June'20

The IUP Journal of Entrepreneurship Development

Archives

Entrepreneurial Development Among Dalits: A Mixture of State Interventions and Personal Capabilities

Devendra Jarwal

Assistant Professor, Department of Commerce, Motilal Nehru College, University of Delhi, Delhi, India; and

is the corresponding author. E-mail: devendra.jarwal@mln.du.ac.in

Anju Kahal

Assistant Professor, Department of Commerce, Motilal Nehru College, University of Delhi, Delhi, India.

E-mail: anjukahal74@gmail.com

Equal development of every section of society is essential for the overall prosperity of any nation. But inequality exists in every society and things get worse when inequality of any group is caused by social discrimination. In India, historically 'Dalits' were subjected to social exclusion, but emerging market opportunities are opening avenues for Dalits as well to achieve equal economic status. Due to constitutional obligations, various Dalit empowerment schemes have also been introduced by the State. These State interventions have developed a negative sense against Dalits that they are surviving in business just because of State support system and they lack capabilities. Therefore, this study has been carried out with the objective to determine whether Dalits are in business just because of State interventions or whether they possess any individual attributes to perform on their own. The study uses the purposive sampling method for the collection of primary data and standard deviation based test of hypothesis. The authors conclude that Dalit entrepreneurship needs both State interventions through supportive policies and development programs. Individual entrepreneurial attributes of Dalits should also be acknowledged and their capabilities are required to be sharpened through State-supported entrepreneurial framework.

Introduction

Dalits, constitutionally known as scheduled caste people, had been subjected to social

exclusion and inhumanly treated as 'untouchables'. They were forced to perform leather and

sanitation works according to the status of their birth instead of skill sets. The untouchable

status had been assigned due to their historic occupational inheritance, which was the

outcome of the rigid division of labor prevalent in the Hindu religion (Kumar, 2014). Dalits were forced to carry low order works such as manual scavenging, drain cleaning, sweeping

roads, collecting garbage, tanning, etc. (Loctefeld, 2001). Thus, all external factors suppressed

the evolution of entrepreneurial capabilities amongst Dalits by just forcing them to carry out

dirty works and imposing social exclusion upon them to prevent them from carrying out any

other activities beyond the purview of their designated caste (Mander, 2006). After the

adoption of the Constitution of India, the right to equality and right to fair chances in public

employment were guaranteed to sections of the society including Dalits (Hanchinamani,

2001). Reservation in public employment is a great idea, but shrinking public sector

enterprises and policymakers' thrust to create job providers instead of job seekers have posed

a challenge to the Dalit members in seeking a career path in the capitalist private sector

(Teltumbde, 2013).

The conspicuous uplifting process of Dalits started with the liberalization of the economy,

where value and cost of a product are preferred to caste, due to which consequently a new

class of entrepreneurs emerged, known as 'Dalit entrepreneurs' (Damodaran, 2008). Internal

zeal was always present amongst Dalits to take entrepreneurial activities, but it was the

external environment that was resisting them from entering into entrepreneurship (Michael,

2007). Under the external environment, the most notable is a positive environment created

by government policies like the prohibition of discrimination, provision of finance, selfemployment

schemes for Dalits, and reservation in public sector undertaking distributorship,

etc. All these government schemes have benefitted Dalit entrepreneurs, but there is a negative

sense that has developed amongst the general public that Dalits are not talented as they lack

merit and because of government support only they are thriving (Ratnamala and Govindaraju,

2012). Thus, it would be interesting to determine the extent of the role of government schemes

in the performance of the Dalit entrepreneurs. There should be a systematic study to answer

these two research questions. Are Dalits thriving just because of excessive government

support? Are their capabilities irrelevant in determining their performance?

The answers to the above-mentioned two questions are very much important because Dalit

entrepreneurship in not only individual or family-centric, rather it affects the society and

economy at large (Zoltan et al., 2015). For economic growth, the development of every

section of society is imperative. There is no doubt that government programs are playing an

important role in uplifting the marginalized community, but in return their successful business

ventures are equally contributing to the society and economy by fulfilling consumer demands

through their products and services, paying taxes, disbursing wages, procuring raw material,

investing capital and generating gross domestic product to the nation (Izhar et al., 2015).

Most importantly, there is a need to bust the myth that Dalits lack merit and capabilities and

consequently to establish the fact that they are as capable as other human beings.

Literature Review

A huge number of existing studies on entrepreneurship have determined the various personal

attributes of entrepreneurs (Fereidouni et al., 2010). Entrepreneurs generally possess attributes

such as innovation, optimism, ability to take risks, ambition, target orientation, skill sets, education, social networking, family background, etc. (Tan, 2001; Taormina and Lao, 2007;

and Gupta and York, 2008). An entrepreneur is a person who is ready to take the risk of

establishing a new venture through his/her innovative idea to correct demand-supply

mismatch and simply exploit market opportunities for profit (Schumpeter, 1949). Schumpeter

emphasized upon the 'creative-destruction' attribute of an entrepreneur. Entrepreneurship is

about risk-taking in introducing new products or services against a product or service which

has become obsolete due to technological interventions (Drucker, 1970). Entrepreneurship is

the process of establishing a new venture or rejuvenating existing business units, especially

new business fields, by hunting for unexplored opportunities (Onuoha, 2007). An entrepreneur

is a person who consistently discovers and conceives new products or services having

identified value in response to anticipated opportunities (Bolton and Thompson, 2000). Apart

from innovation and creativity, entrepreneurs do possess the organizational capability to pool

resources, the ability to turn ideas into process, and readiness to accept failures (Hisrich,

1990). For the current study, the authors have considered the individual entrepreneurial

capabilities, and hence the data of those Dalit entrepreneurs who did not take benefit from

any direct government schemes have been separated from the total data.

The individual capabilities of an entrepreneur is also possessed by successful Dalit

entrepreneurs and some success stories have also emerged in the public domain (Kapur et al.,

2014). The book Defying the Odds is an acknowledgment of the unprecedented Dalit identity.

It narrates the outstanding success journey of 20 Dalit entrepreneurs who by dint of some

exceptional qualities like determination, aspiration, never-say-die approach, adventurism and

good luck have succeeded in overcoming the economic and social barriers. It provides some

illustrations where adversity turned into opportunities and unprecedented entry of Dalits into

avenues that were traditionally dominated by the privileged classes. These are very few

success stories, and there is still backwardness of Dalits existing in largescale due to social

exclusion by the upper caste people (Das and Mehta, 2012). Thus, external environmental

factors are the main barriers to Dalit entrepreneurship in India and in some parts of the Indian

sub-continent. The external environment to business consists of the surrounding economic

and socio-political environment (Fereidouni et al., 2010). The business environment has been

defined as the analogous durability of the administrative system conducive to the ease of

doing business (Klapper et al., 2007). Parameters for a conducive business environment

include the process of starting a business, licensing process, workers employed, property

registration process, credit facility, investor protection, taxation, free trading across borders,

contract enforcement framework, and exiting a business (World-Bank, 2020). The business

environment influences the degree of entrepreneurship and especially direct support programs

like self-employment schemes (Chatterjee and Deb, 2017).

The business environment does influence entrepreneurs in general, but in the case of Dalit

entrepreneurs, they remain insulated from taking advantage of a conducive business

environment due to social discrimination-based embargo which restricted their entry (Thorat

and Newman, 2007). The traditional caste-based retail markets did not offer much opportunity

for Dalit entrepreneurs. It was the neo-liberalized policies adopted in the year 1991 which led

open market environment and consequently the society lifted some restrictions to let Dalits enter the retail segment (Prasad and Kamle, 2012). The liberalization and privatization

policies attracted foreign capital in the country and from mixed economy setup India slightly

embraced capitalist approach which has been perceived as a transition from 'closed economy'

to the 'open economy' (Patnaik, 2016). In the open economy, price and quality of products

and services are preferred over caste and social background. Open economy eliminated the

monopolies of upper caste people and the evolution of free and fair market practices started.

The open economy accelerated fast growth which opened many new avenues for Dalit

entrepreneurs to step in (Aiyar, 2015).

To create a favorable business environment is the responsibility of the government by

providing basic facilities to the people (Van den Bosch and De Man, 1994). Efforts from the

government must be two-fold, firstly, to develop various skills among the people and

secondly, to create an economic environment to employ those skills of the people

(Richardson, 2004). The factors affecting the economic environment have already been

discussed in the previous paragraph which is being monitored under ease of doing business

initiatives. The small entrepreneur-focused basic facilities include self-employment programs,

soft terms based financial funding programs, skill development and training programs,

awareness measures, and infrastructural facilities (Vasanthakumari, 2012). The supportive role

of the government has produced promising results in the growth of entrepreneurship (Barreto,

2013). Thus, data of those Dalit entrepreneurs who did take benefit of any direct government

schemes have also been collected.

The above-reviewed literature has supported the following assumptions of this study:

- Dalits do possess entrepreneurial capabilities, but social exclusion has hindered their growth, and if free market is provided to them, they can compete with other market players fairly.

- The external environment does play an important role in entrepreneurial growth.

- The government is responsible for providing a favorable external environment conducive to business.

- The government has to play a supportive role in nurturing entrepreneurship among its people.

The reviewed literature did not provide specific answers to the above-stated two research

questions: whether Dalit entrepreneurs are thriving just because of excessive government

support and whether the capabilities of Dalits are irrelevant to the degree of their performance.

Thus, to answer both these questions, the present study has to proceed further for data

collection and apply research methodology to draw conclusions to bust the myth that Dalits

lack merit and capabilities. Conclusions may also help to establish the fact that they are as

capable as other human beings.

Data and Methodology

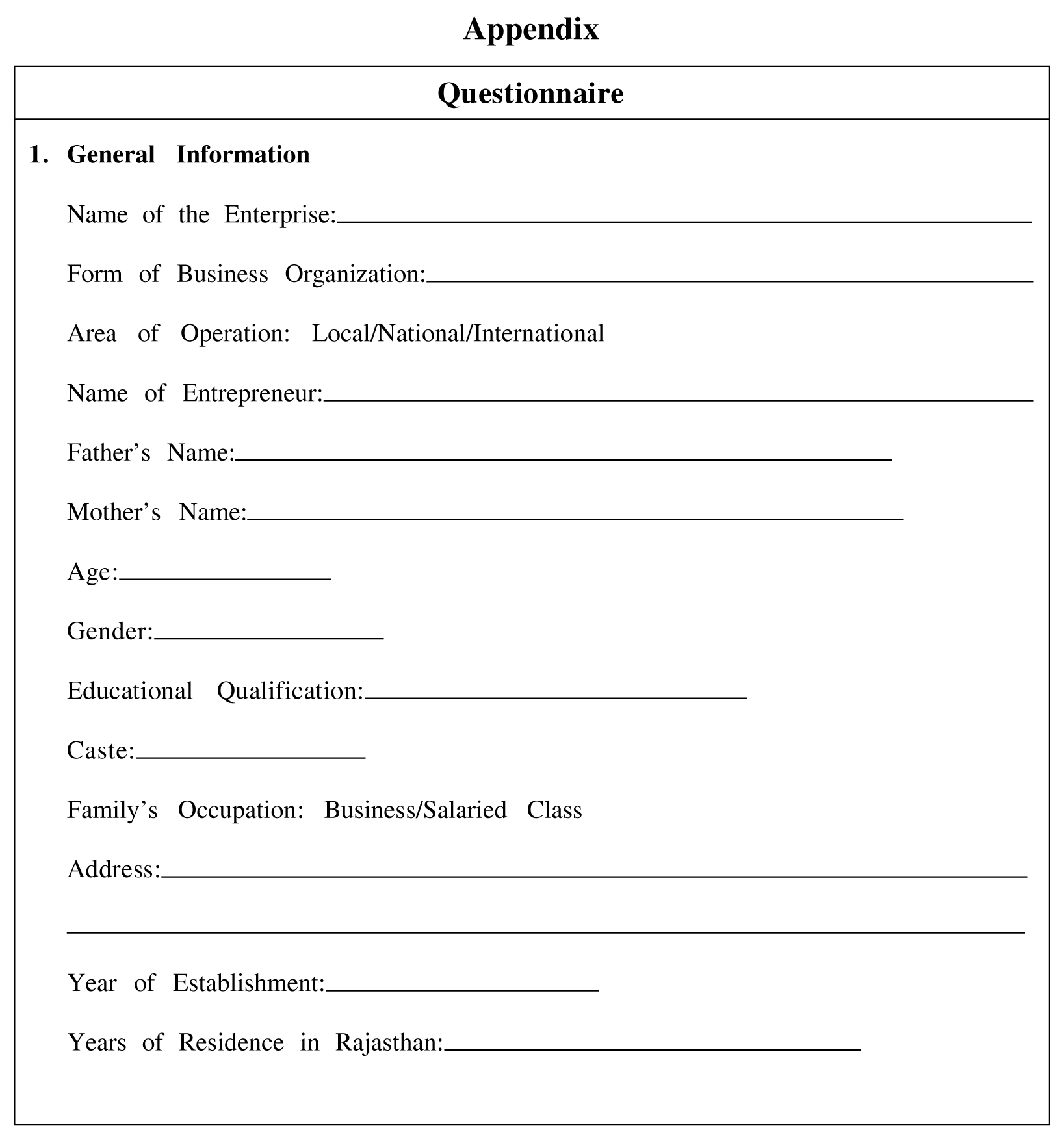

For this study, Dalit entrepreneurs operating in the state of Rajasthan have been selected for

interview. The interviews were conducted by providing a structured questionnaire (see Appendix) to the respondents and recording conversations with them while filling the

structured questionnaire. The state of Rajasthan has been chosen because it has 17.2% of the

total population consisting of scheduled caste people which is higher than the national rate

and also it has registered the highest number of atrocities against scheduled caste communities

between the years 2013 to 2015 (Bairwa, 2018). As per the Rajasthan State's economic census

report presented in the year 2005, there were 118,068 own account establishments operated

by scheduled caste persons, and in this figure of 118,068, there were 44,542 enterprises having

at least one employee hired. So the population size is 44,542 entrepreneurs. Out of this

population, 740 Dalit entrepreneurs were selected through the purposive random sampling

method and care was taken that entrepreneurs from all the districts of Rajasthan should be

represented in the survey. Out of the 740 target respondents, the authors have received

responses from 640 entrepreneurs. Statistically, for the universe population of 44,542

entrepreneurs, the authors calculated at a confidence level of 95% with confidence interval

as 4 and the resultant figure of sample size came out as 592 entrepreneurs. So the ideal sample

size is 592 entrepreneurs, while the authors got responses of 640 entrepreneurs which means

the sample size is fairly representative of the universal population of the study.

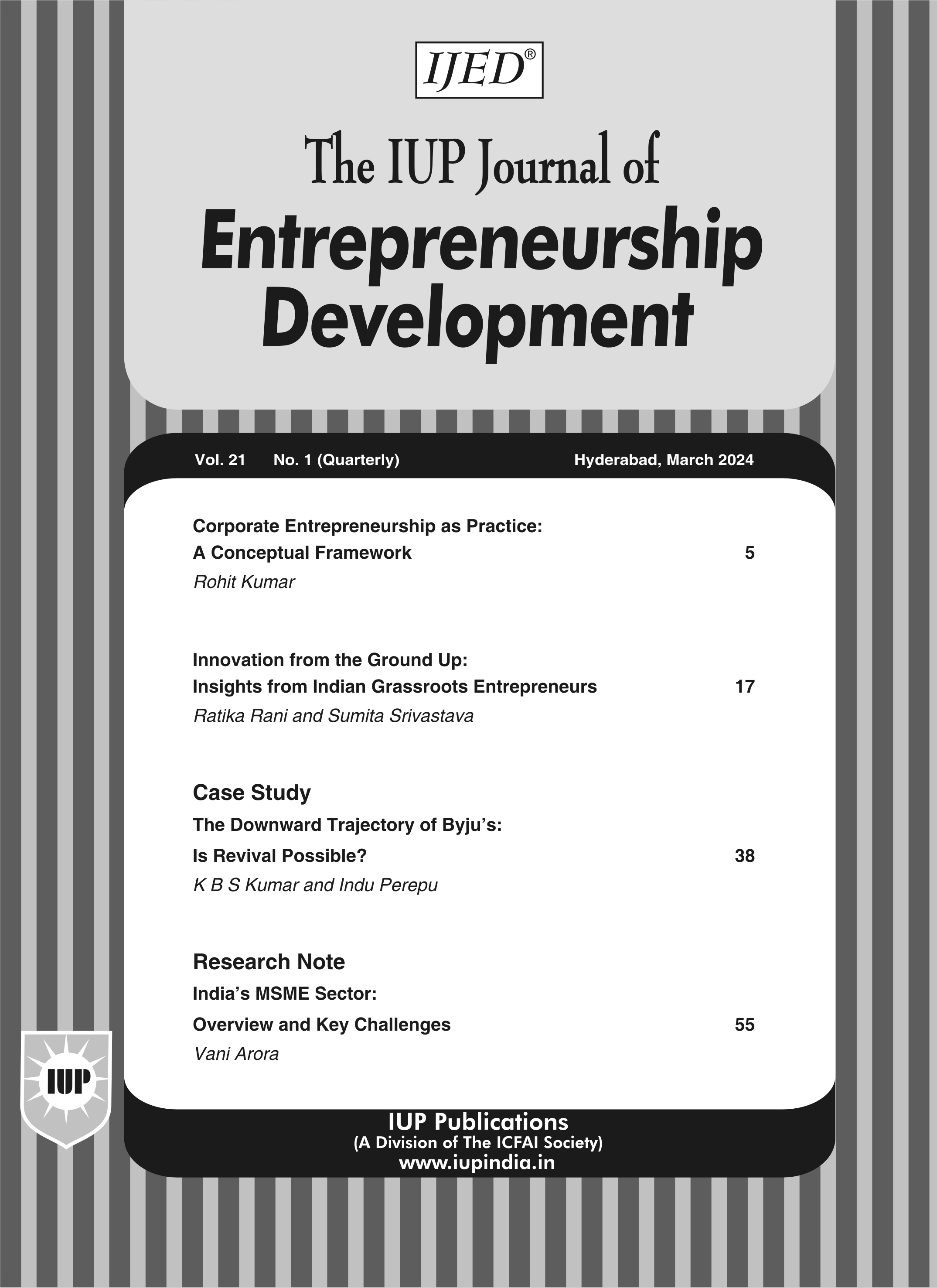

The authors have assumed both external business environment and internal capabilities

of entrepreneurs having an influence upon Dalit entrepreneurs; hence, for building a

conceptual model, the authors incorporated the theoretical framework of the Global

Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) model. The model examines the achievements of large and

big firms and also provides market opportunities to small and medium sector enterprises by

sub-contracting their orders or by procuring intermediate products from the SME firms. The

function of entrepreneurship in the enterprise creation/growth process is the main instrument

propelling macroeconomic growth which is augmented by the complementary nature of both

large and small-sized firms.

The top portion of Figure 1 focuses on the role of large established enterprises. Depending

on national framework conditions, large firms generally integrated into international trade

markets, which can promote self-expansion and maturation. The economic success of large

enterprises tends to create new market opportunities for SMEs through technological spillovers,

spin-offs, and an increase in domestic demand for goods and services, integration of

SMEs in supplier network, and so forth. Yet, whether domestic firms can seize these

opportunities depends largely on the existence of a competitive and vibrant SME sector. The

lower part of the above figure highlights the second mechanism driving economic growth:

the role of entrepreneurship in the creation and growth of firms. The entrepreneurial process

occurs in the context of a set of framework conditions. It further depends, firstly, upon the

emergence and presence of market opportunities and secondly upon the capacity, motivation,

and skills of individuals to establish firms in pursuit of those opportunities. While the success

of large established enterprises tends to create profit opportunities for small and new firms,

these firms can also affect the success of large enterprises.

In this study, the authors also found that Dalit entrepreneurs are getting business

opportunities due to vertical disintegration of manufacturing processes. The evolution of

nano-technology has led to customization of products and services. Due to the vertical

disintegration of manufacturing process and evolution of nano-technology, Dalits operating

under SMEs are getting work through sub-contracting from largescale industries (Nagraj, 1984).

Large scale industries offer standard product range and therefore SMEs are in a better position to

modify these standard products according to the needs of customers through customization process

(Fornasicro and Zangiacomi, 2013). Similarly, Dalits operating in the SME sector are getting

customization opportunities and fulfilling the customer's demand up to their expectations. The

GEM model is also helpful in testing the question whether various self-employment schemes of

the government have influenced Dalit entrepreneurship output and productivity.

H0: Various self-employment schemes of the government do not influence Dalit

entrepreneurship output and productivity.

H1: Various self-employment schemes of the government do influence Dalit

entrepreneurship output and productivity.

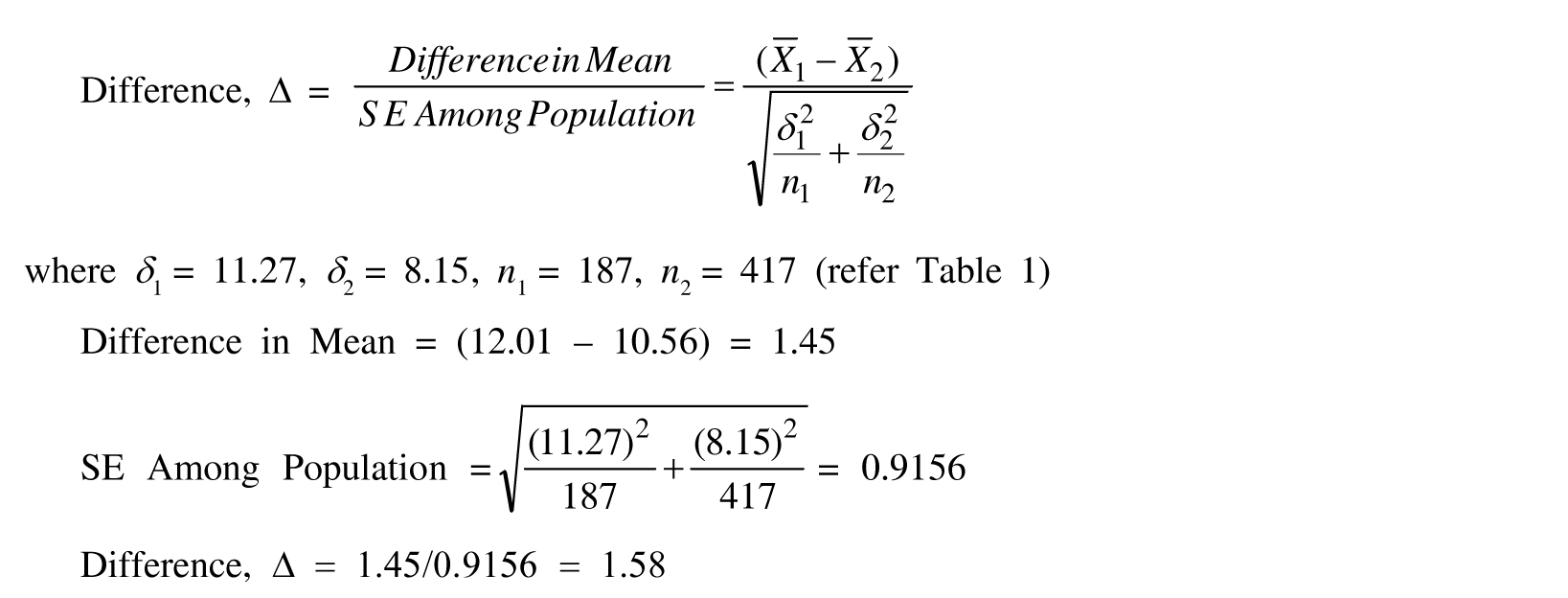

To test the significance of variables of the hypothesis, the authors have employed twotailed

tests of significance for the difference between two observed means.

Results and Discussion

To analyze the above-mentioned hypotheses, the authors filtered the data and out of a total

of 640 respondents, identified those 604 respondents who were not successors of wellestablished

business establishments and started entrepreneurial activity on their own as firstgeneration

entrepreneurs. The networth incremental rate data of entrepreneurs who had taken

benefit of self-employment schemes and also who had not taken benefit of such schemes are

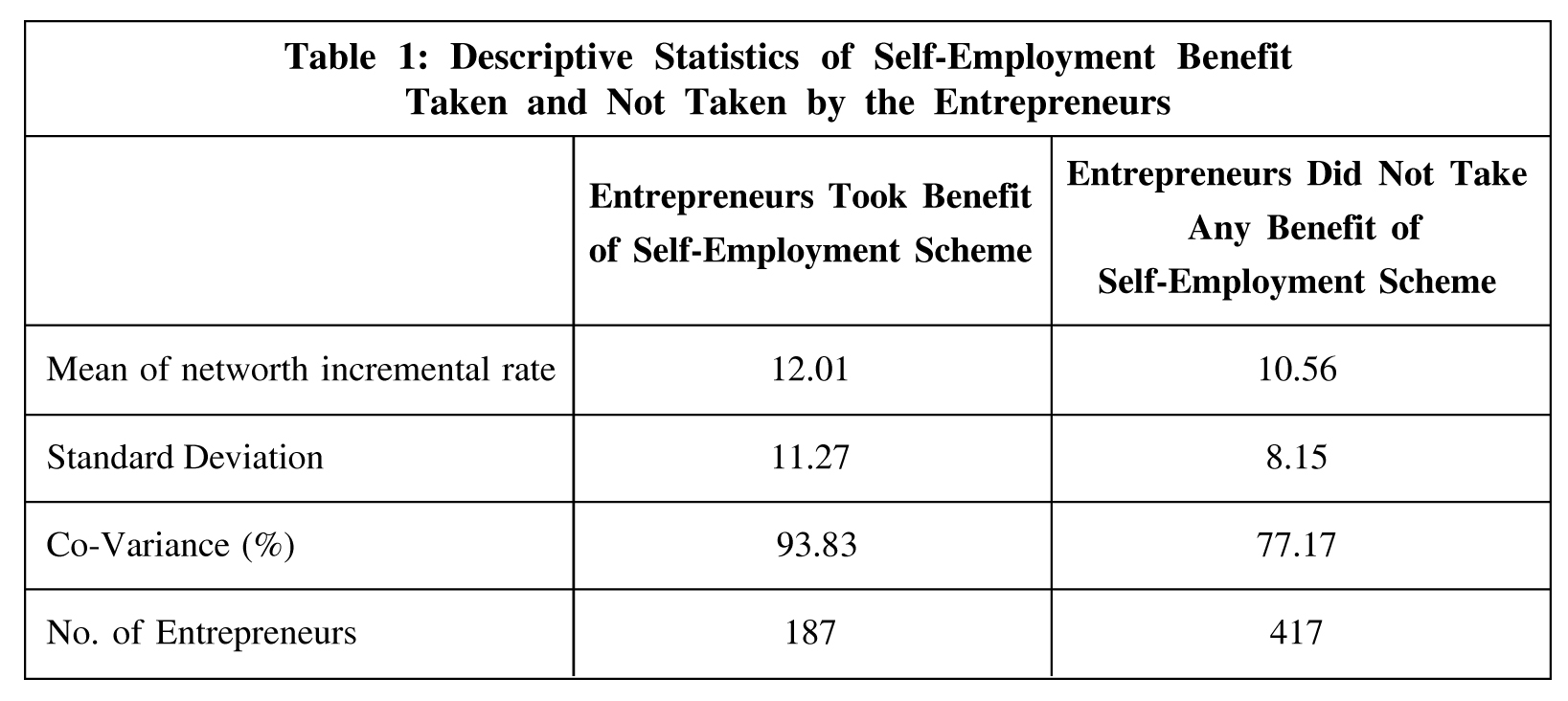

given in Table 1.

Since the difference is less than 1.96 Standard Error at a 5% significance level, the null

hypothesis is accepted. Statistically, at a 5% level of significance, if the calculated value is

less than 1.96, then there is no significant difference between the two observed means (Gupta, 2005). Hence, there is no significant difference between the performance of governmentsponsored

Dalit entrepreneurs and self-sourced Dalit entrepreneurs. However, in absolute

terms, those who have taken benefit of various self-employment schemes of the government

have registered 12.01% net worth incremental ratio which is 1.45% more than those who had

not taken any such benefits. Though entrepreneurs who had taken government-sponsored

benefits have registered more growth, yet there number is just one-third of entrepreneurs who

had not taken any benefit. Therefore, a huge number of entrepreneurs are successful not only

because of government-sponsored measures but also due to the overall liberalized

environment, i.e., they are guided by market forces and due to their entrepreneurial

capabilities. In the open market economy, the rule 'survival of the fittest' applies, and internal

capabilities of entrepreneurial firms do play an important role in combating external forces

(Behrens and Robert-Nicoud, 2014).

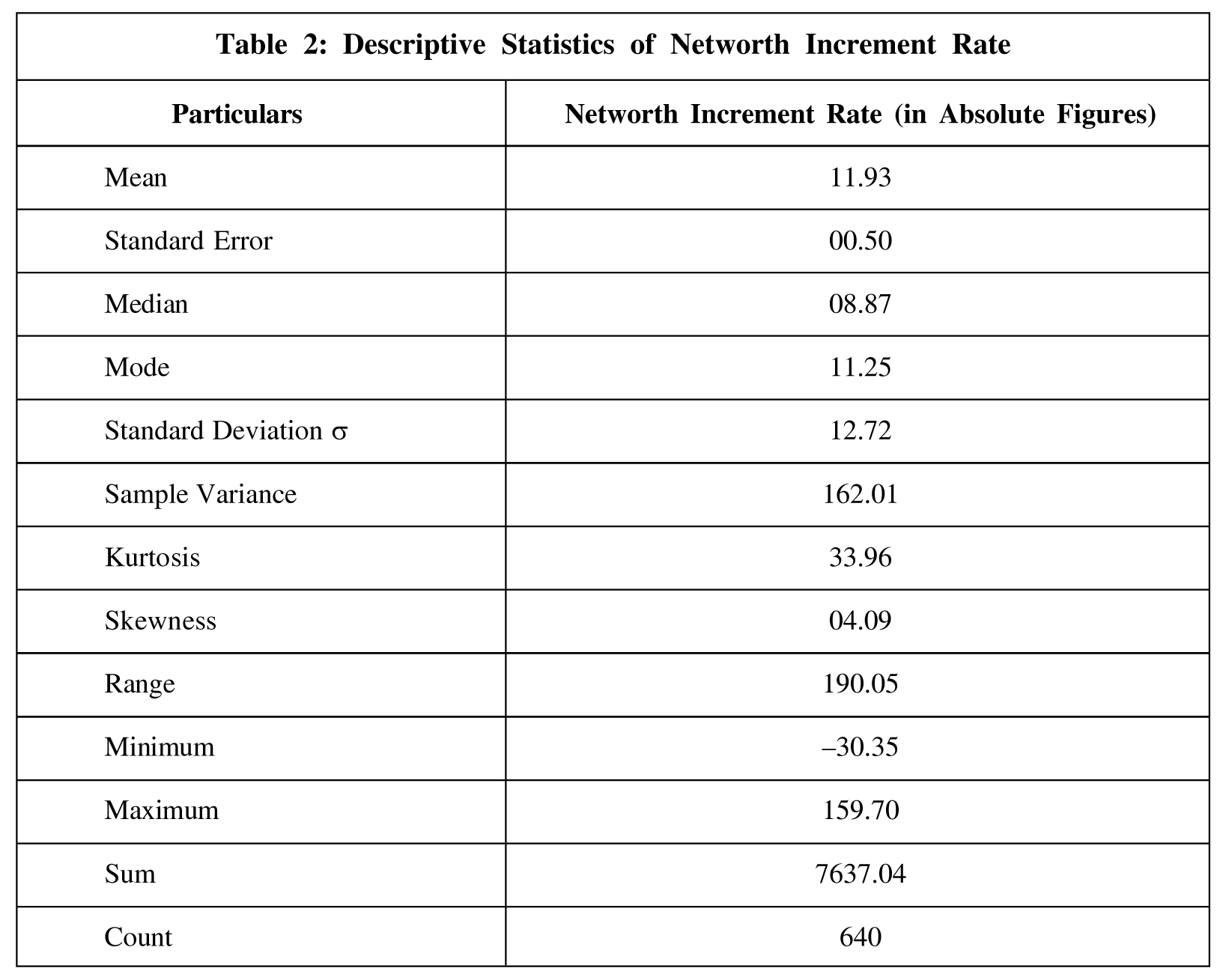

The average networth increment rate is derived from taking the compounded average

growth of capital employed registered between the periods starting from the time of

establishing business till the conclusion of immediately preceding financial year from the date

of the interview. The average capital increment ratio has been 11.93% (Table 2). The capital

increment ratio is an indicator of output and productivity (Baily et al., 1981). After analysis,

the authors found that those 187 entrepreneurs who had availed any self-employment schemes

had achieved an average capital increment ratio of 12.01%, while those 453 entrepreneurs

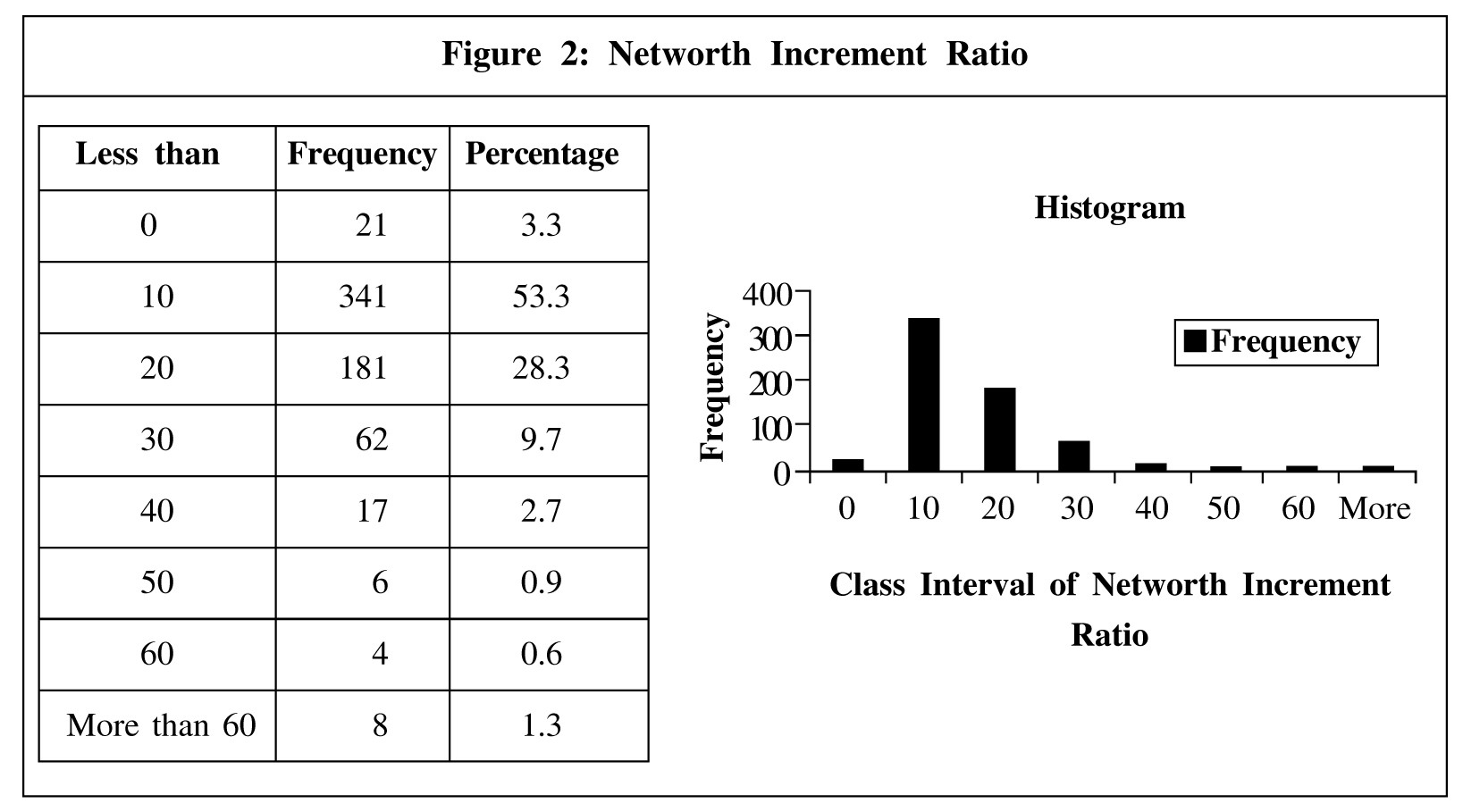

who did not avail any such schemes achieved average capital increment ratio of 11.90. With the mean at 11.93, the range of 190.05 figure is too wide and shows extreme values at lower and higher ends. However, the mode is at 11.25 which is very close to mean and distribution of frequency is Lepokurtic as kurtosis is more than 3 which shows that majority of the frequency distribution is around mean (Gupta, 2005). Skewness is also positive and this shows the movement of frequency towards the right tail and alternatively interpreting that very few firms have a negative growth rate, i.e., only 21 firms have a negative growth rate (Figure 2). Therefore, the mean of the networth increment rate is significant and fairly represents the sample population.

Question: Did you ever avail of any entrepreneurship development (with reference to specific entrepreneurship development programs such as business counseling provided by the Small Business Development Center) program? In response to this question, 134 respondents said they had availed the benefit of entrepreneurship development programs.

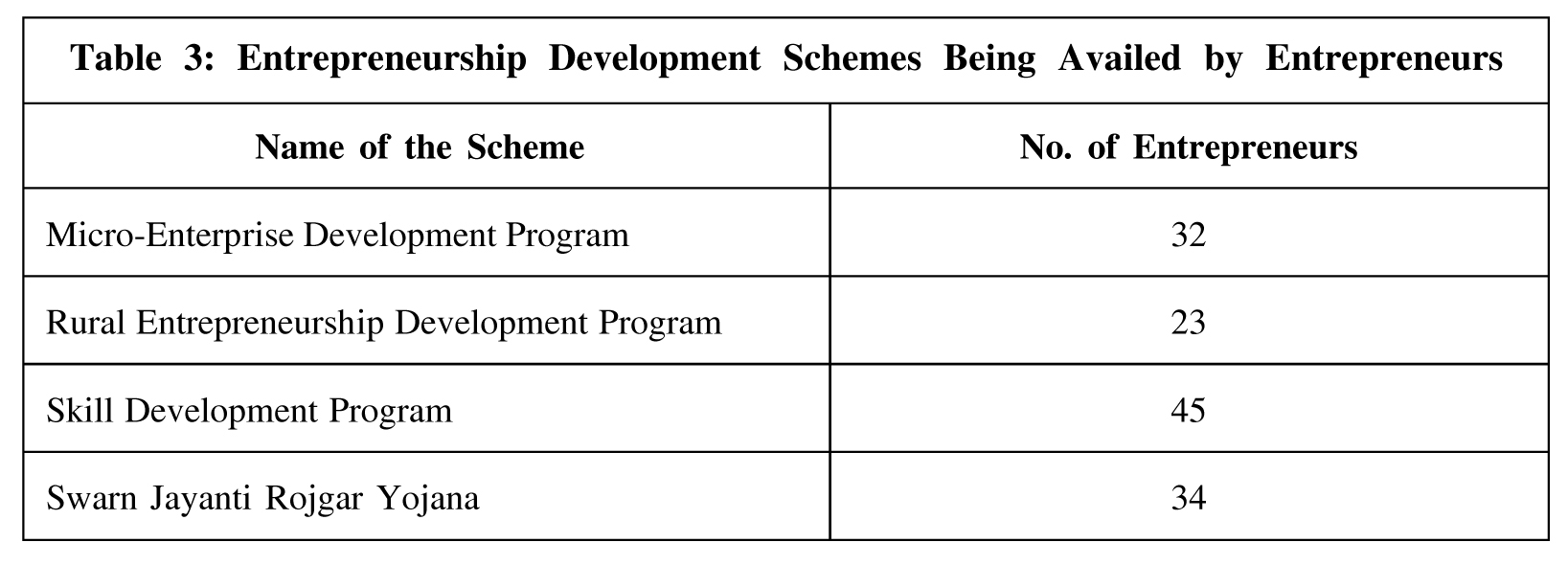

When asked to indicate any particular government schemes in the category of the

entrepreneurship development program, more than 58.20% of entrepreneurs did not respond

and skipped this question. This may be either because they were not aware of any such

schemes or because they did not find any of them useful or attractive. Of the remaining,

41.80% of entrepreneurs responded in the affirmative, and out of these respondents, 134

respondents (20.93%) did use the entrepreneurship development programs (Table 3).

Question: Have you availed of any government scheme for your business?

In the survey, the authors found that 187 out of 640 (29.21%) Dalit entrepreneurs had

availed directly or indirectly any government schemes to support their business. The majority

of them agreed that the National Scheduled Caste Finance and Development Corporation

(NSFDC) is playing an effective role in this regard. The survey also revealed that 115

(17.96%) Dalit entrepreneurs availed financial assistance under Special Central Assistance to

Scheduled Castes Sub Plan and a concessional loan from NSFDC. As per Economic Review

Report for the financial year 2014-15 of the state of Rajasthan, 49,857 Scheduled Castes

families had been assisted in the year 2013-14 against the annual target of 46.649 which was

107% of the target (Report, 2015).

In the survey, 22 (3.44%) Dalit entrepreneurs have indirectly benefitted from Self-Help

Groups (SHGs) under the Rajasthan Rural Livelihood Project. Rajasthan Rural Livelihood

Project pursues the game plan of building up the capacities of targeted households

supplemented by technical and financial support for improving incomes, minimizing costs,

cutting down risks, and reducing vulnerability. The main objective of this project is to

enhance the economic opportunities and empowerment of the rural poor with a focus on

women and marginalized groups in the 18 targeted districts in the State. Under the Project,

14,383 SHGs have been formed/co-opted till December 2014. Bank accounts have been opened

for 12,011 SHGs and Tranche-I have been provided to 8,893 SHGs, which are further assisting

marginalized groups including Scheduled Caste community members (Report, 2015).

In the survey, 38 (5.94%) Dalit entrepreneurs benefitted by the Rajasthan Scheduled

Castes and Scheduled Tribes Finance and Development Corporation Limited. It is functioning

for the welfare of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes through which the State

government has pledged to protect the economic and social concerns of these classes. Till

December 2014, a total of 7,208 persons benefitted from the banking scheme introduced under

Special Central Assistance (Report, 2015).

In the survey, 12 (1.88%) Dalit entrepreneurs have been allotted land by the Rajasthan

State Industrial Development and Investment Corporation (RIICO) under the Special Scheme.

This Special Scheme is aimed to encourage scheduled caste and scheduled tribe entrepreneurs

to set up their industrial units and special rebate at the rate of 50% in the allotment of land/

plots is facilitated by RIICO. Corporation has been making special emphasis upon SC and

ST entrepreneurs by allowing upfront concession in the rate of development charges in the

land allotment in industrial areas. During the financial year 2014-15, under Scheduled Caste

Sub Plan, RIICO gave a rebate of 2.88 mn in development charges (Report, 2015).

The survey also indicates that government schemes formulated to support business among

Dalits are vital because they lead to the formation of perception that entrepreneurship is not

only possible for people of the marginalized community but also worthwhile in improving

their status. Below are some quotes from the survey:

"As per my opinion, I think that support from government and other relevant institutions

create an environment conducive to entrepreneurship and thus stimulate entrepreneurship.

Support also indicates that business start-up is a good thing for individuals in general and

marginalized community in particular and therefore important for society. Assistance either

by way of concessions, technical training including apprenticeship and access to affordable

startup finance promotes the status of entrepreneurship among Dalits as an important

endeavor. So support matters in the intention to start a business."

"According to my experience, I can say that the government and other sister institution's

support affects the intention to start a business in many ways. Therefore, for would-be

entrepreneurs, the availability of support makes them begin to think that business startup is

achievable. I consistently noticed that there are Dalits who started their businesses because

assistance for startups became available from our institutions mostly in the case of LPG

distributorship, Petrol Pumps, and Ration Shops, etc. In other words, these Dalit individuals

would not have started if support was not available."

"Even if an individual is able to identify an opportunity that he or she believes can be

turned into a profitable business, and even if an individual is able to develop a business plan

around such an idea, he or she will not be able to make it a reality if affordable startup capital

cannot be accessed. So for me, this is a major support element that should be in place to

promote entrepreneurship."

The survey indicates that a favorable policy may promote Dalit entrepreneurship to a high

status in society and it also increases entrepreneurs' confidence by thinking that starting and

growing a business is possible for Dalits. Low cost and dedicated finance for Dalits offered

by the NSFDC have enabled and encouraged entrepreneurs who would never have considered

starting a business to have a go. The survey identified several major benefits of the support

mechanism. These benefits include simplified business regulation on business operations and

lower business formalization costs, access to markets, access to affordable low-cost finance,

counseling with training facilities and provision of accessible technology. Most of the

entrepreneurs revealed that during their startup phase, they were unable to afford business

registration fees and rent for the suitable location of the business, hence there is a need to

reduce business registration fees, business rates, and rents for new businesses. The authors also

noticed that some critical business facilitation services can only be accessed through regional

centers often located at District or Tehsil (Sub-District) headquarters. This creates a barrier

against nascent Dalit entrepreneurs because of travel cost implications and inability to hire

agents. However, the facility of e-governance is available where they can get access through

virtual mode instead of a physical visit, but still for application process, they need to visit

physically due to the ineffectiveness of the system.

In the survey, the authors found that 66 (10.31%) Dalit entrepreneurs wanted to avail but

were not successful in availing the facility of government schemes or any kind of organized

finance. Because, while a certain level of financial support is available through these schemes,

yet access is not straightforward. The procedural requirements to access debt finance are often

complicated and often require services of middleman with lots of rigid paper formalities.

Sometimes, they not only depend on whom one knows within the institution or government

but also whether one has collateral and a viable business plan. Thus only a few people may

be able to meet these conditions.

Out of the 453 respondents who were not government sponsored, 36 respondents admitted

that they were lucky as they inherited their already established family business but still they

feel homophily and social discrimination in the market. Out of those who had not taken any

direct government-sponsored benefits, they revealed their struggle stories. 196 respondents

were intrapreneur turned entrepreneurs, and saving generated from job salary was used to

establish their business. They carried the same core and allied activities of their employers,

and experience earned while in job helped them a lot in the form of apprentice training. The

remaining 221 respondents started their journey from scratch and were 'necessity

entrepreneurs' who embraced entrepreneurship due to push factors as they did not get any

meaningful employment. Their struggle in establishing business helped them as 'on the job

training'.

Conclusion

It can be concluded that there is no significant difference between the average networth

increment rate of entrepreneurs who have taken direct benefit of any government scheme and

the average networth increment rate of entrepreneurs who have not taken any direct benefit

of any government scheme. Though the average rate of net-worth increment ratio of

government-sponsored entrepreneurs is more than 1.45 than self-source-financed entrepreneurs,

yet co-variance of self-source-financed entrepreneurs is less as compared to governmentsponsored

entrepreneurs (Table 1). Therefore, the performance of self-source-financed

entrepreneurs, is more consistent as compared to government-sponsored entrepreneurs.

Moreover, in the sample data, the authors found that self-source-financed entrepreneurs

consist of more than 70% of the total sample population, which means such entrepreneurs are

much higher in number than government-sponsored entrepreneurs. Hence, government

support is imperative in the success of any Dalit entrepreneur, yet the individual capabilities

of Dalit entrepreneurs have an important role in running their business operations. With their

capabilities, they have overcome the financial, social and economic barriers (Jodka, 2010).

Dalit entrepreneurs do not operate in isolation, they also work under a system. Targeted

welfare schemes to Dalits entrepreneurs do provide benefits to them, but they are also equally

influenced by the overall business environment of the nation. If given a fair chance to play,

they will perform as good as other entrepreneurs of the nation. India is performing well by

constantly improving its tally in the ease of doing business index (Doshi et al., 2019). The

pull factors of the business environment are providing opportunities to every citizen of India

and so is the case with Dalit entrepreneurs. But due to the prevailing social discrimination against Dalits in the society, they need special attention from the policymakers. Public

employment avenues are also shrinking and there are not many employment opportunities in

the ongoing economic scenario and most of the Dalits still live below the poverty line.

Therefore, because of these push factors, Dalits have to start their own business to survive and

they require a government support system, not only financial support but the most important

discrimination-free positive environment where their capabilities get fair recognition. The

authors conclude that Dalit entrepreneurship needs both State interventions through

supportive policies and development programs and indeed it is sustaining because of both

the features i.e., State interventions and personal capabilities. Individual entrepreneurial

attributes of Dalits should be acknowledged and their capabilities sharpened through Statesupported

entrepreneurial framework.

- Aiyar Swaminathan S Anklesaria (2015), "Capitalism's Assault on the Indian Caste System: How Economic Liberalisation Spawned Low Caste Dalit Millionaires", Policy Analysis, No. 776, pp. 1-16.

- Baily Martin Neil, Robert J Gordon and Robert M Solow (1981), "Productivity and the Services of Capital and Labor", Brooking Papers on Economic Activity, No. 1, pp. 1-65, DOI:10.2307/2534396.

- Bairwa Sita Ram (2018), "Atrocities Against Dalits in Rajasthan: An Analytical Study of Dausa District", An International Journal of Research in Social Sciences, Vol. 8, No. 6, pp. 516-531.

- Barreto Humberto (2013), The Entrepreneur in Microeconomic Theory: Disappearance and Explanation, Routledge, 1821, London.

- Behrens Kristian and Robert-Nicoud Frederic (2014), "Survival of the Fittest in Cities: Urbanisation and Inequality", The Economic Journal, Vol. 124, No. 581, pp. 1371-1400.

- Bolton W K and Thompson J L (2000), Entrepreneurs: Talent, Temperament, Technique, Butterworth-Heinemann, 40, Oxford.

- Bosma Neils and Donna Kelly (2019), "Global Entrepreneurship Monitor", Global Entrepreneurship Research Monitor, 11, London.

- Chatterjee Rajesh and Deb Amit Kumar (2017), "Effect of Government Programmes on Entrepreneurship: A Study on NE India with Special Reference to Tripura", EPRA International Journal of Economic and Business Review, Vol. 5, No. 8, pp. 47-57.

- Damodaran Harish (2008), India's New Capitalists: Caste, Business, and Industry in a Modern Nation, Palgrave Macmillan, 38, New Delhi.

- Das Maitreyi Bordia and Mehta Soumya Kapoor (2012), Poverty and Social Exclusion in India: Dalits, World Bank, 2, Washington DC.

- Doshi Rush, Kelly Judith G and Simmons Beth A (2019), "The Power of Ranking: The Ease of Doing Business Indicator and Global Regulatory Behavior", International Organisation, Vol. 73, No. 3, pp. 611-643.

- Drucker Peter (1970), "Entrepreneurship in Business Enterprise", Journal of Business Policy, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 3-12.

- Fereidouni, Hassan Gholipour, Ariffin Tajul Masron et al. (2010), "Consequences of External Environment on Entrepreneurial Motivation in Iran", Asian Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 15, No. 2, pp. 175-196.

- Fornasicro Rosanna and Zangiacomi Andrea (2013), "A Structural Approach for Customised Production in SME Collaborative Networks", International Journal of Production Research, Vol. 51, No. 7, pp. 2110-2122.

- Gupta S P (2005), Statistical Methods, Sultan Chand & Sons, 910, New Delhi.

- Gupta V K and York A S (2008), "Attitudes Toward Entrepreneurship and Small Business: Findings from a Survey of Nebraska Residents and Small Business Owners", Journal of Enterprising Communities, Vol. 2, No. 4, pp. 348-366.

- Hanchinamani Bina B (2001), "Human Rights Abuses of Dalits in India: 2001", Human Rights Brief, Vol. 8, No. 2, p. 6.

- Hisrich Robert D (1990), "Entrepreneurship/Intrapreneurship", American Psychologist, Vol. 42, No. 2, pp. 209-222.

- Izhar Syed Tariq, Abdur Wajidi and Syed Shabib-ul-Hasan (2015), "Government's Role to Encourage the Growth of Entrepreneurship in Pakistan", IOSR Journal of Business and Management, Vol. 17, No. 9, pp. 28-34.

- Jodka Surinder S (2010), "Dalits in Business: Self-Employed Scheduled Castes in Northwest India", Working Paper Series, Indian Institute of Dalit Studies, 23, New Delhi.

- Kapur Devesh, Shyam D Babu and Chandra Bhan Prasad (2014), Defying the Odds: The Rise of Dalit Entrepreneurs, The Random House, 8, Gurgaon.

- Klapper Leora, Amit Raphel, Mauro F Guillen and Juan Manuel Quesada (2007), "Entrepreneurship and Firm Formation across Countries", Working Paper, World Bank Policy Research, Washington DC. 139, DOI: 10.1596/1813-9450-4313.

- Kumar Vivek (2014), "Inequality in India: Caste and Hindu Social Order", Transcience Journal of Global Studies, Vol. 5, No. 1, pp. 36-52.

- Loctefeld James G (2001), The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. 1, The Rosen Publishing Group, 15, New York.

- Mander Harsh (2006), "Unclean Occupations: Savaged by Traditions", in Ghanshyam Shah, Harsh Mander, Sukhadeo Thorat, Satish Deshpande and Amita Baviskar (Ed.), Untouchability in Rural India, 7, Sage Publications, New Delhi.

- Michael Sebastian Maria (2007), Dalits in Modern India: Vision and Values, Sage Publications, New Delhi, India, 37.

- Nagaraj R (1984), "Sub-Contracting in Indian Manufacturing Industries: Analysis, Evidence, and Issues", Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. XIX, Nos. 31, 32 & 33, pp. 1435-1453.

- Onuoha G (2007), "Entrepreneurship 2007", AIST International Journal, Vol. 10, No. 1, pp. 20-32.

- Patnaik Prabhat (2016), "Capitalism and India's Democratic Revolution", Social Scientist, Vol. 44, Nos. 1&2, pp. 3-15.

- Prasad and Kamle (2012), "Empower Dalits, Do Away with India's Antiquated Retail Trading System", The Times of India, December 5.

- Ratnamala V and P Govindaraju (2012), "Status of Dalits in Indian News Media", Mass Communications: International Journal of Communication Studies, Vol. 6, No. 3, pp. 20-23.

- Report (2015), Economic Review Report 2014-15, 35,76 & 83, Government of Rajasthan, Jaipur.

- Richardson James (2004), "Entrepreneurship and Development in Asia", International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management, Vol. 4, No. 5, pp. 469-484.

- Schumpeter Joseph (1949), Economic Theory and Entrepreneurial History, Harvard University Press, 10, Massachusetts.

- Tan J (2001), "Innovation and Risk-Taking in a Transitional Economy: A Comparative Study of Chinese Managers and Entrepreneurs", Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 16, No. 4, pp. 359-376.

- Taormina R J and Lao S K (2007), "Measuring Chinese Entrepreneurial Motivation Personality and Environmental Influences", International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research, Vol. 13, No. 4, pp. 200-221.

- Teltumbde Anand (2013), "FDI in Retail and Dalit Entrepreneurs", Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 48, No. 3, pp. 10-11.

- Thorat Sukhdeo and Newman Katherine S (2007), "Caste and Economic Discrimination: Causes, Consequences, and Remedies", Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 42, No. 41, pp. 4121-4124.

- Van den Bosch, Frans A J and Ard-Pieter De Man (1994), "Government's Impact on the Business Environment and Strategic Management", Journal of General Management, Vol. 19, No. 3, pp. 50-59.

- Vasanthakumari P (2012), "Economic Empowerment of Women Through Microenterprises in India with Special Reference to Promotional Agencies", International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 194-210.

- World-Bank (2020), Doing Business, World Bank Group, 13, Washington DC.

- Zoltan Acs J, Szerb L and Erkko Autio (2015), National System of Entrepreneurship, in Global Entrepreneurship and Development Index 2014, pp. 13-26, Springer, Cham.