Mar'23

The IUP Journal of Entrepreneurship Development

Archives

Antecedents of Entrepreneurial Willingness Among University Students: An Empirical Study

Shubham Garg

Research Scholar, Haryana School of Business, Guru Jambheshwar University of Science and Technology, Hisar, Haryana, India; and is the corresponding author. E-mail: Shubhamgarg1230@gmail.com

Parveen Kumar

Research Scholar, Haryana School of Business, Guru Jambheshwar University of Science and Technology, Hisar, Haryana, India. E-mail: pkpabriya@gmail.com

Sanjeev Kumar

Professor, Haryana School of Business, Guru Jambheshwar University of Science and Technology, Hisar, Haryana, India. E-mail: sanjeev.aseem@gmail.com

Entrepreneurship is a powerful tool to reduce unemployment. Hence, educational institutions run many entrepreneurial programs and students too participate in them, which in turn enhance their employability. The study investigates the entrepreneurial willingness of university students across all streams. It particularly analyzes the willingness of 218 respondents on the basis of gender, field of study and family background, using independent sample t-test (2 dependent groups) and one-way ANOVA, Welch test and post-hoc and parametric test. The findings show that female students have a stronger willingness to take up entrepreneurship compared to male students. As far as education streams are concerned, it is found that commerce students have higher entrepreneurial willingness in comparison to others. Family business ownership also has a positive influence on students' willingness to take up entrepreneurship.

Introduction

Production is one of the foremost economic activities that drive the economy. The facilitating attributes and conditions required for production are known as factors of production, namely, land, labor, capital and entrepreneurship. It is entrepreneurship that combines all the other factors for economic development (Fernando, 2022). Earlier, it was considered as a part of the production function, but considering its increased importance, entrepreneurship has become a separate domain.

According to Cole (1959), "Entrepreneurship is the voluntary activity of an individual or a group of associated individuals, undertaken to initiate, maintain or enlarge profit through the production or distribution of economic goods and services1." In the literature, entrepreneurship has been defined using two approaches, i.e., Functional and Indicative (Casson, 2003). In this study, we use the Indicative approach to define entrepreneur and entrepreneurship. As per the Indicative approach, entrepreneurship is linked with psychological traits like creativity, risk-taking ability, etc. In today's world, dynamism, creativity, innovation and risk-taking abilities are the fundamental requirements for entrepreneurship (Kumar, 2013). These attributes are known as psychological traits of entrepreneurship. Thus, a person who has these qualities or attributes is known as an entrepreneur (Hirsich et al., 2005). The requisite attributes for entrepreneurship can be acquired through technical training and education. Entrepreneurship education has been defined as a collection of formalized teachings that educate anyone interested in business creation (Wei et al., 2019). Formal education can help the students in the journey-starting from idea generation to setting up a business and future growth of the venture. The goal of entrepreneurship education is to develop creative abilities that can be used in situations, practices, and settings that favor innovation (Binks et al., 2006; and Gundry

et al., 2014). Entrepreneurial education is distinct from other forms of education because in any entrepreneurial education program, it is necessary to blend the theoretical concepts with practical implementation. On the other hand, it necessitates strong commitment, determination, readiness, and willingness on the part of the students (Mani, 2015). The Indian government considers entrepreneurship education as an important vehicle to promote entrepreneurial mindset and attitude among students. Hence, the government has included required entrepreneurship courses in program curriculum. The regional institutions have introduced specialized courses; however, it remains to be seen whether these courses are able to produce long-lasting beneficial changes among students (Chakraborty and Singh, 2019).

Willingness is described as the quality or state of being prepared to achieve something. Entrepreneurial willingness refers to the readiness to start as an entrepreneur after considering available career choices (Kumar, 2013). Willingness to start as an entrepreneur refers to the preference of a person, after evaluating the available employment avenues, against being unemployed in a given situation. When entrepreneurship is seen as the best career choice, the willingness to start a new venture is very high, thus showing that self-employment and willingness both have a positive relationship (Praag and Ophem, 1995). Although both have positive relationship, still the ultimate choice depends on individual preferences and perceived benefits of available options, i.e., other than entrepreneurship.

Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

The available literature has been divided into different subheads according to the hypotheses of the study.

Gender-Based Differences and Entrepreneurial Willingness

Women-based enterprises are on the rise, still they are less in number compared to male entrepreneurs (Kamarkar and Chhabra, 2016). Entrepreneurial willingness depends on many factors, including motivation, career choice evaluation, family background and desire for doing something new. In middle income countries like India, only 25% women are self-employed compared to male entrepreneurs. Male students tend to have psychological inclination towards entrepreneurship. Lack of experience and exposure seems to be the reason for the absence of positive outlook and intention towards entrepreneurship among female students (Dabic et al., 2012). Desire for independence is less among female students than male students (Strobl et al., 2012). The findings prove that female students are less inclined than male students to establish their own business. Females are less confident, more tense, reluctant, and concerned about entrepreneurship. They are supported more by their family due to significant gender differences in perceived feasibility and desirability (Dabic et al., 2012). A study on entrepreneurship reveals that self-efficacy is one of the significant factors that affect entrepreneurial intention and willingness. Generally, women are said to have lower level of self-efficacy in relation to matters like money management, problem-solving and quantitative aptitude (Elliott et al., 2020). Because of the above factors, females may have less entrepreneurial interest as compared to males. On the basis of the above discussion, the following hypothesis has been framed:

H1: Male students have more willingness towards entrepreneurship than female students.

Entrepreneurship and Family Business Background

Family plays an important role in shaping the entrepreneurial mindset and parents are seen as role models (Georgescu and Herman, 2020). As per Social Learning Theory, role models usually act as reference in the learning process (Bandura and Walters, 1977). Entrepreneurial environment of the family helps in the development of self-efficacy in budding entrepreneurial mind. Role models offer opportunities and give young ones practical training to handle pressure in such a way that they can acquire entrepreneurial skills, which helps increase their entrepreneurial willingness (Bosma et al., 2012). Students coming from a business family background develop interest in business-related activities from a very early age. Family support in their learning process creates a positive outlook towards entrepreneurship and risk-taking ability and they are more inclined to start a new venture or increase the scale of existing one (Krueger and Carsud, 1993). It will increase their self-efficacy and help in grooming their entrepreneurial personality (Bosma et al., 2012). All the family members cannot equally motivate the younger family members in their career choice (Aldrich and Cliff, 2003). Thus, learning from family and real experiences of participating in family business activities helps the next generation for a business startup career (Kim et al., 2006). When parents act as mentors and practically guide the new generation and increase their awareness of business issues as well as their critical decision-making capacity, then they can handle contingent situations faced by business (Auken et al., 2006). It boosts their confidence and helps overcome fear with regard to entrepreneurship. The literature review revealed very limited consideration of the influence of family businesses upon the entrepreneurial willingness of Gen Z students. The current paper aims to fill this knowledge gap by investigating the influence of family business background upon the entrepreneurial willingness of students. Existing literature states that parental business model affects the younger generation in a positive way. The business knowledge of a family member gives real and unique experience to the others members. Students who have entrepreneurial exposure in their family setting are more likely to see entrepreneurship as a viable career choice and they also have commitment towards their family business (Peterman and Kennedy, 2003). In this background, we formulate the following hypothesis:

H2: Students who have family business background have more entrepreneurial willingness than those with non-family business background.

Field of Education and Entrepreneurial Willingness

Education has a significant impact on the attitude and mindset of the learner, and when it comes to entrepreneurship, the importance of entrepreneurial education has been well documented in previous studies (Wang and Wong, 2004; Wu and Wu, 2008; and Turker and Selcuk, 2009). When we analyze the competencies of business students versus non-business students, it is found that entrepreneurial orientation is much higher in those students who pursue business stream. The term entrepreneurial education refers to the development of independent ideas and the acquisition of the skills and abilities necessary to implement these ideas (Lindner, 2018). Emancipatory approaches to entrepreneurship education emphasize its social and pedagogical relevance for society (Jonsdottir, 2015). The curriculum of business education is certainly helpful in developing entrepreneurial orientation and willingness among the students. Business education develops a management outlook among the learners, which further strengthens their ability to play the role of an entrepreneur with efficacy. Moreover, it is observed that in most of the educational courses, entrepreneurship education program is a part and parcel of the content taught to the students (Lindner, 2018). Entrepreneurship requires unique traits, and business education can trigger and support the process of developing these traits in oneself. Developing stronger entrepreneurs with a value orientation for a sustainable society is a common objective of entrepreneurship education (Ubong, 2017). Future entrepreneurs are all in schools right now, and what they learn and how willingly they participate will be determined by the value-based education they are imparted. On the basis of the above discussion, the following hypothesis has been framed:

H3: Business students have more entrepreneurial willingness than non-business students.

Data and Methodology

The sample for the study consists of 218 students from different universities in Haryana. According to the latest data from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), Haryana has the highest unemployment rate of 26.7%, followed by Rajasthan and Jammu and Kashmir, and Chhattisgarh2 has the lowest rate of 0.6%. As universities are the pillars of education and decide the profession or entrepreneurial path of the students and build entrepreneurial skills in students, the current study mainly focuses on university students (i.e., those in the final year of their graduation and postgraduation courses). The students have been divided into two categories: those who have attended entrepreneurship education programs organized by their universities and departments and those who have not attended such programs.

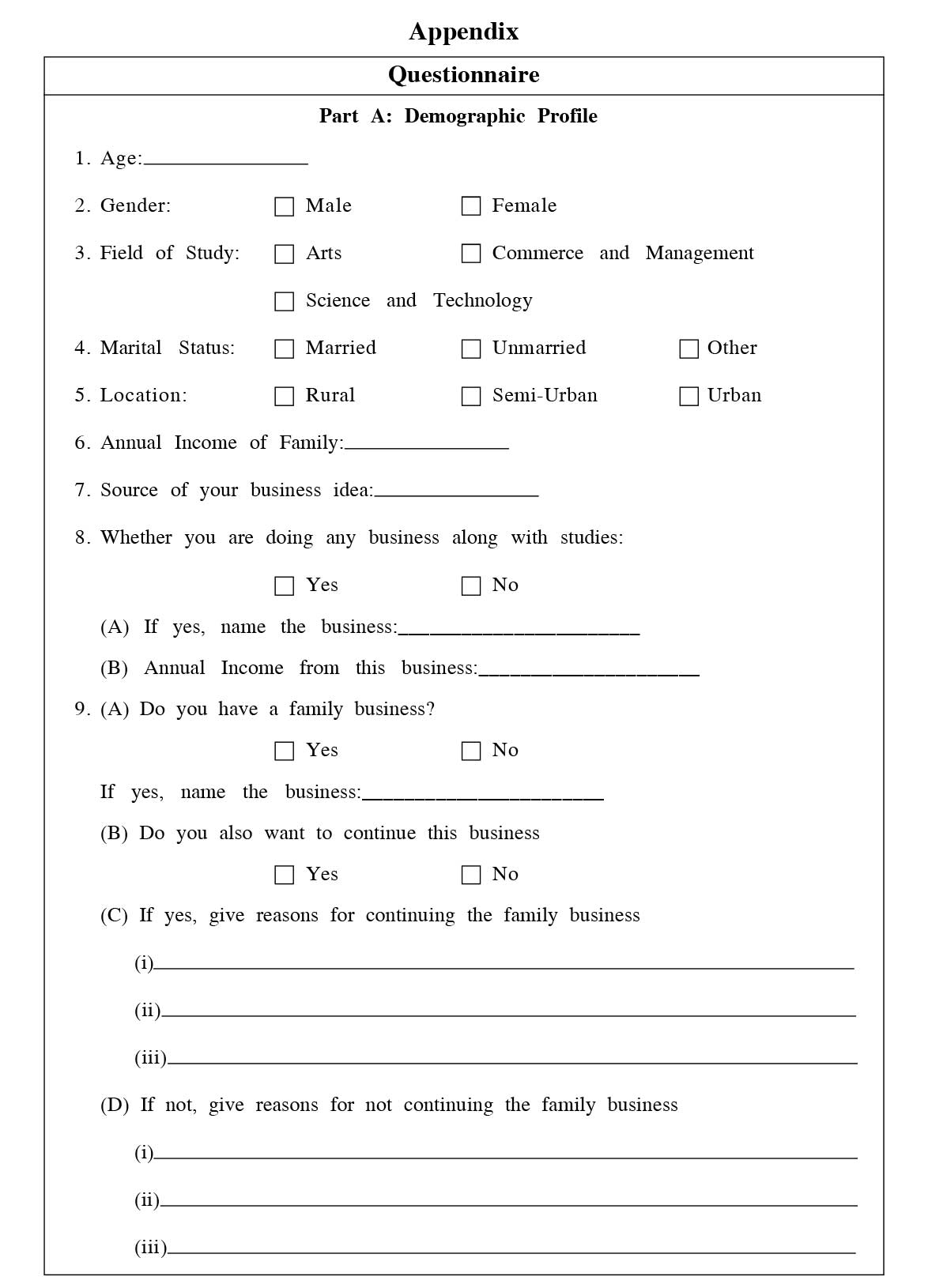

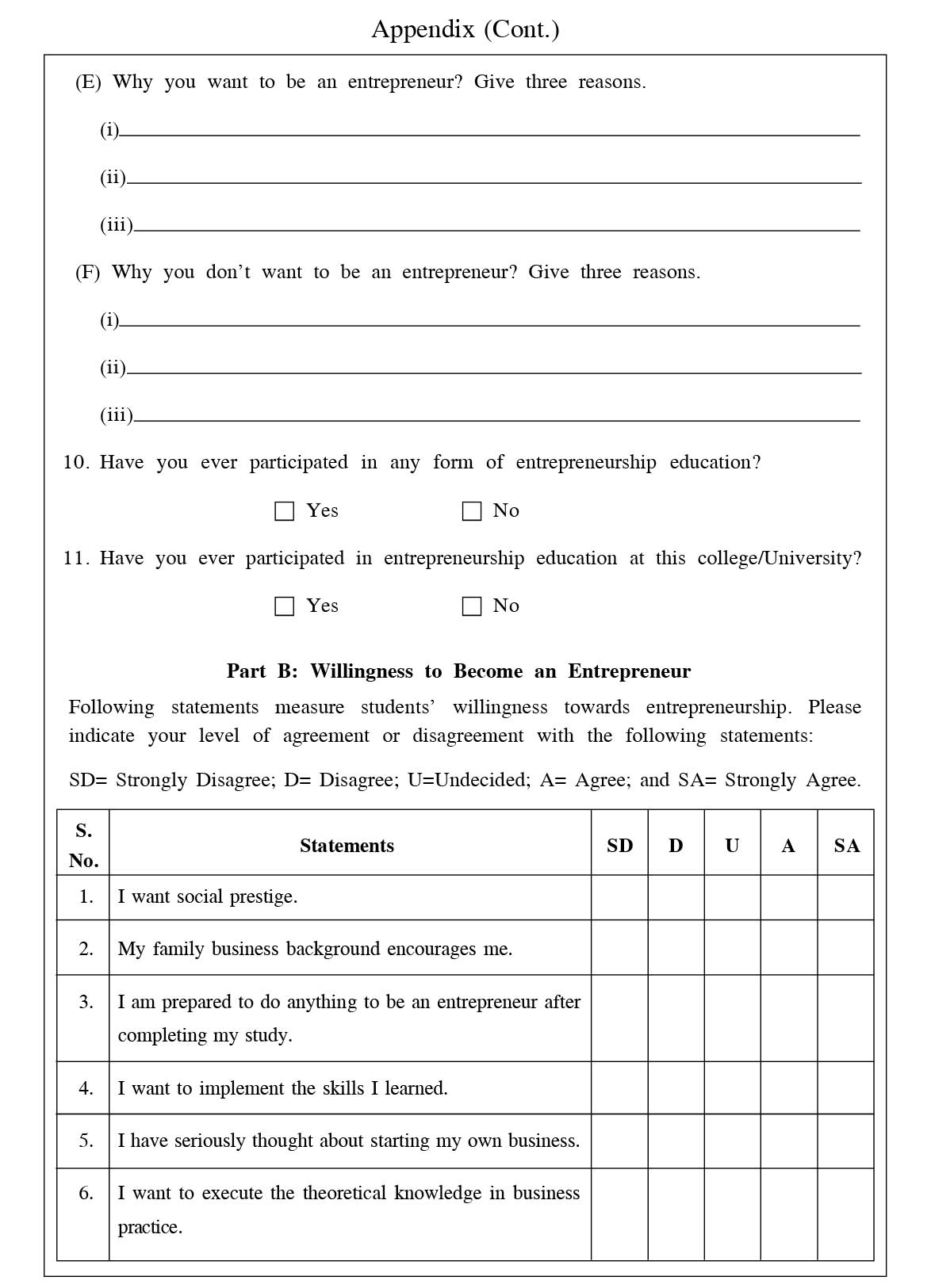

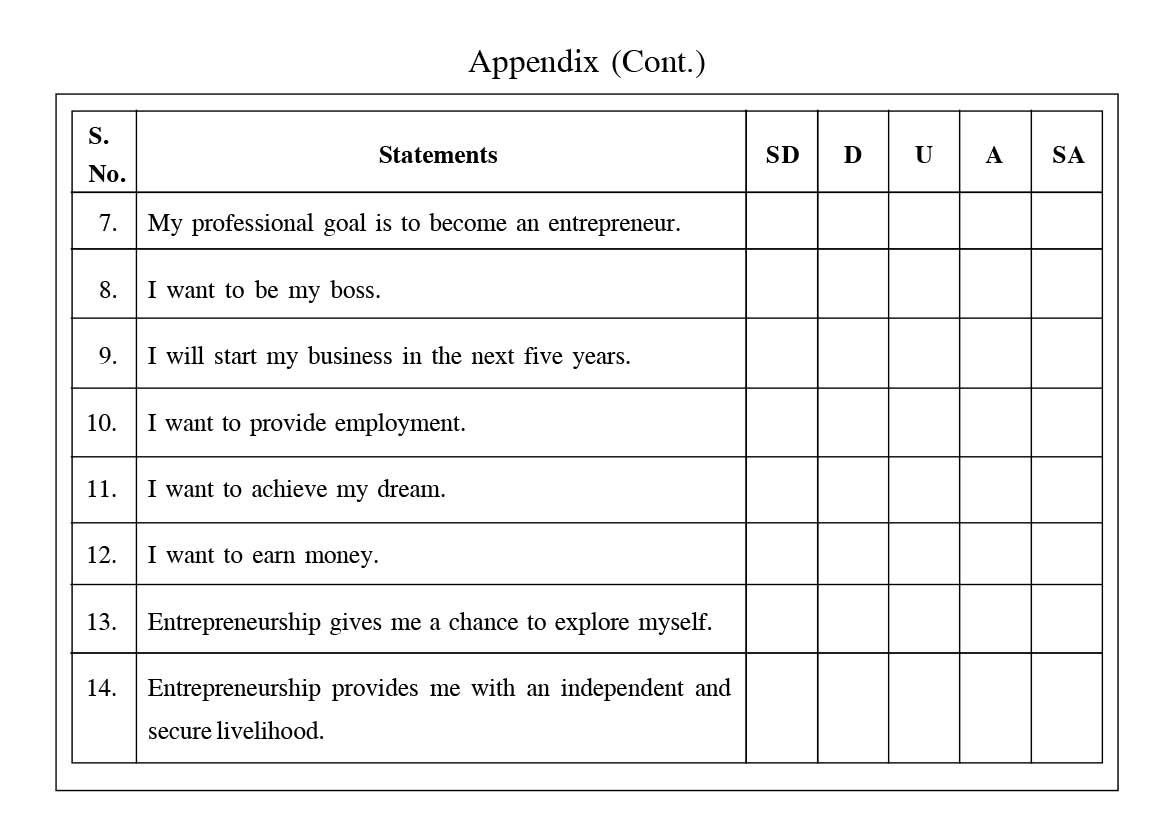

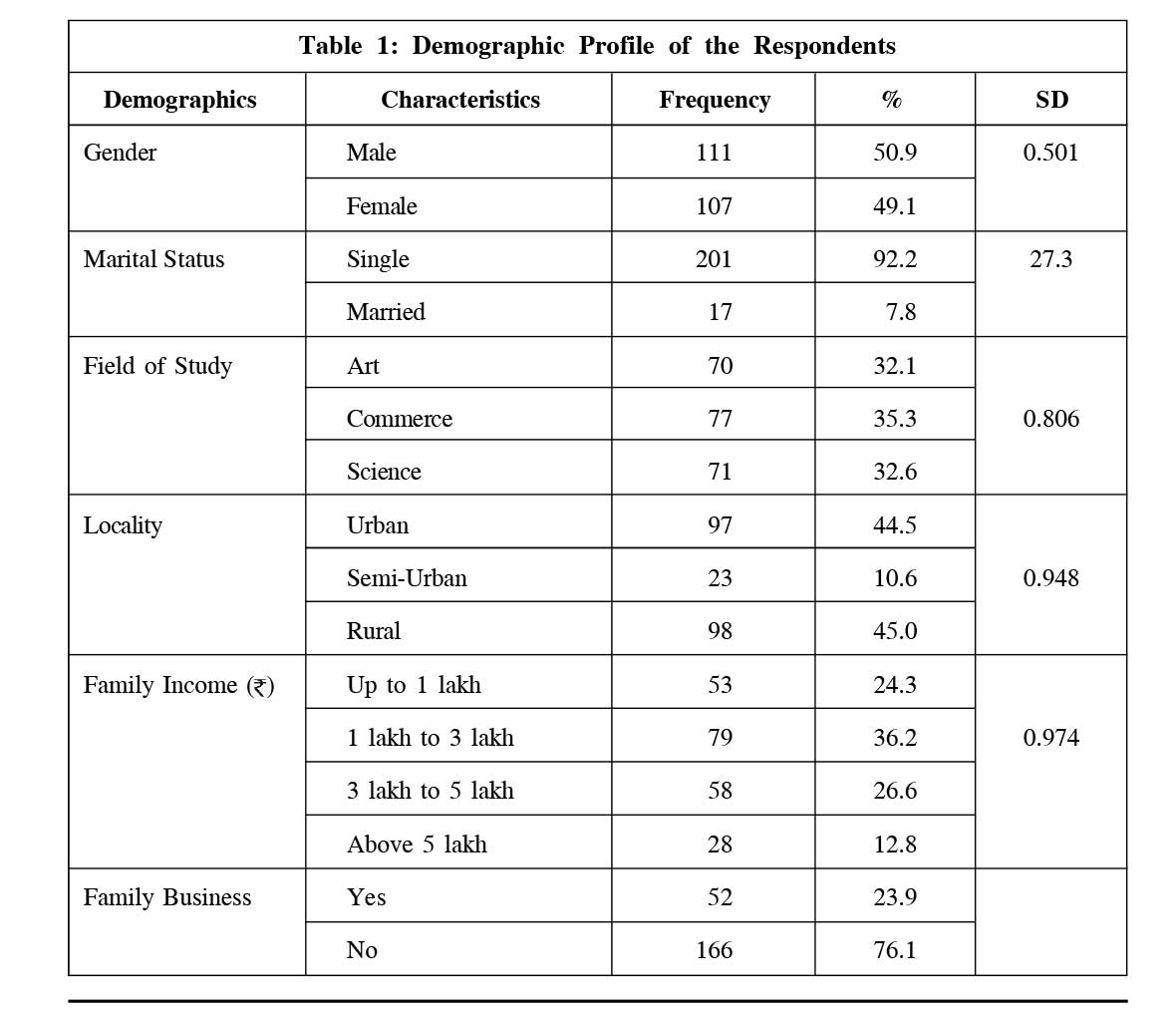

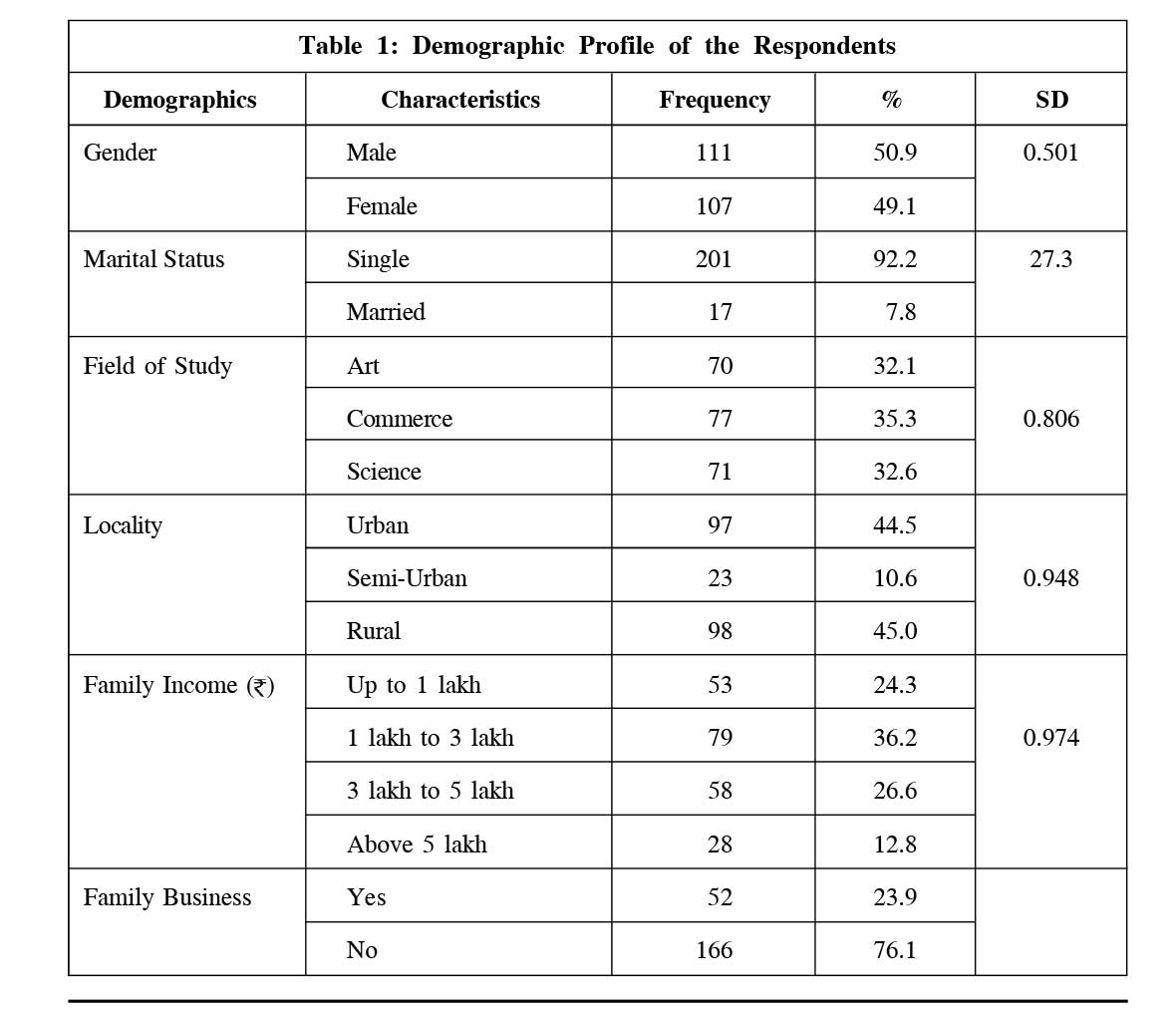

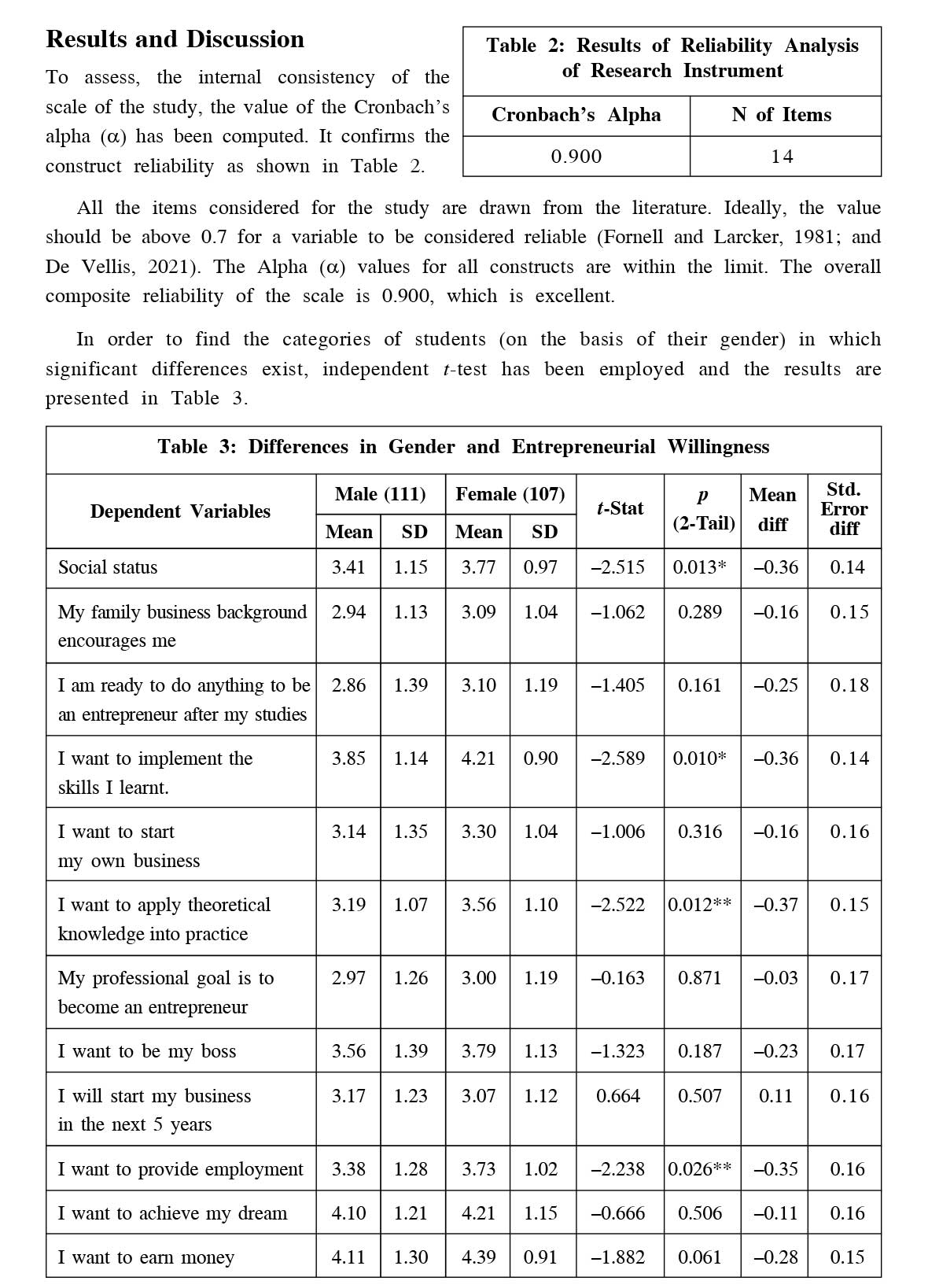

Table 1 presents the demographic profile of the respondents of the study. Out of the 218 respondents, 44.5% belong to urban areas, 10.6% are from semi-urban areas, and 45% belong to the rural areas. The questionnaire (see Appendix) has been developed through qualitative interview with university students, which was finalized with the help of the experts with necessary modifications at the later stage. For the purpose of collecting the data from the university students, we distributed a total number of 250 questionnaires among the respondents in December 2022. The final size of the sample includes 218 university students with a response rate of 87.2%. Out of the 218 respondents, 44.5% belong to urban areas, 10.6% are from semi-urban areas, and 45% belong to rural areas. Out of the total sample, 52 students have family business background and 166 students do not have any family business background. Out of the total respondents, 111 are males and 107 are females. To assess the difference in entrepreneurship orientation, students from three fields, i.e., arts, commerce, and science, have been considered.

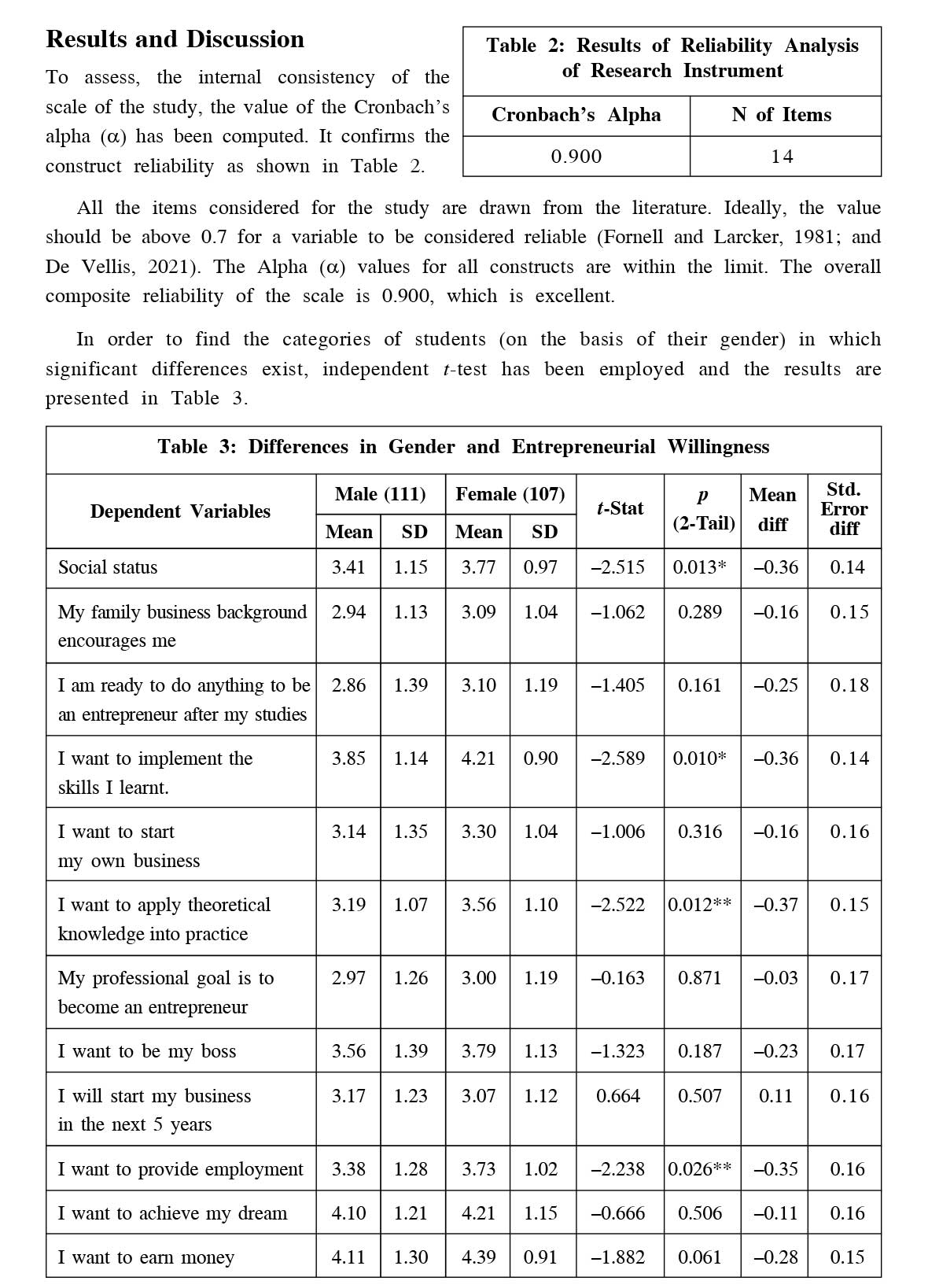

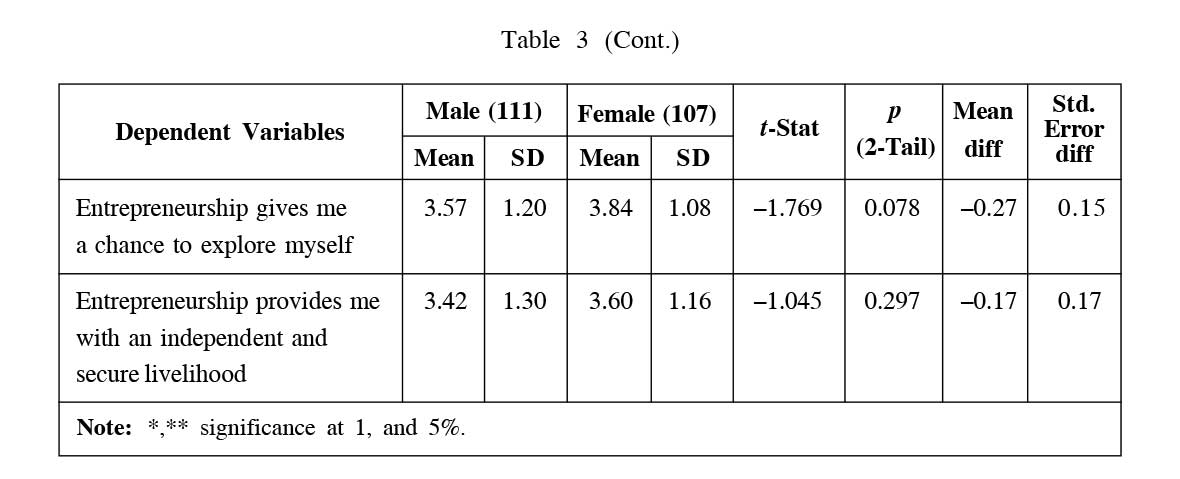

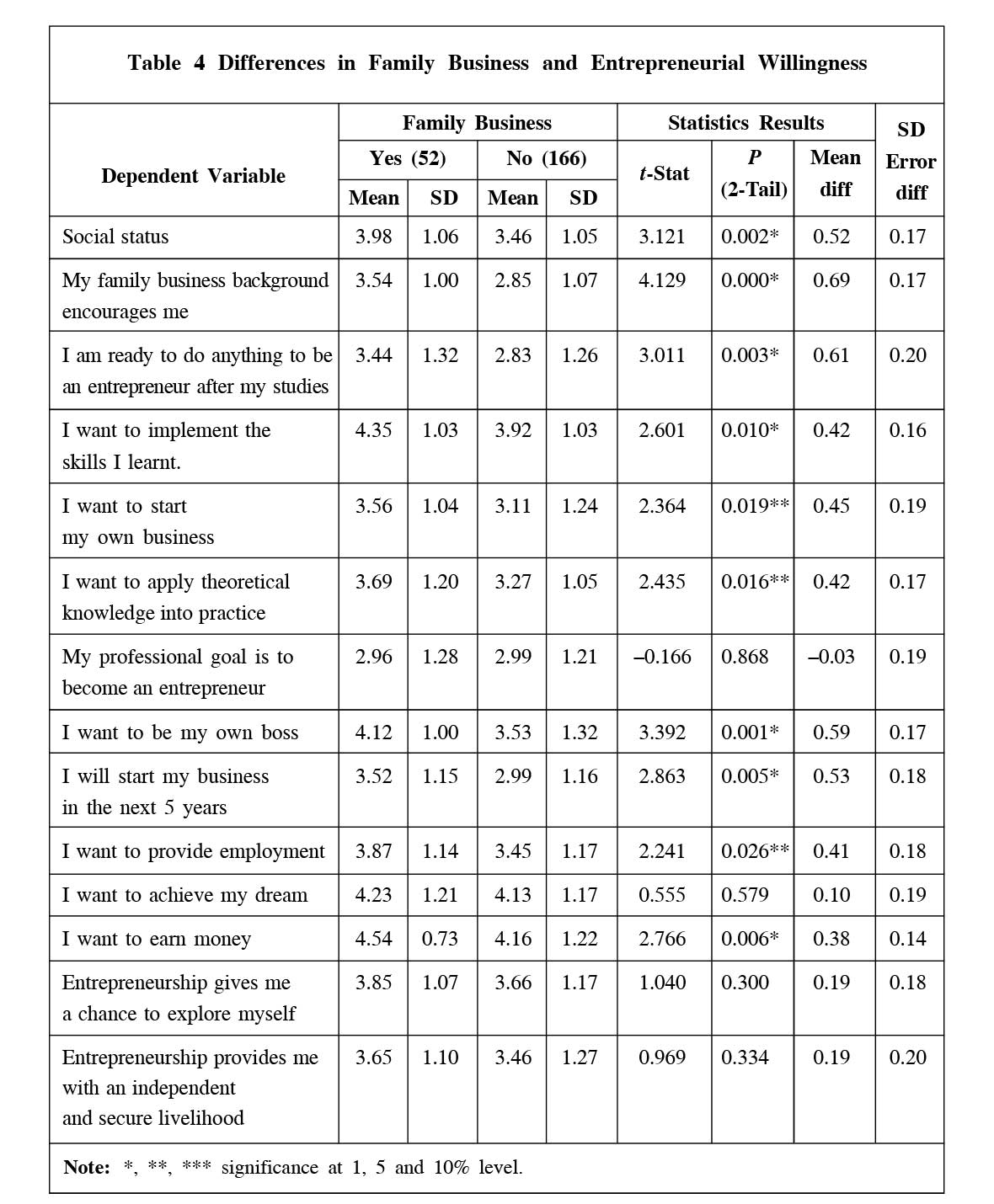

The results of the t-test confirm that there is a significant difference in willingness to become entrepreneurs among university students on the basis of their gender, social prestige, and implementation of their theoretical and learned skills in entrepreneurship (as p value > 0.05). The results show that female candidates want to be entrepreneurs because they want to implement their learned and theoretical skills in entrepreneurship and want to achieve social prestige in the society. Similarly, they are interested in generating employment through joining entrepreneurship (see Table 3 for more reference). They are willing to be job-givers in comparison to job-takers and wish to execute their learned theoretical knowledge in business practices as indicated by significant p-value for statements 6 and 10. Conversely, the hypothesis for statement 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13 and 14 is rejected as indicated by insignificant p-value in Table 3, which indicated that there is no significant difference in these variables for measuring entrepreneurship willingness among university students on the basis of their gender.

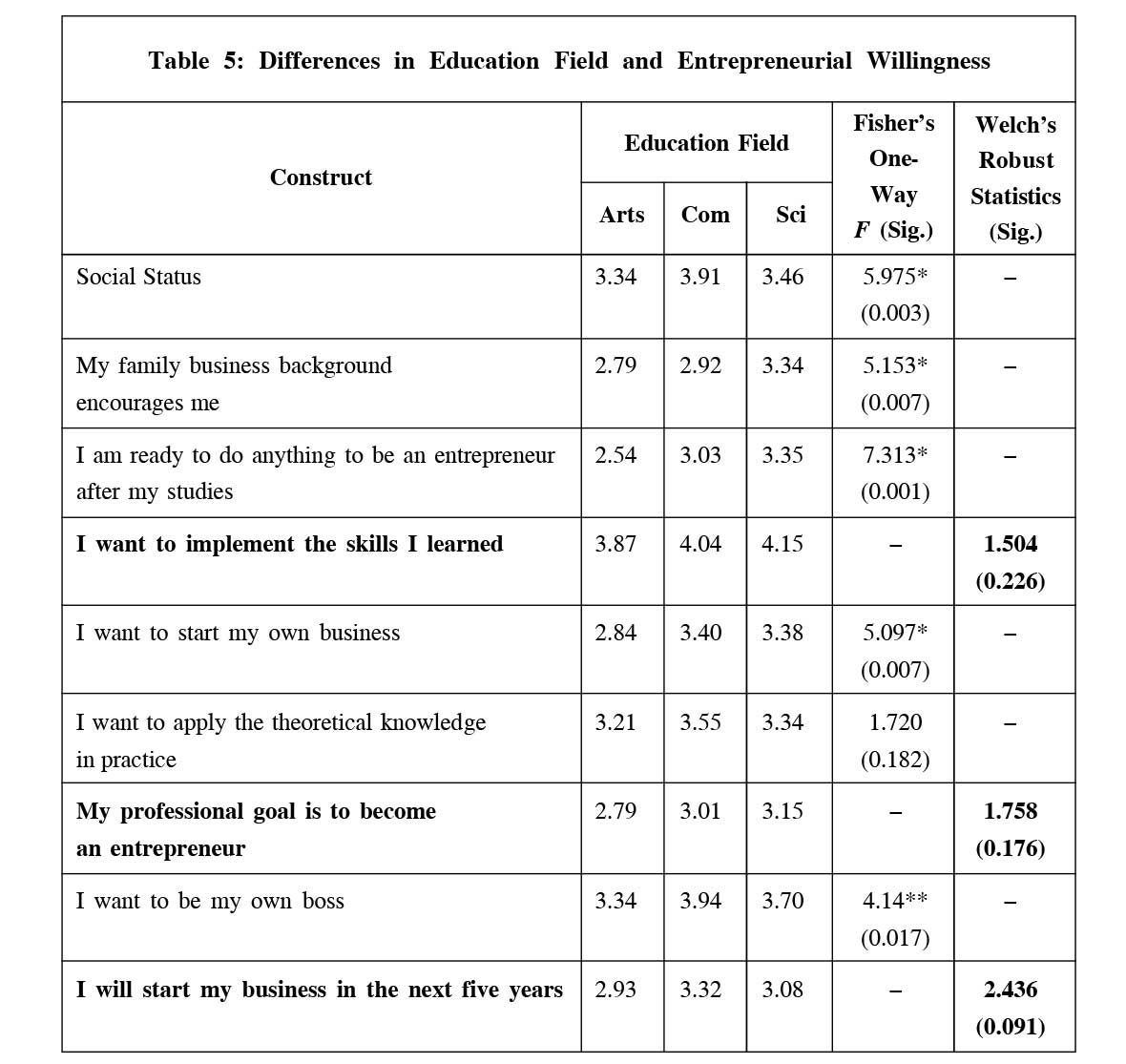

Similarly, results of the t-test on the basis of their family business (Table 4) confirm that there is a significant difference in willingness of university students to become entrepreneurs (as indicated by p value > 0.05). The impact of past family business on entrepreneurial willingness has been a topic of immense interest for researchers in the past few decades. Having a family business can increase the chances of an individual opting for entrepreneurship as a career choice because they gain exposure from family history and experiences of running a business (Kellermanns and Eddleston, 2006). The persons coming from family business are found to be more equipped to handle the challenges in entrepreneurship. It is not only about their ability, but the availability of resources also increases their willingness somehow, and as such, the path of entrepreneurship becomes easier for them in comparison to those without any exposure to a business environment. Family support at each stage is also a crucial aspect that can increase the willingness. However, it is also possible that having a family business background may have a negative impact on entrepreneurial willingness. Individuals may fear failure due to the pressure of continuing a family legacy or may feel pessimistic about their ability to control the outcomes of their entrepreneurial ventures (Wyrwich et al., 2016). Although entrepreneurial willingness depends upon a number of internal factors, coming from a family business background can

still have an impact on entrepreneurial willingness. Similarly, the results of our study show that having a family that is already engaged in a family business has a positive impact on students' willingness towards entrepreneurship, as indicated by significant p-value except for statements 7, 11, 13 and 14. Moreover, the level of entrepreneurial willingness is higher in comparison to those who do not have any family business background.

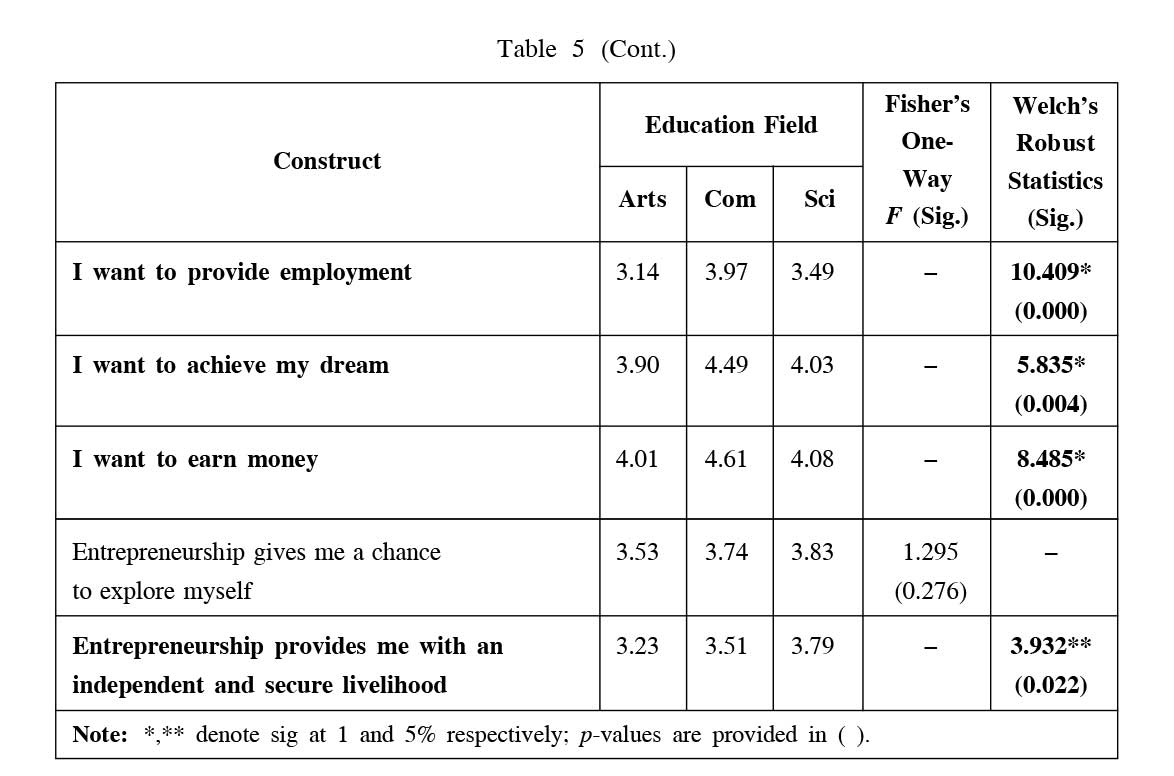

The study has applied the one-way ANOVA to check the differences in the entrepreneurial willingness of the university students based on their educational qualifications which revealed significant differences in social prestige, business acumen, and seriousness towards entrepreneurship of the students (Table 5). However, for statements 6 and 13, there was no significant difference in the entrepreneurship willingness of the university students, as indicated by insignificant p-values in the one-way Anova test. Similarly, for the data, with no homogeneity of variance, the Welch test was conducted that showed significant differences in entrepreneurial willingness of the students (one's own boss, employment generation, fulfilment of dreams and earning money) based on their educational qualifications (Table 5). On the contrary, there was no significant difference in the entrepreneurial willingness of the university students for statements 4, 7 and 9 as explicated by insignificant p-value. The results illustrate that commerce students have more entrepreneurial willingness in comparison to arts and science students.

Conclusion

The primary aim of the study is to measure entrepreneurial willingness among university students and the effect of demographic and socioeconomic factors on the same. The findings of the study indicate that females are willing to take up entrepreneurship compared to males. The stakeholders, while designing entrepreneurial education programs, should keep this in mind. Further, the results show that students with family business background and commerce as the subject have more entrepreneurial willingness. This reveals that those who are imparted entrepreneurial education have a competitive advantage. Moreover, being part of a business family also contributes to developing an entrepreneurial mindset.

References

- Aldrich H E and Cliff J E (2003), "The Pervasive Effects of Family on Entrepreneurship: Toward a Family Embeddedness Perspective", Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 18, No. 5, pp. 573-596. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(03)00011-9.

- Auken V H, Fry F L and Stephens P (2006), "The Influence of Role Models on Entrepreneurial Intentions", Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, Vol. 11, No. 2, pp. 157-167.

- Bandura A and Walters R H (1977), Social Learning Theory, Vol. 1, Englewood Cliffs, Prentice Hall.

- Binks M, Starkey K and Mahon C L (2006), "Entrepreneurship Education and the Business School", Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, Vol. 18, No. 1, pp. 1-18.

- Bosma N, Hessels J, Schutjens V et al. (2012), "Entrepreneurship and Role Models", Journal of Economic Psychology, Vol. 33, No. 2, pp. 410-424.

- Casson M (2003), "Entrepreneurship, Business Culture and the Theory of the Firm", in Handbook of Entrepreneurship Research, pp. 223-246, Springer, Boston, MA.

- Chakraborty S and Singh S K (2019), "Importance of Entrepreneurship Education Partnering for Employability of Fresh Graduates of Indian Universities", International Journal of Recent Technology and Engineering, Vol. 8, No. 1C2, pp. 126-130.

- Dabic M, Daim T, Bayraktaroglu E et al. (2012), "Exploring Gender Differences in Attitudes of University Students Towards Entrepreneurship: An International Survey", International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, Vol. 4, No. 3, pp. 316-336.

- Elliott C, Mavriplis C and Anis H (2020), "An Entrepreneurship Education and Peer Mentoring Program for Women in STEM: Mentors' Experiences and Perceptions of Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and Intent", International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, Vol. 16, pp. 43-67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-019-00624-2.

- Fernando J (2022), "4 Factors of Production Explained with Examples", Investopedia. Retrieved on September 6, 2022, from https://www.investopedia.com/terms/f/factors-production.asp

- Georgescu M A and Herman E (2020), "The Impact of the Family Background on Students' Entrepreneurial Intentions: An Empirical Analysis", Sustainability, Vol. 12, No. 11, p. 4775.

- Gundry L K, Ofstein L F and Kickul J R (2014), "Seeing Around Corners: How Creativity Skills in Entrepreneurship Education Influence Innovation in Business", The International Journal of Management Education, Vol. 12, No. 3, pp. 529-538.

- Hisrich R D, Shepherd D A and Peters M P (2017), Entrepreneurship, McGraw-Hill Education.

- Jonsdottir S J (2015), "Emancipatory Pedagogy: The Pedagogy of Innovation and Entrepreneurial Education", in 1st European Networking Conference on Entrepreneurship Education, p. 69.

- Karmarkar Yamini and Chhabra Meghna (2016), "Gender Gap in Entrepreneurship - A Taxonomic Review", Conference Paper on Quality Education, Entrepreneurship and Exemplary Business Practices for Social Change, Indore, Madhya Pradesh, India.

- Kellermanns F W and Eddleston K A (2006), "Corporate Entrepreneurship in Family Firms: A Family Perspective", Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Vol. 30 No. 6, pp. 809-830, SAGE Publications, Los Angeles, CA,

- Kim P H, Aldrich H E and Keister L A (2006), "Access (not) Denied: The Impact of Financial, Human, and Cultural Capital on Entrepreneurial Entry in the United States", Small Business Economics, Vol. 27, No. 1, pp. 5-22.

- Krueger N F and Carsrud A L (1993), "Entrepreneurial Intentions: Applying the Theory of Planned Behaviour", Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, Vol. 5, No. 4, pp. 315-330.

- Kumar S (2013), "Students' Willingness to Become an Entrepreneur: A Survey of Non-Business Students of President University", IOSR Journal of Business and Management, Vol. 15, No. 2, pp. 94-102. https://doi.org/10.9790/487x-15294102

- Lindner J (2018), "Entrepreneurship Education for a Sustainable Future", Discourse and Communication for Sustainable Education, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 115-127.

- Mani M (2015), "Entrepreneurship Education: A Students' Perspective", International Journal of E-Entrepreneurship and Innovation (IJEEI), Vol. 5, No. 1, pp. 1-14.

- Peterman N E and Kennedy J (2003), "Enterprise Education: Influencing Students' Perceptions of Entrepreneurship", Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Vol. 28, No. 2, pp. 129-144.

- Strobl A, Kronenberg C and Peters M (2012), "Entrepreneurial Attitudes and Intentions: Assessing Gender Specific Differences", International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, Vol. 15, No. 4, pp. 452-468.

- Turker D and Selcuk S S (2009), "Which Factors Affect Entrepreneurial Intention of University Students?", Journal of European Industrial Training, Vol. 33, No. 2, pp. 142-159.

- Ubong B (2017), "Entrepreneurship Education in Nigeria: Issues, Challenges, and Strategies", Nigerian Journal of Business Education, Vol. 4, No. 1, pp. 20-32.

- Van Praag, Mirjam C and Hans Van Ophem (1995), "Determinants of Willingness and Opportunity to Start as an Entrepreneur", Kyklos, Vol. 48, No. 4, p. 513-540. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6435.1995.tb01282.x.

- Wang C K and Wong P K (2004), "Entrepreneurial Interest of University Students in Singapore", Technovation, Vol. 24, No. 2, pp. 163-172.

- Wei X, Liu X and Sha J (2019), "How Does the Entrepreneurship Education Influence the Students' Innovation? Testing on the Multiple Mediation Model", Frontiers in Psychology, Vol. 10, p. 1557.

- Wu S and Wu L (2008), "The Impact of Higher Education on Entrepreneurial Intentions of University Students in China", Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, Vol. 15 No. 4, pp. 752-774.

- Wyrwich, M., Stuetzer, M. and Sternberg, R. (2016), "Entrepreneurial Role Models, Fear of Failure, and Institutional Approval of Entrepreneurship: A Tale of Two Regions", Small Business Economics, Springer, Vol. 46, pp. 467-492.