Dec'22

The IUP Journal of Entrepreneurship Development

Archives

Motivation of Women Entrepreneurs in Conflict Zones: A case Study of Jammu and Kashmir

Mohammad Furqan Khan

Assistant Faculty, Center for Women Entrepreneurship Kashmir, Jammu and Kashmir Entrepreneurship Development Institute (JKEDI), Srinagar, Kashmir, India; and is the corresponding author. E-mail : furqan.13khan@gmail.com

Roshan Ara

Assistant Professor, Center for Women Studies & Research, University of Kashmir, Srinagar, Kashmir, India. E-mail : Roshanara66@gmail.com

Ziya Aslam

Student, Center for Women Studies & Research, University of Kashmir, Srinagar, Kashmir, India. E-mail: ziyamisgar@gmail.com

Junaid Ahmad Wani

Student, Center for Women Studies & Research, University of Kashmir, Srinagar, Kashmir, India. E-mail: junaidwani571@gmail.com

Heena Gulam

Student, Center for Women Studies & Research, University of Kashmir, Srinagar, Kashmir, India. E-mail: mirhina120@gmail.com

Nadi Azad

Student, Center for Women Studies & Research, University of Kashmir, Srinagar, Kashmir, India. E-mail: nahidajan999@gmail.com

Previous research has overlooked the role of conflict in influencing the factors that motivate women entrepreneurs in troubled economies. This paper aims to explore the in-depth motivations of women entrepreneurs in the conflict zone of Kashmir and simultaneously compare the results with their counterparts in peaceful regions (Jammu Division) of the Union Territory (UT) of Jammu and Kashmir. In other words, this study attempts to extend the context-dependent framework of entrepreneurship to the context of economic disturbance due to conflict. Twenty women entrepreneurs financed by Jammu and Kashmir Entrepreneurship Development Institute (JKEDI), a state funding agency, participated in the study across the UT. In-depth interviews were conducted, and Grounded Theory technique was used to analyze the data. The study's findings show that women in conflict zones are mostly motivated by push factors like family reasons and unemployment. Whereas in peaceful regions, women are driven by entrepreneurial passion and social needs. In contrast, recognition and financial independence were found as significant reasons that inspire women to start business ventures, irrespective of the context. Conflict plays a major role in affecting the motivation of women entrepreneurs across the UT. This study is a unique research contribution, as the motivation of women entrepreneurs in J&K has never been studied in the context of the conflict in the past, particularly with qualitative methods.

Introduction

In recent times, women entrepreneurship has been promoted as a solution to economic and social problems in developing economies (OECD, 2010; and Tuzun and Takay, 2017). The narrative of women entrepreneurship as the savior of underdeveloped nations has become the central theme of development debate across the globe (Valle, 2018). However, despite its importance, women's participation in entrepreneurial activities worldwide varies significantly (Tuzun and Takay, 2017). It has been observed that both formal and informal institutions prevent women from choosing entrepreneurship as a career option (Cullen, 2019).

In the last three decades, there has been a significant increase in women entrepreneurship research globally (Yadav and Unni, 2016; Cardella et al., 2020; and Rashid and Ratten, 2020). Unfortunately, the existing literature on women entrepreneurship has borrowed concepts that were mostly developed on the male-dominated samples (Solesvik et al., 2019). Moreover, research to explore how female entrepreneurship works and what motivates them is also limited to developed nations (Hisrich and Ozturk, 1999; and Rashid and Ratten, 2020). Previous studies show that society and culture affect women entrepreneurs differently across the globe (Rashid and Ratten, 2020). As economic development (Isaga, 2019; and Solesvik et al., 2019) and cultural values (Mordi et al., 2010; and Cullen, 2019) have a significant role in influencing the behavior, it has become essential to distinguish between the factors that motivate women entrepreneurs. Women entrepreneurs share similar characteristics globally, but they significantly differ in their motives for starting and running business ventures (Hisrich and Ozturk, 1999). Many research scholars believe that it is necessary to examine theories based on studies conducted in developed economies before using them in developing markets (Hisrich and Ozturk, 1999; and Isaga, 2019). Similarly, there is a need to re-examine the theories developed in the peaceful and non-violent geographical regions, before they are re-tested in the conflict zones like Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria. Indeed, conflict has terrible economic, social and psychological effects on peoples' lives (Bruck et al., 2013). In the last two decades, violence and conflict have emerged as the most critical challenge for the global community (Aldairany et al., 2018). Even if a country's conflict ends, it leaves the economy with poor infrastructure, widespread corruption, and security issues (Bray, 2009). Regardless of the unfavorable conditions, individuals may develop strong entrepreneurial intentions in severe war zones like Afghanistan. Simultaneously, only a little information is available concerning the factors that drive them towards entrepreneurship (Bullough et al., 2014). Moreover, limited studies have examined country-specific factors that may be a fundamental reason for the difference between factors that affect women's motivation (Cullen, 2019). Every conflict zone has its tale, so the need to explore and understand the target respondents using qualitative methods is vital.

Moreover, only a few studies have been conducted, where qualitative methods were utilized to collect primary data to explore the reasons that motivate women entrepreneurs in conflict zones (e.g., Anosike, 2018; and Althalathini et al., 2020). Previous studies on the subject have mostly relied on secondary data, whereas this research area needs further exploration (Aldairany et al., 2018). Even in the Indian context, only a little has been done to explore the motivation and problems faced by women entrepreneurs in different states of the country (e.g., Agarwal and Lenka, 2016; Pareek and Bagrecha, 2017; and Shastri et al., 2019). Most of the previous studies were conducted in the peaceful Indian states of Rajasthan, New Delhi and Uttar Pradesh. In contrast, not many studies have been conducted in the country's disturbed areas like the North-Eastern states and the UT of Jammu and Kashmir. Particularly Kashmir, which is the most populated region of the UT of Jammu and Kashmir, and has an economy different from the rest of the country because strikes and curfews have been a routine in this part of the world, consequently making life hard for women entrepreneurs than their counterparts in the rest of the country (Nabi et al., 2011; Wafeq et al., 2019; and Althalathini et al., 2020). Therefore, to address this gap in the literature, this study is an attempt to explore the factors that motivate women entrepreneurs in the conflict-hit Union Territory (UT) of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K), India. The purpose of this paper is to explore the in-depth motivations of women entrepreneurs in the UT of J&K and simultaneously compare the results between peaceful (Jammu Division) and conflict areas (Kashmir Division) of the federally governed territory. In other words, this study attempts to extend the context-dependent framework of entrepreneurship to the context of economic disturbance and examine the role of conflict in affecting women entrepreneurs' motivation (Iakovleva et al., 2013). This study is a unique research contribution as the motivation of women entrepreneurs in J&K has never been studied in the context of the conflict in the past, particularly with qualitative methods.

Union Territory of Jammu & Kashmir, India

The partition of British India created three separate nations in South Asia, India and Pakistan in 1947, and later Bangladesh (former East Pakistan) earned its independence from Pakistan in 1971. Partition witnessed communal riots, violence, and a war between the two nations over the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir. The first war they fought ended in 1948, with the princely state's division into two parts between Indian and Pakistan. The first part included three regions known as Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Gilgit and Baltistan controlled by Pakistan. Moreover, the second part included the erstwhile State of Jammu and Kashmir (including Ladakh) came under India's administration. The Line of Control which was agreed to in 1972 divides the territory between India and Pakistan (Kashmir, 2019). India and Pakistan have fought four wars, and the last one was in 1999 at Kargil, Jammu and Kashmir. The conflict between the two countries started to affect the politics and economy of the Kashmir region when the Pakistan-supported insurgency started in Indian controlled Jammu and Kashmir in 1989. Eventually, in the 1990s Muslim-majority Kashmir was turned into the hotbed of militancy and an essential internal security matter for the Indian government (Wikipedia, 2020). Recently, Jammu and Kashmir got a lot of media attention worldwide when on August 5, 2019, India's Parliament passed a bill to divide the erstwhile state of Jammu and Kashmir into UT of Ladakh and UT of J&K. The federal government's action resulted in mixed reactions across the former state of Jammu and Kashmir. In the new UT of Ladakh, there were celebrations in Leh and frustration in Kargil (Dhawan, 2019). Similarly, in the UT of J&K, the Muslim majority region of Kashmir was entirely shut in mourning for months (Jameel, 2020), whereas there were commemorations in Hindu-dominated parts of Jammu division (Bhat, 2020). The newly formed UT of J&K has two divisions, Jammu Division and Kashmir Division. Both have different demographics, culture, climate and topography. The two divisions can be further distinguished based on the political and economic disturbance in the region. Jammu division is more peaceful and has economic activities running throughout the year, whereas Kashmir has seen lockdowns, strikes, and curfews in the last three decades, accompanied by casualties of thousands of civilians, militants, and soldiers.

Jammu Division

Jammu division has been the more progressive region of Jammu and Kashmir's erstwhile state, with premier educational and research institutions like Indian Institute of Management, Indian Institute of Technology and Indian Institute of Mass Communication. With a population of 5,350,811, the Hindu-majority region of the UT is divided into ten administrative districts. Moreover, Jammu is famous for Vaishno Devi shrine, one of the most sacred places of worship for Hindus across the world. Jammu's economy is stable, peaceful and almost similar to the economy of the rest of the country.

Kashmir Division

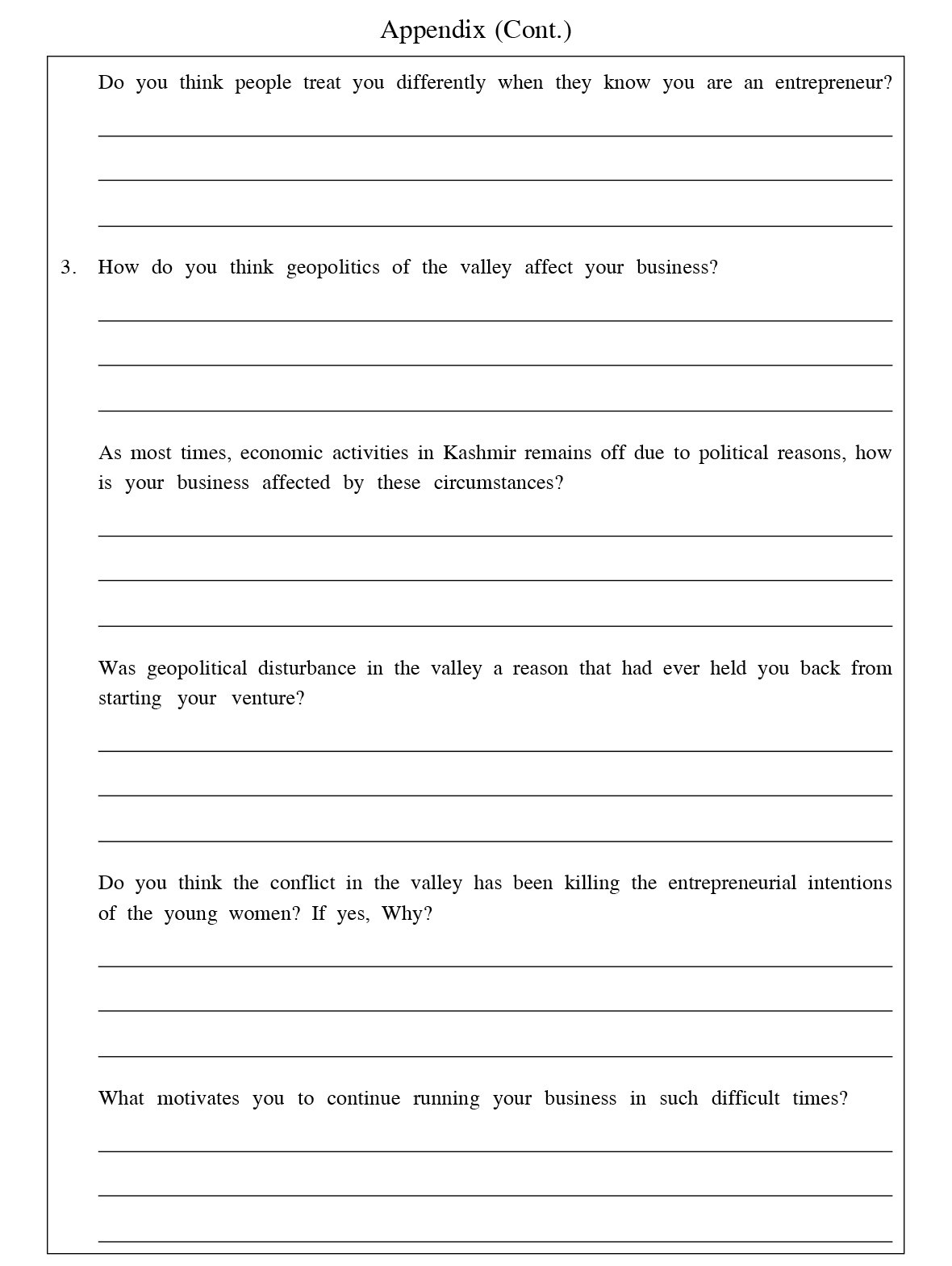

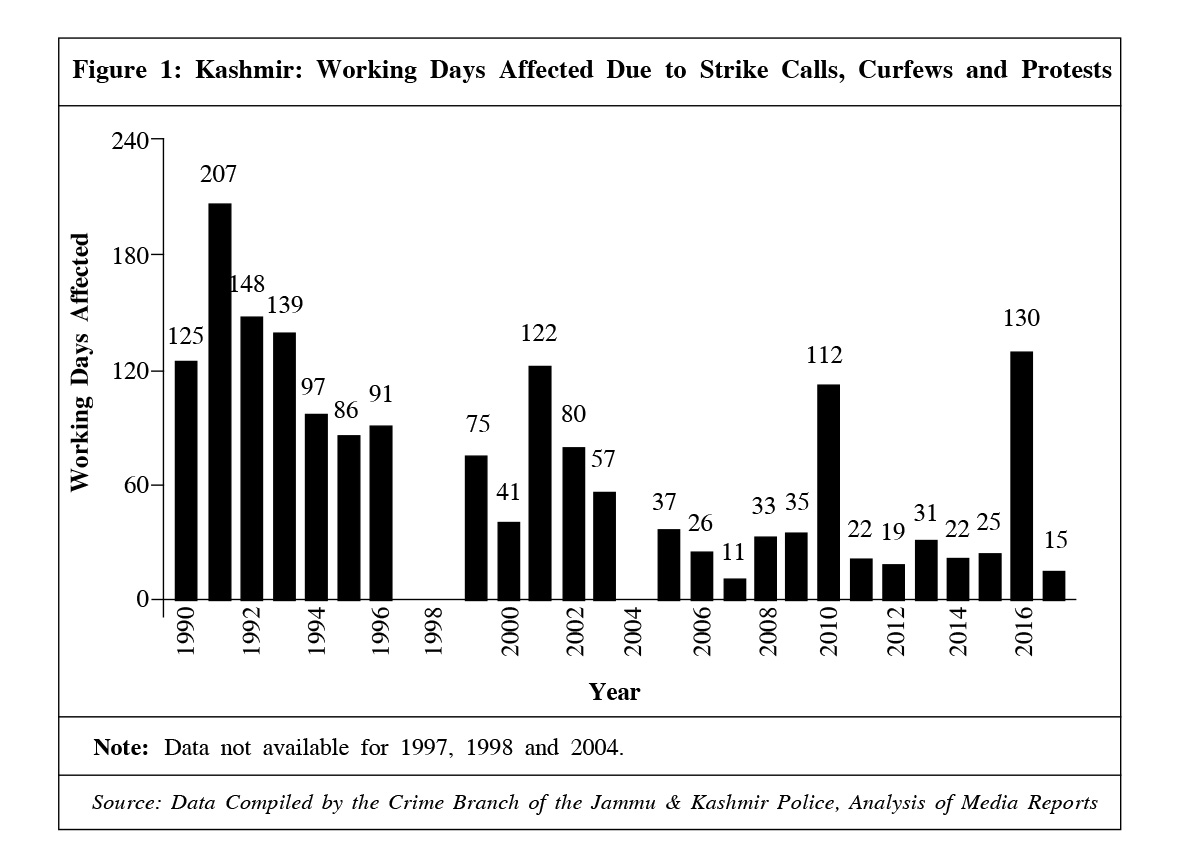

Kashmir is the most populous (6,907,622) and better known region of the UT of J&K. It is well-known for its beautiful snowcapped mountains, breathtaking valleys, and freshwater lakes, but unfortunately, is also the world's most excessively militarized zone (Singh, 2016; and Outlook Bureau, 2018). As per the data released by the Legislative Assembly of Jammu and Kashmir, more than 47,000 people have lost their lives, and 3400 people disappeared since the insurgency started (India, 2008). Many things have changed since then, and the condition is far better than what it was in the 1990s. However, in the last thirty years, violence, protest, strikes, and curfews have eventually become part of Kashmiri culture. With significantly less working days due to strikes and curfews, every passing year makes life challenging for Kashmiri men and women. Particularly after the abrogation of Article 370, Kashmir was shut for months, ruining its economy and creating a financial burden on entrepreneurs and self-employed people. One can understand the difference in life and circumstances in Kashmir by examining the fact that the number of working days in schools never goes beyond 130-140 (Geelani, 2018). To further understand Kashmiri students' and entrepreneurs' condition, we need to examine the statistics from a report compiled by the crime branch of Jammu and Kashmir (as cited by Parvaiz, 2017) (Figure 1).

The data in Figure 1 shows that every year approximately 71 working days were affected by strikes, protests and curfews from 1990 till 2017 (as cited by Parvaiz, 2017). Furthermore, 30 trade bodies of the Valley recently claimed that the Kashmir division had observed 3000 days of lockdown in the last two decades, raising the average to staggering 150 days per year (Bhat, 2020). In Kashmir Valley, businesses have been trying to survive in the most uncertain conditions. Whereas, Jammu division has a business environment similar to the rest of the country.

Literature Review

Motivation of Women Entrepreneurs

Indeed, in the modern world, the motives behind entrepreneurial efforts are the most critical thing to understand as entrepreneurship has become the primary indicator of a nation's development and prosperity (Murnieks et al., 2020). Yadav and Unni (2016) claimed that there is vast scope for building a theoretical base for expanding research on women entrepreneurship. Without any doubt, there is a considerable gender gap in the field of entrepreneurship because of the lack of appropriate training for budding entrepreneurs in countries like India (Vivakaran and Maraimalai, 2017). Researchers have broadly classified motives to start a business into two categories-intrinsic and extrinsic motives (Murnieks et al., 2020). The most dominating reasons to start a business venture in the initial phases of the venture creation are extrinsic or economic (Herbert and Link, 1988; and Murnieks et al., 2020). On the other hand, some studies have shown that the desire for wealth ranks way behind the non-economic reasons like independence and contribution to society (Amit et al., 2001). Previous literature also shows that financial crises and difficult personal circumstances can drive people towards entrepreneurship (George et al., 2016; Miller and Le Breton-Miller, 2017).

On the other hand, intrinsic factors (non-economic factors) like self-realization, innovation, independence, and recognition also play a significant role in attracting people towards entrepreneurship (Edelman et al., 2010). Both intrinsic and extrinsic motives together create an immense desire for starting a business venture among entrepreneurs. To further understand the reasons behind venture creation, it is essential to understand the push and pull factors that affect entrepreneurial intentions (Van der Zwan et al., 2016). Entrepreneurs are either motivated by their necessities (e.g., unemployment, family pressure) or opportunities (e.g., need for achievement, the desire to be independent), that means they are pushed towards entrepreneurship, or sometimes they are pulled towards it (Shapero and Sokol, 1982; Gilad and Levine, 1986; and Van der Zwan et al., 2016). Furthermore, previous research also shows that people are mostly pushed towards entrepreneurship in developing economies, whereas in developed economies, entrepreneurs are driven by opportunities (Van der Zwan et al., 2016). In a study conducted by Solesvik et al. (2019) on women entrepreneurs, it was found that women in developed economies are driven by social motives, whereas in developing economies, profit motives drive them. Context plays a significant role in affecting women's motivation towards entrepreneurship across the globe (Hisrich and Ozturk, 1999). Similarly, there is a need to study what factors affect women's motivation in conflict zones and how they differ from their counterparts in other peaceful regions.

Context of Conflict and Its Impact on Women Entrepreneurs

Scholars have been trying to investigate conflictual environments in various research fields for many years now (Aldairany et al., 2018). A territory is a conflict zone when armed groups systematically use violence to achieve their political ambitions (Bruck et al., 2013). Conflicts have not only terrible socioeconomic ramifications for the affected territories but also the neighboring areas. Wars, civil unrests, and political turmoils create huge uncertainties affecting the lives of people and economies of the nations by making them weak and fragile (Wafeq et al., 2019). Safety issues and corruption practices are prevalent in such economies, consequently creating a challenging business environment for entrepreneurs (Nabi et al., 2011). The impact of violence on economic growth and prosperity is enormous, with an average economic impact of 41% of GDP for the ten most affected countries (Global Peace Index, 2020). In the past few years, extensive rise in conflict worldwide has encouraged the researchers to probe and explore the entrepreneurial culture in conflict economies. In disturbed areas, entrepreneurs have to use different strategies and tactics in dealing with conflict (Muhammad et al., 2016). Indeed, the perception of danger has a negative influence on the entrepreneurial intentions of people living in disturbed territories (Bullough et al., 2014). Troubled economies give a tough time to the business community, particularly female entrepreneurs suffer more in conservative societies (Wafeq et al., 2019). Thus it is crucial to understand what motivates women to start and run business ventures in the context of conflict. Context is essential in understanding how, when, and why entrepreneurship happens (Welter, 2011). However, insignificant information is available about the factors that influence an entrepreneur's decision-making during wars, civil unrest and conflicts (Bullough et al., 2014). It is quintessential to consider the historical, temporal, spatial, institutional, and social contexts in explaining entrepreneurs' behavior (Welter, 2011). Similarly, the context of conflict is also crucial to understand, as entrepreneurs' behavior, because of the state of affairs in a peaceful area, is entirely different from the circumstances in a conflict zone. Economic turmoil due to conflict in countries like Afghanistan have pushed youth towards entrepreneurship (Nabi et al., 2011). While some gender roles were preventing women from contributing to their families, other roles motivated them to start and run their business enterprises to benefit their families (Althalathini et al., 2020). Indeed, context can positively impact entrepreneurship level in an economy, whereas entrepreneurship sometimes can also influence the context (Welter, 2011). A prolonged conflict can badly damage a region's socioeconomics, and on the other hand, it can sometimes empower women entrepreneurs in conservative societies like Gaza (Althalathini et al., 2020).

Moreover, if people become tough and believe in their entrepreneurial capacities, they can develop entrepreneurial intentions in the world's most difficult neighborhoods (Bullough

et al., 2014). Even in the disturbed zone, there are possibilities and desires to explore niche markets, but unfortunately, the business prospects are overshadowed by entrepreneurial problems (Nabi et al., 2011). Previous studies have tried to address the gap in the literature by studying many research problems related to entrepreneurship in the context of conflict, like entrepreneurship education (Anosike, 2018), social entrepreneurship (Sserwanga et al., 2014) and gender roles (Althalathini et al., 2020). However, little work has been done on the motivation of women entrepreneurs in conflict zones. Therefore, it is high time to explore how entrepreneurs behave in disturbed and troubled zones, compared to stable and peaceful environments (Aldairany et al., 2018).

Methodology

This cross-division case study approach in a vast country like India has exploited qualitative methods to explore the hidden motivation of women entrepreneurs in the context of conflict. Solesvik et al. (2019) believed that case study is the most suitable approach for investigations that examine the reasons behind some phenomenon. This study is an effort to understand the circumstances that force women entrepreneurs of different territories of the same country towards entrepreneurship. A case study is the perfect choice for such research problems where we need to get into the respondents' previous and immediate experiences. Furthermore, comparing two different settings provide us with a rich understanding of the phenomenon under investigation and allows for more in-depth probing and examination (Solesvik et al., 2019). The results from a comparative case study cannot be generalized, but such methods are considered appropriate if limited qualitative and quantitative research is available on the subject (Yin, 1994).

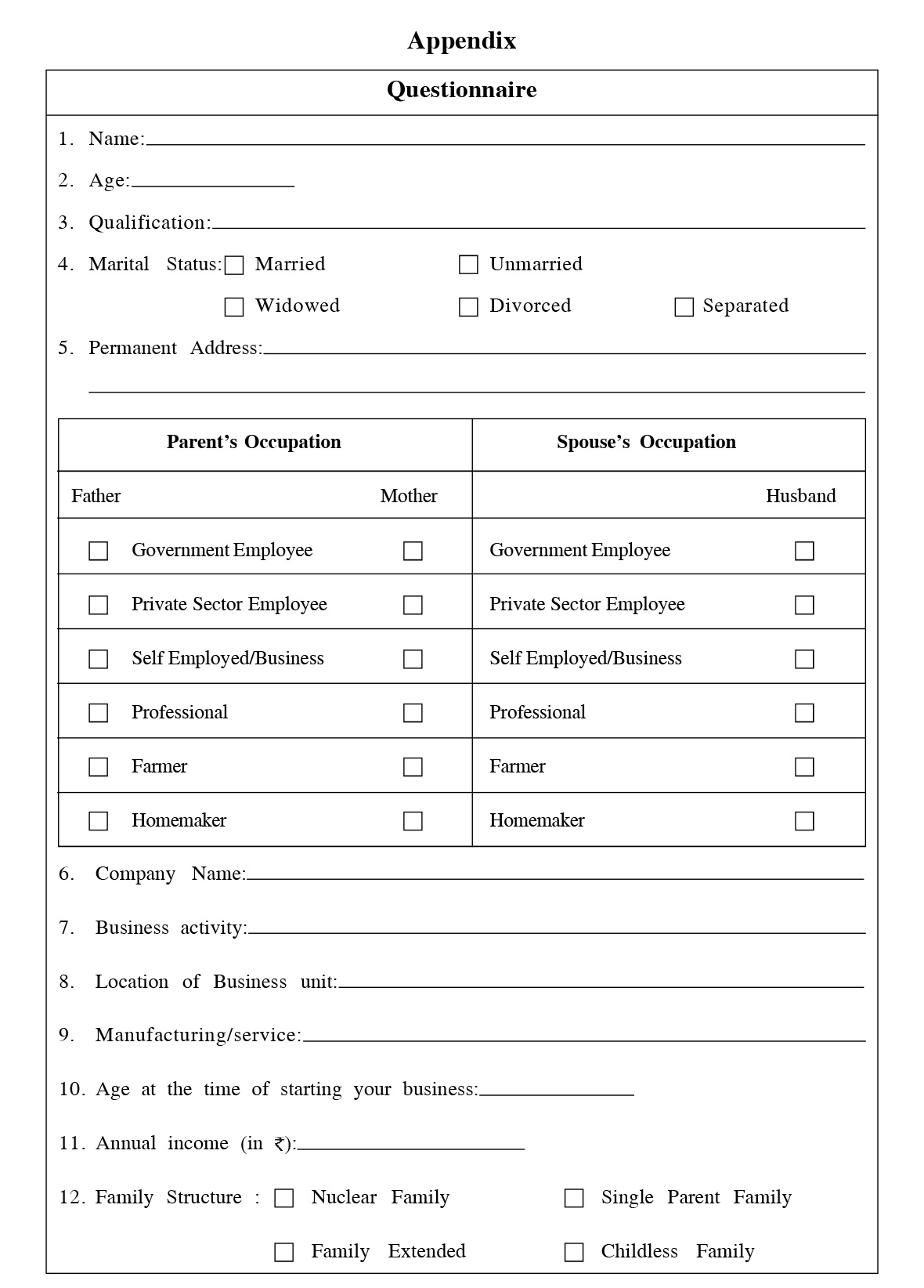

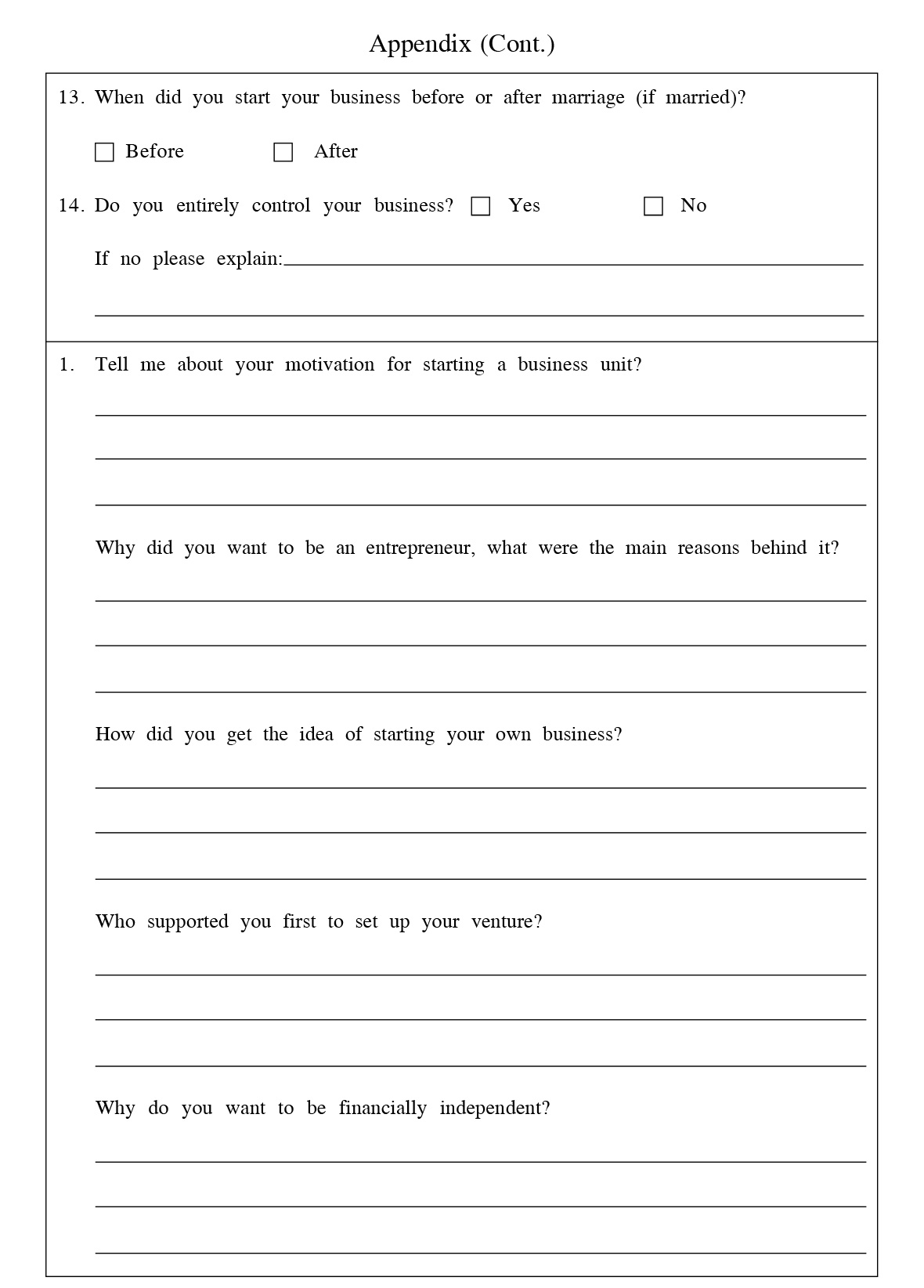

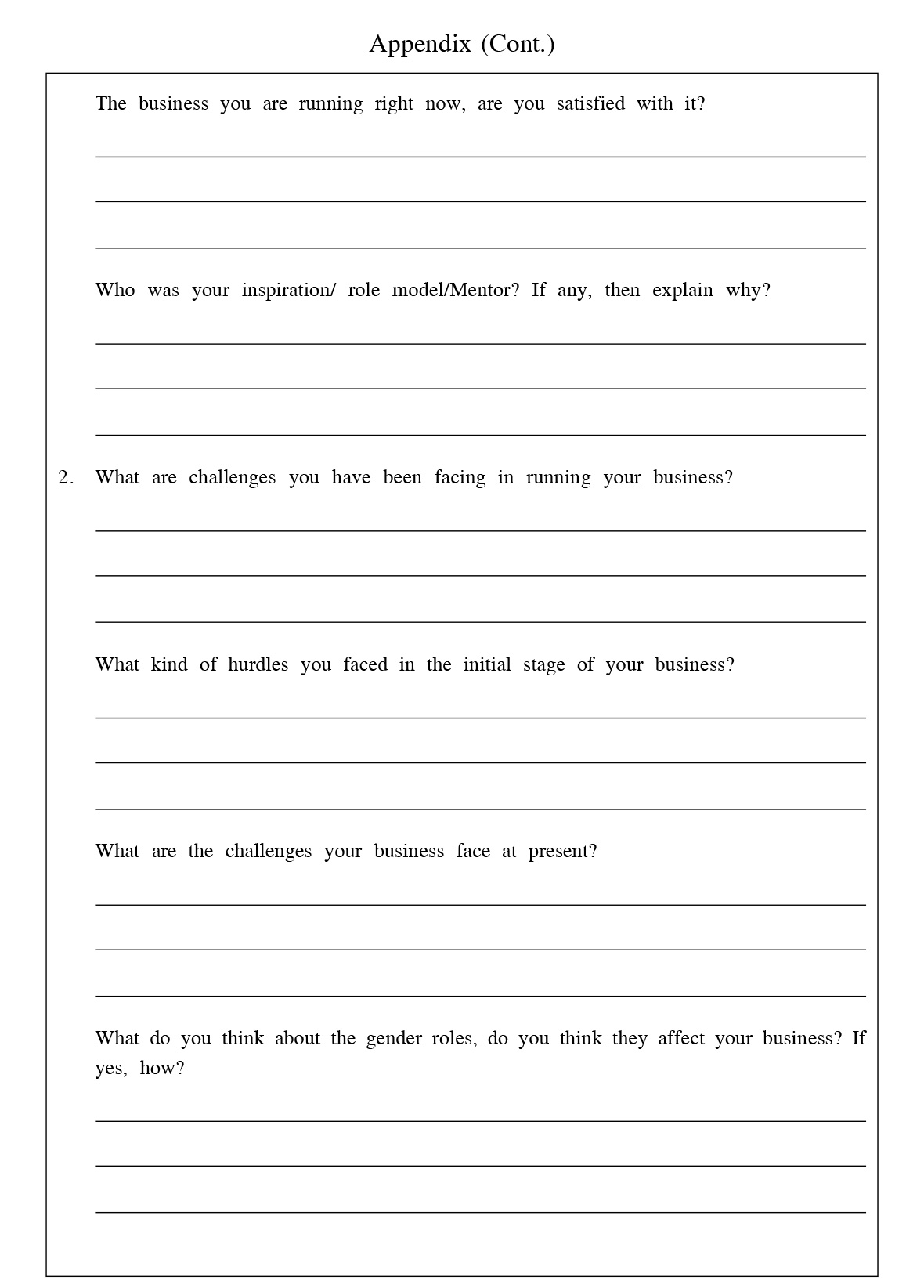

Purposeful sampling was applied to select women entrepreneurs in the UT of Jammu and Kashmir. In this study, Jammu and Kashmir Entrepreneurship Development Institute (JKEDI) staff helped to identify women entrepreneurs who own and control their business. JKEDI is an institution that caters to the training and financial needs of entrepreneurs in UT. As JKEDI has offices across the state in every district of both divisions, they helped us in identifying respondents for data collection. Two qualification criteria were set to identify women entrepreneurs for the interview: (1) The woman entrepreneur must fully own and control her business; and (2) the woman must be running her business for the last three years. Accordingly, to study the motivation of women entrepreneurs in the context of the conflict in Jammu and Kashmir, semi-structured interviews (see Appendix) were used to collect data. Twenty female entrepreneurs financed and sponsored by JKEDI were purposefully selected as respondents for the current study. To make our sample size more representative, we conducted thirteen interviews across Kashmir division and seven across the Jammu division. The Kashmir region is geographically divided into three sub-zones: North Kashmir, Central Kashmir and South Kashmir. Similarly, the Jammu region is divided into three geographical zones: Jammu Plains, Pir Panjal range and Chenab valley. Participation from each zone from both the divisions (of UT of Jammu and Kashmir) was ensured during sample selection. However, data collection from the Pir Panchal Range (Rajouri and Poonch Districts) of Jammu division was not possible due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Interviews were conducted in regional languages in November 2020, were digitally recorded and later translated into English. The main questions were related to the motivation of women entrepreneurs, challenges they face and the support system. Finally, to ensure the data's reliability and validity, the information provided by the candidates was cross-checked with JKEDI and other institutions. Three-stage procedure (initial data coding, theoretical categories, and theory induction) of the Grounded Theory was followed to uncover a novel theory (Corbin and Strauss, 1990), and the data was analyzed following the principles of constant comparison, analytic induction and theoretical sensibility.

Findings

Jammu Division

The Jammu division's business environment is peaceful and is similar to other states of the country. Seven interviews were conducted in Jammu, and efforts were made to get responses from all the different zones like Jammu plains, Pir Panchal range, and Chenab valley. Most of the businesswomen in Jammu division are associated with the services sector, like beauty parlors (2), boutique (1), and general provision stores (1). On the contrary, the region's professionally qualified women also run complicated businesses like hospitals (1) and bakery shops (1). A school dropout from the rural belt of Chenab valley runs a dairy farm (1) for a living. All women entrepreneurs who participated in the study were married, and in 70% cases, occupation of their spouses was business. Our respondent's average age was 34 years because JKEDI does not sponsor candidates aged more than 40 years. All women entrepreneurs who responded to our interview had started their businesses only after their marriage. Which means support from spouses and in-laws in a conservative Indian society has exceptionally increased. Most of the female entrepreneurs in the Jammu division are highly educated and professionally qualified (e.g., MD, MBA), except for a school dropout. The women entrepreneurs of the division are underrepresented in male-dominated professions like construction, but with a few exceptions in healthcare and agro-allied businesses. Women in both developed and developing economies are mostly associated with the services sector (Soleviki et al., 2019).

Motivation

The data collected from the women entrepreneurs of the Jammu division show entrepreneurial passion (5 respondents) as the prime motivating factor for starting a business firm, followed by recognition (4 respondents), financial independence (3 respondents), family reasons (3 respondents) and contribution towards society (1 respondent), except for one respondent, the six others cited multiple motivating factors. In Jammu division, entrepreneurial passion has been acting as a significant motivating factor and women are taking up entrepreneurship as a career choice. A businesswoman who owns a parlor says, "I always wanted to start a parlor before marriage. When I was in 10th standard, I started my business with a small shop and hired some workers. But, unfortunately, I could not retain it because of the skilled-labor needed for the job. Finally, I upgraded my skill and tried my hand in business again after marriage". Similarly, another woman entrepreneur says, "I always wanted to start something of my own; it was my dream to own a business, and I am glad that I chose the right path". Most of the entrepreneurs also said that the financial support provided by the JKEDI (State agency) played a significant role in driving them towards entrepreneurship. Furthermore, financial independence was also a big motivator as Jammu women equate financial independence with dignity, which means women want to prove their worth to society. In some cases, the financial difficulties faced by women also pushed them towards entrepreneurship. For example, a businesswoman explained, "I started my business because of the family's income problems. Also, I wanted to contribute to the financial independence of my family". In contrast to the motivating factors discussed above, a gynecologist who has been running a hospital in an area that had no medical care facilities in the past, stated, "I always wanted to do public service and simultaneously work for financial independence of my family. As we only get to live once, we must use our life for the good of society". In Jammu, women are also socially driven towards entrepreneurship because they want to contribute to their community. It is pertinent to mention that women entrepreneurs' educational and business backgrounds (3 respondents) have also inspired many women towards entrepreneurship.

Challenges

As the study was conducted during Covid-19, problems were faced because of the pandemic- reported by 7 respondents as the significant challenge for Jammu women entrepreneurs. It was followed by market-related barriers (4 respondents), legal and administrative formalities (3 respondents), inadequate management experience (2 respondents), and initial challenges (2). As expected, it was found that geopolitics of the UT of J&K has minimal impact on the business environment of the Jammu division. Low-speed mobile Internet and delivery problems due to the conflict were mentioned by a few respondents as a challenge sometimes.

Kashmir Division

Indeed, life in the Kashmir Valley sometimes can be a nightmare for people from the other parts of the country. Uncertain environment, lockdowns and curfews due to conflict in the region make life inconvenient for the indigenous population. Since the population of Kashmir is 29% more than that of Jammu division, more interviews (13) were conducted in the hinterland. The Kashmir Valley results revealed that 85% of women entrepreneurs are in lifestyle business (11) like boutiques, apparel stores, and embroidery work, with the only exception of a school and a shop providing IT-related services. Approximately 61% of the respondents from the Valley were married, whereas many unmarried entrepreneurs also participated in the study. All married women entrepreneurs had started their business only after their marriage, similar to Jammu division results. Even if Jammu and Kashmir are two different cultures, things have changed positively for women entrepreneurs as spouses' and in-laws' support has increased across divisions. The women entrepreneurs' average age in the valley was 32 years, similar to Jammu respondents' average age (34 years). Most of the women entrepreneurs were college and university passouts (46%), with a significant number of college (23%) and school (30%) dropouts. Women respondents from Kashmir are mostly associated with the services sector, particularly in the lifestyle businesses, with only a few exceptions. Whereas in Jammu Division women have already explored opportunities in manufacturing and agri-allied businesses. A majority of Kashmiri women entrepreneurs come from self-employed/business background (11), whereas less than 50% of women entrepreneurs had a business background in Jammu division. This shows that the change in the attitude towards entrepreneurship is restricted to women coming from a particular socioeconomic background in Kashmir. Simultaneously, there is a massive change in Jammu division because women from service class backgrounds represent more than 50% of women entrepreneurs from the division. The results also show that the percentage of highly educated women in the Valley choosing business as a career choice is less than Jammu division. Professionally qualified women in Jammu are coming forward to bring about social change and are challenging the paradigm.

Motivation

The principal factors that motivated women in Kashmir division towards entrepreneurship are family-related (11) like supporting family members, betterment of children, and financial crises; and sometimes, women are the sole breadwinner of the family. Due to conflict, the heavy loss of life has left thousands of families without any adult male member in the family. A women entrepreneur from the rural area of South Kashmir said, "There was no income from any source and my husband was also unemployed. I was left with no option but to do something to support my family and children." Another woman entrepreneur from North Kashmir shares a similar experience: "There was a time when my father could not afford my studies, he had no regular job, life was hard for us. I always felt bad because I could not help him when I was young. I wanted to help my father and to support my family. The financial crisis in my family was the main reason that motivated me to start something." Many women entrepreneurs also want recognition (10) in family and society, that they are better and can do better things in life. Financial independence (9) and unemployment (5) were also reported as important factors responsible for motivating women towards entrepreneurship. In the Valley, entrepreneurial passion (2) was cited as a reason to start a business by only a few respondents. Whereas, in the Jammu division, it was the main reason that motivated women towards entrepreneurship. In the Valley, the main motive to start a business venture is for sustenance, welfare and prosperity of the family. In the Kashmir Valley, women are mostly pushed towards entrepreneurship and are not taking it up as a career option. Moreover, similar to the Jammu division results, state agency's (9) (JKEDI) role in promoting entrepreneurship in the Kashmir division was favorably reported by the respondents.

Challenges

Conflict in the Kashmir Valley has the maximum impact on economic activities influencing everyday business. As expected, all respondents from the Valley reported the problems arising due to conflict (13) as the biggest challenge women entrepreneurs face regularly. In the initial phases (8) of venture creation, women in Kashmir faced more problems than their Jammu division counterparts, mostly because of the cultural and regional differences. Similar to Jammu division, pandemic-related problems (7) were identified as the significant challenges in doing business. Market-related barriers (4), legal and administrative barriers (2), and inadequate management experience (1) were also reported as challenges faced by female entrepreneurs.

Discussion

This study explored the reasons that drive women towards entrepreneurship and compared the factors that influence their motivation in peaceful and conflict-zone contexts. The paper also explored how conflict affects women entrepreneurs' motivation and their approach towards it. In this discussion, we have examined the factors that motivate women entrepreneurs and compared that to previous literature. Irrespective of the context, we found that women are mostly in lifestyle businesses in both divisions (Jammu and Kashmir). A recent study conducted by Solesvik et al. (2019) compared developing and developed economies and found similar results. However, in peaceful areas of the federal territory, women try difficult and complicated businesses compared to women from conflict zones. Different culture and economic conditions due to the conflict in the Kashmir division could be possible reasons behind that variation (Cullen, 2019; and Isaga, 2019). In this research, we found that women in conflict zones are mostly pushed towards entrepreneurship because of family reasons. The results are similar to previous studies where financial crises and income problems in families had forced women towards entrepreneurship (e.g., Miller and Le Breton-Miller, 2017). Recent studies show that in underdeveloped economies, women are mostly driven by push factors (Isaga, 2019). In challenging economic conditions, women lack intrinsic motivation for running enterprises and are mostly motivated by financial gains and are driven by profit (Althalathini et al., 2020). The socioeconomic conditions in the disturbed economies are responsible for pushing women towards entrepreneurship. The results from this study are similar to the findings of Nabi et al. (2011). Entrepreneurial passion is negligible among women entrepreneurs from disturbed areas, with a few exceptions from professionally qualified women. Difficult economic circumstances and uncertain environment are the reasons that push professionally and highly educated women towards more reliable options (government jobs) of employment instead of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship in conflict economy is not a career option for women but is an alternative for livelihood. Whereas in peaceful Jammu division, women are enthusiastic about entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial passion is the primary motivating factor for venture creation. The findings are in agreement with previous research conducted by Huyghe et al. (2016) and Cardon et al. (2013), where they found entrepreneurial passion as a potent factor responsible for new venture creation. These findings show that female entrepreneurs in peaceful areas are intrinsically motivated towards entrepreneurship and, in other words, are pulled towards it. Shastri et al. (2019) conducted their investigation in the peaceful city of Jaipur in India and found that women are mostly motivated by the pull factors (like independence and creativity). Women in a peaceful business environment are motivated by pull factors like entrepreneurial passion, financial independence, and creativity. In the progressive environment, women choose entrepreneurship as a career option and are not pushed towards it because of family crises or death in a family (George et al., 2016). Recognition emerged as the second major motivating factor in both regions irrespective of the context. As India has a patriarchal culture where women always have pressure to prove their capacity, they crave recognition in the society. Previous research also shows a desire for recognition as a critical factor that affects entrepreneurial behavior (Edelman et al., 2010). Moreover, financial independence was similarly reported by women across divisions as major factors responsible for choosing entrepreneurship. Women in the conflict zone positively reported unemployment as a reason that pushed them towards entrepreneurship, whereas in peaceful areas, family reason was reported as a push factor responsible for entrepreneurship. This result is supported by similar studies conducted on women entrepreneurs in underdeveloped and conflict-hit countries (e.g. Isaga, 2019). In a peaceful environment, women are also driven by social needs and want to contribute to the society they live in, whereas no such reason was reported in the conflict zone of Kashmir. Solesvik et al. (2019) also found similar results while comparing emerging and developed economies.

Problems associated with conflict were reported as significant challenges by women entrepreneurs from Kashmir division. Previous studies conducted in the conflict zones worldwide also show similar results (Althalathini et al., 2020). Whereas market-related barriers, legal and administrative barriers, and inadequate management experience were reported as challenges by female entrepreneurs irrespective of the context. As the study was conducted during the Covid-19 pandemic, problems that emerged because of the government restrictions were also reported as challenges by women entrepreneurs from both divisions.

Conclusion

The UT of J&K's geopolitical conditions have always negatively influenced the socioeconomics of the valley. Ordinary Kashmiri people have been paying the price for living in one of the world's conflict-ridden areas. In the past few decades, women have faced difficult circumstances due to conflict in the region, but fortunately, they have started to come forward and help their families in distress. Sometimes conflict can also empower women, and to fulfil their family responsibilities, they are pushed towards entrepreneurship (Althalathini et al., 2020). Family reasons (like income issues, betterment of children, death in the family, financial crises) are the real factors that force women to take entrepreneurship activities in conflict economies. Entrepreneurship can play a significant role in bringing women on a par with their male counterparts by making them financially independent and giving them the recognition they deserve. The following proposition related to the motivation of the female entrepreneurs in conflict and peaceful economies can be derived:

- In conflict economies, female entrepreneurs are motivated to start a business mainly because of family reasons.

- In peaceful economies, entrepreneurial passion drives women entrepreneurs towards venture creation.

- Women entrepreneurs in both peaceful and conflict economies are motivated by recognition and financial independence.

- In conflict economies unemployment and family reasons push women towards entrepreneurship, whereas in peaceful economies family reasons push women towards entrepreneurship.

- In peaceful economies, social factors also drive women towards entrepreneurship.

Implications: The study attempted to extend the context framework to the "context of conflict" to study women entrepreneurs' motivation for venture creation. This study's findings have initiated a new discussion on women entrepreneurs' motivation in conflict zones and have identified conflict as a moderator in troubled economies. Accordingly, there is a need to differentiate women entrepreneurs based on the context of conflict, particularly in countries or territories facing war/civil war or political instability. This paper's significant theoretical contribution is that it has posited that conflict has a significant effect on the factors that motivate women entrepreneurs.

Currently, potential women entrepreneurs in the Valley are treated similar to their counterparts in the other peaceful regions of the UT and the country at large. The findings of this study make it clear that women from peaceful and conflict zones approach entrepreneurship in different ways. Therefore, the government needs to create different policies based on the state of disturbance in a territory. As the motives for starting business ventures differ in the federal territory, the UT government must give special treatment to Kashmiri women. The government and policymakers need to look at the Kashmiri women entrepreneurs' requirements through the lens of conflict. Consequently, they should work on new schemes that cater to the Valley's women entrepreneurs' needs. There is a need to make structural changes in the way entrepreneurship is promoted in the Valley and how women are trained as part of entrepreneurship development programs. State agencies should not force women towards entrepreneurship but should create an atmosphere where women from the Valley are pulled towards it.

Limitations and Future Scope: This paper attempts to explore the difference in women entrepreneurs' motivation in the context of conflict. Moderately, this study's findings can be generalized to the population of the UT of J&K. Future researchers can use quantitative methods to test the propositions developed during this investigation. Since this study was limited to J&K only, future researchers can extend the geographical scope by simultaneously studying more than one conflict zone and can compare results with the peaceful economies.

References

- Agarwal S and Lenka U (2016), "An Exploratory Study on The Development of Women Entrepreneurs: Indian Cases", Journal of Research in Marketing and Entrepreneurship, Vol. 18, No. 2, pp. 232-247.

- Aldairany S, Omar R and Quoquab F (2018), "Systematic Review: Entrepreneurship in Conflict and Post Conflict", Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, Vol. 10, No. 2, pp. 361-383.

- Althalathini D, Al-Dajani H and Apostolopoulos N (2020), "Navigating Gaza's Conflict Through Women's Entrepreneurship", International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, Vol. 12, No. 4, pp. 297-316.

- Amit R, MacCrimmon K R, Zietsma C and Oesch J M (2001), "Does Money Matter?: Wealth Attainment As The Motive For initiating Growth-oriented Technology Ventures", Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 16, No. 2, pp. 119-143.

- Anosike P (2018), "Entrepreneurship Education Knowledge Transfer in A Conflict Sub-Saharan African Context", Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, Vol. 25, No. 4, pp. 591-608.

- Bhat S (2020), "First Anniversary of Article 370 Abrogation Marked With Grand Celebration in Jammu", India Today, August 5, https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/first-anniversary-of-article-370-abrogation-marked-with-grand-celebration-in-jammu-1708184-2020-08-05

- Bhat W (2020), "Kashmir Witnessed 3000 Days of Lockdown in Over Two Decades: Trade Bodies", Ground Report, June 4, https://groundreport.in/kashmir-3000-days-of-lockdown/

- Bray J (2009), "The Role of Private Sector Actors in Post-conflict Recovery: Analysis", Conflict, Security & Development, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 1-26.

- Bruck T, Naude W and Verwimp P (2013), "Business Under Fire: Entrepreneurship and Violent Conflict in Developing Countries", Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol. 57, No. 1, pp. 3-19.

- Bullough A, Renko M and Myatt T (2014), "Danger Zone Entrepreneurs: The Importance of Resilience and Self-Efficacy for Entrepreneurial Intentions", Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Vol. 38, No. 3, pp. 473-499.

- Cardella G M, Hernandez-Sanchez B R and Sanchez-Garcia J C (2020), "Women Entrepreneurship: A Systematic Review to Outline the Boundaries of Scientific Literature", Frontiers in Psychology, Vol. 11, p. 1557.

- Cardon M S, Gregoire D A, Stevens C E and Patel P C (2013), "Measuring Entrepreneurial Passion: Conceptual Foundations and Scale Validation", Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 28, No. 3, pp. 373-396.

- Corbin J M and Strauss A (1990), "Grounded Theory Research: Procedures, Canons, and Evaluative Criteria", Qualitative Sociology, Vol. 13, No. 1, pp. 3-21.

- Cullen U (2019), "Sociocultural Factors as Determinants of Female Entrepreneurs' Business Strategies", Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, Vol. 12, No. 1, pp. 144-167.

- Dhawan H (2019), "Celebrations in Leh, Disappointment in Kargil - Mixed Reactions in Ladakh to Union Territory Status", Times of India, August 22. Retrieved from http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/articleshow/70722319.cms?utm_source= contentofinterest&utm_medium=text&utm_campaign=cppst_prime

- Edelman L F, Brush C G, Manolova T S and Greene P G (2010), "Startup Motivations and Growth intentions of Minority Nascent Entrepreneurs", Journal of Small Business Management, Vol. 48, No. 2, pp. 174-196.

- Geelani R (2018), "Amid Frequent Closures, Mhrd Asks Jk to increase Working Days in Schools", Greater Kashmir, April 14. Retrieved from https://www.greaterkashmir. com/news/kashmir/amid-frequent-closures-mhrd-asks-jk-to-increase-working-days-in-schools/

- George G, Kotha R, Parikh P et al. (2016), "Social Structure, Reasonable Gain, and Entrepreneurship in Africa", Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 37, No. 6, pp. 1118-1131.

- Gilad B and Levine P (1986), "A Behavioral Model of Entrepreneurial Supply", Journal of Small Business Management, Vol. 24, No. 4, pp. 45-53.

- Global Peace Index (GPI) (2020), "Global Peace Index 2020", https://visionof.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/GPI_2020_web.pdf

- Hebert R F and Link A N (1988), The Entrepreneur: Mainstream Views & Radical Critiques, Praeger Publishers.

- Hisrich R D and Ozturk S A (1999), "Women Entrepreneurs in a Developing Economy", Journal of Management Development, Vol. 18, No. 2, pp. 114-125.

- Huyghe A, Knockaert M and Obschonka M (2016), "Unraveling the "Passion Orchestra" in Academia", Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 31, No. 3, pp. 344-364.

- Iakovleva T, Solesvik M and Trifilova A (2013), "Financial Availability and Government Support For Women Entrepreneurs in Transitional Economies: Cases of Russia and Ukraine", Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, Vol. 20, No. 2, pp. 314-340.

- India R (2008), "India Revises Kashmir Death Toll to 47,000", Thomson Reuters Corporate, p. 6.

- Isaga N (2019), "Start-up Motives and Challenges Facing Female Entrepreneurs in Tanzania", International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship.

- Jameel Yousuf (2020), "Mutilation of J&K: A year of unwinning Kashmir", Deccan Chronicle, July 29. Retrieved from https://www.deccanchronicle.com/opinion/op-ed/290720/mutilation-of-jammu-and-kashmir-a-year-of-unwinning-kashmir.html

- Kashmir (2019), Encyclopedia Britannica, October 31, https://www.britannica.com/place/Kashmir-region-indian-subcontinent

- Miller D and Le Breton-Miller I (2017), "Underdog Entrepreneurs: A Model of Challenge Based Entrepreneurship", Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, Vol. 41, No. 1, pp. 7-17.

- Mordi C, Simpson R, Singh S and Okafor C (2010), "The Role of Cultural Values in Understanding The Challenges Faced By Female Entrepreneurs in Nigeria", Gender in Management: An International Journal, Vol. 25, No. 1, pp. 5-21.

- Muhammad N, Ullah F and Warren L (2016), "An institutional Perspective on Entrepreneurship in A Conflict Environment", international Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, Vol. 22, No. 5, pp. 698-717.

- Murnieks C Y, Klotz A C and Shepherd D A (2020), "Entrepreneurial Motivation: A Review of The Literature and An Agenda For Future Research", Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 41, No. 2, pp. 115-143.

- Nabi G, Linan F, Muhammad A, Akbar S and Dalziel M (2011), "The Journey To Develop Educated Entrepreneurs: Prospects and Problems of Afghan Businessmen", Education + Training, Vol. 53, No. 5, pp. 433-447.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2010), "Education at a Glance 2010: OECD Indicators", OECD, Paris.

- Outlook Bureau (2018), "Children in J&K Living in the most Militralised Zone of the World, 318 Killed in Last 15 years, Say Human Rights Group Report", Outlook The Fully Loaded Magazine, March 30, https://www.outlookindia.com/website/story/children-in-jk-living-in-most-militarised-zone-of-the-world-318-killed-in-15-year/310230

- Pareek P and Bagrecha C (2017), "A Thematic Analysis of the Challenges and Work-Life Balance of Women Entrepreneurs Working in Small-Scale Industries", Vision, Vol. 21, No. 4, pp. 461-472.

- Parvaiz Athar (2017), "Since July 2016, Kashmir Schools & Colleges Have Been Shut on 60% of Working Days", Indiaspend, May 30, https://archive.indiaspend.com/cover-story/since-july-2016-kashmir-schools-colleges-have-been-shut-on-60-of-working-days-22058

- Rashid S and Ratten V (2020), "A Systematic Literature Review on Women Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies While Reflecting Specifically on SAARC Countries", Entrepreneurship and Organizational Change, pp. 37-88, Springer, Cham.

- Shapero A and Sokol L (1982), "The Social Dimensions of Entrepreneurship", In Encyclopedia of Entrepreneurship, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, pp. 72-90.

- Shastri S, Shastri S and Pareek A (2019), "Motivations and Challenges of Women Entrepreneurs: Experiences of Small Businesses in Jaipur City of Rajasthan", International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, Vol. 39, Nos. 5/6, pp. 338-355.

- Singh Rani (2016), "Kashmir: The World's Most Militarized Zone, Violence after Years of Comparative Calm", Forbes, July 12, https://www.forbes.com/sites/ranisingh/2016/07/12/kashmir-in-the-worlds-most-militarized-zone-violence-after-years-of-comparative-calm/

- Solesvik M, Iakovleva T and Trifilova A (2019), "Motivation of Female Entrepreneurs: A Cross-national Study", Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, Vol. 26, No. 5, pp. 684-705.

- Sserwanga A, Kiconco R I, Nystrand M and Mindra R (2014), "Social Entrepreneurship and Post Conflict Recovery in Uganda", Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, Vol. 8, No. 4, pp. 300-317.

- Tuzun I K and Takay B A (2017), "Patterns of Female Entrepreneurial Activities in Turkey", Gender in Management: An International Journal, Vol. 32, No. 3, pp. 166-182.

- Valle F S (2018), "Moving Beyond Co-Optation: Gender, Development, and Intimacy", Sociology of Development, Vol. 4, No. 4, pp. 325-345.

- van der Zwan P, Thurik R, Verheul I and Hessels J (2016), "Factors influencing The Entrepreneurial Engagement of Opportunity and Necessity Entrepreneurs", Eurasian Business Review, Vol. 6, No. 3, pp. 273-295.

- Vivakaran M V and Maraimalai N (2017), "Feminist Pedagogy and Social Media: A Study on Their integration and Effectiveness in Training Budding Women Entrepreneurs", Gender and Education, Vol. 29, No. 7, pp. 869-889.

- Wafeq M, Al Serhan O, Gleason K C et al. (2019), "Marketing Management and Optimism of Afghan Female Entrepreneurs", Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, Vol. 11, No. 3, pp. 436-463.

- Welter F (2011), "Contextualizing Entrepreneurship-Conceptual Challenges and Ways Forward", Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Vol. 35, No. 1, pp. 165-184.

- Wikimedia Foundation (2023), "Insurgency in Jammu and Kashmir", Wikipedia, Retrieved February 14, 2023, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Insurgency_in_ Jammu_and_Kashmir

- Yadav V and Unni J (2016), "Women Entrepreneurship: Research Review and Future Directions", Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, Vol. 6, No. 1, pp. 12.

- Yin R K (1994), "Discovering the Future of the Case Study Method in Evaluation Research", Evaluation Practice, Vol. 15, No. 3, pp. 283-290.