June'20

The IUP Journal of Entrepreneurship Development

Archives

Expertise and Cognitive Development of Entrepreneurs

Lehlohonolo Dongo

MBA Student, WITS Business School, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa.

E-mail: hlonie2@me.com

Brian Barnard

Researcher, WITS Business School, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa; and is the corresponding author. E-mail: barnard.b@polka.co.za

The purpose of this study is to evaluate the cognitive development and expertise of entrepreneurs and the impact thereof on the success of entrepreneurship. The existing theory on success factors for entrepreneurs is lacking in relation to the cognitive development and expertise of entrepreneurs. A qualitative research in the form of semi-structured interviews with experienced entrepreneurs was conducted. Data analysis and interpretation were undertaken using thematic analysis. The findings revealed that experienced entrepreneurs are characterized by enhanced quality of thinking and depth of processing information. This gives them the capability to schematically map interconnections by identifying problems and designing solutions for complex opportunities. In addition, it appears that experience is compulsory for novices to develop into experts. Consequently, a prolonged duration of exposure is required for novices to develop expertise. An evaluation of faster and effective methods of transferring entrepreneurship experience is necessary to expedite expertise.

Introduction

Cognitive development entails the level of thinking, depth of processing, cognitive complexity and cognitive efficiency through knowledge structures and cognitive scripts (Craik, 2002; Baron, 2006; Benet-Martinez et al., 2006; Krueger, 2007a; and Kalyuga, 2009). Expertise refers to practical competency (Collins and Evans, 2008), while it confers a leadership status to individuals in a particular domain of practice through intricate knowledge and skills (Chi et al., 1981). The constructs of cognitive development and expertise are not unrelated. In fact, the levels of cognitive development naturally correlate with the levels of expertise. Entrepreneurs, like any other professionals, ought to undergo significant training and development, gain experience and develop both in terms of cognition and expertise. The theory on the success factors of entrepreneurs and entrepreneurship has generally paid insufficient attention to the cognitive development and expertise of the entrepreneur. Similarly, policies regarding entrepreneurship primarily place emphasis on nascent entrepreneurs and disregard experienced entrepreneurs. A pressing question is whether experienced entrepreneurs are fully developed and whether there is a likely impact and effect on further development and support of experienced entrepreneurs. Little is known about the level of expertise of entrepreneurs and how this compares internationally. National expertise ceilings may help to explain entrepreneurship behavior and performance.

The purpose of this study is to examine the cognitive development and expertise of entrepreneurs and the impact thereof on the success of entrepreneurship. The study addresses the following research questions:

- How does the cognition of the entrepreneur develop, and how does it impact his or her success?

- How does the expertise of the entrepreneur develop, and how does it impact his or her success?

The study seeks to contribute to entrepreneurship and entrepreneurship development literature as well as entrepreneurship policy literature. Furthermore, it delineates the development of entrepreneurs and potential obstacles in this regard.

The study focuses on experienced entrepreneurs. The rationale for this selection is that experienced entrepreneurs would be well on their way in terms of their development journey. In addition, experienced entrepreneurs would be more advanced in terms of cognitive development and expertise. In studying the cognitive development and expertise of entrepreneurs, the perceptions of experienced entrepreneurs are primarily examined.

A key premise of the study is that experienced entrepreneurs may still have developmental needs and they may stall in terms of development. Consequently, they may benefit from unlocking further value through development. Furthermore, although there are no theoretical development ceilings, in practice entrepreneurs within a country may potentially hit such ceilings.

Literature Review

Cognitive Complexity

Benet-Martinez et al. (2006) explain cognitive complexity as content and structure; content as features and properties; structure as relationships and dynamics. Halford et al. (2007) explain that the human cognitive ability is largely determined by limitations of the working memory. The relationship between the working memory and reasoning is through the number of active items and interrelationships in the working memory and reasoning, respectively. Thus, reasoning and intelligence are directly affected by the level of the working memory. Both working memory and reasoning utilize a coordinate system to connect information that is relational (Halford et al., 2007).

Reasoning constructs thoughts by connecting elements to premises, while working memory captures the links between inputs. Thus, the coordinate systems in reasoning are described as relational. Subsequently, complexity relates to the number of relations of a certain cognitive function. In addition, several reconfigurations of the slots in different formations will give multiple dimensions or varieties of the relations that can be simplified through recoding which is called conceptual chunking (Halford et al., 2007). Since both the working memory and reasoning are constrained by the capacity of the coordinating system to accommodate elements, there is a limited amount of memory chunks and conceptual chunks that can be processed at a given time (Sweller et al., 2003).

Halford et al. (2007) note that expertise entails the ability to recode sets of multidimensional relations and segment complex tasks. Experts can deconstruct a multidimensional set of variables into fewer related dimensions through conceptual chunking. Similarly, complex tasks can be simplified through a systematic approach that divides the whole into constituent elements. The resultant of this approach is that the small constituents become amenable to being attended to individually in a segmented manner. Sweller et al. (2003) note the ability to formulate a hierarchical approach to tasks as what differentiates experts from novice learners. They suggest that the cumulative experience of experts builds the knowledge base that is essential for competency in domain-specific algorithms.

The ability to actively formulate algorithms to solve complex tasks is dependent on working memory. Furthermore, the passive application of algorithms to complex tasks as a consequence of repeated exposure bypasses the working memory. Experts efficiently use cognitive processes through their ability to link elements and relations with specific algorithms for problem solving. Novice learners on the other hand overstretch the working memory when confronted with complex situations, and are inefficient in their cognitive functions (Sweller et al., 2003).

Sweller et al. (2003) suggest that the use of schematic algorithms increased the versatility of the working memory. On the other hand, segmentation of variables mitigates for the working memory overload. This isolation of elements enhances the identification of interacting elements, as an initial step towards cognitive development. According to Bovair et al. (1990), the amount of content knowledge that is prerequisite to competency in a functional area relates to cognitive complexity. Similarly, goals, operators, methods, selection rules and production model had a positive association with the content and structure of the requisite knowledge for software operation, as illustrated by Bovair et al. (1990). Thus, cognitive complexity relates to the extent of the ease at which new skills can be acquired by novice learners.

Levels of Thinking and Depth of Processing

Craik (2002) illustrates that participants who were subjected to a stimulus that required both sensory analysis and identification of physical properties were immediately able to process the sensory input. The identification of the physical properties of the same stimulus was not immediately processed. Stimuli are perceptually processed according to strata ascending from early sensory analysis to later analysis of physical properties.

During the cognitive processing of physical features, the formulation of meaning is a delayed process as compared to the early processing of sensory stimuli (Craik, 2002). The extraction of meaning from physical properties is a function of a deeper analysis which entails multiple levels of sequential analysis. However, Craik (2002) postulates that early analysis and late analysis are not distinct isolated processes but a continuum that begins with analysis of sensory stimulus and proceeds to the analysis of conceptual properties.

The sequential multilayered analysis of an input has been identified as an essential feature in building memory capacity (Craik, 2002). Thus, the ability to retain and retrieve information is directly related to the complexity of the multilayered approach that is involved in the analysis of the input stimulus. It appears that the presence of more elaborate input pathways in processing a stimulus is linked to an enhanced storage and retrieval of the data. Craik identified the qualitative aspect of processing the input stimulus and the extent to which the processing of the input was carried out as the depth and elaboration, respectively. An input stimulus is converted into a unique memory unit based on a combination of the depth of processing, degree of processing and the contextual properties of the stimulus.

The process of retrieving information consists of matching the current stimulus to links in the coordinate systems rather than a mere recall from storage in a particular locus in the brain. The term short-term memory is a misnomer as it tends to refer to activation of a specific part in the brain. In contrast, the term primary memory refers to activity that is currently in progress (Craik, 2002). Thus, primary memory is inherent in the activation of the coordinate system such as when the mind is deliberately directed to focus on a particular object.

The absence of an objective tool to measure the depth of the layers in relation to the degree of memory achieved poses a weakness in the construct. An objective evaluation of the meaningfulness and elaboration of the permutation that has resulted from the in-depth analysis is essential to validate the role of the concept of depth in memory. The aspects of depth within the levels of processing include a thorough break down of meaning and extraction of relevant inferences (Craik, 2002).

According to van Hiele (1999), nonverbal thinking is an important, constant feature of routine daily activities and decision making. It was illustrated that nonverbal thinking is the precursor of the visual level of geometric thinking. The lowest level of thinking begins with the identification of the morphological features of objects. The descriptive attributes of objects are then further used to identify the observed objects through the descriptive level of thinking. The subsequent level of thinking advances to the application of logic to explain the object according to the specific attributes that are inherent to the object. This level of thinking is denoted as informal deduction which ought to be a prerequisite to formal education.

As per Applegate et al. (2002), there are specific attributes that should be exhibited to achieve high standards of reading. The ability to extract information from written text is a function of the reader's lived experiences combined with cultural background and language. The ability to extract meaning from text using lived experiences to explain, critique and make inferences forms the essence of a good reader. The impact of the content in the text should be viewed from the perspective of the change it created in the reader's state of mind rather than on the amount of the content that has been retained in the memory. Thus, good reader's ought to be defined by their ability to appreciate the practical applications of the content in the text.

Mitchell et al. (2007) are of the view that entrepreneurs are less inclined to systematic logic in their business approach, however, they are predisposed to adopting heuristic approaches to business. The advantage of this mindset is that entrepreneurs are more versatile and innovative in exploring opportunities. The traditional business logic that follows a scientific method is viewed as a hindrance to entrepreneurial creativity. It is argued that opportunities may be lost through analysis paralysis that may arise as a result of the traditional approach to business logic. The logic of effectuation is superior to systematic logic in entrepreneurship as it advances the ability to seize opportunities based on social networks, human and financial capital.

Reflection and Reinvention

Mann et al. (2009) define reflection as a process that involves undertaking a deliberate painstaking self-examination with regard to convictions or content of knowledge and implications thereof. However, the literature is replete with numerous definitions of reflection as observed by Mann et al. (2009). Reflection is an evaluation of thoughts through a process referred to as meta-cognition (Mitchell et al., 2007). Reflection adapts behavior to challenging practical situations (Korthagen and Vasalos, 2005).

Reflection could be viewed as a form of critical thinking that focuses on abstract complex matters with the intention to derive some form of resolution (Mann et al., 2009). Inherent to this endeavor is that the end point may lead to a reconciliation with the status quo without necessarily producing a definitive solution. Self-awareness and personal mastery form an integral part of reflection. Mann et al. (2009) argue that it is through reflection that individuals can have a better understanding of their emotional disposition and the impact it has on others. Reflection assists with reframing experiences to achieve personal development and change based on lived experiences.

Meta-cognition entails thinking, focusing on reflection, understanding and self-regulation to learn from experiences (Mitchell et al., 2007). It consists of self-awareness relating to memory capacity, self-assessment of understanding, and the inclination to act on the identified learning needs. Core reflection should emphasize strengths, not weaknesses (Korthagen and Vasalos, 2005). It is iterative and must build up. Since reflection is iterative, the goal thereof is to learn and gather skills or knowledge to be applied in future exposure or to modify behavior (Mann et al., 2009).

Cognitive Development

Cognitive research is categorized into four distinct divisions that investigate perception, decision making, use of knowledge and learning and cognitive development (Krueger, 2003).

An individual's level of attention, prejudice and awareness are examined under the category of perception. The ability to apply critical thinking skills and innovative problem-solving skills including the use of heuristics is sub-categorized under decision-making skills. While the efficient use of memory capacity and language skills represent knowledge disposition of the individual.

The cognitive construct is stratified into surface, deep structures and biological levels based on whether the depth of analysis is semantic, symbolic or neurological, respectively. The deeper analysis of knowledge occurs in a level that is embedded further down in the layers of thoughts (Krueger, 2003). Thus, activation of deep analysis involves the use of algorithms, interconnections and schematic representations which go beyond the triggers of surface structures. Intelligent people command superior cognitive performance through high-speed processing of representations, high memory capacity and a more complex schema of analysis (Chi et al., 1981).

The core of successful entrepreneurship is embedded in a mindset that commands expertise. Since expertise is a function of a shift in deep cognitive structures, experts are amenable to development through a learning process. Successful entrepreneurship can be achieved through a learning process that develops expertise. The inherent inclination of experts towards adopting sophisticated cognitive disposition and analysis process is congruent with the attributes described for intelligent individuals. The distinguishing feature of experts from novice learners is their ability to use deeper cognitive structures in processing knowledge representations (Krueger, 2007b).

Early Development

As adolescent cognitive development demonstrates, cognitive development entails a gradual transformation into expertise through maturing in reasoning and enhanced processing capabilities. It manifests as higher level thinking, in turn as abstract thinking, formulation of hypothesis, and multidimensional thinking, moral disposition, hypothetical thinking, increasing awareness and emotional astuteness, and development of real-life problem-solving skills. Cognitive systems have an essential role in the development of self-awareness and emotional disposition of individuals. The inputs and outputs in the cognitive system may have a direct trigger on emotional behavior and likewise cognition may dictate emotional expression (Steinberg, 2005).

Transitional States

Perry et al. (1988) note that a fragmentation of knowledge precedes successful knowledge integration and subsequent conceptual understanding in the future. Fragmented knowledge derives from wrong interconnections and thus, gaps in levels of understanding, which becomes evident. The gaps in the levels of understanding of a child can be elicited through observation of the common missing link on the same conceptual exercise. Children will tend to exhibit a predictable thinking process that is related to a particular concept based on their prevailing fragmented knowledge.

Perry et al. (1988) further note that transition to a more mature and comprehensive understanding occurs through the integration of existing conceptual blocks, and incorporation of any unintegrated knowledge. A child in the transitional state of knowledge will ultimately mature to a comprehensive understanding of concepts through integration of the existing conceptual building blocks. The understanding of the transitional state of knowledge forms the basis for the explanation of knowledge representation in the learning and behavior of children.

Learning and Cognitive Development

Problems can be viewed in a dichotomous approach depending on whether a problem is structured or unstructured (Krueger, 2007b). Structured problems tend to be well-defined and are amenable to a linear approach of problem solving. In contrast, unstructured problems are poorly defined and necessitate high levels of critical thinking and multidimensional views to resolve. In attending to unstructured problems, there is absence of preexisting knowledge and resources to tackle the problem. Furthermore, inherent to this set of problems is the possibility of existing interconnections and ensuing unintended consequences.

More continuous learning and development builds on deep cognitive structural changes, rather than the assimilation of knowledge. The inherent tendency to resist change may have a counterproductive effect on learning new knowledge and unlearning old knowledge. The principle of meta-cognition is at the crux of learning through awareness of the process of cognition and appreciation of the remedial interventions that are necessary to modify cognition (Krueger, 2007b).

Experts transition from being novice learners through the deep cognitive structures by mastering meta-cognition. The success of experts is embedded in the nature and development of their deep cognitive structures. Successful entrepreneurs are experts and by extrapolation they ought to possess the same cognitive capabilities as experts. This necessitates a change in the state of mind into one that is characterized by a deep understanding of one's thinking and an ability to self-regulate one's own learning. Human beings are amenable to transformation through life experiences which are referred to as developmental experiences. It is through certain experiences that some individuals modify their perception of the world thereby restructuring their existing knowledge (Krueger, 2007b).

According to social learning theory, learning forms the basis for a state of mind in which convictions and attitudes are constantly challenged to formulate knowledge through deep cognitive changes. The essence of knowledge is in the structure of knowledge representation as evidenced by algorithms and schematic understanding that is usually demonstrated by experts. It has been illustrated that experts exhibit the ability to continually grow their knowledge structure through the modification of their deep cognitive structures. An inquisitive mind has been identified as a critical requirement for problem-based learning approaches in the context of entrepreneurial creativity (Krueger, 2009).

There are parallels between entrepreneurs and digital game players where the role of internal motivation is characteristic of self-directed learning (Prensky, 2003). In these circumstances, successful execution of tasks is driven by the ability to rapidly assimilate and process the flow of information and commit to decisions instantly.

Pattern Recognition and Scripts

Patterns can be used to deconstruct complex systems to enhance understanding. The interconnections between patterns are uncovered with subsequent delineation of distant events and trends thereby enhancing the understanding of a myriad of phenomena. This is the essence of opportunity recognition that is characteristic of successful entrepreneurs since they tend to uncover hidden opportunities that are not overt to the novice learners. The development of prototypes and exemplar models is expected to expedite knowledge production in uncovering the interconnections that lead to the unique pattern recognition that distinguishes experts. Experts defer to their succinct representations of prototypes, schema and exemplars to identify uncovered business opportunities (Baron, 2006).

Exemplar models have been described as convenient tools that may be adopted by experts for decoding complex patterns as they mature from the developmental stages of learning through prototypes. Successful entrepreneurs rely on representations of patterns as directed by existing algorithms, schema, prototypes and exemplars to gain a competitive advantage in opportunity recognition. These representations are developed through cognitive structural changes over prolonged durations of meta-cognitive learning. Experienced entrepreneurs distinguish themselves with highly developed representations of pattern recognition and prototype constructs compared to novice learners (Baron, 2006).

In practice, novice learners build up their cognitive systems from a set of exemplars as points of reference for future decision making (Baron, 2006). According to Mitchell et al. (2000), the knowledge structure of experts derives from inquisitive interaction with practical and conceptual issues. Expert scripts entail packaging knowledge structures in long-term memory. The cognitive scripts act as recipe instructions for successful execution of defined tasks.

Emotional, Affective, Psychological and Other Aspects of Cognitive Development

Well-developed cognitive structures depend on continuous learning which will in turn reinforce and increase the number of representations in the knowledge structure (Krueger, 2007a). The practical implication of this assertion is that a desired goal can be achieved through a repeated exposure to the input stimuli such as entrepreneurial creativity or innovation. Cognitive behavior is prone to cultural and social contexts with a subsequent imbalance between cognition and emotional or social influence (Mitchell et al., 2000). Expert entrepreneurs exhibit emotional intelligence that is built on self-awareness, social networks and an audit of knowledge and skills (Sarasvathy, 2009).

Entrepreneurship and Cognitive Development

The combination of the ability to recognize opportunity, individual attitude towards risk and developed cognitive knowledge structures forms the core of the entrepreneurial mindset (Hisrich et al., 2007). Entrepreneurs are inclined towards heuristic approaches to business (Mitchell et al., 2007). The combination of cognitive knowledge structure as evidenced by well-developed algorithms and expert scripts is being at the core of entrepreneurial cognition (Krueger, 2009). The ability of entrepreneurs in identifying value creating opportunities is attributed to the combined cognitive frameworks that experts develop over time through exposure to learning opportunities (Baron, 2006).

Expertise

Expertise is defined as the command of intricate knowledge and skills which confers a leadership status on individuals in a particular domain of practice (Chi et al., 1981). The focus ought to be on practical competency rather than on the basis of a pure academic acumen (Collins and Evans, 2008).

Types of Expertise

A distinction is made between general expertise which is measured by the level of knowledge and specialist expertise which is domain-specific and competency-based. Practical competence is represented by contributory effort to the field of expertise through active participation which leads to sustainable development within the field of expertise (Collins and Evans, 2008).

Expertise can be viewed from the perspective of individuals who occupy the position of evaluating the competency of experts in a particular domain. This is regarded as external expertise since the individuals tasked with the evaluation are not experts in the domain. External experts include a category of individuals such as analysts whose cumulative knowledge about a specific domain over time equips them with sufficient knowledge to assess the experts within the domain. Internal expertise is defined as competency in knowledge relating to local people, events or products (Collins and Evans, 2008).

General expertise is either built from popular understanding, beer-mat knowledge or primary source. Common knowledge forms the basis of popular knowledge as information is disseminated and readily available to all individuals. The deliberate extraction of more knowledge regarding a specific subject from literature informs the acquisition of primary knowledge. The lack of domain specificity and poor knowledge immersion are seen as the distinguishing factors that delineate general expertise from specialist expertise (Collins and Evans, 2008).

The role of competency in the language of an area of expertise is defined as interactional expertise. This entails the proper use and adherence to guidelines and principles in the language of a specialist domain. The controversy about this type of expertise is that it seeks to suggest that competency in domain-specific language is separable from practical skills that are specific to the domain (Collins and Evans, 2008).

Mastery of language may be sufficient to understand a domain (Collins and Evans, 2015). Exposure to experts within a particular domain through multiple conversations is adequate to achieve competency in the language of the domain. Experts are endorsed informally through the relevant expert social networks they form part of. The resultant effect of socialization within expert groups is the passive acquisition of domain specific cultural and behavioral dispositions that are essential for expertise (Collins and Evans, 2008).

Knowledge Structures and Cognitive Development

Experts exhibit higher order chunks that have been developed through larger representations of patterns that are formulated in the knowledge structures (Chi et al., 1981). The highly developed and large knowledge structures of experts emanate from cognitive changes that are acquired through learning and experience (Collins and Evans, 2008).

Experts have in their possession a multitude of schemata, algorithms and patterns in combination with cognitive scripts that they refer to in order to navigate challenging situations. Skilled intuition is developed through recognition of patterns which is attributed to cognitive creativity. Experts rely on a plethora of patterns they have developed within their knowledge structures to effortlessly formulate relations that inform their intuition (Kahneman and Klein, 2009).

Expertise Development and Stages of Expertise

The role of experiential learning is noted as a prerequisite to developing knowledge structures that define experts. The transition from a novice learner to an expert is achieved through the gradual and initial acquisition of unstructured skills. Unstructured skills are distinctively human skills since they are not amenable to computation. This feature renders unstructured skills more labor-intensive to acquire since they are dependent on real-life experience to master. Thus, the cumulative total of an individual's exposure to a specific situation will ultimately build the expertise required in that domain (Benner et al., 2009).

According to Collins and Evans (2008), contributory expertise follows a systematic transition starting from the level of the novice learner, advanced beginner, competence and proficiency with the ultimate attainment of the expertise level. The novice learner is characterized by a complete lack of contextual understanding but adherence to explicit rules while the expert effortlessly and subconsciously considers the context without much consideration to rules. The stages in the middle exhibit a gradual transition from a rules-based approach to problem solving towards a holistic approach that takes into consideration the prevailing circumstances.

Exposure

Representations of schema and algorithms are based on integrated cognitive knowledge structure that takes into consideration multidimensional and abstract views. Benet-Martinez et al. (2006) observe complex cognitive representations that are characteristic of exposure to a different culture. Bicultural individuals are more likely to develop complex representations of their own culture and those of the host ethnic group through exposure to cultural frame switching experiences.

Transfer

The factors that may be at play in the transfer of knowledge consist of concealed knowledge, mismatched silence, ostensive knowledge, unrecognized knowledge and uncognized or uncognizable knowledge. These arise due to inherent hurdles that are associated with the transfer of knowledge such as the type and amount of knowledge that can be distributed in the case of concealed knowledge. Alternatively, there may be a lack of appreciation regarding the needs of the learner and vice versa; the learner may be unable to elicit the appropriate knowledge from the expert, resulting in a mismatch of silence (Collins and Evans, 2008).

In certain circumstances, there is no replacement for experiential learning thus ostensive knowledge becomes indispensable. In addition, there is passive learning that takes place during the process of learning through observation and this forms the basis for unrecognized learning. The notion of hands-on learning forms the basis of knowledge transfer in certain industries and this is the essence of cognized or uncognizable knowledge (Collins and Evans, 2008).

Expert-Novice Comparison

It is demonstrated that experts have mastered the identification of salient interconnections in patterns which renders them capable of reverting to a representative schema when attending to challenging situations (Ericsson, 2006). Ericsson (2006) draws a distinction between routine expertise which is based on repetitive tasks and adaptive expertise which is concerned with the performance of novel tasks associated with uncertainty and unpredictable outcomes. Experts are characterized by competency in comprehension of complex tasks, abstract concepts, hypothesis formulation, knowledge representation and meta-cognitive knowledge (Ericsson, 2006). Consequently, experts are inclined to apply a holistic approach to problem solving through enhanced communication and collaborative efforts by leveraging resources and their networks.

Since experts have a well-structured approach to problem solving, they tend to be successful in narrowing down the search compared to novices who keep a wide range of possibilities (Chi et al., 1981). Furthermore, experts tend to adopt a working-forward strategy compared to a working-backward strategy which is characteristic of novice learners. It is postulated that this is largely due to the fact that experts have a wide range of schema that is readily available in their armamentarium to enhance their efficiency.

The schemata that are designed within the knowledge structure of experts exhibit procedural knowledge. This enables experts to cover a wide range of issues that are involved in an issue holistically compared to the unintegrated knowledge of novices. The integrated knowledge of expertise allows them to be able to make appropriate inferences that are necessary to problem solving (Chi et al., 1981). Thus, the deficiencies in knowledge amongst novices are the cause for limitations in their problem-solving abilities.

Motivation

Creative individuals tend to exhibit a remarkable amount of self-motivation. A commitment to a particular area of interest is regarded as an indicator of resilience and success (Mumford et al., 2002). Creative people view their work and professional association as a continuation of their identity and they are often driven by the need to excel in their respective areas of expertise. This caliber of people is constantly looking for new learning opportunities and new skills as dictated by their own internal motivation.

Judging Expertise

Expertise is evaluated based on historical data of performance. The best method to evaluate experts is through expert review by colleagues in the same domain of specialty. The practice of peer-review also serves as a discriminating tool in the levels of expertise within a specific domain and across individuals who are non-experts and experts (Kahneman and Klein, 2009).

Among other things, cognition is developed through learning, experience and reflection. It entails depth of thinking and higher levels of cognitive complexity. Similarly, expertise is built up through practice. Greater cognitive development and expertise would lead the entrepreneur to see his environment and entrepreneurship-specific aspects, like opportunities, differently. There should be a marked difference in cognitive development and expertise between expert and novice entrepreneurs. At the same time, there is no reason to assume that cognition and expertise develop linearly, and a number of obstacles and hindrances, and also levels, may persist in this regard. Correspondingly, the purpose of the study is to further examine the cognitive development and expertise of entrepreneurs and the impact thereof on the success of entrepreneurship.

Data and Methodology

Research Paradigm

The two broad categories that are applied in research methodology are qualitative and quantitative research methods. Research inherently involves both qualitative and quantitative elements in varying degrees of dominance (Creswell and Creswell, 2017). The predominant research method depends on the research question being asked. A mixed research method arises in the event that a research methodology is composed of representations from both qualitative and quantitative methods (Creswell and Creswell, 2017). A qualitative research approach offers the ability to extract in-depth understanding and analysis of behavioral patterns, cognitive thinking and subjective experiences of individuals (Hanson et al., 2005).

The role of qualitative research in eliciting behavioral patterns that are associated with particular outcomes is well-established (Creswell and Creswell, 2017). An analysis that focuses on individuals will unearth the golden thread and provide deep insights into the knowledge attributes associated with opportunities for successful entrepreneurs. A qualitative research in the form of semi-structured interviews was adopted in this study to elicit the maximum amount of information that is available to understand and interpret the cognitive mindsets of experienced entrepreneurs.

Research Design

Data collection was conducted through semi-structured interviews. This technique is identified as having wide applications in the context of qualitative research (Tong et al., 2007). The aim is to leverage the benefits of this technique such as the engaging interaction and the ability to interrogate deeper into the information given by the participants (Bell, 2014). This is expected to facilitate the extraction of the deep and meaningful understanding of the expertise and cognitive aspects that are associated with experienced entrepreneurs.

In addition to the inherent engaging nature and the setting that allows cross-questioning in semi-structured interviews, this technique is also conducive for flexibility and evolution depending on issues that arise during the interview. The caliber of participants for this exercise may not be easily accessible and there is a limitation to the sample. Furthermore, an evaluation of individual experiences is inherently associated with a risk of bias (Bell, 2014).

Population and Sample

A population consists of all the items or people that are concerned with the subject under investigation. In this study, the population entails all entrepreneurs in South Africa. Although an analysis that includes the entire population is ideal, this is not always practically possible and it may be froth with a myriad of analytical challenges (Kothari, 2004).

Sampling is approached using probability or non-probability sampling (Blaxter, 2010). Probability sampling entails randomization in which participants are subjected to a determined opportunity to be selected. A non-probability sampling is a deliberate bias towards participants that meet the criteria as dictated by the purpose and objectives of the study.

A selective non-probability sampling technique of target participants who met the criteria in accordance with the purpose and objectives of the study was applied. This is associated with optimal extraction of the depth and breadth of the required information since participants that meet the requisite knowledge possession and the ability to express such knowledge are selectively targeted (Beukel et al., 2014). Entrepreneurs that are either accomplished academically or in business for a minimum of three years, or with one successful business or partnership were considered.

There was no discrimination according to industry since expertise and cognitive development is not viewed as industry dependent. The total number of participants to be interviewed was capped at 10 to mitigate for the potential risk of saturation that may arise in excess of this number. Access to experienced entrepreneurs was achieved through professional social media platforms and professional networks. The identified respondents were then contacted telephonically or via e-mail.

Research Instrument

An interview framework in a qualitative research achieves the objectives of the research by aligning questions to the research question. The approach to the interview is the creation of an enquiry-based conversation with open-ended questions to optimize the extraction of depth (Castillo-Montoya, 2016). An interview schedule (see Appendix) that outlines the questions for the interview was used to direct the conduct of the interview. A semi-structured interview with each participant was carried out by following a set of open-ended questions listed under the specific categories of concepts that relate to the expertise and cognitive development of entrepreneurs and innovators. The estimated duration of each interview was approximately one hour.

Data Collection

A schedule of one-on-one appointments with all the selected participants was compiled. All efforts were made to conduct the interviews on the basis of convenience in respect to time and place for the participants. While notes were taken during the interviews, permission to conduct voice recordings of all interviews using a digital recorder was solicited in advance. The benefit of using a recorder as a complimentary tool to note taking during qualitative research is associated with preservation of the original raw data (Blaxter, 2010).

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Thematic analysis is defined as a tool that can be applied to delineate the presence of patterns and analyze these patterns to decipher the desired meaning from a qualitative research method. Although thematic analysis is ubiquitous to most of the analytic techniques, there is barely any consensus regarding its definition and role in the literature (Braun and Clarke, 2006). In this study, thematic analysis was applied to establish the patterns, stories and themes displayed by expert entrepreneurs. Thematic analysis in the context of a constructivist paradigm is not influenced by individual psychological disposition but is based on socio, cultural and structural aspects that account for specific outcomes (Braun and Clarke, 2006).

Thematic analysis was then used to translate the patterns, narratives and themes into a meaningful and rich understanding of the factors involved in acquiring the requisite expertise and cognitive development that is associated with entrepreneurs and innovators. Through its theoretical framework, thematic analysis preserves the innate representation of complex data while ensuring a detailed and meaningful explanation (Braun and Clarke, 2006). The datasets were analyzed for patterns, themes and narratives that signify meaning and reported accordingly. This was conducted in the form of reading and listening to the audio recordings while taking notes and highlighting points of interest at the same time. This included the verbatim transcription of the audio recordings in a manner that preserved the contents of the original conversation during the actual interview.

The process of encoding was resumed once the datasets had been categorized and points of interest identified. The patterns or themes of interest from individual extracts of data were then manually ascribed to codes that identify specific features in the datasets. Following the coding and collation of themes or patterns, the codes were grouped according to themes or patterns. This included further sub-categorization of themes into larger encompassing themes or patterns using tables. Subsequently, the themes and their associated sub-themes were defined according to meaning or context. The analysis of the themes was undertaken based on the narrative presented by each theme and the relevant available literature.

In summary, data analysis and interpretation was conducted using the following sequence as suggested by Braun and Clarke (2006):

- Familiarization: This entailed data collation and transcription including an analysis of depth and richness in the data and the presence of recurrent themes and ideas.

- Coding: Generation of initial codes that were ascribed to specific concepts for the development of a thematic arrangement.

- Review of Themes: Arrangement according to the categories and subcategories that defined the data. This included the identification of datasets that are not allocated to any category.

- Charting: The data was allocated to the respective themes, categories and subcategories using tables.

- Mapping and Interpretation: The themes were defined and interpreted according to main categories and subcategories.

Validity and Reliability

Validity

Validity in qualitative methods is defined as the extent to which the research depicts an accurate representation of the subject under investigation (Creswell and Miller, 2000). Internal validity is a measure of consistency between the findings and the actual environment while external validity is concerned with the generalizability of the findings (Morrow, 2005). External validity in this study was rendered unnecessary due to the sampling method which is in favor of a rich and deep understanding of the datasets. Validity in the qualitative research can be viewed as the equivalent of statistical analysis in quantitative research (Morse et al., 2002).

Validity is a central concept in ensuring that there is confidence in the conduct of research methodology through the use of rigor as a control measure (Morse et al., 2002). The method used to ascribe rigor or trustworthiness to qualitative research is largely paradigm-specific (Morrow, 2005). A distinction is made between common assessment tools of rigor such as the amount of immersion into the data, amount of data and interpretation and paradigm-specific measures of rigor (Morrow, 2005). Internal validity was ascertained through a pilot study to confirm consistency between the objectives of the study and the actual milieu. Internal validity was further improved by careful selection of participants to be interviewed.

Reliability

Reliability is defined as the extent to which a research methodology is reproducible without major discrepancies between different investigators using the same techniques and under a similar context (Morrow, 2005). Through the research instrument and framing of unambiguous questions with the aim of eliciting the same understanding from the perspective of the participants and the investigators, reliability was optimized. The fact that semi-structured interviews were used also helped. There was some flow or consistency across interviews.

Results

Cognition Development of the Entrepreneurs

The Contrast Between Expert and Novice Entrepreneurs

It was noted that expert entrepreneurs acquire experience from previous learning and practical exposure. The expert entrepreneur has had the benefit of repeated exposure to the same challenges, this renders them successful in approaching problems with confidence. In contrast, the novice has not gained the experience to build the necessary confidence in cognitive abilities. Consequently, novices may become overwhelmed when presented with a problem while experts will approach the problem with more confidence. One respondent noted that experts tend to be certain about things which may have a negative impact on knowledge as the willingness to learn diminishes. Novice entrepreneurs tend to rush into an idea and stumble without thorough evaluation.

Expert entrepreneurs use a combination of skills, background and hands on experience to run businesses. A distinction can be made between entrepreneurs with a spectrum of academic qualifications, including postgraduate studies and those that are just out of school. Higher levels of cognitive development are associated with previous experience and the ability to recover from failure. First time entrepreneurs were described as being unrealistic and naive. This usually manifests as the low level of maturity in their business plans. However, there are instances where experienced entrepreneurs may also appear to be struggling with business plans. Experienced entrepreneurs have an advantage because they are more developed and more refined in terms of decision making and problem solving.

Critical Experiences That Shape Development

Some of the crucial experiences include practical exposure in identifying existing need, and selling and finding creative solutions to problems. The lessons include learning to identify opportunities and gaps that can be seized in the market. Novice entrepreneurs are expected to develop their skills by gradually getting involved with complex projects to grow their experience. This will build past experiences that can be relied on to approach similarly challenging problems in the future. Entrepreneurs should develop a mindset that understands the value of collaboration in tackling complex projects through developing their skills in teamwork.

One of the most valuable experiences was getting direct exposure to persuade, pitch or sell to clients. This serves as a preparation on how to handle rejection and still not give up. The other lesson was on dealing with failure as an entrepreneur. The most spectacular failures were regarded as the most important lessons for future success. A background in business and formal education were found to be advantageous for success as an entrepreneur. In addition, early exposure to entrepreneurship and innovation yields even better results in developing problem solving skills and building confidence.

Novice entrepreneurs should start by seeking logical explanations and reasons for what works and what does not work. The aim is to gain knowledge and perspective through education while learning to apply the knowledge. This should then advance to continuous learning and new ways of thinking that are relevant. Exposure to failure and learning from it contributes a lot to development and acquisition of the skills that are necessary to thrive as an entrepreneur or innovator. Participation in activities such as public speaking and teaching others assist in developing communication skills, engaging with people, decision making and negotiation skills.

Experiences That Shape Development: Experiences that involve struggle, failure and running into walls were cited as being crucial for development. However, struggle must be accompanied by small wins that will shape the thinking of the entrepreneur. Success and failure should then be processed through reflection to enhance understanding and interpretation. There are also bigger lessons to be derived from success.

The ability to pitch and sell was regarded as the absolute minimum skill, while education and skills in areas such as finance are important. Emotional maturity and the ability to remain motivated were regarded as essential to enable novices in handling rejection and failure. A background in business is the minimum experience novices should acquire for success as entrepreneurs and innovators. Access to networks was noted as being critical for starting a business as it may expedite progress.

While ego may impede development, humility, learning to screen, refine and develop an idea were noted to be essential. In addition, the ability to develop a minimum viable product and a lean start-up approach were important for success. Entrepreneurs ought to be able to validate a concept, its assumptions and premises in the market before it is even completely developed. They should learn to run and manage a business and not only focus in one aspect such as the technical competency. They should develop their financial management skills and development of ideas including financing of ideas and testing ideas before implementation.

Entrepreneurs need to understand the regulatory framework that guides their industry of interest. An understanding of the value of good customers, bad customers and the value of money is essential. Failure is likely to expose novices to faster and more honest learning. An opportunity to execute on whatever idea one has, or innovation is necessary to experience either failure or rejection. Novice entrepreneurs have to progress from the ideation stage to implementation. Implementation is a crucial experience for the development of entrepreneurs and innovators.

The Adequacy of a Basic Cognitive Base

Initially, there is a lot of intuition that even novices have but there is a need for cognitive base and experience for growth. Intuition alone is not enough, it is imperative to read books, attend conferences and talk to experts to get other people's experiences to supplement knowledge gaps. Intuition ought to always be checked analytically to shape the thinking and interpretation. Intuition is key to the development of an entrepreneur and it is reinforced by previous experiences.

In case of minimal business experience of family business background, intuition becomes limited. Intuition must be supplemented with knowledge and specific skills to succeed as an entrepreneur. The basic cognitive base would be limited by the entrepreneur's academic expertise, business acumen, cultural and social capital. In addition to the entrepreneurial capital they will possess some basic business skills. An entrepreneur needs innovative skills, business skills, financial management skills and marketing skills to run a successful business.

Adequacy of Adopting the Role or Identity of an Innovator or Entrepreneur

A reliance on the willingness to adopt the role or identity of an entrepreneur as the motivation is and can actually be dangerous. In this approach, there is no assurance that there will be application of process, wisdom or skill. There is a risk that the entrepreneur may simply allocate time and energy into unrefined or poor ideas. While attitude is a small component of entrepreneurship, skill forms a large component of entrepreneurship.

Willingness and adopting a role of an entrepreneur is not sufficient for highly complex businesses. Regardless of what is meant by off the ground, willingness is required and is sufficient to get off the ground. The willingness to try is absolutely essential as a starting point. An entrepreneur has to believe that it can be done, and it is possible to succeed. However, this may not be sufficient to advance to subsequent levels of growth. Entrepreneurs need to have the flexibility to adapt to changes in the event that their idea does not work.

Contribution of Entrepreneurship Literature and Material

The tools learnt will not guarantee the achievement of the milestones by themselves. The tools cannot replace the practical understanding of the dynamics that are involved when dealing with people. It was emphasized that it would be very hard to become an entrepreneur from just reading books even if the knowledge is good. Experience involves interacting with people and getting involved in servicing people. Reading will support the development of knowledge on entrepreneurship and entrepreneurs, but it is not sufficient by itself.

Most books on entrepreneurship contain a minimum amount of knowledge or starting point for entrepreneurs. Some material on entrepreneurs and entrepreneurship is mostly motivational than educational and it is without guidance. Even with many years of experience in business and with customers, there are still a lot of surprises in terms of what the market, regulators and customers can do. Occasionally, if adopting the value of the identity of being an entrepreneur has an effect to the willingness to start then it may work.

An entrepreneur can gain experience and knowledge through exposure to other entrepreneurs. This can include reading case studies and biographies of role models. While this will take a novice a few steps further towards achieving their goals, this type of exposure on its own is not sufficient. In addition to acquiring knowledge, an entrepreneur also needs practical experience and must possess the flair for entrepreneurship.

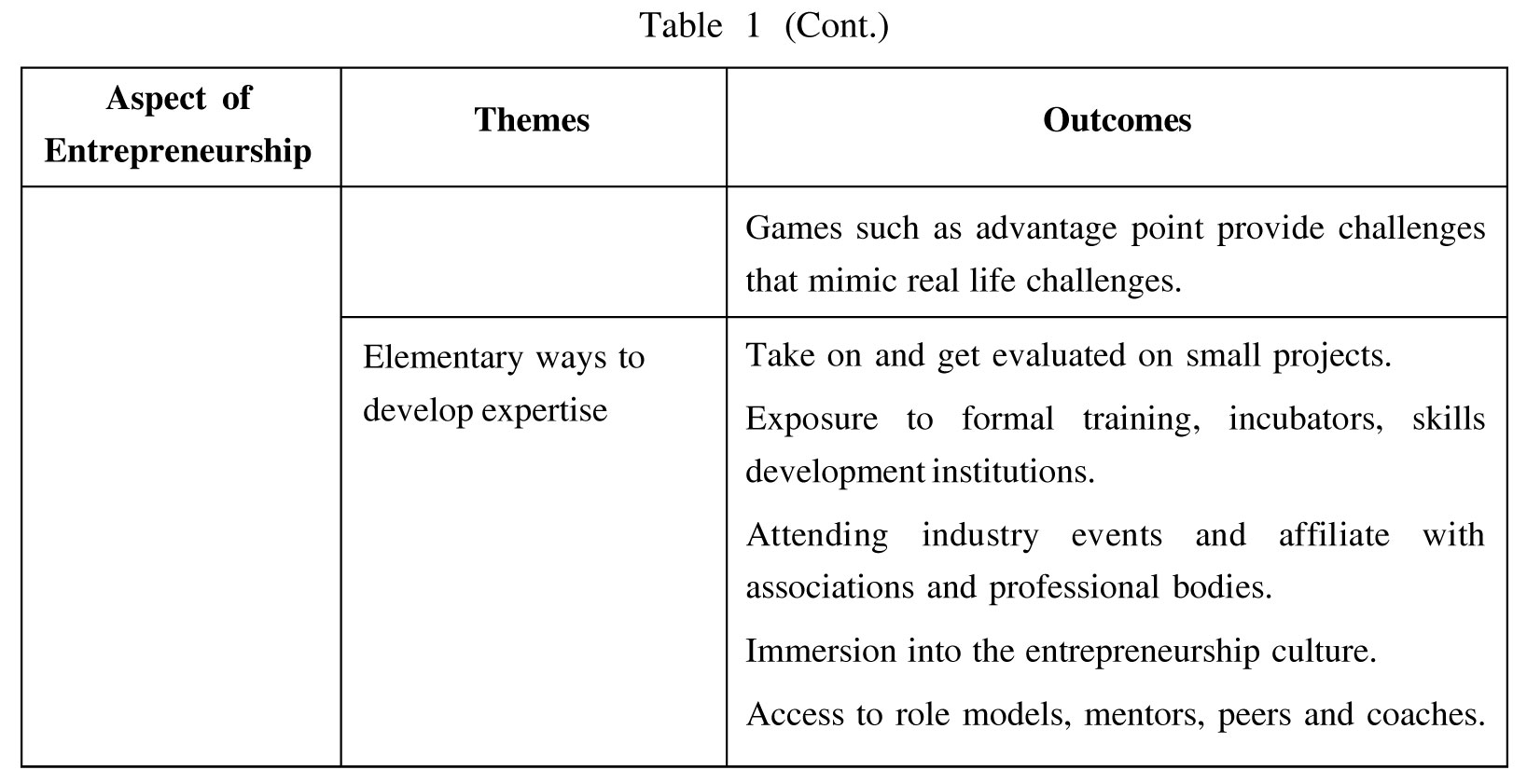

Elementary Ways to Develop Expertise

Some of the options include formal training, incubators and skills development institutions which provide training for free. These programs can give a lot of value for free. Attending industry events is one way that one can take advantage to develop entrepreneurship and innovation expertise. It is important to know the associations and professional bodies within the industry and spend time in those associations. Peer groups and mentor groups are also valuable and cheap sources of quick information.

Learning from other entrepreneurs as role models is one of the best ways to develop experience in innovation and entrepreneurship. For instance, children who are raised by entrepreneurial parents gain practical experience on how to serve customers and run businesses from a very early age. Schools can also provide an environment that encourages innovation and stimulates thinking to come up with new things. Learning entrepreneurship can actually involve one's own business. However, it was emphasized that every novice entrepreneur needs a mentor. There is no set outline for all entrepreneurs to follow when learning. Mentorship offers custom education for each individual entrepreneur.

Mentoring may be an effective, cheap way of educating entrepreneurs. The entrepreneur can acquire knowledge on entrepreneurship through books and online while their understanding and application of the material is monitored by someone with experience. Tools such as brainstorming and listening to customers are simple ways of learning. Innovation is a skill rather than a talent and it can be learnt through practical exposure. A lot of people read up and have awareness and are knowledgeable about what is happening but are not able to become part of what is happening.

One of the simplest and cheapest ways to develop entrepreneurial skills is to start with games such as advantage point. This game will expose novices to all the challenges, opportunities, stresses and anxieties of entrepreneurship without any real financial risk. A more effective way would be to experience a life changing experience such as becoming bankrupt. Successful entrepreneurs have the ability to recover from the most difficult situations. Novices can also use online resources for research and engage with experienced entrepreneurs.

Stepping Stones as Learning Stages

The first step is to understand one's own real skills and weaknesses, so as to leverage on strengths and mitigate for weaknesses. Entrepreneurs should have a solid idea of the product or value they are bringing to the market. Values should reflect even in the entrepreneurs' personal life. Secondly, novices can engage other entrepreneurs who are at the same level as themselves or above. Even reading about successful entrepreneurs will be a good start. It is advisable to start with a small project in terms of development and break it up into pieces. The business is then turned around to build on that. The process of entrepreneurship development can be messy, and the steps can be mixed up.

Some of the most important stepping stones are an understanding of one's own passion and an understanding of the industry and passion for the industry that one is interested in. It is important to collaborate or come together with other entrepreneurs during the idea generation stage. The entrepreneur should consider sharing ideas with others, this will help develop ideas. The benefits may be greater than the risks and most ideas will still need further development.

It is more valuable to receive feedback from other entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurs must learn to screen ideas and do market research as the initial step. Other basic everyday tools for entrepreneurs to learn include improving and streamlining idea development, prototyping, market research and evaluation and idea prioritization.

Novices can start with small challenges such as selling simple products. They should go through some hurdles and be exposed to failures but also experience some successes. They can be given a chance to conduct market surveys to develop the skills needed to approach clients and explain their product. A gradual introduction to selling their own products can then follow. This will introduce them to learn rejection, even if they give away something for free.

One of the cheapest ways is to work with other innovators and entrepreneurs and try to solve their problems. The core of innovation and entrepreneurship is problem solving whether for convenience or any other reason. Entrepreneurs can learn from these exercises and equip themselves with skills and develop their thinking in a way that can be used to solve their own problems. There are many problems that can be solved without necessarily requiring money or even making money.

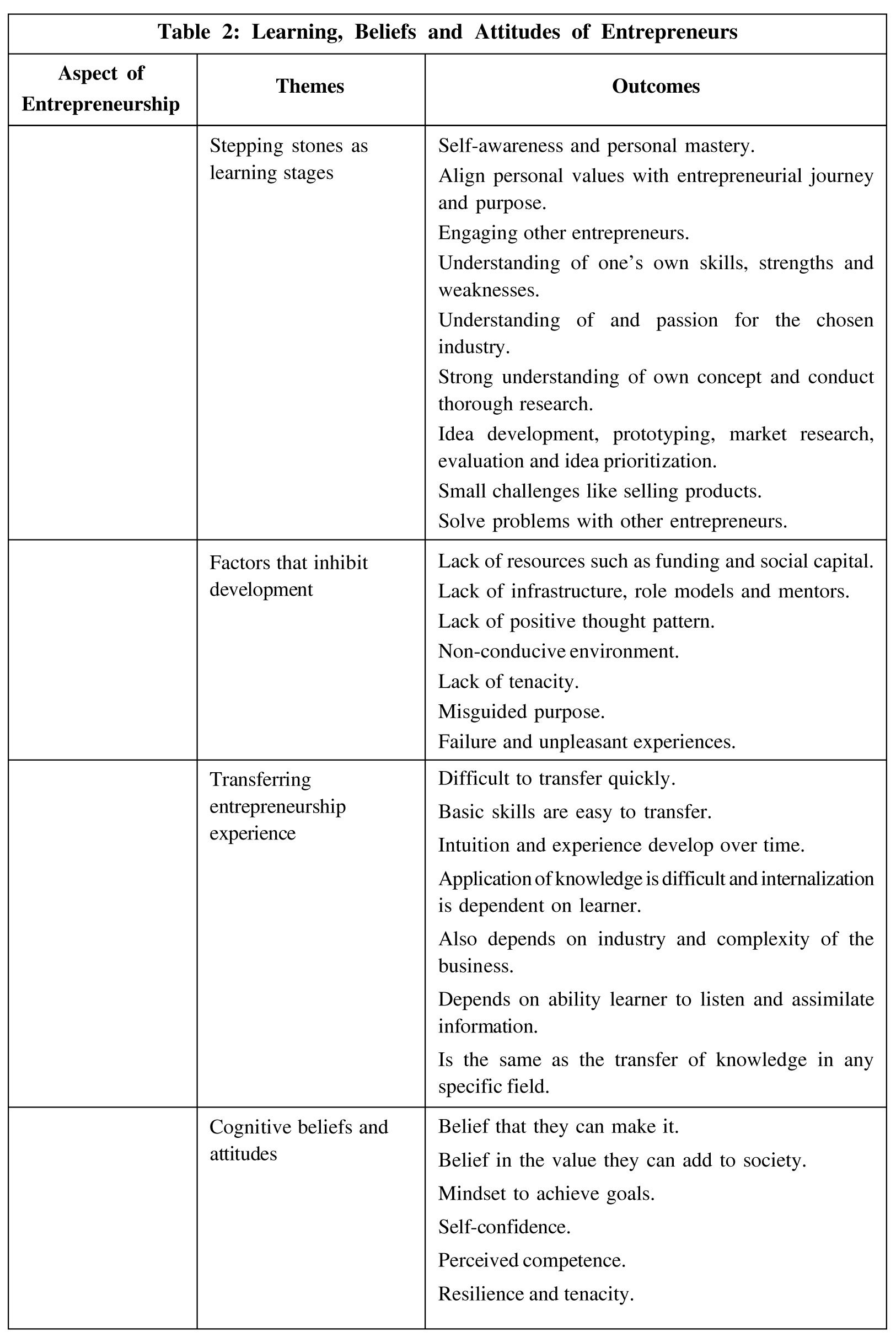

Factors That Inhibit Development

The most obvious reasons are lack of resources such as funding or a non-existent social capital. The other reasons relate to lack of access to safety nets such as support systems to see the process through. There may be lack of infrastructure, absence of role models and mentors in entrepreneurship. Commonly, novice entrepreneurs do not have the experience that will get them through the journey. Mostly, it is lack of self-awareness, leadership, mentorship and creative solutions to problems. Lack of tenacity inhibits growth of some entrepreneurs. Some give up on the first hurdle they come across as entrepreneurs.

Entrepreneurs fail, give up and run out of time and money. However, they hardly lose their entrepreneurial spirit. Most failed entrepreneurs have either run out of time or money. Entrepreneurs usually have access to a limited amount of time and money or funding. Entrepreneurs need exposure to enabling environments where they can learn, just like when a baby learns to walk, at times held by hand and progressively allowed to walk unaided. It is also possible to learn how it is done by just observing and learning from the experiences of experts. The speed of learning is accelerated through exposure to entrepreneurial or innovative environments.

Transferring Entrepreneurship Experience

The transfer of basic knowledge such as generating an idea, evaluating an idea, developing a business plan and finance is easy. One participant identified three groups of entrepreneurs, mainly those with ideas, those with technical skill that try to build a business around it and those with managerial skill that try to organize activity. Entrepreneurs can learn quickly if they pay attention to detail, do not rush, make calculated decisions and quick evaluations first, and approach entrepreneurship with wisdom and intelligence.

Another respondent also noted that it depends on whether a novice is amenable to teaching or not. Entrepreneurs are always hungry for knowledge, thus, people who are not teachable are not entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurs are eager to know more and find better ways of doing things. The novice has to be able to listen and assimilate information. The act of transferring entrepreneurship expertise is as relatively easy or difficult as transferring any other expertise. Ideally, it should be equally difficult or equally easy to transfer entrepreneurship expertise, for example, as it is to acquire accounting expertise.

Cognitive Beliefs and Opportunities

Entrepreneurs believe in their capabilities and that they can achieve their desired goals. They possess the ability to see the end goal before they achieve it. Entrepreneurs believe in the value they can add to the industry, sector and society. Entrepreneurs may neglect to evaluate and assess ideas, premises and assumptions while relying on untested information. They may neglect to test the idea and the market. They may develop ideas as if they work in vacuums while making unrealistic forecasts and timelines. Some entrepreneurs just lack perseverance. They may also lack the flexibility and willingness to make changes.

The beliefs may also vary by nation, affiliation and by customer. It helps to have shared values with those you are trying to do business with. Some beliefs may be liberating, and some may be limiting. Beliefs relating to confidence, competence or perceived competence are critical. Entrepreneurs have the resilience and the belief that despite any failures they will eventually reach their goals. The way you perceive opportunities and being available and sharing opportunities with other tends to open up more opportunities. It may be a belief that there are abundant opportunities out there or you will meet the right people, or you will be in the right place.

Expertise of the Entrepreneurs

Clues, Interpretation and Perspective of Expert Entrepreneurs

Experts are more conscious of the people around, their values and aspirations. Novices will tend to view problems from the surface, do the pitch and look at the numbers. Experts have the experience of knowing when to take a particular action in a negotiation process and picking up clues regarding decisions such as closing the deal, pushing for payment or to draw the line. Experts have managed to turn the art of identifying opportunities and interpreting scenarios into a habit. Expert entrepreneurs get better at picking up cues and anticipate outcomes.

Expertise and Opportunity Recognition

Experienced entrepreneurs may easily identify multiple opportunities within their industry. So, it is not just the experience of the entrepreneur but also experience within a particular industry that is important. An understanding of the culture and context within a specific environment also helps to uncover opportunities. It also depends on the context; certain sectors or scenarios require expertise. A set of skills is necessary for certain projects, for example, in software development. It is a matter of exposure and gaining experience in interacting with people and generating ideas. Some opportunities are in the periphery or there may be related opportunities.

A respondent ascertained that entrepreneurs do not need a certain level of expertise to recognize opportunities. All that is needed is an innovative mind and entrepreneurial mindset. It also depends on the prevailing circumstances; the same situation can be encountered by a number of people, with only some recognizing the opportunity. The recognition of opportunities is related to the entrepreneurs' positioning and focus. While some will see limitations and problems to complain about, some will see potential and challenges to be taken advantage of.

There is a shift away from culture into the realm of ethics and to some extent the world view. This may also be linked to selflessness, the ability to collaborate and a better understanding of the people. Expert entrepreneurs can define situations differently. This is influenced by experience, and problem-solving skills which improve with repeated exposure to an activity. Experts can recall and use lessons from previous experiences on how to tackle a current problem compared to novices who may not have the experience to help interpret a problem in a more representative manner.

Experts, Complexity and Sophistication of Opportunities

Intuitively experts identify more complex opportunities, but a certain level of expertise and insight is also necessary. This was confirmed by another respondent who pointed out that experts will generally gravitate to bigger problems. They consider a broad set of factors that may be involved in a particular opportunity leading to a richer business concept and creating a better business selling proposition. Experts will approach problems in a far more analytical manner and will have a wealth of knowledge to apply.

While an ordinary person or layman may approach a business or scenario as a customer or user, experts have a different perspective. At times, it takes someone with a broad, detached or fresh view to come up with meaningful innovation. The generation of ideas and innovation can be enhanced by bringing together experts from different fields or disciplines. Occasionally, novices can bring new perspective and identify opportunities that have been missed by experienced entrepreneurs. Experience builds the resilience that is necessary to keep trying despite failures and challenges.

Expertise and Opportunities: There was a view that novices should be able to work on the opportunities that are surfaced by experts. The expert would have had a holistic approach to the problem and has context while the novice will only see the opportunity on paper without full context or awareness of how the situation will unfold. It may work with the assistance of a mentor and peer group but not on their own. It will still be challenging for a novice compared to if the expert would do the implementation by themselves.

While one participant agreed that the guidance that experts provide to the novices gives them the necessary experience and attitude, it was pointed out that it may be difficult for experts to pass work on to the novices. There is a potential for gaps in communication and understanding. There may be difficulty in communicating concepts and things that do not yet exist. It also depends on the ability of the expert and novice entrepreneur to work together and have a work relationship. The environment and complexity of the work may also have an impact. It is not uncommon in innovative disruptive businesses for experts to unearth opportunities for the novices to implement. It was also recognized that there are cases of novices building successful businesses by themselves.

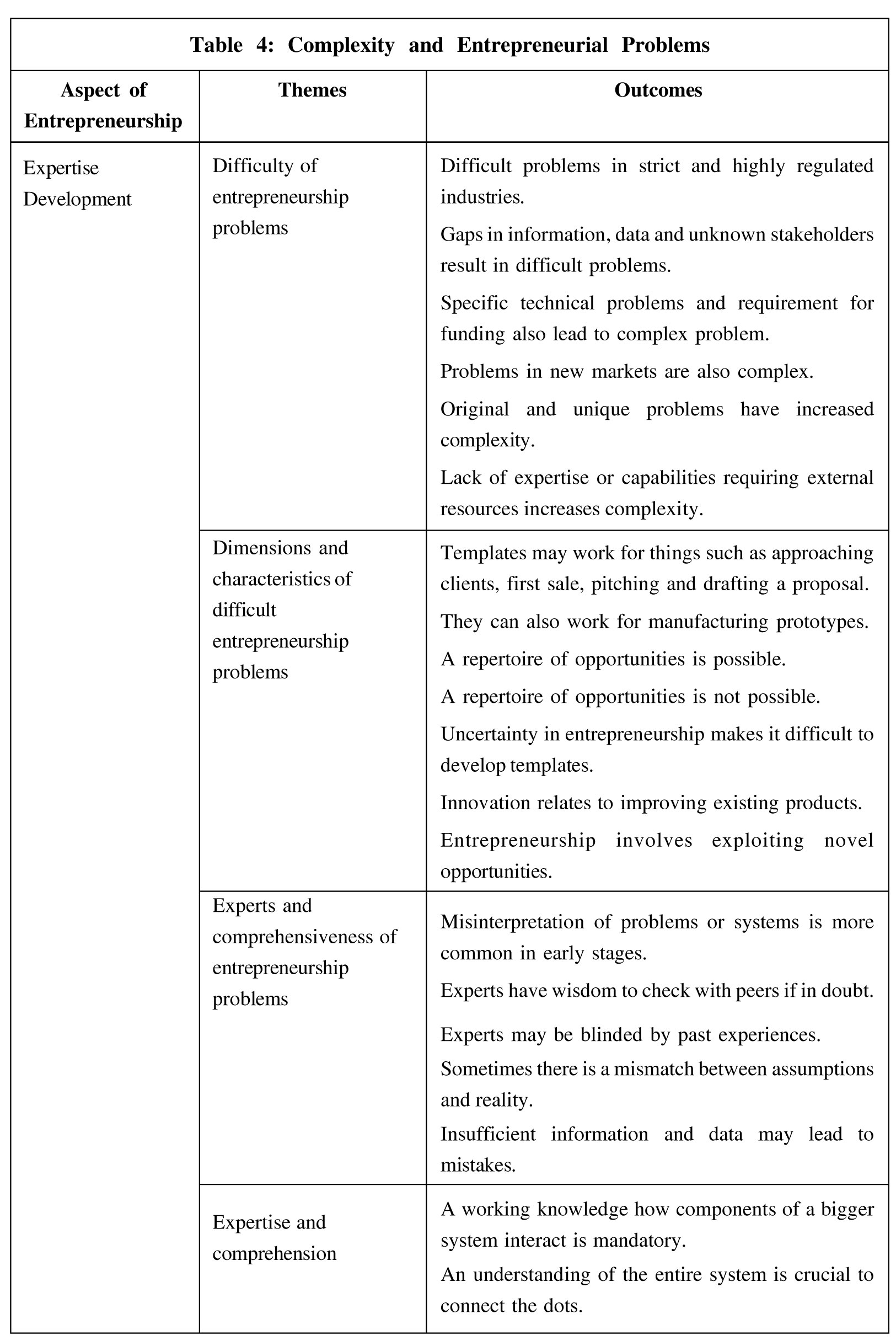

Entrepreneurship Problem Difficulty

One participant identified issues such as marketing as constituting easy problems while problems in specific technical fields together with associated needs for funding are complex. The need for more capital and involvement of more stakeholders adds complexity to problems. According to another participant, difficult problems involve solving problems that have not been solved or tapping into untapped markets. Sometimes, it depends on whether the market or customer base already exists. Simply introducing a new product to an existing business and existing customer base is easy.

A difficult problem entails something that has never been done or tested, a brand-new idea or product. These products or ideas must still be developed from the ground up, tested in the market, and the market has never seen the products before. The market has never experienced or realized the need for product before. Easy entrepreneurship problems do not require a lot of outside help, they can be executed using the resources and abilities that are available at your disposal. Difficult problems require a lot of other stakeholders and external help for execution to be possible. A new level of complexity is introduced if you need approval from several other people and assistance from others because they should all buy into the idea.

The Dimensions and Characteristics of Entrepreneurship Problems and Projects

It was pointed out that the degree of uncertainty involved in entrepreneurship adds complexity to the entrepreneurship problems. The difficulty increases with uncertainty. There are some templates that can be applied, for example, on how to deal with barriers when approaching clients. Templates for things such as doing the first sale, face-to-face, pitching for the first time, drafting a proposal or manufacturing the first prototype are also possible. In addition, a repertoire of experiences can be built but it is not clear if a repertoire of opportunities can be built.

Current opportunities may not be opportunities the following day since industries and the landscape keep changing. Experience is more stable and stays the same across different industries and is still applicable at different times. Similarly, an innovative idea is no longer innovative once it has been done therefore a repertoire of innovations will become redundant. A repertoire of innovation may assist those who are highly innovative or businesses that are constantly coming up with new products or concepts.

Expertise and Comprehensiveness of Interpretation

Commonly, a lot of assumptions about an idea and how it fits in the ideal world are made. At times, there will be a mismatch between the assumptions and reality when it comes to execution. This usually happens as a consequence of not collecting sufficient information about the problem that has been presented. Occasionally, this may result from a complete misunderstanding of the challenge that has been presented. Often problems are dismissed or ignored. It still happens that systems are misinterpreted but less frequently than in the early stages. One develops the wisdom to check with peers if in doubt and not only rely on ones' interpretation alone.

The misinterpretation of problems is in a sense an integral part of being an entrepreneur. The frequency of mistakes, like misinterpretation, has decreased as the entrepreneurs gain experience. Entrepreneurs learn important processes like screening ideas, assessing and evaluating work and ideas including testing the ground before taking a step just like when navigating a mine field. Entrepreneurs learn to better identify opportunities and to improve opportunity identification through better testing. There is an opportunity to learn from ideas that fail to get off the ground; lessons can be derived from why they failed.

Expertise and Comprehension

It is important to understand the components of a system since everything in a system is typically connected. One respondent defined it as an ability of an entrepreneur to have a helicopter view of how the different parts of a company, industry and sector work. The purpose of the system, its elements and how they impact on each other ought to be understood. The different elements of a system should be unpacked for optimal functioning.

Entrepreneurs must be able to design and implement effective systems and understand everything that goes on in the business. There should be a willingness to learn different things, listen to different people and try different things. Entrepreneurs can learn how systems work by getting involved and by doing research. Better insights are gained by being in a system. It will be difficult to join the dots without a systematic and structured approach to a problem.

Discussion

Cognitive Development of Entrepreneurs

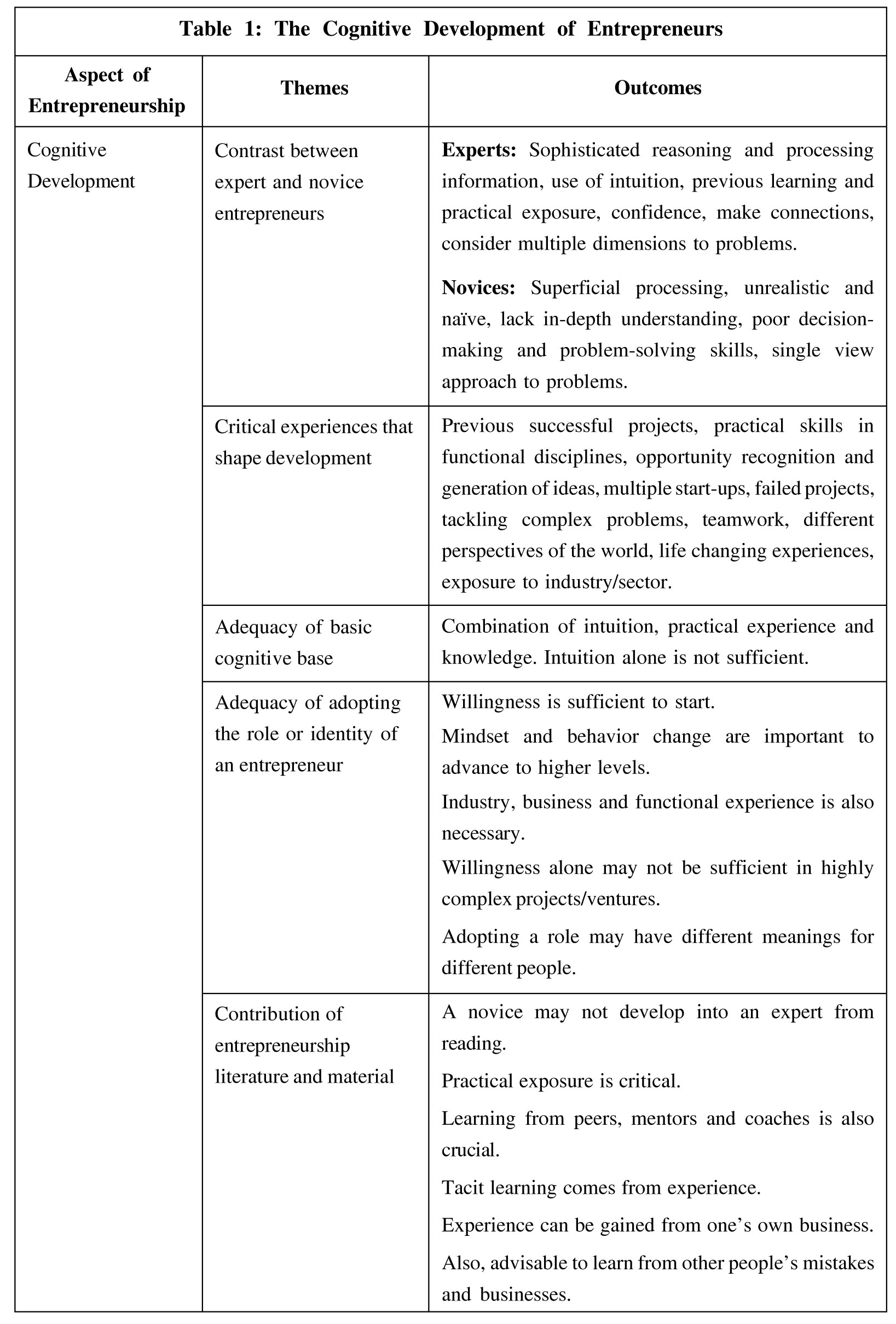

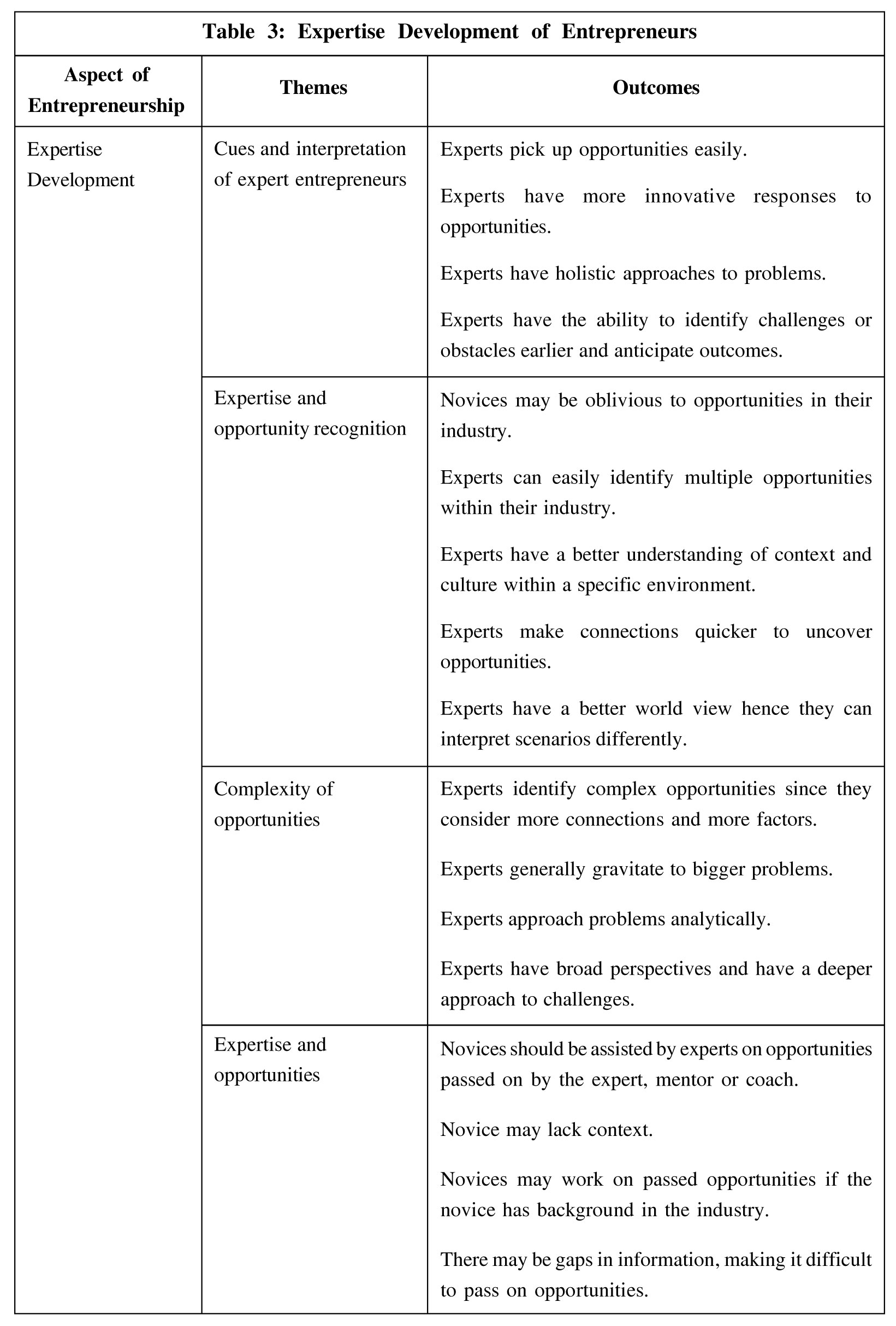

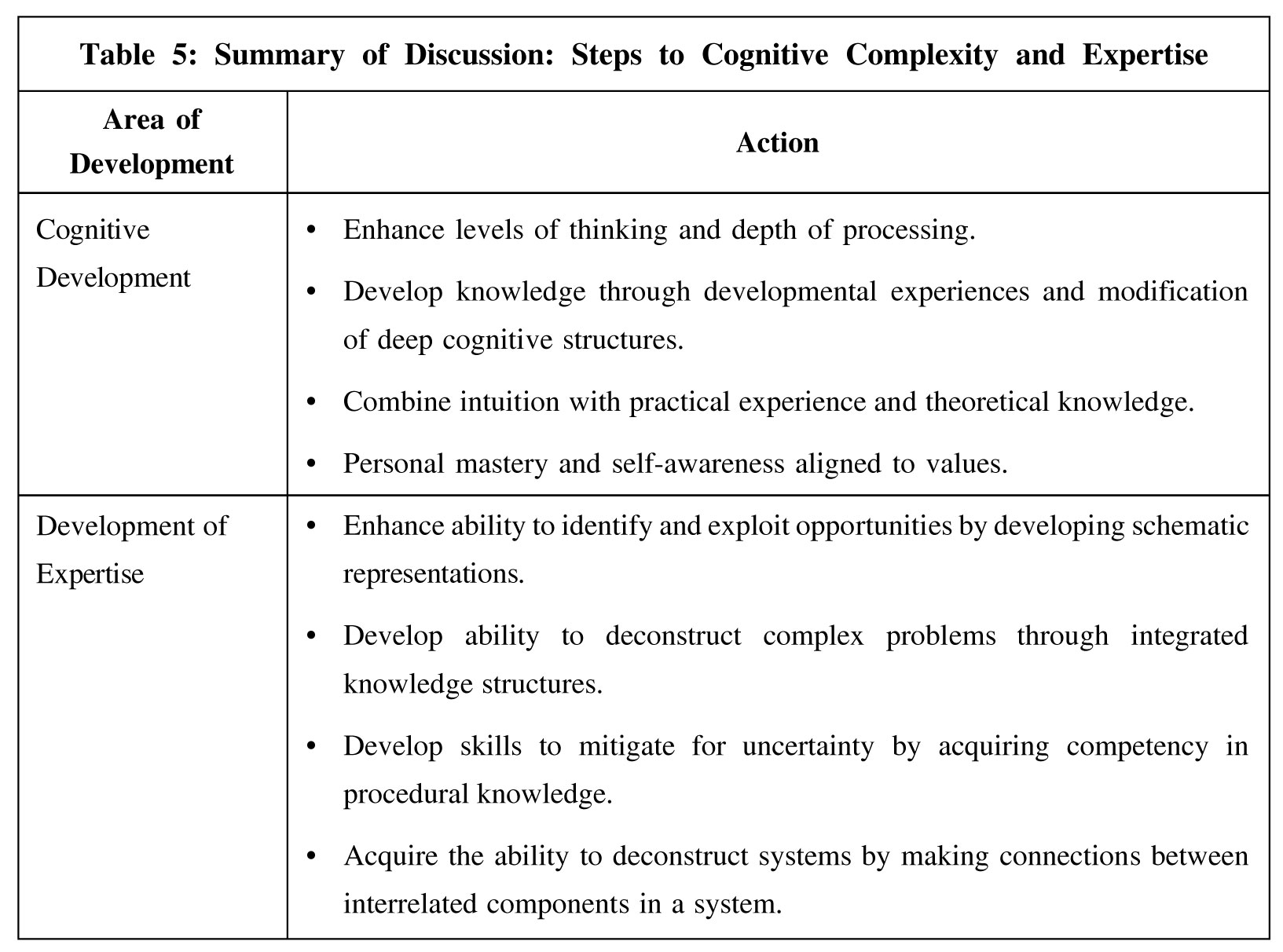

Experienced Entrepreneurs Have Superior Cognitive Structures: While expert entrepreneurs and novice entrepreneurs have the same type of thinking, they differ in the quality of thinking. The contrasts between experts and novice entrepreneurs is presented in Table 1. Experienced entrepreneurs tend to exhibit a high level of thinking in terms of content and structure. This is because experts have a well-developed working memory and constructs of reasoning. Furthermore, experts possess the ability to deconstruct complex concepts into simplified and easily manageable elements (Halford et al., 2007).

Experts also have the added advantage of applying experience to apply deeper and more sophisticated levels of processing information and make connections with expediency (Mann et al., 2009). Novice entrepreneurs are unaware of the depth of processing required to generate and process ideas. Development can be enhanced through willingness to learn, acknowledgment gaps in knowledge and curiosity. Experts have mastered mistakes through experience.

Prior Learning Enhances Cognitive Development: The factors that are important for cognitive development include the ability to learn from mistakes and practice reflection (Mann et al., 2009). The participants emphasized the importance of learning through reflection and a positive criticism of mistakes. Furthermore, learning can also be facilitated through exposure to projects and collaboration. Krueger (2007b) ascertained that the modification of perception of the world is attained through developmental experiences.

Table 1 summarizes the critical experiences and basic cognitive base that shape the development of entrepreneurs.

Development Is Linked to the Psychological State of Entrepreneurs: The development of novice entrepreneurs can be achieved by combining intuition with practical experience and

theoretical knowledge. Intuition confers the ability to have self-confidence and the trust in the capabilities to succeed as an entrepreneur (Sarasvathy, 2009). Depending on individual personality traits some entrepreneurs will have better intuition than others, thus making them better at sensing outcomes (Mitchell et al., 2000).

Role Modeling Has a Limited Role on Development: While willingness is sufficient to start as an innovator or entrepreneur, it is the mindset and the associated behavior change that is important to advance to higher levels. Prensky (2003) argued that there are similarities between entrepreneurs and digital game players where the role of internal motivation is indicative of self-directed learning. Willingness should be viewed in the context of passion, attitude and perseverance for a novice entrepreneur. This has to be supported by exposure to industry, business management and functional experience. Some of the outcomes that are deemed to be associated with the adoption of role modeling are listed in Table 1.

Practice is Essential for Cognitive Development: Immersion into the culture of entrepreneurship will yield a comprehensive learning experience compared to reading alone (Krueger 2007b). Novice entrepreneurs can have an all-encompassing learning experience by combining reading with interacting and engaging with peers, mentors, coaches and getting involved in projects. This will enhance both tacit and explicit learning experience of novice entrepreneurs. According to some participants, learning from stimulating experiences such as games that mimic real life challenges is also valuable.

Cognitive Development of Entrepreneurs Requires a Tailor-Made Approach: The educational needs of entrepreneurs should be viewed in the context of specific individual requirements and the difference between advanced entrepreneurs and beginners. Collins and Evans (2008) noted the mismatch silence that may arise as a result of failure to appreciate the needs of a learner or the inability of a learner to elicit the appropriate information from the expert. Some of the elementary ways to develop expertise include formal education, incubators and skills development programs. As part of an immersion into entrepreneurship culture, novices should also attend industry events, affiliate with the relevant associations and professional bodies. The domain-specific cultural and behavioral dispositions that are integral to expertise can be acquired passively through socialization within expert groups (Collins and Evans, 2008).