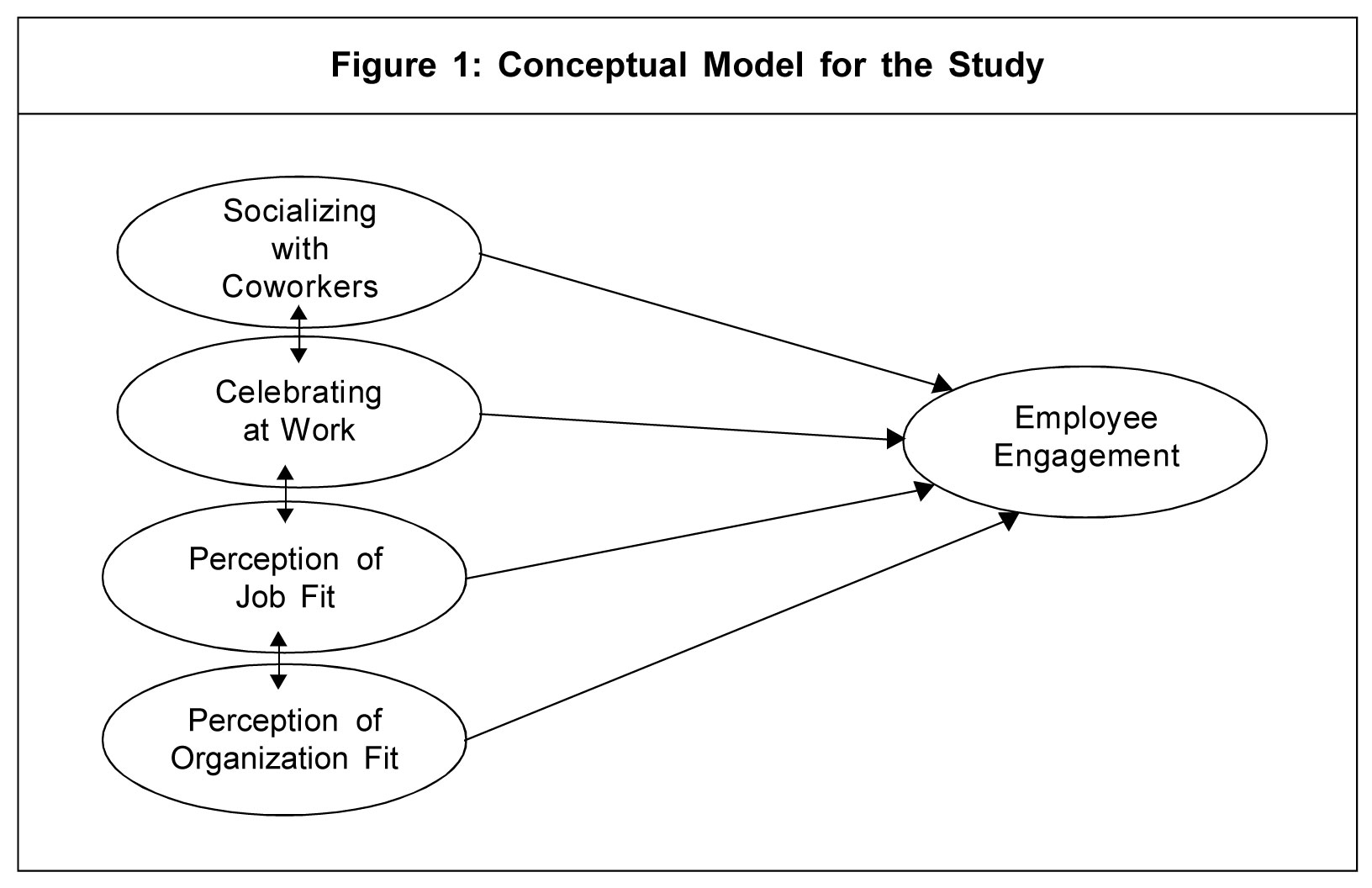

- H1: Socializing with Coworkers (SWC) is positively related to employee engagement.

- H2: Celebrating at Work (CAW) is positively related to employee engagement.

Perception of Job Fit and Employee Engagement

An employee's psychological condition with respect to his job plays a noteworthy role in employee engagement (May et al., 2004; and Juhdi et al., 2013). Person-job fit is referred to as a correlation between the characteristics of a job and those of an employee (Kristof-Brown et al., 2005). According to Lewin (1951), the more comfortable the worker is with his job, the more effectively he is likely to perform his job and will be guided to achieve the organization's vision and mission dedicatedly (Hussain et al., 2018). Person-job fit is also characterized by the complementary fit, i.e., the link between the abilities of an employee and the job demands, and the needs and desires of an individual and what exactly is provided by the job (Edwards, 1991; and Lauver and Kristof-Brown, 2001). Fit requirements, complementary to each other, are achieved through need fulfillment, supply, and demands by an organization or individual. On the other hand, employees who discover both a realistic indirect and a perceived/direct similarity in values between the organization and the person, experience supplemental fit. (Kristof, 1996; and Cable and DeRue, 2002).

Scroggins (2008) conceptualized the relationship between perception of job fit and engagement using the meaningful work and self-concept of job fit. Job fit is likely to be associated with lower engagement level (Warr and Inceoglu, 2012). Furthermore, empirical evidence supports that there exists a positive association between perception of job fit and job engagement (Lascbinger and Wong, 2006). With reference to North American education sector, Maslach and Leiter (2008) found evidence that perceived congruity between the job and the employees is positively correlated with job engagement. Shuck et al. (2011) also found the impact of job fit on employee engagement. Thus, a positive relationship exists between perception of job fit and employee engagement. Based on the abovementioned studies and arguments, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3: Perception of Job Fit (PoJF) is positively related to employee engagement.

Perception of Organization Fit and Employee Engagement

Greater empowerment to the employees is provided to help them take decisions and discharge duties effectively (Biswas and Varma, 2007). However, employees are likely to utilize the autonomy related to their roles and responsibilities only if they perceive a degree of fit between the employer/organization and themselves (Arthur et al., 2006). Consequently, it was found that employees who display a positive attitude and effect are involved and associated with their jobs and organization as a whole and look forward to contributing in their job and other assignments delegated by the organization (Kahn, 1996). The employees who perceive the organizational environment as comprising of values similar to their own are likely to flourish in the organization and will experience high level of job satisfaction and overall wellbeing, and hence are likely to have more engagement (Kristof-Brown et al., 2005). The literature suggests that strong person- organization fit plays an important role in employee behavior in terms of organizational commitment, job performance and organizational identification (Lauver and Kristof-Brown, 2001; Meyer and Herscovitch, 2001; and Vuuren et al., 2007).

Person-organization fit indicates the manner in which a sense of community is developed within the employee related to the organization's vision, mission and purpose and their own. Person- organization fit is considered an alignment between organizational and individual values and norms. The previous studies reported positive attitude outcome, increased individual commitment, reduced anxiety and increased involvement and organizational activity if there existed person-organization fit (O'Reilly et al., 1991; and Vuuren et al., 2007). Further, when the employees consider themselves fit for the organization, they are assigned greater responsibilities and get a sense of more empowerment. Person-organization fit develops a sense of commonality among the employees towards the employers (Vuuren et al., 2007) and hence increased level of effectiveness in role performance, which leads to psychological security and safety (Biswas and Bhatnagar, 2013). Studies on person-organization fit and organizational engagement and work engagement reveal that the individual develops a tendency to work hard for organizations in which they find values similar to their own (Parkers et al., 2001; and Schneider, 2001). Based on the abovementioned studies, the following hypothesis is formulated:

- H4: Perception of Organization Fit (PoOF) is positively related to employee engagement.

Objective

The study aims to examine the interrelationship between employee engagement and workplace fun and perception of fit:

- Investigate the impact of socializing with coworkers on employee engagement;

- Examine the impact of celebrating at work on employee engagement;

- Identify the influence of perception of job fit on employee engagement; and

- Explore the influence of perception of organization fit on employee engagement.

Data and Methodology

Using descriptive research design, both quantitative and qualitative approaches are selected for the study. A cross-sectional and non-experimental approach is adopted, in which there is no intervention from the researchers and which is based on measurements only.

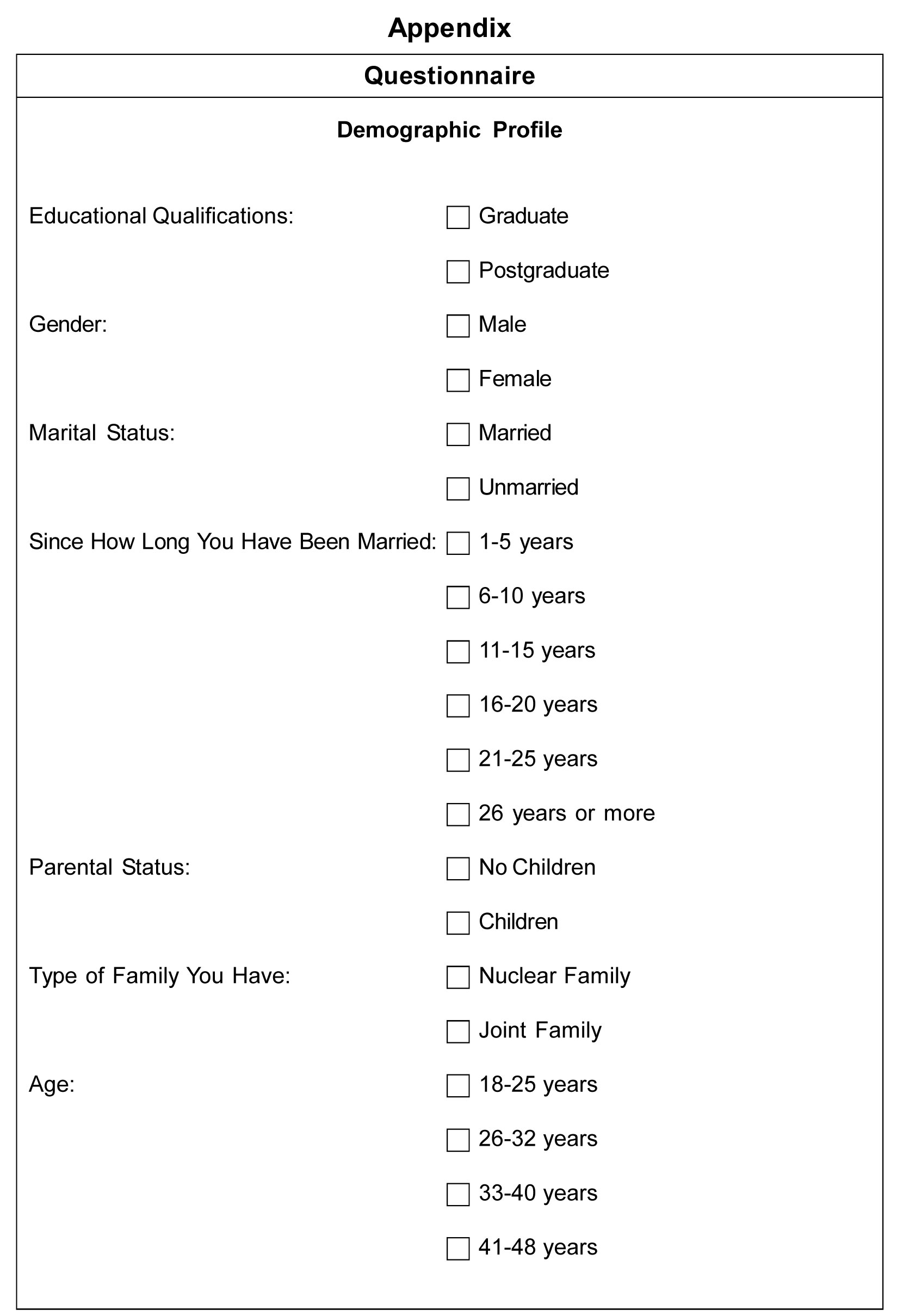

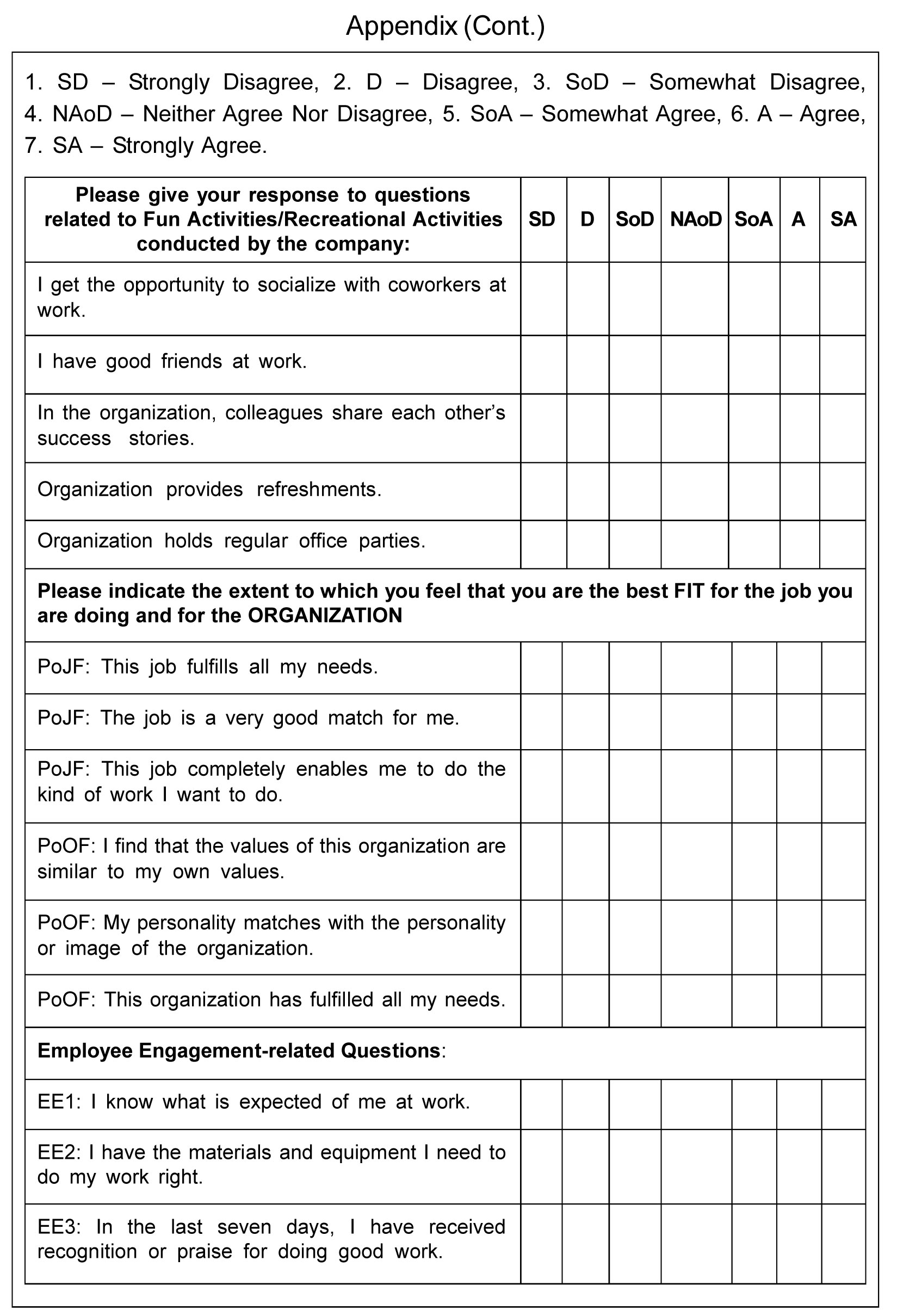

The sample for this study comprised employees working in various service sector organizations in Delhi NCR. 400 employees were surveyed using Google Forms and hard copies of the questionnaire (see Appendix). Employees belonging to lower, middle and senior managerial levels were contacted personally and via LinkedIn. The data collection process took almost two months, from September 2020 to November 2020. Out of the 400 responses, only 276 responses were found usable (69% response rate).

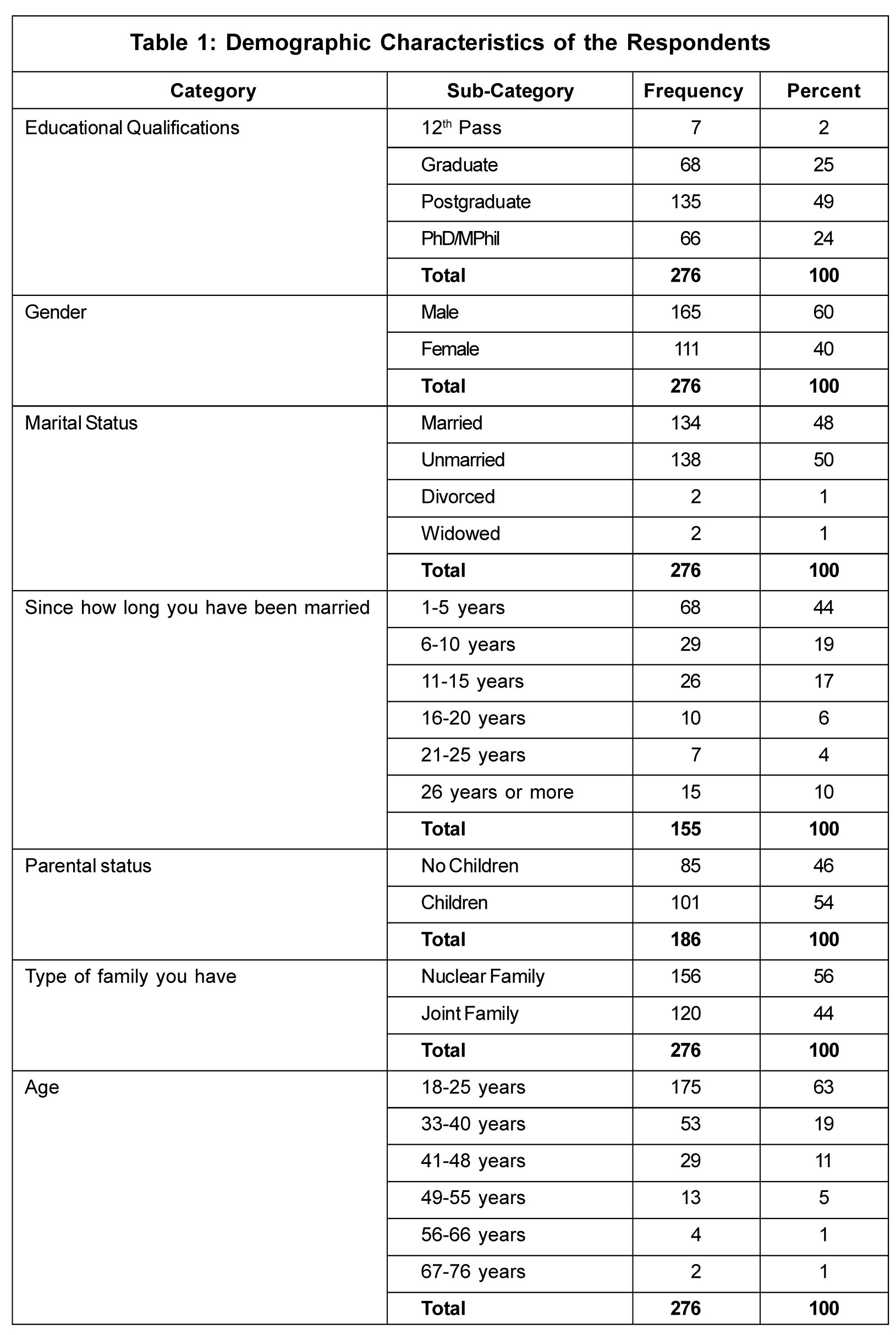

Table 1 lists the demographic characteristics of the respondents. The sample comprised 60% males, and 40% females. With respect to their educational qualification, the maximum number of respondents belonged to the postgraduate category (49%), followed by graduates (25%), and PhD/MPhil (24%). 50% of the respondents were unmarried, 48% married, 1% divorced and 1% widowed. Of the married respondents, 44% remained married for 1 to

5 years, followed by 6 to 10 years (19%) and 11 to 15 years (17%). As for their parental status, 54% had children and 46% did not. Coming to their family background, 56% belonged to nuclear family structure and 44% to joint family structure. The maximum number of respondents (63%) belonged to the age group of 18 to 25 years, followed by 33 to 40 years (19%) and 41 to 48 years (11%).

Measures

The study was conducted in the Indian context using standard scales. Hence, after expert reviews and suggestions, the survey questions were modified accordingly. The questionnaire had two sections:

- Section 1: Demographic profile of respondents such as age, gender, education, etc.

- Section 2: Questions related to workplace fun, perception of fit and employee engagement.

Workplace Fun: A four-item scale each for socializing with coworkers (Cronbach's Alpha (a) = 0.86) and celebrating at work (Cronbach's Alpha (a) = 0.91) (Table 2) as part of workplace fun was adapted from McDowell (2005). Sample items included "I get the opportunity to socialize with coworkers at work", "I have good friends at work", "Organization holds regular office parties", "Throwing parties to recognize accomplishments is a regular thing in the organization", etc.

Perception of Fit: The scale of Saks and Ashforth (2002) for perception of fit was used in the study. A three-item scale for perception of job fit (Cronbach's Alpha (a) = 0.924) and a three-item scale for perception of organization fit (Cronbach's Alpha (a) = 0.936)

(Table 2) were adapted. Sample scale items comprised "This job fulfills my all needs", "The job is a very good match for me", and "This organization has fulfilled all my needs", etc.

Criterion Variables

Employee Engagement: To measure employee engagement (Cronbach's Alpha (a) = 0.961) (Table 2), Gallup Q12 Index, 10-item scale was adapted from Harter et al. (2002). The sample items were "I know what is expected of me at work", "I have the materials and equipment I need to do my work right", "My supervisor, or someone at work, seems to care about me as a person", etc.

Control Variables

Prior studies in the field of engagement (Mohapatra and Sharma, 2010; Banihani et al., 2013; Madan and Srivastava, 2015; Shukla et al., 2015; Chaudhary and Rangnekar, 2017; Marcus and Gopinath, 2017; and Hasanati, 2018) demonstrated gender, educational qualifications, age, marital status and type of family can be potential predictors of study criteria. Based on these studies, gender, age, educational qualification, type of family and marital status are used as control variables for the study.

All were rated on a seven-point Likert scale that ranged from (1) strongly disagree to (7) strongly agree. IBM SPSS Statistics Version 25 was used to assess overall reliability; Cronbach's coefficient alpha was used to test the reliability of the construct items, which ranged from 0.85 to 0.961 (Table 2). Overall reliability of all the constructs came out to be 0.962. All the reliability figures were acceptable, as per the cut-off of 0.70 (Nunnally, 1978).

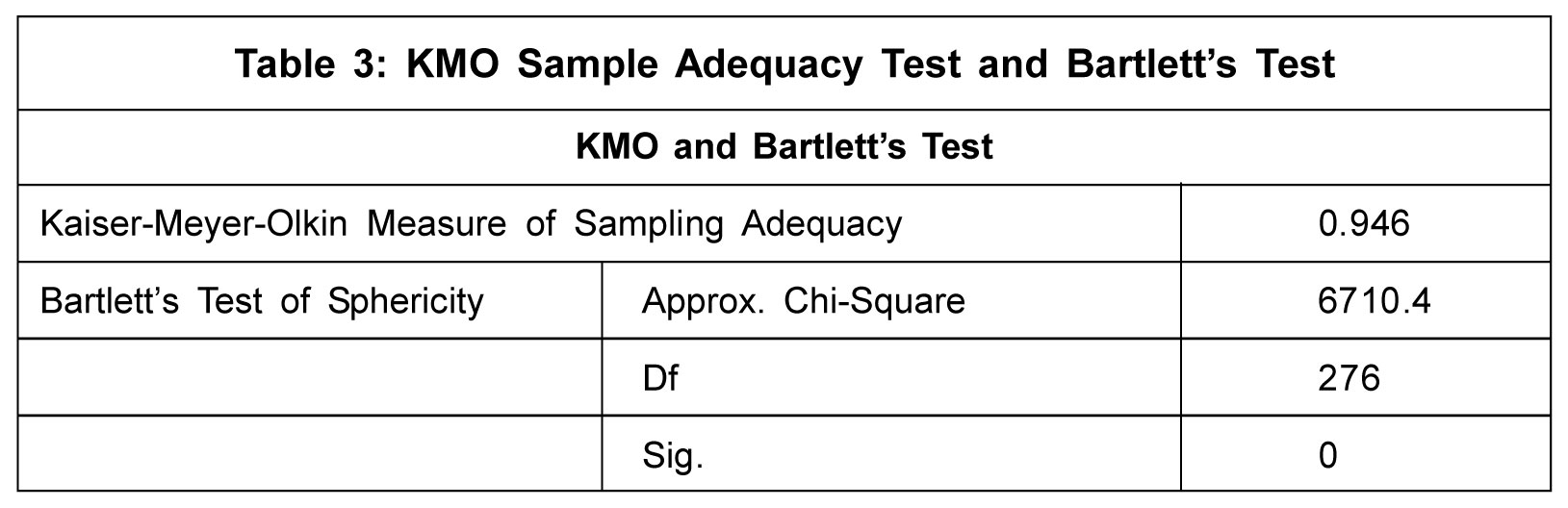

Overall Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett's Test measure to verify sampling adequacy came out to be 0.946. All KMO values for individual constructs were higher than 0.729, which is well over the acceptable limit of 0.5 (Field, 2009) (Table 3).

Measurement Model and Analysis

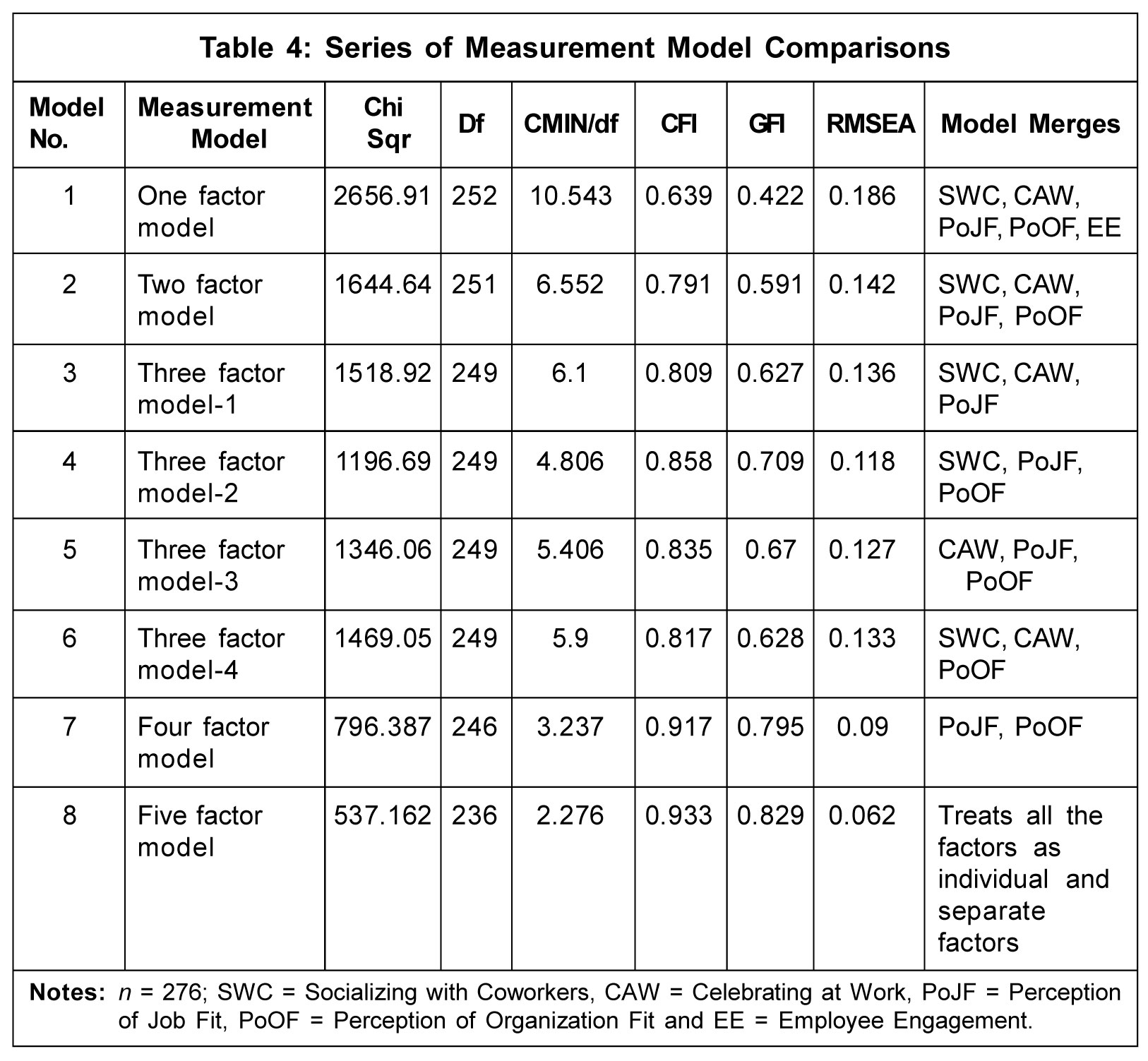

In order to check the validity and fitness of the model Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was conducted using AMOS Version 24. Initially, a series of CFAs (Table 4) were conducted to test and examine model fitness and check which model fits the validity parameters (Anderson and Gerbing, 1988). The five-factor measurement model shows all

the five components separately, i.e., Socializing with coworkers, Celebrating at work, Perception of Job Fit, Perception of Organization Fit and Employee Engagement fit the data well with following indices/parameters: c2 = 537.162, df = 236, CMIN/df = 2.2796 (< 5.0; (Wheaton et al., 1977)), CFI = 0.933 (≥ 0.90; (Bentler, 1990)), GFI = 0.829 (Doll et al., 1994; and Baumgartner and Homburg, 1996), and RMSEA = 0.062 (< 0.07; (Steiger, 2007)). All indicators of model fitness were found to be statistically significant with factor loadings (p < 0.01) reporting convergent validity (Anderson and Gerbing, 1988). Then discriminant validity was tested in several ways.

First, the fitness indices for one-factor measurement model (Model 1) shows poor fit c2 = 2656.907; df = 25299; CFI = 0.639; GFI = 0.422; and RMSEA = 0.186. After that random models were tested for validity (Table 4) and the comparative chart shows that five-factor model (Model 5) best fits the data requirement.

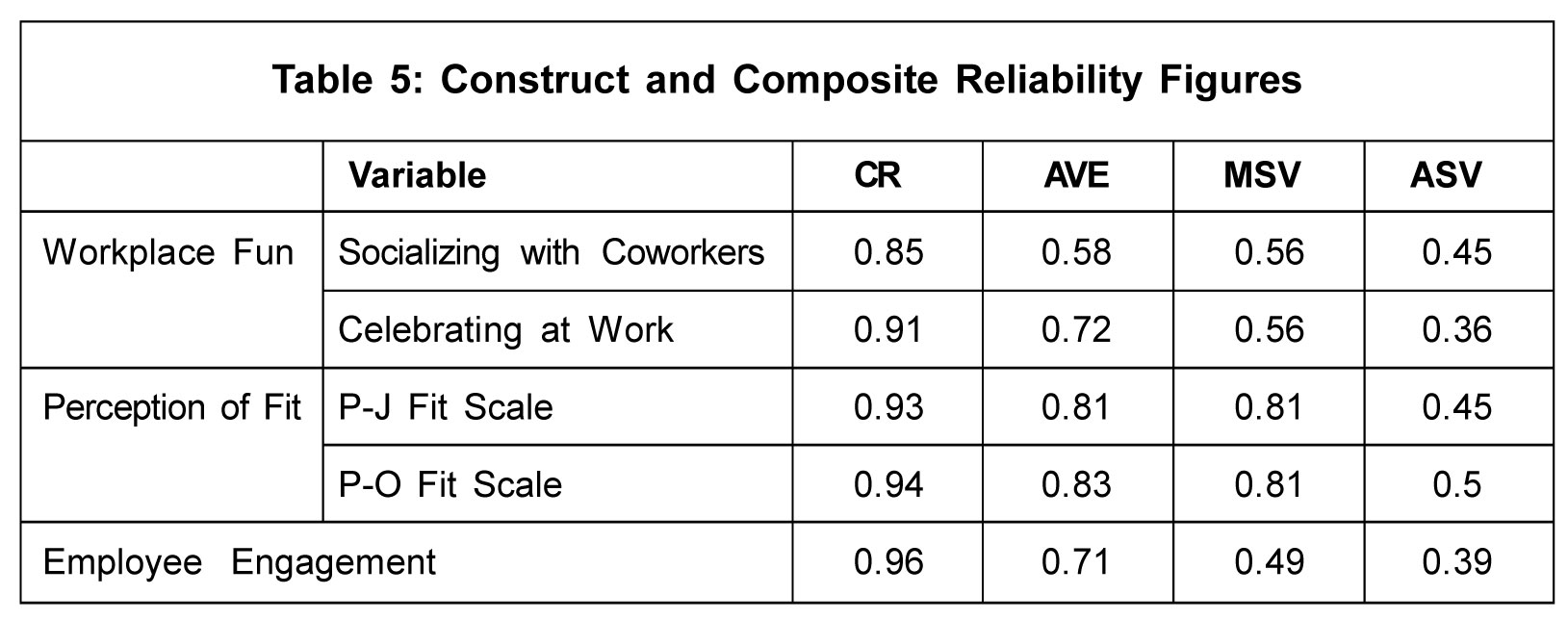

Finally, for five-factor model (Model 5) that best fits the data requirement (construct reliability), Composite Reliability (CR) (Table 5) for all the constructs was found to be more

than 0.7 (Kline and Thompson, 2010; and Hair et al., 2016). Further, CR must be greater than AVE and also AVE should be more than 0.50 and the value of Multiple Shared Variance (MSV) needs to be less than AVE (Hair et al., 2016). Since the proposed model satisfies all the construct validity conditions, the model can be concluded to have convergent validity (Table 5).

Descriptive Statistical Analysis

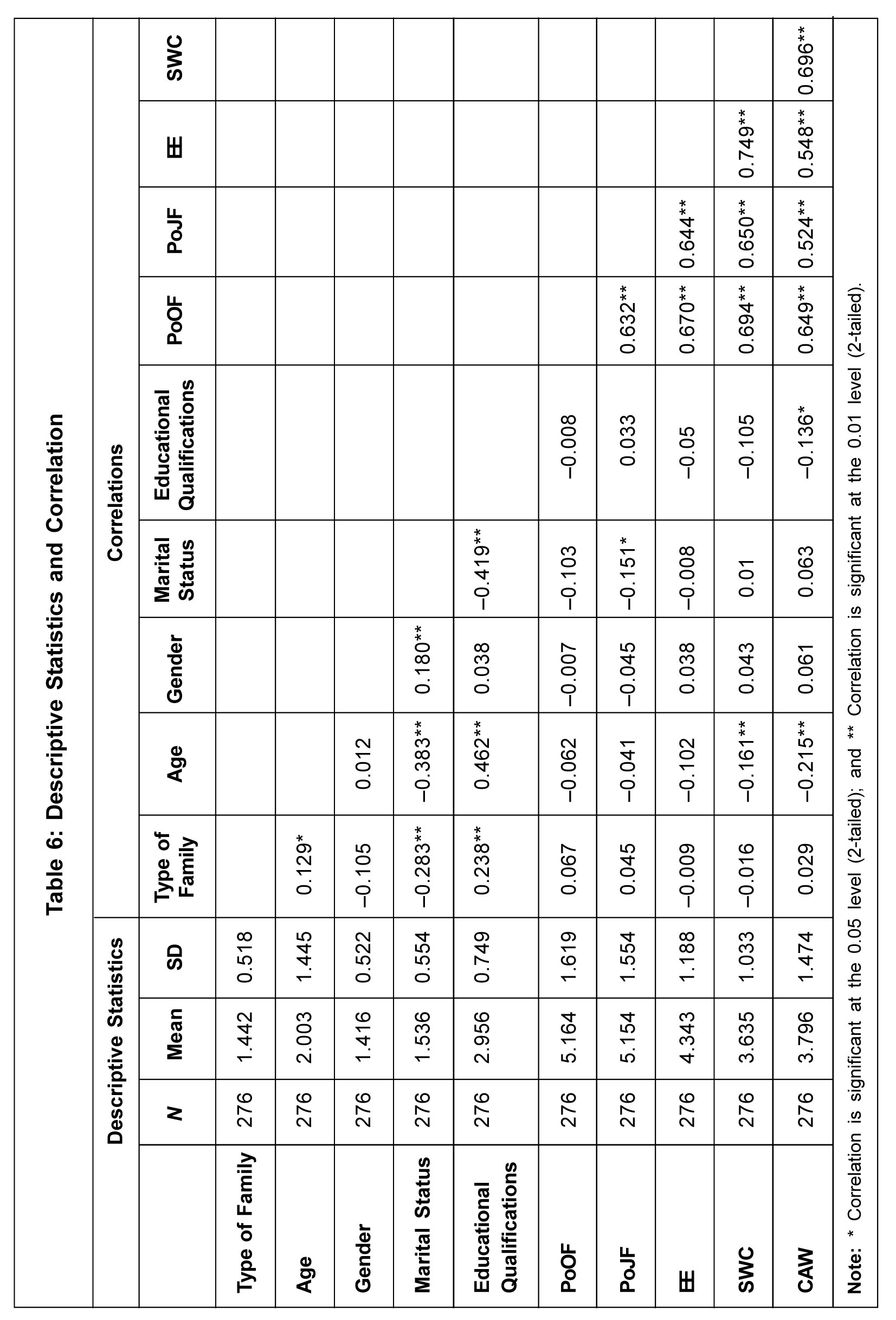

Descriptive statistics is presented in Table 6, representing means, standard deviations and correlations for the variables used in the study, showing the degree of correlations among the study variables. All the correlation matrices were in the projected directions, which provided further conditions to proceed ahead with hypothesis testing. The analysis shows the relation between dimension of workplace fun and perception of fit (r = 0.694**, r = 0.650** at p < 0.01), but since no relevant literature was found supporting the relationship, no hypothesis was framed for the same. Perception of Organization Fit (PoOF), Perception of Job Fit (PoJF); and Socializing with Coworkers (SWC) and Celebrating at Work (CAW) as dimensions of Workplace fun were all found to be significantly associated with employee engagement with r = 0.670**, r = 0.644**, r = 0.749**, r = 0.548** respectively at p < 0.01. Overall, these initial findings advance primary support to our hypotheses H1, H2, H3 and H4 and give confidence to proceed for further analysis.

Correlation analysis concludes that socializing with coworkers and celebrating at work as dimensions of workplace fun are positively associated with one another (r = 0.696, p < 0.01), thus satisfying Objective 1. Objective 2 is also satisfied with this analysis. Perception of job and organization fit as dimensions of perception of fit are also found to be positively correlated with one another (r = 0.632, p < 0.01).

Hypothesis Testing

Now to perform a more rigorous analysis, hierarchical multiple regression process was further conducted to test the hypotheses considering control variable, using IBM SPSS software. The researchers shifted from AMOS to SPSS since categorical control variables

cannot be undertaken in AMOS, which works on reflective constructs only. Considering the role of control variable, they were entered in the first block of regressing analysis in SPSS Version 24; then in the second block, perception of fit and workplace fun-related variable were entered to estimate change in R2. Although the study proposed type of family, gender, age, marital status, and educational qualifications as control variables as stated in previous studies, for this study, they did not prove to be a significant contributor to employee engagement. Overall, the model summary states that these demographic factors contribute only 1.6% towards employee engagement (R2 = 0.016), hence the relationship is not significant (Sig value = 0.491).

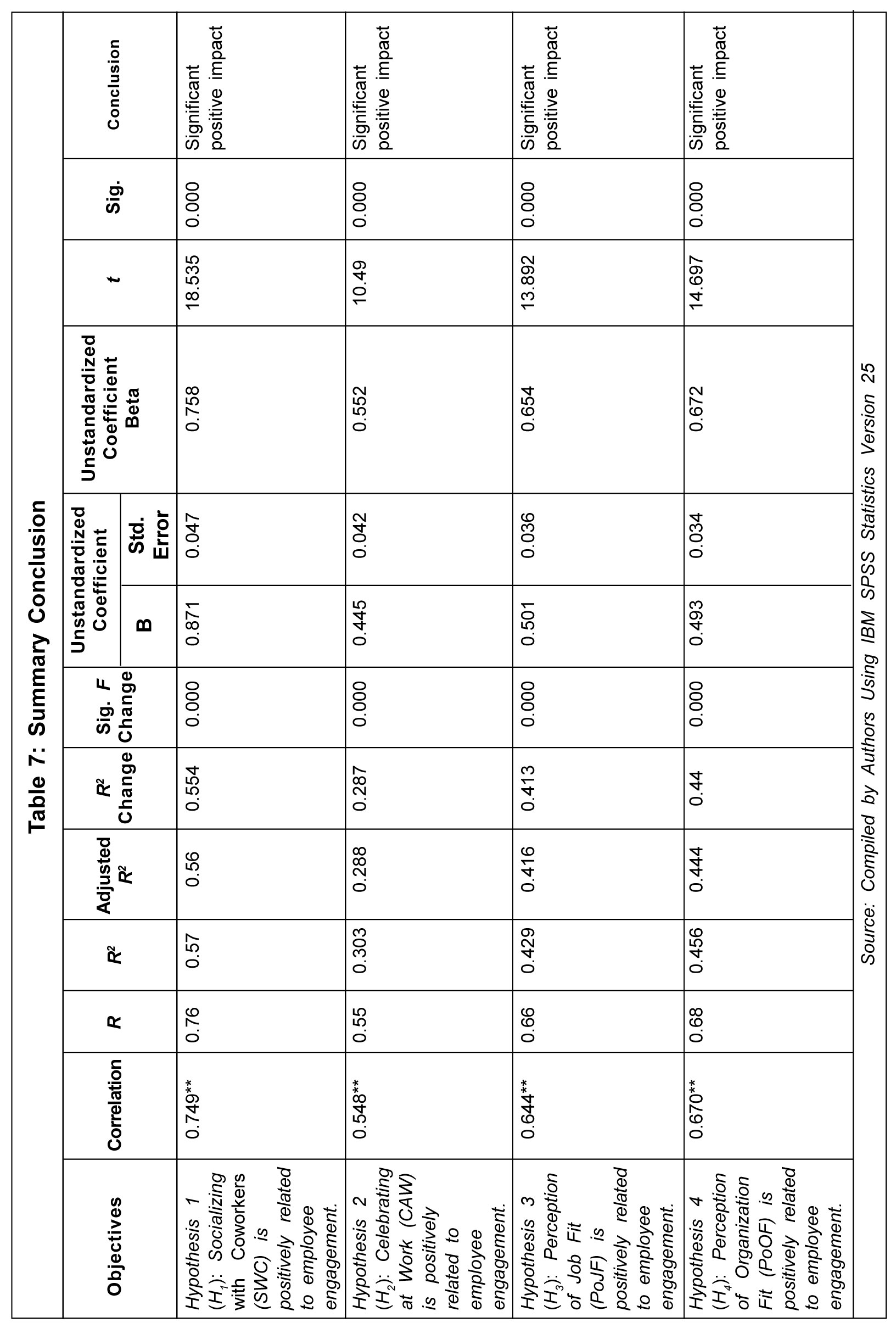

H1 proposed socializing with coworkers (SWC) is positively related to work engagement. Based on control variables such as age, gender, marital status, educational qualifications, and type of family, the multiple regression analysis findings show that SWC makes up 55.4% of EE. (R2 Change = 0.554), which shows significant contribution (Sig. F Change = 0.000). Coefficients table shows SWC has a significant positive impact on EE (p < 0.005, Beta = 0.758, t = 18.535) (Table 6).

Further, the results of multiple regression analysis model reports Celebrating at Work (CAW) contributes 28.7% towards EE (R2 Change = 0.287), which shows significant contribution (Sig. F Change = 0.000). Coefficients table shows CAW has a significant positive impact on EE (p < 0.005, Beta = 0.552, t = 10.490). With this, H2 is also accepted, i.e., CAW is positively related to work engagement (Table 7).

Perception of Job Fit (PoJF) was also found to be positively related to job engagement H3. The model reported that PoJF contributes 41.3% towards EE (R2 Change = 0.413), which shows significant contribution (Sig. F Change = 0.000). Coefficients table shows PoJF has a significant positive impact on EE (p < 0.005, Beta = 0.654, t = 13.892)

(Table 7).

The model summary reports that PoOF contributes 44% towards EE (R2 Change = 0.440), which shows significant contribution (Sig. F Change = 0.000). Coefficients table shows PoOF has a significant positive impact on EE (p < 0.005, Beta = 0.672, t = 14.697)

(Table 7). Hence, H4, which states that PoOF is positively related to job engagement is also supported (Table 7).

Implications of the Study

Organizations post Covid-19 are facing challenges with regard to promoting engagement among employees. Special attention is being given to engagement of employees, which is also established as a key determinant of employee performance (Gruman and Saks, 2011). Engagement has not only the potential to impact retention, loyalty of employees and productive output, but also a strong link with enhanced employee retention, improved stakeholder value and customer satisfaction (Lockwood, 2007). Keeping the benefits of engaged employees in view, the present study has significant implications for the

managers and the organization as a whole with regard to deciding the perception of fit criteria and in what way employees can be more engaged by adopting workplace fun. The overall findings of this study suggest that if employees have PoJF and PoOF, they will have a strong association with the organization and more engagement as well. Fun events like playing games via video conference, remote workout sessions and team lunch/ dinner can be organized by companies. 61% of employers have implemented and 6% are yet to implement initiatives to engage employees (Peppercomm, 2020). Workplace fun such as recognition awards, parties, and social gatherings not only drive employee performance but also create harmony in the workplace (Karl and Peluchette, 2005). Also, organizations must make the families of employees involved and happy, since employees will be working at home, and hence, they must feel comfortable and secure, especially during times like the pandemic. The employees who are interested in their job are more likely to concentrate, enjoy it, and comprehend the tasks and implications of their employment. The psychological state of a worker has a significant impact on job satisfaction (May et al., 2004). Person-job fit is one of those psychological conditions (Juhdi et al., 2013). Employees having talents and abilities in line with the job's criteria are highly engaged in their work.

Conclusion

The study explored the relationship between perception of fit and employee engagement. Secondly, the study examined the impact of workplace fun represented by two dimensions, CAW and SWC, on EE. The findings of the study reveal that engagement is highly driven by workplace fun arranged by the organization and the perception of fit shown by the employees. When employees get the opportunity to SWC and have frequent opportunities to CAW, both these aspects will have a significant positive impact on EE. The findings of the study are supported by those of Sonnentag (2003) and Schaufeli and Bakker (2004), which also depict a significant positive impact of workplace fun on EE. Surprisingly, the results of the study are in contradiction to the findings of Plester and Ann (2016) who conducted an ethnographic study and found that for some employees, workplace fun gives a "refreshing break", resulting in superior engagement level at work; for others, fun causes distractions from work and the outcome may be high level of disengagement.

Also, when employees have PoJF, they are better engaged. May et al. (2004), Kristof-Brown et al. (2005), Shuck et al. (2011), Juhdi et al. (2013) and Hussain and Ali (2016) also found positive impact of job fit on employee engagement. PoOF also helps to drive engagement level among employees, leading to better organizational productivity and efficiency, which is further supported by May et al. (2004), Lascbinger and Wong (2006), Warr and Inceoglu (2012) and Hussain and Ali (2016).

Limitations: Firstly, the data was collected using a standardized scale which might not be able to cover each and every aspect of the constructs. Secondly, given the above, common method variance might occur (Podsakoff and Organ, 1986). Thirdly, the study is cross-sectional in nature, hence might not be valid and applicable for all time frames. Fourthly, the data was collected from service sector employees only, hence the results cannot be generalized for employees in other sectors. Hence, future researchers can study the results across various sectors and can adopt a comparative analysis model for their studies.

References

- Aitken-Fox E, Coffey J, Dayaram K et al. (2020), "Covid-19 and the Changing Employee Experience", LSE Business Review. Retrieved on May 23, 2021, from https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/businessreview/2020/06/24/covid-19-and-the-changing-employee-experience/

- Anderson J C and Gerbing D W (1988), "Structural Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-Step Approach", Psychological Bulletin, Vol. 103, No. 3, pp. 411-423.

- Arthur W, Bell S, Villado A and Doverspike D (2006), "The Use of Person-Organization Fit in Employment Decision Making: An Assessment of Its Criterion-Related Validity", Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 91, No. 4, pp. 786-801.

- Banihani M, Lewis P and Syed J (2013), "Is Work Engagement Gendered?", Gender in Management: An International Journal, Vol. 28, No. 7, pp. 400-423, Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Baumgartner H and Homburg C (1996), "Applications of Structural Equation Modeling in Marketing and Consumer Research: A Review", International Journal of Research in Marketing, Vol. 13, No. 2, pp. 139-161.

- Becker F W and Tews M J (2016), "Workplace Fun at Work: Do They Matter to Hospitality Employees", Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism, Vol. 15, No. 3, pp. 279-296.

- Biswas S and Bhatnagar J (2013), "Mediator Analysis of Employee Engagement: Role of Perceived Organizational Support", P-O Fit, Organizational Commitment and Job Satisfaction, VIKALPA, Vol. 38, No. 1, pp. 27-40.

- Biswas S and Varma A (2007), "Psychological Climate and Individual Performance in India: Test of a Mediated Model", Employee Relations, Vol. 29, No. 6, pp. 664-676.

- Cable D M and DeRue D S (2002), "The Convergent and Discriminant Validity of Subjective Fit Perceptions", Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 87, No. 5, pp. 875-884.

- Caccamese L (2012), Five Ways to Have More Workplace Fun. Retrieved on January 16, 2021, from http://www.greatplacetowork.com/publications-and-events/blogs-and-news/981

- Chaudhary R and Rangnekar S (2017), "Socio-Demographic Factors, Contextual Factors, and Work Engagement: Evidence from India", Emerging Economy Studies, Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 1-18, Sage Publications.

- Collins J and Porras J I (1997), Built to Last: Successful Habits of Visionary Companies, HarperCollins, New York.

- Dana L P (2000), "Creating Entrepreneurs in India", Journal of Small Business Management, Vol. 38, No. 1, pp. 86-91.

- Deal and Kennedy (1999), The New Corporate Cultures, Perseus Books, Reading, MA.

- Demerouti E, Bakker A, Nachreiner F and Schaufeli W (2001), "The Job-Demands Resources Model of Burnout", Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 86, No. 3, pp. 499-512.

- Dhingra A and Agarwal N (2020), "Covid-19 Lockdown: Managing and Engaging with Employees. Prudent: The Future of Insurance, Mumbai, India". Retrieved on August 20, 2020, from http://www.asinta.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/COVID-19-LOCK DOWN-MANAGING-AND-ENGAGING-WITH-EMPLOYEES.pdf

- Doll W, Xia W and Torkzadeh G (1994), "A Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the End-User Computing Satisfaction Instrument", MIS Quarterly, Vol. 18, No. 4, pp. 357-369.

- Edwards J (1991), Person-Job Fit: A Conceptual Integration, Literature Review, and Methodological Critique, John Wiley & Sons, Oxford.

- Field A (2009), Discovering Statistics Using SPSS, Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA.

- Ford R C, McLaughlin F S and Newstrom J W (2003), "Questions and Answers About Fun at Work", Human Resource Planning, Vol. 26, No. 4, pp. 18-33.

- Frank F D, Finnegan R P and Taylor C (2004), "The Race for Talent: Retaining and Engaging Workers in the 21st Century", Human Resource Planning, Vol. 27, No. 3, pp. 12-25.

- Gruman J and Saks A (2011), "Performance Management and Employee Engagement", Human Resource Management Review, Vol. 21, No. 2, pp. 123-136.

- Hair Jr J, Hult G, Ringle C and Sarstedt M (2016), A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd Edition, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA.

- Harter J K, Schmidt F L and Hayes T L (2002), "Business-Unit-Level Relationship Between Employee Satisfaction, Employee Engagement, and Business Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis", Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 87, No. 2, pp. 268-279.

- Hasanati N (2018), "Effect of Demography Factor and Employee Engagement to Organizational Commitment", Analitika, Vol. 10, No. 1, pp. 54-59.

- Hussain S, Lei S, Akram T, Haider M J, Hussain S H and Ali M (2018), "Kurt Lewin's Change Model: A Critical Review of the Role of Leadership and Employee Involvement in Organizational Change", Journal of Innovation and Knowledge, Vol. 3, No. 3, pp. 123-127.

- Juhdi N, Pawan F and Hansaram R (2013), "HR Practices and Turnover Intention: The Mediating Roles of Organizational Commitment and Organizational Engagement in a Selected Region in Malaysia", The International Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 24, No. 15, pp. 3002-3019.

- Kahn W (1996), "An Exercise of Authority", Organizational Behavior Teaching Review, Vol. 14, No. 2, pp. 28-42.

- Karl K and Peluchette J (2005), "Does Workplace Fun Buffer the Impact of Emotional Exhaustion on Job Dissatisfaction? A Study of Healthcare Worker", Journal of Behavioral and Applied Management, Vol. 7, No. 2, pp. 128-141.

- Karl K A, Peluchette J V, Hall L and Harland L K (2005), "Attitudes Toward Workplace Fun: A Three Sector Comparison", Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, Vol. 12, No. 2, pp. 1-17.

- Kline R and Thompson B (2010), Promise and Pitfalls of Structural Equation Modeling in Gifted Research, Gifted Methodologies, American Psychological Association Books, Washington, DC.

- Kristof A (1996), "Person-Organization Fit: An Integrative Review of Its Conceptualizations, Measurement, and Implications", Personnel Psychology, Vol. 49, No. 1, pp. 1-49.

- Kristof-Brown A L, Zimmerman R D and Johnson E (2005), "Consequences of Individuals' Fit at Work: A Meta-Analysis of Person-Job, Person-Organization, Person-Group, and Person-Supervisor Fit", Personnel Psychology, Vol. 58, No. 2, pp. 281-342.

- Lascbinger H and Wong C G (2006), "The Impact of Staff Nurse Empowerment on Person-Job Fit and Work Engagement/Burnout", Nursing Administration Quarterly, Vol. 30, No. 4, pp. 358-367.

- Lauver K and Kristof-Brown A (2001), "Distinguishing Between Employees' Perceptions of Person-Job and Person-Organization Fit", Journal of Vocational Behavior, Vol. 59, No. 3, pp. 454-470.

- Lewin K (1951), Field Theory in Social Science: Selected Theoretical Papers, Tavistock Publications, London.

- Lockwood N (2007), "Leveraging Employee Engagement for Competitive Advantage: HR's Strategic Role", HR Magazine, Vol. 52, (3 Special Section), pp. 1-11.

- Lund S, Madgavkar A, Manyika J et al. (2021), "The Future of Work After Covid-19". Retrieved on July 29, 2021, from https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/future-of-work/the-future-of-work-after-covid-19

- Madan P and Srivastava S (2015), "Employee Engagement, Job Satisfaction & Demographic Relationship: An Empirical Study of Private Sector Bank Managers", FIIB Business Review, Vol. 4, No. 2, pp. 53-62.

- Marcus A and Gopinath N M (2017), "Impact of the Demographic Variables on the Employee Engagement: An Analysis", ICTACT Journal on Management Studies, Vol. 3, No. 2, pp. 502-510.

- Maslach C and Leiter M (2008), "Early Predictors of Job Burnout and Engagement", Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 93, No. 3, pp. 498-512.

- May D, Gilson R and Harter L (2004), "The Psychological Conditions of Meaningfulness, Safety and Availability and the Engagement of the Human Spirit at Work", Journal of Occupational and Organisational Psychology, Vol. 77, No.1, pp. 11-37. DOI:10.1348/096317904322915892

- McDowell T (2005), "Fun at Work: Scale Development, Confirmatory Factor Analysis, and Links to Organizational Outcomes", Doctoral dissertation, Alliant International University, Dissertation Abstracts International, Vol. 65, 6697.

- Meyer J and Herscovitch L (2001), "Commitment in the Workplace: Toward a General Model", Human Resource Management Review, Vol. 11, No. 3, pp. 299-326.

- Mohapatra M and Sharma B R (2010), "Study of Employee Engagement and Its Predictors in an Indian Public Sector Undertaking", Global Business Review, Vol. 11, No. 2, pp. 281-301, Sage Publications.

- MoneycontrolNews (2020), "Deloitte to Shut 4 Offices, to Transfer All Staff to Permanent Work from Home". MoneyControl. Retrieved on November 5, 2020, from https://www.moneycontrol.com/news/business/deloitte-to-shut-4-offices-will-transfer-all-staff-to-permanent-work-from-home-5997081.html

- Negi A and Pant R (2023), "The Development of Employee Engagement: A Bibliometric Analysis Based on Vosviewer", Shodh Prabha (UGC Care Journal), Vol. 48, No. 6, pp. 75-84

- Negi A, Pant R and Kishor N (2021), "Effects of Covid-19: Redefining Work from Home & Employee Engagement", Transnational Marketing Journal, Vol. 9, No. 3, pp. 521-538. doi:https://doi.org/10.33182/tmj.v9i3.1298

- Negi A, Pant R and Kishor N (2022), "Employee Engagement: A Study of Select Service Sector Organisations Using Qualitative and Quantitative Approach", International Journal of Technology Transfer and Commercialization, Vol. 19, No. 1, p. 1. doi:10.1504/IJTTC.2022.10038751

- Nicastro D (2020), 8 Employee Engagement Ideas for a Changing Workforce, Employee Experience, Reworked. Retrieved on August 20, 2020, from https://www.reworked.co/employee-experience/8-employee-engagement-ideas-for-a-changing-workforce/

- Nunnally J (1978), Psychometric Theory, 2nd Edition, McGraw-Hill, New York.

- O'Reilly C, Chatman J and Caldwell D (1991), "People and Organizational Culture: A Profile Comparison Approach to Assessing Person-Organization Fit", Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 34, No. 3, pp. 487-516.

- Owler K, Morrison R and Plester B (2010), "Does Fun Work? The Complexity of Promoting Fun at Work", Journal of Management & Organization, Vol. 6, No. 3, pp. 238-352.

- Parkers L P, Bochner S and Schneider S (2001), "Person-Organization Fit Across Cultures: An Empirical Investigation of Individualism", Applied Psychology: An International Review, Vol. 50, No. 1, pp. 81-108.

- Peppercomm (2020), "Special Report: How Companies Are Engaging Employees During Covid-19", The Institute for Public Relations and Peppercomm. Retrieved on September 8, 2020, from https://instituteforpr.org/wp-content/uploads/PC_IPR_ Coronavirus_Phase2_FINAL-4-22_compressed.pdf

- Plester B and Ann H (2016), "Fun Times: The Relationship Between Fun and Workplace Engagement", Employee Relations: The International Journal, Vol. 38, No. 3, pp. 322-350, Emerald Publishing Group. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/ER-03-2014-0027

- Reuters (2020), "Amazon Extends Work from Home Option Till June", The Hindu. Retrieved on November 2, 2020, from https://www.thehindu.com/business/Industry/amazon-extends-work-from-home-option-till-june/article32905729.ece#

- Rich B, Lepine J and Crawford E (2010), "Job Engagement: Antecedents and Effects on Job Performance", Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 53, No. 3, pp. 617-635.

- Saks A (2006), "Antecedents and Consequences of Employee Engagement", Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 21, No. 7, pp. 600-619.

- Saks A M and Ashforth B E (2002), "Is Job Search Related to Employment Quality? It All Depends on the Fit", Journal of Applied Psychology - American Psychological Association, Vol. 87, No. 4, pp. 646-654.

- Schmidt E and Rosenberg J (2014), How Google Works, Grand Central, New York.

- Schneider B (2001), "Fits About Fit", Applied Psychology: An International Review, Vol. 50, No. 1, pp. 141-152.

- Schaufeli W B and Bakker A B (2004), "Job Demands, Job Resources, and Their Relationship with Burnout and Engagement: A Multi-Sample Study", Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 25, No. 3, pp. 293-315. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.248

- Scroggins W A (2008), "Antecedents and Outcomes of Experienced Meaningful Work: A Person-Job Fit Perspective", Journal of Business Inquiry, Vol. 7, No. 1, pp. 68-78.

- Shuck B Jr, Reio T G and Rocco T S (2011), "Employee Engagement: An Examination of Antecedent and Outcome Variables", Human Resource Development International, Vol. 14, No. 4, pp. 427-445.

- Shukla S, Adhikari B and Singh V (2015), "Employee Engagement - Role of Demographic Variables and Personality Factors", Amity Global HRM Review, Vol. 5, pp. 65-73.

- Sonnentag S (2003), "Recovery, Work Engagement, and Proactive Behavior: A New Look at the Interface between Nonwork and Work", Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 88, No. 3, p. 518.

- Steiger J (2007), "Understanding the Limitations of Global Fit Assessment in Structural Equation Modeling", Personality and Individual Differences, Vol. 42, No. 5, pp. 893-98.

- Tews M J, Michel J W and Allen D G (2014), "Fun and Friends: The Impact of Workplace Fun and Constituent Attachment on Turnover in a Hospitality Context", Human Relations; Studies Towards the Integration of the Social Sciences, Vol. 67, No. 8, pp. 923-946.

- Vorhauser-Smith S (2013), "How the Best Places to Work are Nailing Employee Engagement". Retrieved on December 12, 2020, from http://www.forbes.com/sites /sylviavorhausersmith /2013/08/14/how-the-best-places-to-work-are-nailing-employee-engagement/print/

- Vuuren V M, Bernard P V, Menno D T and Seydel E (2007), "Why Work? Aligning Foci and Dimensions of Commitment Along the Axes of the Competing Values Framework", Personnel Review, Vol. 37, No. 1, pp. 47-65.

- Warr P and Inceoglu I (2012), "Job Engagement, Job Satisfaction, and Contrasting Associations with Person-Job Fit", Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, Vol. 17, No. 2, pp. 129-138. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0026859