October'23

The IUP Journal of Organizational Behavior

Archives

Role of Experiential Knowledge in Women's Empowerment Through Self-Help Groups: An SEM Analysis in Jammu & Kashmir

John Mohammad Paray

Research Scholar, Department of Political Science, University of Kashmir, Srinagar, J&K, India.

E-mail: johnmohammadparayresearch123@gmail.com

Increasing women's empowerment through self-help group (SHG) initiatives is one of the widely preferred programs in India. The impact of SHGs on women's lives has been the subject of numerous studies, but no complete assessment has yet taken place, particularly in addressing the multidimensional aspects of empowerment. This study assumes that group members' experience and knowledge play a moderating role in the linkage between women's empowerment and their involvement in SHGs. However, the primary rationale of this work is to evaluate the impact of women's involvement in SHGs on their empowerment. The study used a quantitative design, including 267 (functional) questionnaires. A survey was done to gather data from women members of different SHGs in the Union Territory of Jammu & Kashmir. Regression analysis showed that women's participation in SHGs influences all four dimensions of women empowerment, viz., economic, social, psychological, and political.

Introduction

Research shows that women's equality in the workplace, healthcare, and democratic freedom have improved, but some structural and social obstacles remain (Sen, 2001; Duflo, 2012; and Cohen and Karim, 2022). About half of the world's underprivileged live in South Asia, according to the 2019 Human Development Report, and 70% of low-income people are women (Kotte, 2019). The scenario has been even more imperfect for rural women over the previous two decades (Kotte, 2019; and Zulfiqar, 2022). Therefore, women empowerment is essential on multiple fronts to improve their conditions (Nayak and Panigrahi, 2020; and Rodriguez, 2022). Economic development and empowerment have a tenuous connection (Duflo, 2012) that is unlikely to hold over time. In addition, other domains of empowerment, such as social, political and economic, are also inherently vital (Brody et al., 2017). It is critical to support legislation and initiatives aimed at achieving gender parity and women empowerment (Jakimow and Kilby, 2006). Many developing countries use programs like Self-Help Groups (SHGs) to give women more economic independence and empowerment, especially in South Asia, including India (Sato et al., 2022).

SHGs have played a crucial role in women's empowerment through different mechanisms such as easy accessibility to monetary resources, social support, political empowerment, etc. (Brody et al., 2017; and Rai and Shrivastava, 2021) through their participation in such programs. Several studies have analyzed the effect of women's SHGs on their lives, but no comprehensive examination has yet taken place, especially concerning the multidimensional aspects of empowerment. In addition, research suggests that some variables also play an essential, though indirect, part in women's empowerment (Kandpal, 2022; and Stenersen et al., 2022). There are many studies on female empowerment via SHGs (Kandpal, 2022; Nichols, 2022; and Sato et al., 2022). Although SHGs have been shown to have increased women's access to and control of resources (credit, income), as well as their decision-making power (increased income, major household decisions, household assets), it is not well studied whether or not this has led to empowerment outcomes, especially their political, social and psychological empowerment (Kabeer, 2001 and 2010; and Quisumbing et al., 2010). Therefore, examining the relationship between women's participation in SHGs and their empowerment from multiple dimensions becomes critical. Moreover, many of these studies must include an important variable: the group's experiential knowledge. The group's experiential knowledge is essential to women's empowerment (Singh et al., 2022). But research has shown that experience/knowledge often moderates many social science studies (Wei et al., 2019). In this paper, we have assumed that group members' experiential knowledge plays a moderating role in the link between women's empowerment and their participation in SHGs. However, the main aim of this paper is to study the influence of women's participation in SHGs on their empowerment.

Literature Review

Self-Help Groups

SHGs include a group of people who work collectively to find answers to their most fundamental problems. The primary objective of SHGs is to assist residents, particularly women, in developing a preference for saving small amounts of money (Chatterjee et al., 2018). SHGs aim to improve economically disadvantaged women's access to technical and managerial expertise (Kandpal, 2022). People living under the poverty line who belong to an SHG save regularly in a shared fund and then use the funds to provide emergency loans, which are given out at low-interest rates and with no requirement for collateral, as agreed on by the group (Nayak, 2015). SHGs are an excellent source of motivation and resources.

Social Empowerment

A greater level of self-assurance was indicated by women SHG members speaking in front of people and engaging with various stakeholders to bring about good community changes (Kabeer, 2011; and Pattenden, 2018). SHG members' networking experiences substantially departed from the domestic sphere, where they spoke primarily to family members and close friends. Many women reported that they were able to make better choices and create lasting changes in their lives due to the assistance they received from their groups. Some of the studies (Ramachandar and Pelto, 2009; and Dahal, 2014) examined the views of women who were members of SHGs and found that these women were treated with more respect by their peers.

Financial Empowerment

Removing discrimination in the educational field and creating professional possibilities for women are frequently cited as examples of economic empowerment of women (Sato et al., 2022). Even though these women are not financially poor, cultural or religious barriers have prevented them from achieving financial independence. However, they tend to be on a lower socioeconomic scale in most cases (Shireesha, 2019). The novelty of dealing with money gave women a sense of empowerment. It was only after joining an SHG that many of these women could purchase, sell, and keep accounts of products. Many studies have shown that after joining an SHG, women stated they could better manage their money (Kabeer, 2011; and Sahu and Singh, 2012).

Political Empowerment

According to the findings of multiple papers, women's involvement in an SHG serves as a "stepping stone" toward greater social participation rather than a political act per se (Mathrani and Periodi, 2006). With the help of social events and political networking, SHG members are exposed to the importance of women's rights and get access to political power (Dahal, 2014). It also prompted them to stand out on political issues like accountability and openness (Sahu and Singh, 2012). Furthermore, women who participated in village governments said that SHG participation allowed them to rise to leadership positions (Kilby, 2011). Even in the smallest political acts, women could identify the obstacles preventing them from improving their communities (Ramachandar and Pelto, 2009). As their husbands and other community members came to accept them, two other groups of women found that their political efforts picked up speed and became stronger (Ramachandar and Pelto, 2009).

Psychological Empowerment

Analyzing one's power and developing an empowered attitude is the process of psychological empowerment, which refers to one's ability to manage one's life and make choices (Khan et al., 2023). In rural women, SHGs instill a strong sense of self-belief and self-determination that helps them succeed in their daily tasks (Shireesha, 2019). Participatory empowerment literature (Zimmerman, 1990) claimed that community engagement increases psychological empowerment. Khan et al. (2023) showed that SHG is indispensable to emotional empowerment.

Group's Experiential Knowledge

In SHGs, members are eager to share their personal experiences (Kennedy et al., 1994). Experiential knowledge can come from many different places, like one's own life or the lives of others (Borkman, 1976). While professional knowledge is analytical and built on ideas and scientific principles, experiential knowledge is not (Borkman, 1990). By exchanging their experiences, the group members are better equipped to identify and formulate strategies for resolving an issue. The idea of SHGs has remained ambiguous, even though experiential knowledge is a criterion for characterizing the groups in study literature (Schubert and Borkman, 1994).

Participation

In an SHG, one's level of engagement is defined as the extent to which one is actively involved in the different SHG events (Nayak and Panigrahi, 2020). Participation is often equated with membership, which has been quantified in terms of "yes" or "no" replies in most research (Parker, 1983). However, several studies have shown that involvement is varied. An oversimplified way of measuring participation necessitates a more exact measurement (Nayak and Panigrahi, 2020). Chapin (1928) measured only formal social engagement, one of the earliest efforts to quantify social participation.

Theoretical Framework and Hypothesis Formulation

The Learned Hopefulness Theory proposed by Zimmerman (1990) is used in this study. According to this view, participation and empowerment are linked. Individuals acquire and use techniques that allow them to create a feeling of psychological empowerment via learned hopefulness, as defined by Zimmerman (1990). According to this notion, participation in community groups and activities improves problem-solving abilities and increases social mastery and control. Participation in community groups has been shown to have a beneficial and direct impact on psychological empowerment and other aspects, such as economic, social and political. Empowerment through SHGs follows a participatory approach, and the Theory of Learned Hopefulness discusses the participatory approach to empowerment. Therefore, we have adopted this theory as the basis of our hypothesis development.

According to Sharma (2008), women's involvement in SHGs does enable the emergence of political awakening amongst women. In a similar vein, Madhok's (2013) investigation of women's empowerment workers in Rajasthan reveals how while "failing" at the development job entrusted to them, exposure to "rights discourse" helped them to build new modes of perceiving themselves and their relationship to the state. Women's mobility through SHGs is still a measurement tool for empowering gains and an explanatory variable for globally prioritized development objectives, including economic growth (Brody et al., 2017). SHGs provide an important avenue for economic empowerment for disempowered women (Nichols, 2022; and Siwach et al., 2022). SHG women members can also earn and adjust their budgets and shopping habits due to their involvement in SHGs, leading to economic empowerment (Kabeer, 2008 and 2010). Women in SHGs experience economic empowerment and a better standard of living (Kandpal, 2022). Women's participation in SHGs has also had its effects on their behavioral and psychological empowerment (Aruna and Jyothirmayi, 2011; and Dubey

et al., 2021). Studies have also revealed that SHGs allow women to gain more self-confidence and self-worth, which leads to enhanced psychological empowerment (Pronyk et al., 2006; and Kim et al., 2009). Women's independence also improved through SHG involvement, leading to social empowerment (De Hoop et al., 2014). Studies have indicated that women's participation in such groups leads to the emergence of their economic, political, social, and psychological empowerment (Eyben et al., 2008).

In addition, the literature on the positive effects of group experiential knowledge includes social support, exchange of coping strategies, and a broadened perspective through the mutual exchange of information among members (Kyrouz et al., 2004;

and Munn-Giddings and Borkman, 2005). Many of these advantages stem from members' ability to gain new perspectives on their problems due to the group's collective knowledge accumulated over time through sharing personal experiences (Munn-Giddings and McVicar, 2007).

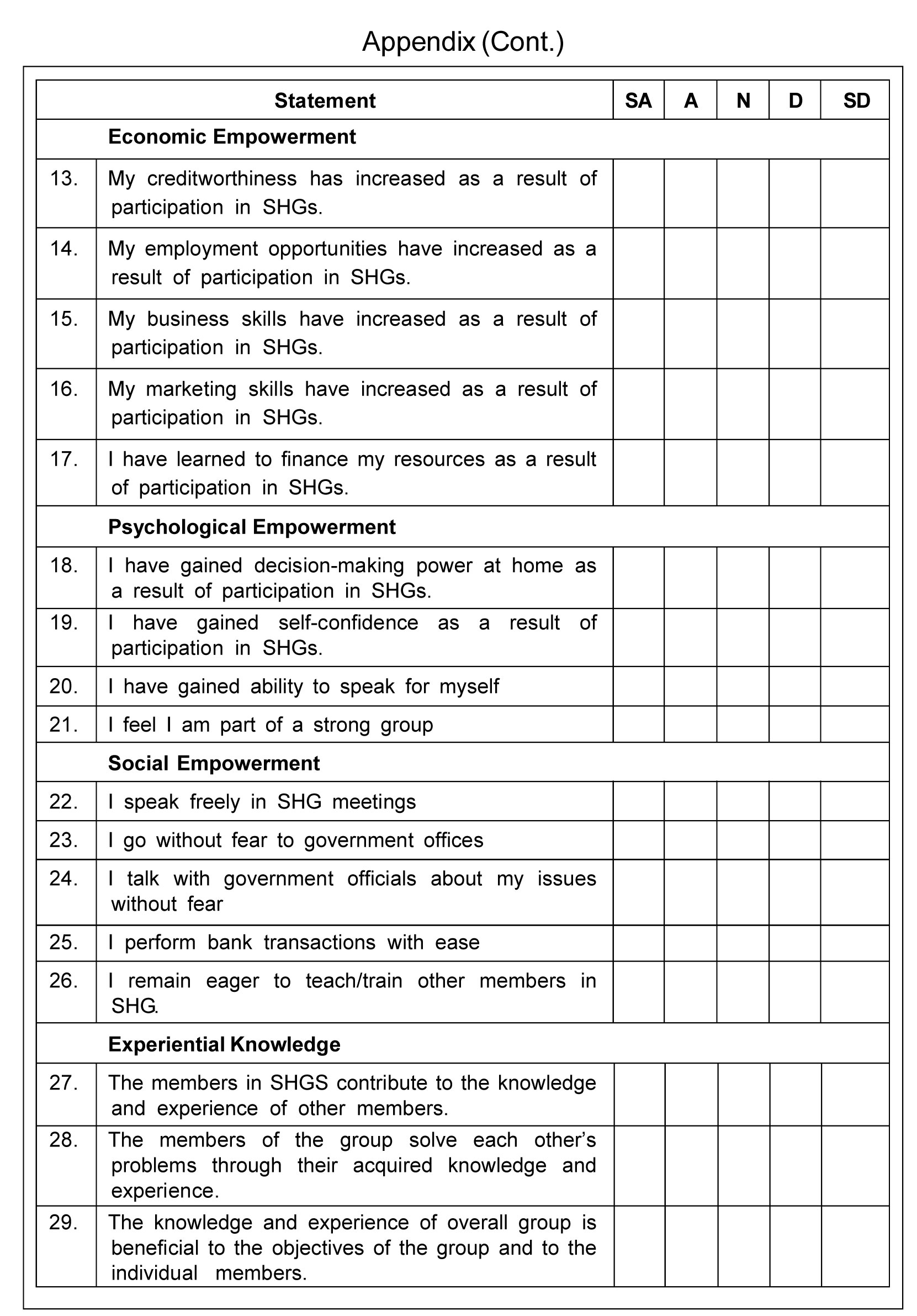

Using the conceptual framework given in Figure 1, we propose that participation in SHGs positively impacts the empowerment of the women members of SHGs. Further, we have assumed that the group's expertise/knowledge moderates the relationship between women's involvement in SHGs and their empowerment.

Based on the above, the following study hypotheses were formulated:

- H1: There is a positive relationship between women's participation in SHGs and their political empowerment.

- H2: There is a positive relationship between women's participation in SHGs and their economic empowerment.

- H3: There is a positive relationship between women's participation in SHGs and their psychological empowerment.

- H4: There is a positive relationship between women's participation in SHGs and their social empowerment.

- H5: Group's experiential knowledge moderates the positive association between women's participation in SHGs and economic empowerment.

- H6: Group's experiential knowledge moderates the positive association between women's participation in SHGs and social empowerment.

- H7: Group's experiential knowledge moderates the positive association between women's participation in SHGs and political empowerment.

- H8: Group's experiential knowledge moderates the positive association between women's participation in SHGs and psychological empowerment.

Data and Methodology

A causal design (research plan) was utilized in this study. The cause-and-effect relationship between the independent variables (women's participation in SHGs) and dependent variables (Social Empowerment; Political Empowerment; Economic Empowerment; and Psychological Empowerment) was determined. The groups' experiential knowledge moderated the relationship between women's participation in SHGs and women's empowerment. Two hundred and sixty-seven questions (functional) were employed in this inquiry. For data collection, a survey was done among women in different SHGs in the Union Territory of J&K. The study was conducted in 2022.

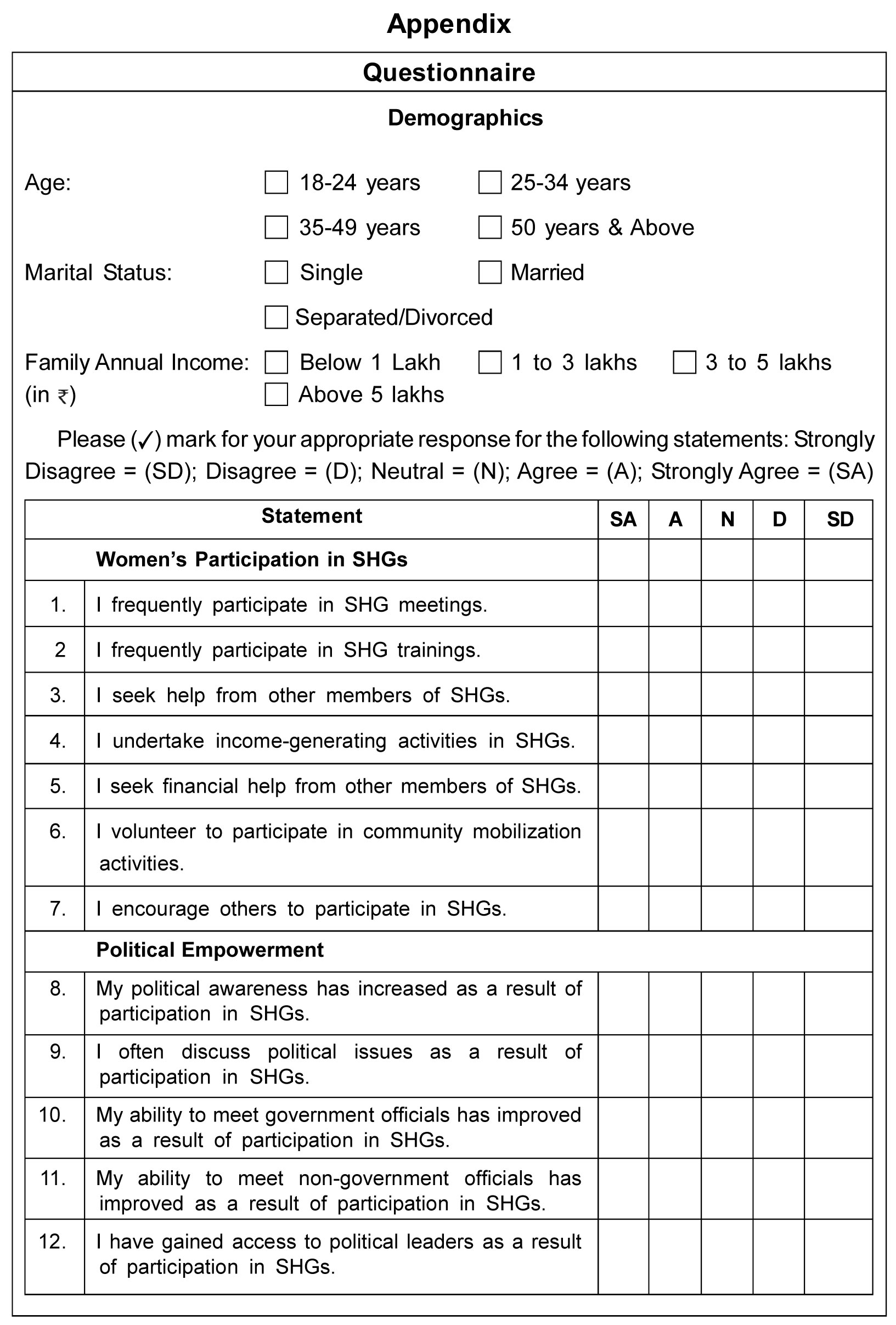

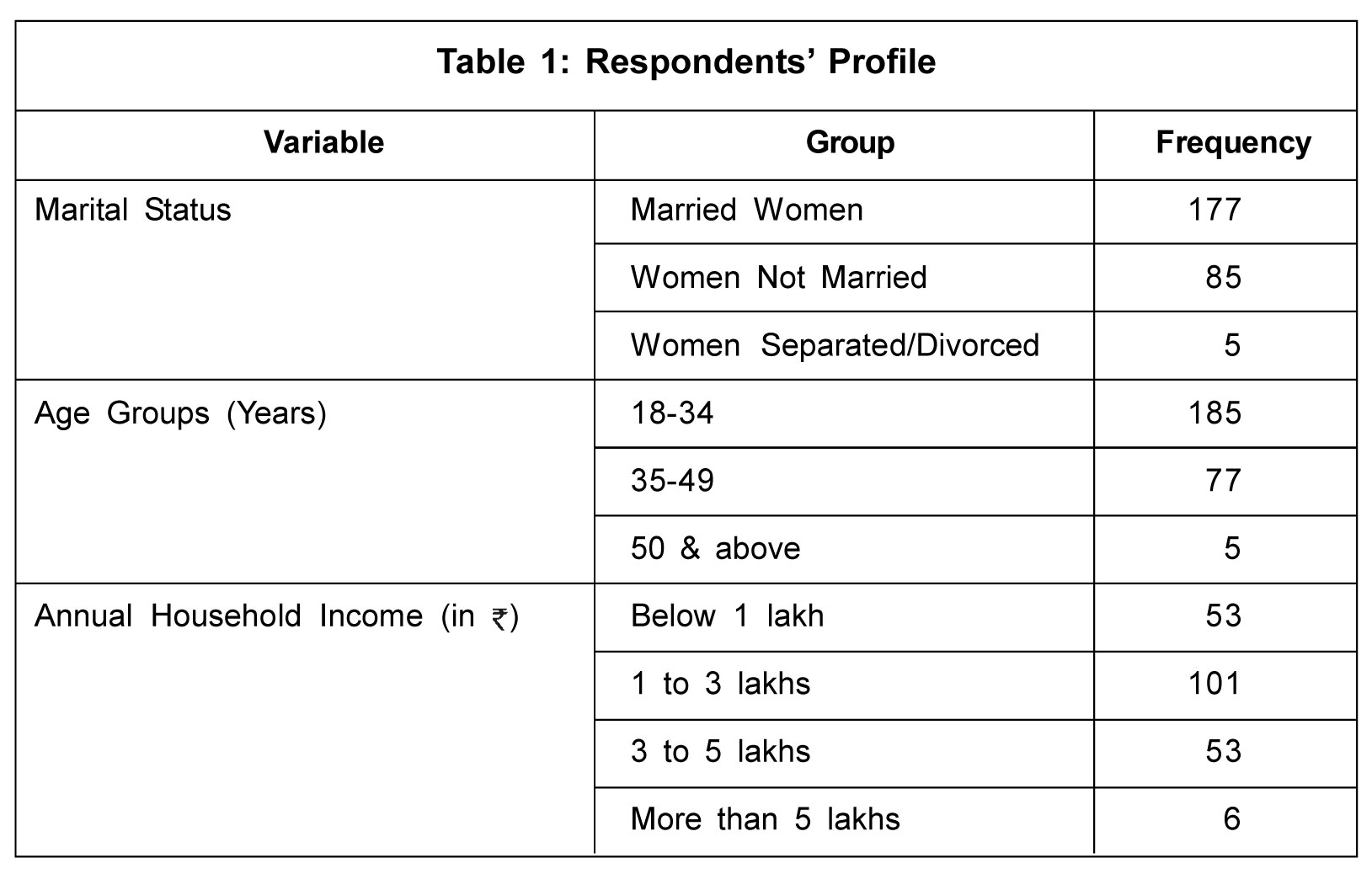

Measures (Questionnaire)

Five questions, each derived from Harika et al. (2020), were used to assess political, social and economic empowerment. Four questions, derived from Geetha and Dhanasekaran (2021), were used to assess psychological empowerment. Seven questions, derived from Nayak and Panigrahi (2020), were used to assess participation in SHGs. Three questions, from Schiff and Bargal (2000), were used to assess group's experiential knowledge (see Appendix).

Data Analysis

The association between the independent variable (women's participation in SHGs) and the dependent variables (Social Empowerment; Political Empowerment; Economic Empowerment; and Psychological Empowerment) was analyzed using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). Moreover, the experiential knowledge shared within the groups served as a moderator in the association between women's engagement in SHGs and women's increased levels of empowerment. SEM is a multivariate statistical analysis method to investigate the relationship between independent and dependent variables. It is a combination of factor analysis and multiple regression analysis. It has two steps, starting with the specification of the measurement model or confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), which essentially validates the factor structure obtained after running exploratory factor analysis (EFA); the next step is path analysis, which establishes the association between independent and dependent variables.

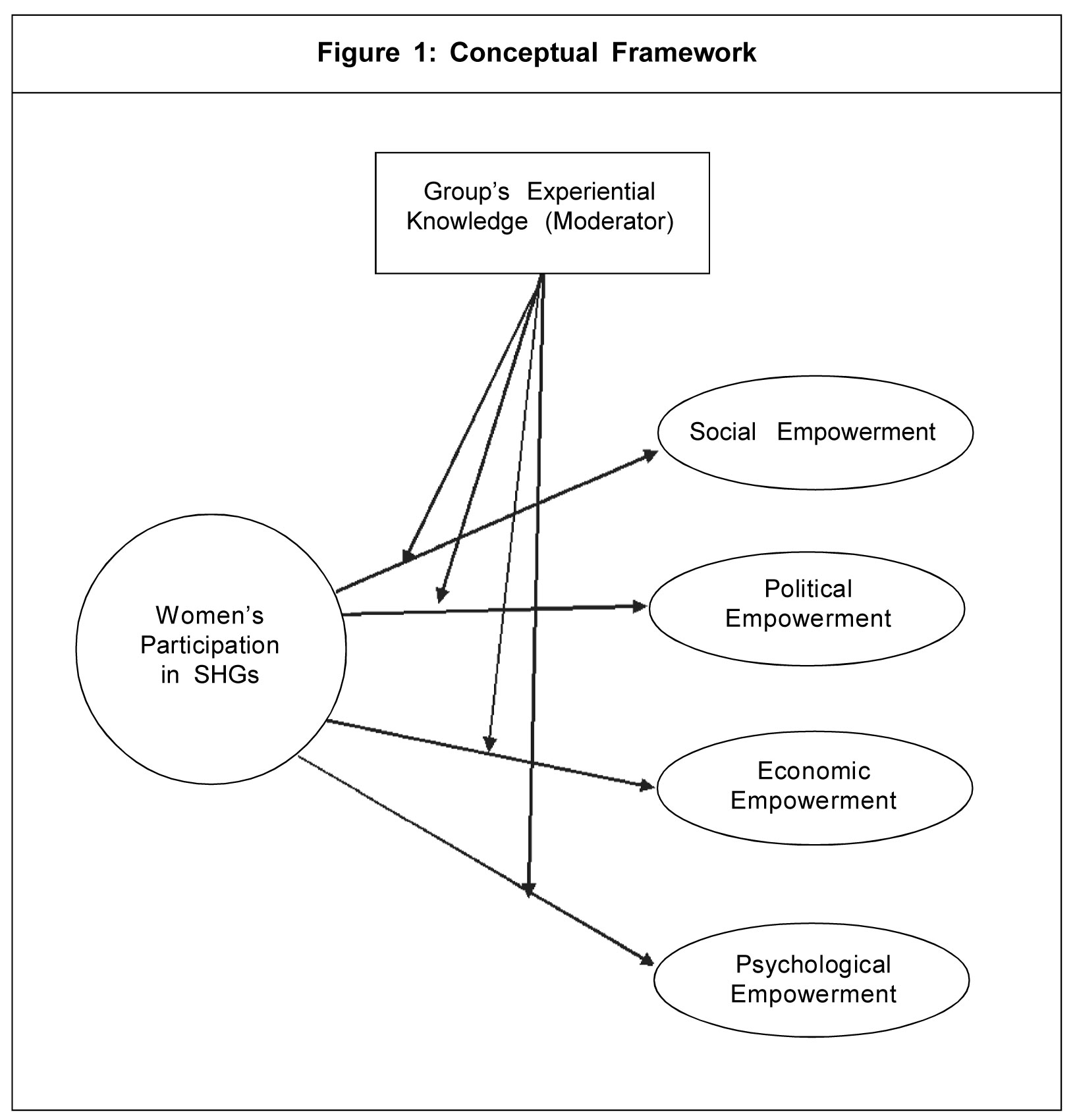

Respondent Profile

Table 1 displays the demographics of the survey participants, including their marital status, age, and annual income.

Exploratory Factor Analysis

EFA was used in SPSS 25.0 because of the scale's minor modifications to represent better the local context (Hair et al., 2006). EFA was run to establish whether the items of all the factors loaded on their particular constructs (items correlated with factors or not) or not. The results show that all the items were loaded on their respective factors without cross-loading. Cronbach's alpha was more significant than the stated figure of 0.60% regarding reliability (Hair et al., 2006). EFA findings exceeded the acceptable values for sample adequacy using both the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) and the Bartlett's test of sphericity (0.900 and 10043.413, respectively). The six variables account for 82.8%

of the total variation. Twenty-nine variables in the dataset had a loading greater than 0.50 (Hair et al., 2006).

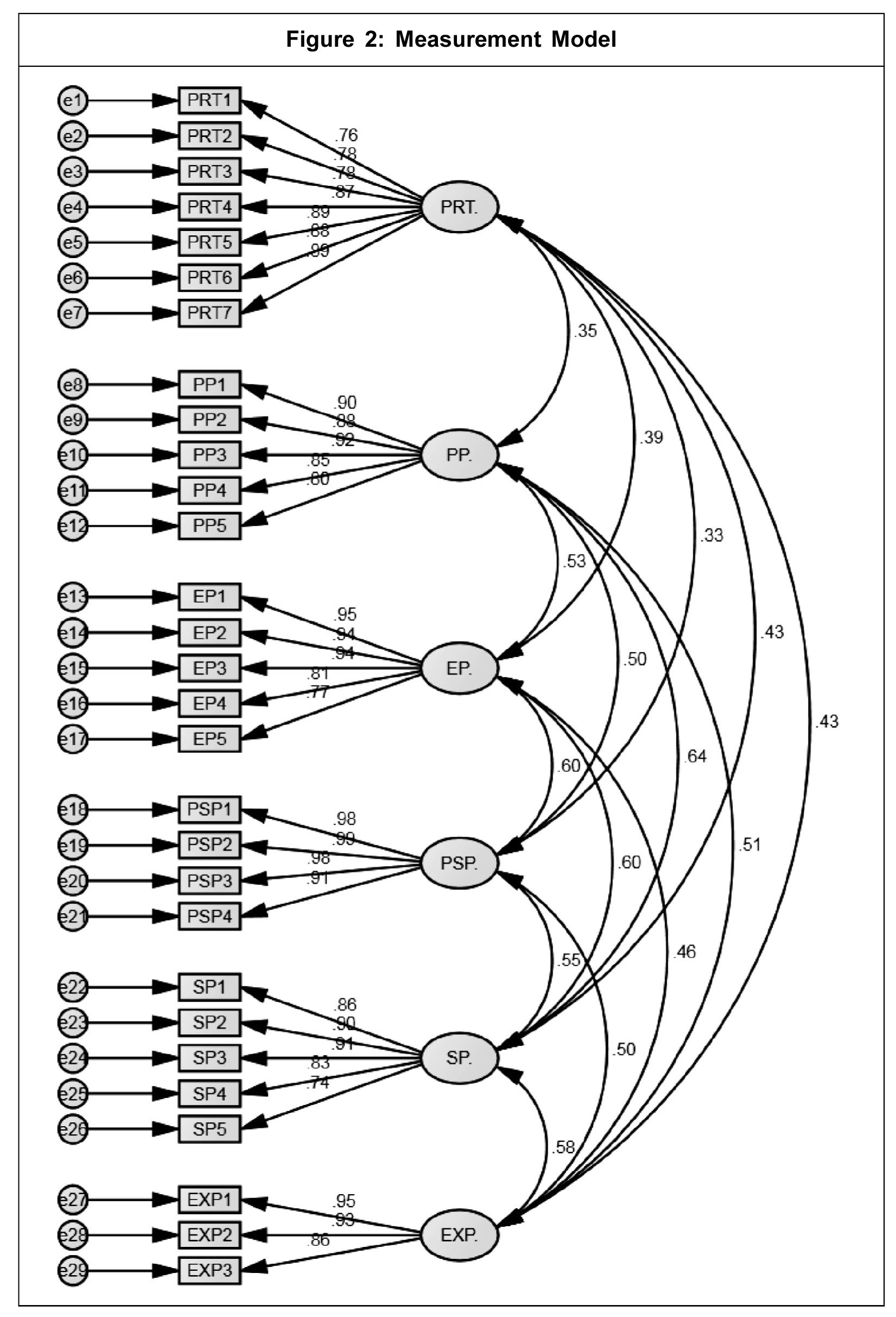

Measurement Model

After EFA was run in SPSS, CFA the measurement model (Figure 2) was generated in AMOS 25.0 to confirm the factor structure obtained from EFA. The values obtained from CFA were found to be satisfactory. Model fit values are satisfactory, as shown by the findings: CMIN/DF = 3.09; CFI = 0.928, GFI = 0.801, NFI = 0.897 and RMSEA = 0.071 (Hu and Bentler, 1999).

Reliability and Validity

The reliability of the instrument was confirmed in CFA using Composite Reliability (CR) scores, which were better than 0.60 and hence determined the instrument's dependability (Table 2). Tests for the convergent validity included using AVE scores which were more than 0.50, and standardized loadings were above 0.50 (see Table 2) (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). Analysis proved (Fornell and Larcker, 1981) discriminant validity since the correlation coefficient is smaller than the AVE square (see Table 2).

Structural Model

The final step, SEM, is the path analysis or the structural model that tests the relationship between predictor (Participation in SHG) and outcome variables (Social Empowerment; Political Empowerment; Economic Empowerment; and Psychological Empowerment). The following data show that the model is well-fitting:

CMIN/df = 3.9, GFI = 0.803, CFI = 0.909, RMSEA = 0.077, NFI = 0.888.

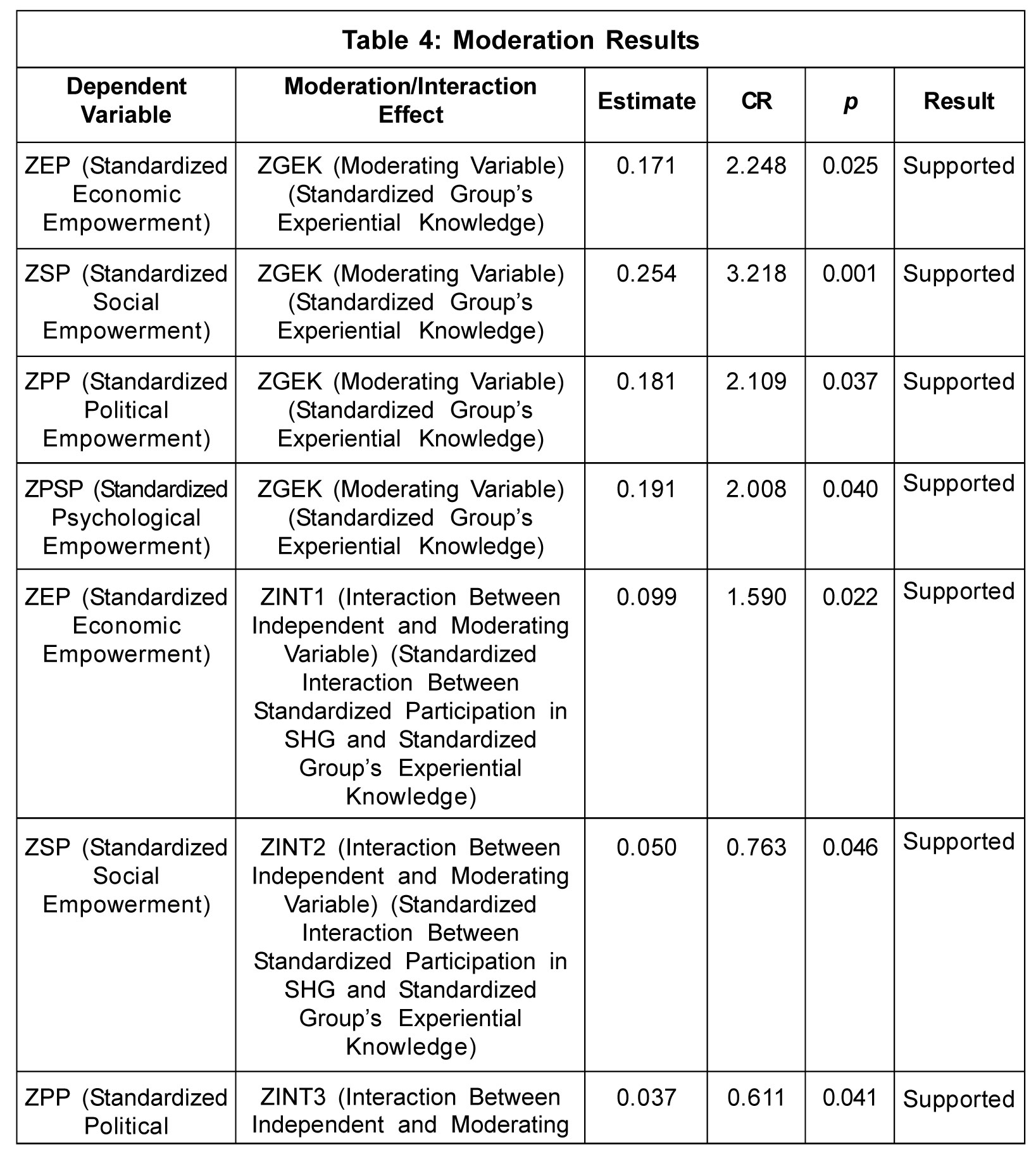

Additional data from moderation analysis are shown in Table 4. The moderation effect is analyzed by first calculating standardized scores for independent (Participation in SHG), dependent (Social Empowerment; Political Empowerment; Economic Empowerment; and Psychological Empowerment) and moderator (Group's Experiential Knowledge) variables. After that, the interaction effect was calculated using AMOS 25.0 between the moderator and independent variable. The effect of interaction (standardized interaction between independent and moderator variables) was tested on the dependent variable. Table 4 shows the effect of the moderator on dependent variables and the effect of interaction on dependent variables. The estimate of the interaction effect shows the moderation, and the subsequent p-value is also illustrated in Table 4

Hence, hypothesis H5 is supported as the group's experiential knowledge moderates the positive association between women's participation in SHGs and economic empowerment (b = 0.099; p-value is less than 0.005). H6 is supported as the group's experiential knowledge moderates the positive association between women's participation in SHGs and social empowerment (b = 0.050; p-value is less than 0.005). H7 is supported as the group's experiential knowledge moderates the positive association between women's participation in SHGs and political empowerment (b = 0.037; p-value is less than 0.005). H8 is supported as the group's experiential knowledge moderates the positive association between women's participation in SHGs and psychological empowerment

(b = 0.050; p-value is less than 0.005).

Implications

Theoretically and practically, this study has enormous consequences. The paper establishes a novel framework within which scholars may analyze women's empowerment through its determinants and the inclusion of a moderator. Considering the potential causal processes, these results may offer us further practical information for enhancing women empowerment. The study may result in developing other programs and packages to assist women in developing a more positive attitude toward life and ultimately empower them on multiple fronts. This study confirms that programs such as SHGs, which concentrate on revenue creation and improving women's lives through different measures, have the combined benefit of leading to a better economic status and being the main effectual component in empowering women. More independence and significant changes in societal views also contribute to the empowerment of women. In terms of application, this work helps by offering trustworthy evidence to policymakers. The primary purpose of SHG program is social empowerment and revenue generation for women, as also indicated by the results. Increased confidence in dealing with financial crises and saving independently is also empowering.

Social attitudes and a quest for greater autonomy are crucial in empowering SHG members. Members may engage in activities such as educating SHG associates about women's rights (permissible, political, and societal), raising public attentiveness about the importance of positive attitudes toward women, and exposing women to available government programs and opportunities. Education, greater political engagement, and improved communication influence the long-term empowering process. Finally, this work developed a moderated model for the connection between women's empowerment and their participation in SHGs. Members of these groups see experiential knowledge provided via personal experiences and ideas as a highly valued characteristic of these communities. The leader of these groups can also guide individuals and assist them in resolving or alleviating their difficulties. This suggests that women should interact with other members to gain more knowledge and expertise, which would help them in their endeavors.

Conclusion

The SEM study confirms the preceding four assumptions. Women's participation in SHGs positively influences political empowerment (b = 0.38; R2 = 0.15), which is statistically significant and supports H1. This study's findings align with those of earlier investigations (Jakimow and Kilby, 2006; and Nayak and Panigrahi, 2020). This exemplifies the significant impact that SHGs have on the advancement of women's political visibility and influence. By participating in SHGs, women increase the opportunities available to them to speak up, participate in decision-making processes, and express their rights, strengthening their political standing.

Women's participation in SHGs positively influences economic empowerment (b = 0.40; R2 = 0.16), which is statistically significant and supports H2. Previous studies reported similar findings (Jakimow and Kilby, 2006; and Nayak and Panigrahi, 2020). This shows that participation in these groups can give women vital economic skills and opportunities, ranging from financial management to activities that generate revenue. These skills and possibilities can be obtained through involvement in these groups. This is consistent with earlier research highlighting the significant role that SHGs play in helping women achieve economic independence.

Women's participation in SHGs also affirmatively influences psychological empowerment (b = 0.37; R2 = 0.13), which is statistically significant and supports H3. The findings of this study are in congruence with some of the earlier studies (Zimmerman, 1990; Jakimow and Kilby, 2006; and Nayak and Panigrahi, 2020). SHGs provide a caring environment that boosts women's self-esteem, self-efficacy, and general psychological wellness. This link showed the lowest beta value of all the relationships studied, but it was still statistically significant, showing that SHGs provide a nurturing environment that boosts women's self-esteem.

Lastly, women's participation in SHGs positively influences social empowerment

(b = 0.37; R2 = 0.13), which is statistically significant and supports H4. These findings match the results of earlier works (Jakimow and Kilby, 2006). This demonstrates that women can improve their social status and build good relationships within and outside their community by participating in SHGs, which offer them a platform.

The substantially higher influence on social empowerment may suggest that the collective power of SHGs particularly lends itself to developing women's social relationships and networks. This is true, even though all types of empowerments are necessary in their own right. On the other hand, the significantly lower beta for psychological empowerment implies that although SHGs have an excellent impact on women's psychological wellbeing, other elements not recorded in this study might also play a significant role. These other aspects should have been taken into account in this study. The data presented here provide a complete knowledge of SHGs' role in empowering women across various elements of their lives. This means that women's active participation and involvement in SHGs is vital to achieving their empowerment at all four levels. As a part of SHG, women reported feeling more competent to speak in public, such as extended family units, authorities, and society leaders.

Moreover, group support aided them in making meaningful choices and enacting good changes in their lives. Research also shows that women's participation in SHGs gave them confidence in handling cash and making better monetary decisions. Women also claimed that their spouses' and community members' gradual acceptance due to their association with SHGs bolstered their political activities. This study adds to the literature on the benefits of women's involvement in SHGs.

In addition, H5, H6, H7 and H8 also supported that the group's experiential knowledge moderates the relationship between women's participation in SHGs and its four outcomes (political, social, psychological and economic empowerment).

According to the findings, the group's experiential knowledge does, in fact, moderate the correlations between women's engagement in SHGs and their economic, social, political, and psychological empowerment. The research validated these four hypotheses. The findings demonstrate that when women join SHGs and obtain experiential knowledge from their peers, they are better positioned to handle economic problems, enhance their financial literacy, and assert their economic independence. The work also suggests that experiential learning within SHGs has the potential to both encourage the development of more robust social networks and boost psychological wellbeing. The combined effect of knowledge exchange and the sense of belonging that comes from being a part of a supportive group may be responsible for this phenomenon. The findings also show that the shared experiences and insights from SHGs can equip women with the skills and confidence necessary to participate more actively in political issues. The moderating effects discovered in this study shed light on the crucial part played by the exchange of firsthand experience within small group settings. Women are collectively becoming more empowered in various areas due to their participation in these groups and sharing their experiences. The study highlights how important it is to cultivate a setting in which the members of the group feel comfortable sharing their experiences and lessons learned from one another. This means that active engagement of women with other members of the group is vital for their improvement. This is because the interaction between members leads to knowledge exchange and enhanced proficiency, ultimately empowering them.

Future Scope: In future studies, both genders may be included. A more significant number of participants may be used in future studies. Additional research could be done in various parts of India, as well as in big cities and rural areas. The mediation and moderating impacts of several variables, such as social status, income, government assistance, and demographic traits, should be studied in future research. Longitudinal and qualitative studies may be helpful to explain any correlations in causation among variables and expand knowledge of their connections, because the current research was indeed a cross-sectional study that overlooked causal relationships between study variables. NGOs and other non-profit groups that serve people in need can be studied.

References

- Aruna M and Jyothirmayi M R (2011), "The Role of Microfinance in Women Empowerment: A Study on the SHG Bank Linkage Program in Hyderabad (Andhra Pradesh)", Indian Journal of Commerce and Management Studies, Vol. 2, No. 4, pp. 77-95, Educational Research Multimedia & Publications, India.

- Borkman T (1976), "Experiential Knowledge: A New Concept for the Analysis of Self-Help Groups", Social Service Review, Vol. 50, No. 3, pp. 445-456.

- Borkman T (1990), "Self-Help Groups at the Turning Point: Emerging Egalitarian Alliances with the Formal Health Care System?", American Journal of Community Psychology, Vol. 18, No. 2, pp. 321-332.

- Brody C, Hoop T D, Vojtkova M et al. (2017), "Can Self-Help Group Programs Improve Women's Empowerment? A Systematic Review", Journal of Development Effectiveness, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 15-40.

- Chapin F S (1928), "A Quantitative Scale for Rating the Home and Social Environment of Middle-Class Families in an Urban Community: A First Approximation to the Measurement of Socioeconomic Status", Journal of Educational Psychology, Vol. 19, No. 2, p. 99.

- Chatterjee S, Gupta S D and Upadhyay P (2018), "Empowering Women and Stimulating Development at the Bottom of the Pyramid Through Micro-Entrepreneurship", Management Decision, Vol. 56, No. 1, pp. 160-174.

- Cohen D K and Karim S M (2022), "Does More Equality for Women Mean Less War? Rethinking Sex and Gender Inequality and Political Violence", International Organisation, Vol. 76, No. 2, pp. 414-444.

- Dahal S (2014), "A Study of Women's Self-Help Groups and the Impact of SHG Participation on Women Empowerment and Livelihood in Lamachaur Village of Nepal", Master's Thesis, Norwegian University of Life Sciences, As, Norway.

- De Hoop T, Van Kempen L, Linssen R and Van Eerdewijk A (2014), "Women's Autonomy and Subjective Well-Being: How Gender Norms Shape the Impact of Self-Help Groups in Odisha, India", Feminist Economics, Vol. 20, No. 3, pp. 103-135.

- Dubey S, Dwivedi A, Agarwal N and Singh C K (2021), "Role of Microfinance and Self-Help Group in Women's Financial, Behavioral and Psychological Empowerment", Indian Journal of Economics and Business, Vol. 20, No. 4, pp. 1829-1838.

- Duflo E (2012), "Women Empowerment and Economic Development", Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. 50, No. 4, pp. 1051-1079.

- Eyben R, Kabeer N and Cornwall A (2008), Conceptualising Empowerment and the Implications for Pro-Poor Growth, DAC Poverty Network by the Institute of Development Studies, Brighton.

- Fornell C and Larcker D F (1981), Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 18, No. 3, pp. 382-388.

- Geetha G and Dhanasekaran S (2021), "Role of Self Help Groups in Women Empowerment - A Study with Reference to Vellore District", NVEO-Natural Volatiles and Essential Oils Journal, Vol. 8, No. 4, pp. 3156-3167.

- Hair J, Tatham R, Anderson R and Black W (2006), Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th Edition, Pearson Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ.

- Harika K, Raviteja K and Nagaraju V (2020), "Women Empowerment Through Self-Help Groups (SHGs) in Three Dimensions: An Empirical Study of Rural Andhra Pradesh", International Journal of Social Science, Vol. 9, No. 4, pp. 263-271.

- Hu L T and Bentler P M (1999), "Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives", Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, Vol. 6, No. 1, pp. 1-55.

- Jakimow T and Kilby P (2006), "Empowering Women: A Critique of the Blueprint for Self-Help Groups in India", Indian Journal of Gender Studies, Vol. 13, No. 3, pp. 375-400.

- Kabeer N (2001), "Conflicts Over Credit: Re-Evaluating the Empowerment Potential of Loans to Women in Rural Bangladesh", World Development, Vol. 29, No. 1, pp. 63-84.

- Kabeer N (2008), Mainstreaming Gender in Social Protection for the Informal Economy, Commonwealth Secretariat.

- Kabeer N (2010), "Women's Empowerment, Development Interventions and the Management of Information Flows", ids Bulletin, Vol. 41, No. 6, pp. 105-113.

- Kabeer N (2011), "Between Affiliation and Autonomy: Navigating Pathways of Women's Empowerment and Gender Justice in Rural Bangladesh", Development and Change, Vol. 42, No. 2, pp. 499-528.

- Kandpal V (2022), "Socio-Economic Development Through Self-Help Groups in Rural India - A Qualitative Study", Qualitative Research in Financial Markets, Vol. 14, No. 5, pp. 621-636.

- Kennedy M, Humphreys K and Borkman T (1994), "The Naturalistic Paradigm as an Approach to Research with Mutual-Help Groups", In Understanding the Self-Help Organization: Frameworks and Findings, pp. 172-189. https://sk.sagepub.com/books/understanding-the-self-help-organization/n10.xml

- Khan S T, Bhat M A and Sangmi M U D (2023), "Impact of Microfinance on Economic, Social, Political and Psychological Empowerment: Evidence from Women's Self-Help Groups in Kashmir Valley, India", FIIB Business Review, Vol. 12, No. 1, pp. 58-73.

- Kilby P (2011), NGOs in India: The Challenges of Women's Empowerment and Accountability, 1st Edition, p. 148, Routledge.

- Kim J, Ferrari G, Abramsky T et al. (2009), "Assessing the Incremental Effects of Combining Economic and Health Interventions: IMAGE Study in South Africa", Bulletin of the World Health Organisation, Vol. 87, pp. 824-832.

- Kotte R (2019), "Women Empowerment Through Self Help Groups - A Study of Telangana", International Journal of Multidisciplinary Educational Research, Vol. 10, Nos. 6(5), pp. 126-132.

- Kyrouz E, Humphreys K and Loomis C (2004), "A Review of Research on the Effectiveness of Self-Help Mutual Aid Groups", in B J White and E J Madara (Eds.), The Self-Help Group Sourcebook, 7th Edition, pp.71-85, Cedar Knolls Publishers.

- Madhok S (2013), Action, Agency, Coercion: Reformatting Agency for Oppressive Contexts, pp. 102-121, Palgrave Macmillan, London, UK.

- Mathrani V and Periodi V (2006), "The Sangha Mane: The Translation of an Internal Need into a Physical Space", Indian Journal of Gender Studies, Vol. 13, No. 3, pp. 317-349.

- Munn-Giddings C and Borkman T (2005), "Self-Help/Mutual Aid as Part of the Psychosocial Paradigm", in S Ramon and J Williams (Eds.), Mental Health at the Crossroads: The Promise of the Psychosocial Approach, pp. 137-154, Ashgate Press, Aldershot, Hampshire, England.

- Munn-Giddings C and McVicar A (2007), "Self-Help Groups as Mutual Support: What Do Carers Value?", Health & Social Care in the Community, Vol. 15, No. 1, pp. 26-34.

- Nayak A K (2015), "Developing Social Capital Through Self-Help Groups", Indore Management Journal, Vol. 7, No. 1, pp. 18-24.

- Nayak A K and Panigrahi P K (2020), "Participation in Self-Help Groups and Empowerment of Women: A Structural Model Analysis", The Journal of Developing Areas, Vol. 54, No. 1, pp. 19-37.

- Nichols C E (2022), "The Politics of Mobility and Empowerment: The Case of Self-Help Groups in India", Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, Vol. 47, No. 2, pp. 470-483.

- Parker R N (1983), "Measuring Social Participation", American Sociological Review, Vol. 48, No. 6, pp. 864-873.

- Pattenden O (2018), The Way Forward? in Taking Care of the Future, pp. 389-408, Palgrave Macmillan, Cham.

- Pronyk P M, Hargreaves J R, Kim J C et al. (2006), "Effect of a Structural Intervention for the Prevention of Intimate-Partner Violence and HIV in Rural South Africa: A Cluster Randomised Trial", Lancet, Vol. 368, No. 9551, pp. 1973-1983. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69744-4

- Quisumbing A, Meinzen-Dick R and Malapit H (2022), "Women's Empowerment and Gender Equality in South Asian Agriculture: Measuring Progress Using the Project-Level Women's Empowerment in Agriculture Index (pro-WEAI) in Bangladesh and India", World Development, Vol. 151, No. 1, 105396. DOI:10.1016/j.worlddev.2021. 105396.

- Rai V and Shrivastava M (2021), "Microfinancial Drivers of Women Empowerment: Do Self-Help Group Membership and Family Size Moderate the Relation?", The Indian Economic Journal, Vol. 69, No. 1, pp. 140-162.

- Ramachandar L and Pelto P J (2009), "Self-Help Groups in Bellary: Microfinance and Women's Empowerment", Journal of Family Welfare, Vol. 55, No. 2, pp. 1-16.

- Rodriguez Z (2022), "The Power of Employment: Effects of India's Employment Guarantee on Women Empowerment", World Development, Vol. 152, No. C, 105803. DOI: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105803

- Sahu L and Singh S K (2012), "A Qualitative Study on the Role of Self-Help Groups in Women Empowerment in Rural Pondicherry, India", National Journal of Community Medicine, Vol. 3, No. 3, pp. 473-479.

- Sato N, Shimamura Y and Lastarria-Cornhiel S (2022), "The Effects of Women's Self-Help Group Participation on Domestic Violence in Andhra Pradesh, India", Feminist Economics, Vol. 28, No. 1, pp. 29-55.

- Schiff M and Bargal D (2000), "Helping Characteristics of Self-Help and Support Groups: Their Contribution to Participants' Subjective Well-Being", Small Group Research, Vol. 31, No. 3, pp. 275-304.

- Schubert M A and Borkman T (1994), "Identifying the Experiential Knowledge Developed within a Self-Help Group", in TJ Powell (Ed.), Understanding the Self-Help Organisation: Frameworks and Findings, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks.

- Sen A (2001), "The Many Faces of Gender Inequality", New Republic, Vol. 18, No. 22, pp. 35-39.

- Sharma A (2008), Logics of Empowerment: Development, Gender, and Governance in Neoliberal India, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, MN.

- Shireesha E (2019), "Empowerment of Women Through Self-Help Groups", International Journal of Scientific Development and Research (IJSDR), Vol. 4, No. 12, pp. 13-16.

- Singh P, Tabe T and Martin T (2022), "The Role of Women in Community Resilience to Climate Change: A Case Study of an Indigenous Fijian Community", Women's Studies International Forum, Vol. 90, p. 102550, Pergamon.

- Siwach G, Paul S and de Hoop T (2022), "Economies of Scale of Large-Scale International Development Interventions: Evidence from Self-Help Groups in India", World Development, Vol. 153, No. C, 105839. DOI: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2022.105839

- Stenersen M R, Thomas K, Struble C et al. (2022), "The Impact of Self-Help Groups on Successful Substance Use Treatment Completion for Opioid Use: An Intersectional Analysis of Race/Ethnicity and Sex", Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, Vol. 136, 108662. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108662

- Zimmerman M A (1990), "Taking Aim on Empowerment Research: On the Distinction Between Individual and Psychological Conceptions", American Journal of Community Psychology, Vol. 18, No. 1, pp. 169-177.

- Zulfiqar G M (2022), "Inequality Regimes, Patriarchal Connectivity, and the Elusive Right to Own Land for Women in Pakistan", Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 177, No. 4, pp. 799-811.