September'21

The IUP Journal of Entrepreneurship Development

Archives

Finding a Green Solution to Plastic: Kevin Kumala's Cassava Bags

Munmun Samantarai

Former Research Associate, IBS Hyderabad (Under IFHE-A Deemed to be University u/s 3 of the UGC Act, 1956), Hyderabad, Telangana, India. E-mail: munmun.samantarai@gmail.com

Indu Perepu

Research Faculty, IBS Hyderabad (Under IFHE-A Deemed to be University u/s 3 of the UGC Act, 1956), Hyderabad, Telangana, India. E-mail: indup@ibsindia.org

Established in 2014, Avani Eco was spearheaded by Kevin Kumala (Kumala), an Indonesian social entrepreneur. Kumala's concern for plastic pollution and its increasing negative impact on the country drove him to look for a solution. He came up with a groundbreaking innovation with a root vegetable, cassava, to combat the plastic pollution. Avani manufactured a compostable bioplastic made from cassava starch, and also made a full range of sustainable food packaging and hospitality products from renewable resources. Its bioplastic bags gained special attention as the company claimed that the bags dissolved in water and were safe for aquatic animals and even humans. However, Avani Eco faced certain challenges. As the company did not focus much on marketing its products, not many were aware of its existence. Lack of awareness about the product made it tough for Avani to limit and replace the use of traditional plastic. Also, bioplastic was more expensive than conventional plastic, so the cost of Avani bags was higher than that of the usual plastic bags. The company was also struggling to scale up due to lack of funding. The case highlights Indonesia's fight against plastic, the journey of Avani Eco, its products, and the company's future plans to compete with traditional plastic and emerge as a 'green' replacement.

If the marine biota is destroyed, we will have to face the consequences.1

– Kevin Kumala, Chief Green Officer, Avani Eco, in 2017.

Plastic is not an intrinsically bad material, it is an invention that has changed the world. The plastic became bad due to the way that industries and governments use it.2

– World Wildlife Fund, (WWF) Report, in 2019.

Introduction

OAs the world's population increased, there was a related problem that was spiraling out of control-that of plastic waste. On-the-go lifestyles required disposable products such as plastic bottles, disposable tumblers and plates, and so on. People seemingly could not do without plastic and their addiction to single-use or disposable plastic had severe environmental consequences. Plastic bags had become a huge nuisance and were a major contributor to environmental pollution, wildlife deaths, and human health hazards. They had other detrimental impacts as well. While plastic was an incredibly useful material, it was made from toxic compounds that caused illness, and it was not biodegradable.

In June 2019, according to reports published by Switzerland-based World Wildlife Fund (WWF)3, 75% of the plastic ever produced in the world had ended up as waste and about 87% of mismanaged waste had leaked into nature and had taken the form of plastic pollution.4 In 2018, environmentalists predicted that by 2050, plastic would outweigh all the fish in the oceans.5 According to a study carried out in 2017, and a study carried out by scientists from the University of Georgia, more than 8.3 billion tons of plastic had been produced since the early 1950s. Of these, 6.3 billion tons had been discarded.6 The report also highlighted that about 60% of that plastic had either ended up in landfills or in the natural environment.

The world had finally woken up to the plastic pollution, and there were constant efforts being made to make plastic more environment-friendly. The governments of various countries, international organizations, and NGOs were keeping the spotlight trained on plastic pollution. One of the industries hit by plastic pollution was the travel and tourism industry, Indonesia's Bali, a popular tourist destination, was, for example, paying a heavy price due to plastic pollution. According to a study, Indonesia had added between 480,000 and 1.29 million metric tons of plastic waste to the oceans in 2010 due to poor waste management and littering. This had earned it the dubious distinction of being ranked second in the world, next only to China in terms of marine plastic pollution.7 With more than 80% of Indonesia's economy being dependent on tourism, the plastic strewn beaches posed a major threat to the industry.

In 2014, Kevin Kumala (Kumala), a Balinese biologist, was shocked to see the landscape in Kuta8, covered with plastic. There was no sign of the white sandy beaches and calming turquoise waters he had grown up with. This crisis prompted Kumala to establish Avani Eco (Avani), to create a better plastic that would leave no trace on earth. "It was just so obvious that the opportunity to do something was so wide open. The goal was always to find a potential replacement for these disposable plastic products."9

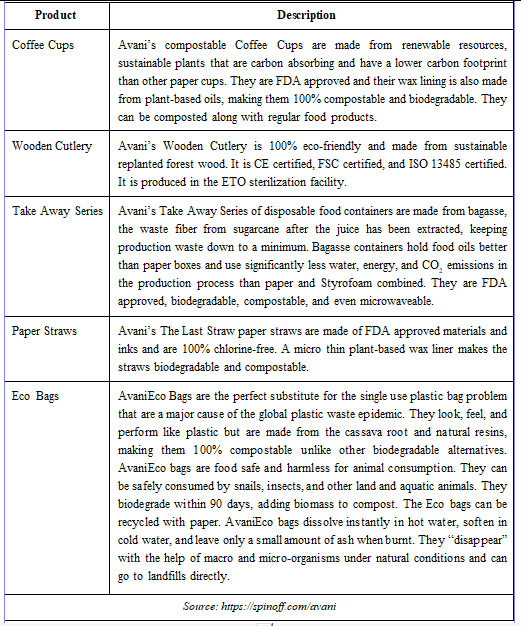

Kumala found a solution in the form of cassava10, vegetable oil, and organic resins. Since 2015, Avani had produced all kinds of disposable and eco-friendly products including coffee cups, cutlery, food containers and straws, and cassava plastic ponchos, and designed 100% biodegradable bags made from cassava starch.

In January 2017, Kumala came up with another groundbreaking innovation-a 'drinkable' plastic bag. Wanting to reduce the harmful impact of plastic on nature, Kumala aimed to promote the use of the bioplastic11 bag with the aim of defeating conventional plastic. However, one of the major challenges facing Avani was funding and scaling up.

Only time would tell whether Kumala's cassava plastic would be the solution to the giant plastic problem that the world was facing.

Background

In 2014, when taking a sabbatical from his studies in the US, Kumala decided to visit his native Indonesia and enjoy diving and surfing at the country's beaches. One rainy night while he was out enjoying himself with his friends, Kumala noticed passing motorcyclists who were wearing massive plastic raincoats. The sight of the ponchos made them think, "Where do these ugly, toxic rain ponchos end up?" Kevin asserted, "I was with a friend sitting outside a bar and we were seeing hundreds of motorcyclists wearing vinyl ponchos. It clicked that these disgusting, toxic ponchos would be used a few times and then discarded, but they would not decompose."12

The next day, Kumala and his friend headed to one of the landfills and were dumbfounded to see the number of discarded plastic raincoats dumped there. This prompted them to look for a solution, to create a better plastic that would leave no trace one earth. Soon after, Kumala, with a background in biology, medicine, and business management, returned to Indonesia and in 2014, he established Avani with its headquarters in Bali and the main factory on Java Island. The company's name was derived from the definition of the word "Avani" meaning "earth". Its innovations came from the earth, were made for the earth, with the aim to protect and sustain the earth.

Avani produced a full range of sustainable packaging and hospitality products made from renewable and natural ingredients that were fully compostable (Refer Exhibit I for more details on Avani product range). The biodegradable goods went on sale in 2015. The most popular product was the bag made out of cassava with the words "I AM NOT PLASTIC" emblazoned

on it (Refer Exhibit II). The company claimed, "We strive to continuously become a bridge in helping and encouraging communities and businesses to ignite initiative that can generate sustainable impact for the environment. Encouraging the term 'Responsible' as a core driving value of the preceding three key factors: Reduce, Reuse, Recycle."13

Since its inception, Avani had come up with groundbreaking technology that enabled it to replace disposable plastic products which took hundreds of years to decompose by using renewable resources made from plants. In addition, as a social enterprise, Avani was committed to exercising good corporate governance through its business practices as well as by adopting the Triple Bottom Line approach to ensure that its business remained sustainable.

As of December 2017, Avani had progressed to mass scale production, manufacturing up to 200 tons of bio-plastic per month.14 The company had 95 employees and 20 machines. Most of the produce was sold to businesses including shops and hotel groups. While most of these were in Bali and in other parts of Indonesia, there were also a growing number of companies abroad that the company was supplying.

Plastic Epidemic

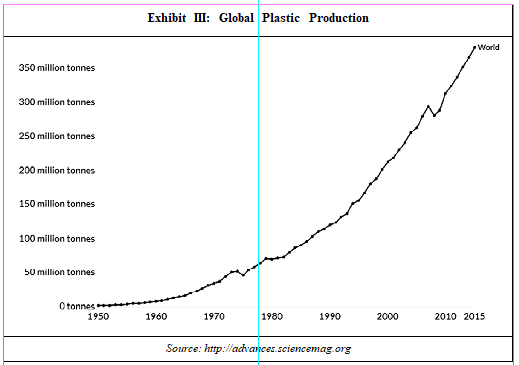

In 1907, the production of Bakelite, the first synthetic plastic, marked the beginning of the global plastics industry. Plastic was a unique material with many benefits. It was cheap, lightweight, and durable. It was, however, non-biodegradable and merely broke down into smaller and smaller pieces with exposure to sunlight. Until the 1950s, however, the rapid growth in global plastic production went unnoticed. Over the years, the annual production of plastics increased nearly 200-fold and reached 381 million tons in 201515 (Refer Exhibit III). This was roughly equivalent to the mass of two-thirds of the world population. Plastic pollution had a huge negative impact on oceans and on the health of wildlife. To make matters worse, plastic waste was grossly mismanaged in many countries, and had become a major source of global ocean plastic pollution. In 2015, an estimated 55% of global plastic waste was discarded, 25% was incinerated, and only 20% recycled.16 By 2016, ocean plastic pollution had emerged as a devastating crisis, and become a matter of concern. According to research by Eunomia Research & Consulting17, more than 80% of the annual input of plastic litter came from land-based sources whereas the remaining 20% came from marine.18

In 2017, according to the report of Ocean Conservancy19 and McKinsey20, 60% of the plastic that entered the world's seas originated from just five countries-China, Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam.21

Indonesia was the second-largest contributor to marine plastic pollution after China.22 The country used 9.8 billion plastic bags per year.23 While more than 80% of the Indonesian Island's economy was dependent on tourism, the plastics strewn over the once pristine beaches posed a threat to tourism. In 2017, Indonesia had to declare a "garbage emergency" after the country's most popular tourist beaches became inundated with a rising tide of plastic waste.24 Record tourist arrivals in Bali, one of those popular tourist destinations, only compounded the problem. In 2017, Bali reportedly recorded more than 5.7 million visitors and that figure was continuously on the rise.25 In 2018, Bali banned single-use plastics including shopping bags, styrofoam, and straws, to curb pollution in its waters and to reduce the pollution by 70% by 2019.26 Wayan Koster, Governor of Bali, said, "This policy is aimed at producers, distributors, suppliers and business actors, including individuals, to suppress the use of single-use plastics. They must substitute plastics with other materials."27 The country also committed itself to developing new industries that used biodegradable materials. It was in this area that Avani was trying to make a difference with its game-changing compostable bioplastic made from cassava starch.

Plastic You Can Drink?

Kumala found the novel solution by converting the edible part of the cassava plant into bags which were non-toxic, sturdy, biodegradable, and compostable in months, certified as non-GMO, and contained no petroleum. Kumala said, "Here in Indonesia we are growing about 25.2 million tons of cassava annually. It means that when it comes to the commodity price, cassava is the most economical commodity available in the country."28 The bags were made from 100% bio-based material and the printing used eco-friendly ink. Moreover, they could be recycled with paper and even added to the compost pile. These bags only needed 90 days to fully decompose, roughly the same time as shredded and soaked cardboard.

The Avani bags felt, looked, and performed like the usual plastic bags, but they were safe for animals. So even if the bags ended up in water bodies or any other place on land, animals remained unharmed even if they consumed it. What was interesting about the bags was that they also dissolved in water. So, they were so safe, that there was no harm done to even people if they swallowed the bag. A video featuring Kumala himself went viral on social media wherein he demonstrated his innovation by dissolving Avani bag in water and drinking the water.29 Kumala said, "I wanted to show this bioplastic would be so harmless to sea animals that a human could drink it. I wasn't nervous because it passed an oral toxicity test."30

Avani also offered a wide range of products, including ponchos, cups, cutlery, and straws made from corn starch, boxes made from bagasse31, and wooden cutlery. The company claimed that all its products were derived from renewable sources and that it promoted a closed-loop circular economy by recovering all materials at the end of a product's life cycle.

Avani's bioplastic products used mostly low value and easy to discard byproducts from the food industry. Kumala said, "I truly believe, if you look 5-10 years down the line. I really believe the utilization of plastic is going to be much, much smaller than what it is today. I think it will go down 70-80% 10 years down the road."32 Kumala's innovation was widely appreciated. The company soon started getting big orders from restaurants and hotels. Around 90% of Avani's 400 clients were expat-owned businesses.

However, the cost of the cassava bags was 50% higher than that of regular plastic bags. But scaling up output, an increase in demand, and better production techniques, were expected to push the costs down. Press TV quoted, "This project has begun at a critical time as reports predict the amounts of plastic in the ocean will surpass fish by 2050. Kumala who's a biology graduate demonstrates how his designed bags do not harm marine or terrestrial life even if burnt before being dissolved into water or earth. Despite its promising features, the non-plastic costs nearly twice the price of plastic as no government funding is aimed at reducing plastic waste. But producers and environmentalists hope that a pay-it-forward-attitude in the market will lower the price of the bio-product."33

Challenges in Turning the Tide

Although Avani was trying to combat plastic pollution, establishing the cassava material as a competitor to traditional plastic was a real challenge. Selling the products to businesses despite the "green premium" that made them more expensive than conventional plastic proved tough. Avani's bags were also subject to criticism for not actually being that eco-friendly in the long run. Experts claimed that not all bioplastics compost easily or completely and some leave toxic residues or plastic fragments behind. The material for the other products Avani Eco sold were sourced in Indonesia, but some items were also made in China as it was more cost effective to do so. That was likely to add to the company's carbon footprint.34

Reportedly, the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) was also skeptical of bioplastics. UNEP stated that "biodegradable" plastics do not breakdown completely and leave a toxic residue.35

Further, most Indonesian-owned businesses were not aware of Avani's existence, as the startup had been focusing more on product development than on marketing.36 Another major challenge that Avani was facing was lack of funds. As bioplastic was more expensive than conventional plastics, there was a possibility that it would limit the sales of the Avani Eco bags. Avani was looking for investors to back the venture. Kumala said, "We want to do this on a bigger scale but it depends who gets on the bus."37

In January 2017, Tuti Hendrawati Mintarsih, Director General for Waste, Toxic and Hazardous Substances Management, Ministry of the Environment and Forestry, Indonesia, conceded that at that point, there was no government funding specifically aimed at reducing plastic waste.38 However, Kumala claimed, "The government is supporting us and we are working with them to create a road map to be plastic-free by 2018. On an island like Bali, it is becoming inevitable that they have to execute right away."39

Analysts opined that with more cities and countries reducing and banning the use of some plastics, the bioplastic industry's biggest challenge could be to meet demand. Some experts also expressed concern over the pressures on land use if crops were grown to feed the bioplastics supply chain.

Road Ahead

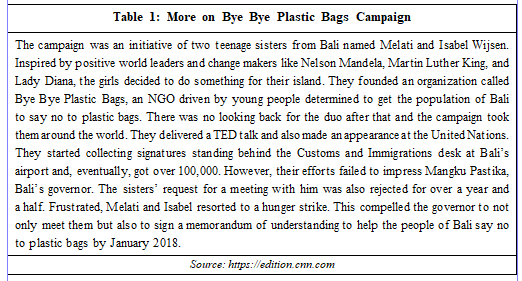

In 2017, Avani benefitted from a campaign called "Bye Bye Plastic Bags" (Refer Table 1). This campaign raised awareness on plastic pollution and forced the government to take action. The government thereafter committed to banning plastic bags by 2018.

The company expected that with more and more media exposure and an increased focus on marketing channels, Avani's products would be widely accepted as a solution to the plastic epidemic, globally. Although Avani was gaining increased international recognition, the company's focus was on increasing its presence in Indonesia. Kumala was also in the process of setting up a downstream company that would deal with the creative distribution of Avani products across Indonesia by raising public awareness via digital content.40

Avani started selling its products in the UAE in 2017. Peter Avram, a partner in Avani Eco Middle East, said "As part of our launch, we will also introduce the full portfolio of Avani eco-friendly products including sugarcane-fiber-based houseware, cornstarch straws, paper and cornstarch coffee cups and wooden cutlery. We have already started to engage with retail, hospitality, hotels and restaurants here to showcase our products and the added value they provide, not only for clients, but also for the end consumer and future sustainability of the UAE."41

Meanwhile, the company was also working with a few non-profit organizations such as Bye Bye Plastic Bags, World Wildlife Fund, and Indonesia Diet Kantong Plastik to raise awareness about the hazards caused by plastic. Reportedly, Avani and the country's Ministry of Environment and Forestry were working closely to create a road map for a cleaner and greener Indonesia. The company was also in the process of tapping into a network of local influencers to spread its message across the nation.

At the same time, critics of bioplastics said that the material did not decay in the landfill or compost pit and needed high temperatures and industrial composting to be considered eco-friendly. They also said that when bioplastics were mixed with other plastic material, they interfered with the recycling of plastic, resulting in recycled products of lower quality. Others pointed out that the Avani products were made from the edible part of food products, which could be used to feed animals, and not the food waste. They pointed out that cassava yields and quality were deteriorating over the years and the species as decaying genetically.

Only time would tell whether cassava would be able to offer a new impetus to biodegradable packaging-and provide concrete solutions to a world battling plastic pollution. And it remained to be seen whether Avani could stop the exacerbating plastic problem with its bioplastic replacements without destroying the planet's precious ecosystems.

Bibliography

- Alex Daniels (2019), "Going Plastic-Free is Easier Than You Think," https://www. debonaironline.com. Accessed on July 1,.2019.

- "The World's Plastic Problem is Bigger Than the Ocean," https://theconversation.com, November 13, 2018.

- Sarah Maisey (2017), "Avani Plant-Based Technology that Rivals Plastic Arrives in the UAE," https://www.thenational.ae, October 8, 2017.

- Dawn Allen (2017), "How Green Are Those New Cassava Bags?," https://www.legalreader. com, August 24, 2017.

- Jacopo Prisco (2017), "The Teenagers Getting Plastic Bags Banned in Bali," https://edition.cnn.com, August 17, 2017.

- "Kevin Kumala Tackles Plastic Waste in Bali," https://www.livingcircular.veolia.com, July 18, 2017.

- Lina PW, "Not Plastic, Kevin Kumala's Social Business," https://view.joomag.com, August 2017.

- Paolo Pirotto, "WWF Report 2019 on Plastic Waste Pollution: Critical Issues and Action Plan," https://www.geoplastglobal.com, May 27, 2019.

- An international non-governmental organization working in the field of wilderness preservation, and reduction of human impact on the environment.

- "Humans are Ingesting 5 Grams of Plastic Per Week," https://www.surfertoday.com, June 21, 2019.

- AzmanUsmani, "World's Plastic Burden: Weight of a Billion African Elephants," https://www.bloomberg quint.com, June 5, 2018.

- Roland Geyer, Jenna R Jambeck and Kara Lavender Law, "Production, Use, and Fate of All Plastics Ever Made," https://advances.sciencemag.org, July 19, 2017.

- Jenna R Jambeck, Roland Geyer, Chris Wilcox, Theodore R Siegler, Miriam Perryman, Anthony Andrady, Ramani Narayan, Kara Lavender Law, "Plastic Waste Inputs from Land into the Ocean," https://science.sciencemag.org, February 13, 2015.

- A tourist destination in Bali.

- Kristi Eaton, "This Plant Makes Boba. A Startup Wants to Use It to Clean Up Plastic," https://www.nbcnews.com, October 4, 2017.

- A cheap and common root vegetable across Indonesia.

- Bioplastics are biodegradable as well as sustainable.

- Kieron Monks, "Plastic You Can Drink: A Solution for Pollution?," https://edition.cnn.com, January 17, 2017.

- Avani Eco, https://www.avanieco.com/about-us/, Accessed on July 8, 2019.

- Priya Raju, "I Am Not a Plastic," https://www.printweek.in, December 8, 2017.

- Hannah Ritchie and Roser Max, "Plastic Pollution," https://ourworldindata.org, September 2018.

- Geyer et al. (2017), op cit.

- UK-based research firm.

- Lorraine Chow, "80% of Ocean Plastic Comes from Land-Based Sources, New Report Finds," https://www.ecowatch.com, June 15, 2016.

- US-based non-profit environmental advocacy group.

- US-based global management consulting firm.

- Jennifer Moller-Gulland, "Vietnam's Tourism and Fishing Industries Drown in Waste," https://www.circleofblue.org, July 19, 2017.

- "Top 20 Countries Ranked by Mass of Mismanaged Plastic Waste," https://www.earthday.org, April 6, 2018.

- Maria Bakkalapulo, "Can Bioplastics Turn the Tide on Indonesia's Waste Problem?," https://www.wbur.org, October 24, 2018.

- "Bali Declares 'Garbage Emergency' Amid Sea of Waste," https://www.thehindu.com, December 28, 2017.

- "Bali to Consider Introducing a 'Tourist Tax' to Tackle Plastic Pollution," https://faroutmagazine.co.uk, January 29, 2019.

- "Indonesia Struggles with Plastic Pollution; Bali Bans Single-Use Plastics," https://www.indonesia-investments.com, December 27, 2018.

- "Bali Bans Single-Use Plastics, Targets 70% Reduction in 2019," https://www.straitstimes.com, December 26, 2018.

- "Bali Takes on Plastic Pollution," https://ecosuck.org, September 1, 2018.

- "Cassava Bioplastic: Dissolvable and Drinkable 'Plastic' Straight Out of Bali," https://coconuts.co, January 18, 2017.

- Muchaneta Kapfunde, "Are Avani's Cassava-Based Eco Bags the Perfect Solution?," https://fashnerd.com, September 10, 2017.

- The dry pulpy residue left after the extraction of juice from sugarcane.

- Bakkalapulo (2018), op. cit.

- Safe Bioplastic Eco Products, https://spinoff.com/avani. Accessed on July 8, 2019.

- "Tackling the Scourge of Plastic with Bags Made of Cassava Starch," https://www.thehindu.com, February 8, 2017.

- Kapfunde (2017), op. cit.

- Alice Jay, "Indonesia's Solution to the Plastic Epidemic," https://indonesiaexpat.biz, February 28, 2017.

- Kieron Monks, "Plastic You Can Drink: A Solution for Pollution?," https://edition.cnn.com, January 17, 2017.

- "Tackling the Scourge of Plastic with Bags Made of Cassava Starch," op. cit.

- Rebecca Coons, "Bali Entrepreneur Launches Cassava-Based Bioplastic," http://biofuelsdigest.com, January 17, 2017.

- Jay (2017), op. cit.

- "Avani Plant-Based Technology that Rivals Plastic Arrives in the UAE," https://www.thenational.ae, October 8, 2017.