Sep'18

The IUP Journal of Entrepreneurship Development

Archives

SHG Women Microentrepreneurs' Attributes and Gender Issues: A Study

Cidda Reddy Jyoshna

Assistant Professor,

Department of MBA,

Sreenivasa Institute of Technology and Management Studies,

Chittoor, Andhra Pradesh, India;

and is the corresponding author.

E-mail: josh.jyoshna2008@gmail.com

Cheekoori Jyothsna

Assistant Professor,

Sreenivasa Institute of Technology and Management Studies,

Chittoor Andhra Pradesh, India.

E-mail: jyothsnacheekoori@yahoo.com

B Ujwala

Assistant Professor,

Sri Vidhyanikethan Institute of Management,

Tirupathi Andhra Pradesh, India.

E-mail: drbujwala@gmail.com

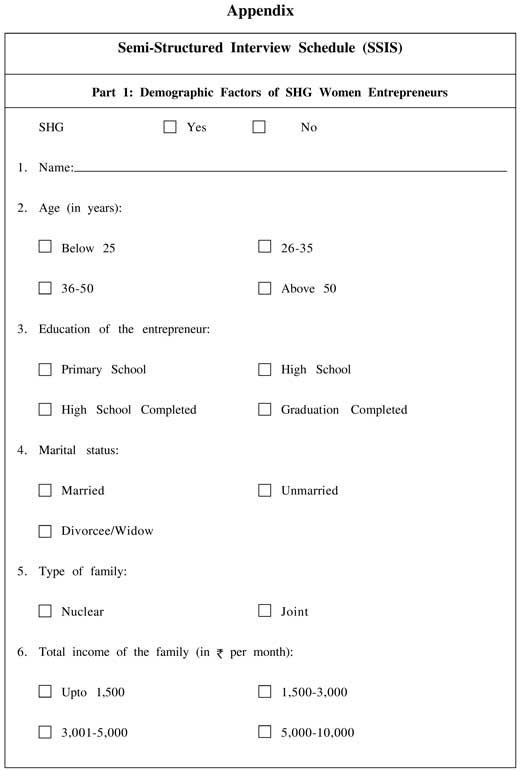

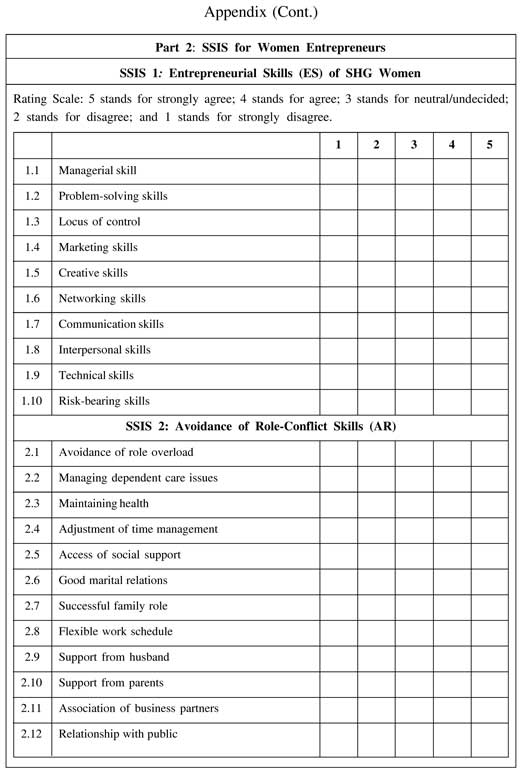

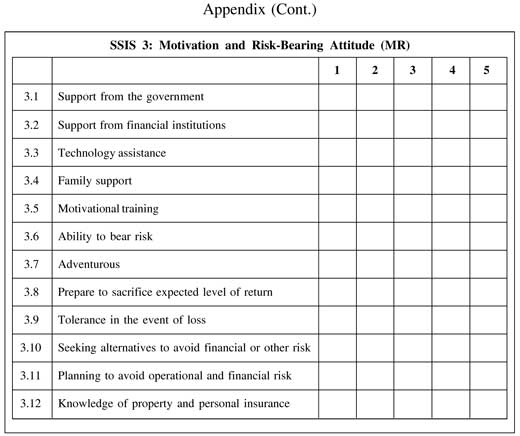

The purpose of the study is to examine the relationship between Self-Help Group (SHG) women microentrepreneurs' attributes and gender issues in achieving women entrepreneurship development. The target sample for the study was 600 SHG women entrepreneurs operating in Chittoor district of Andhra Pradesh, India. Simple random sampling method was adopted to survey the scattered population all over the district. The researcher used Semi-Structured Interview Schedule (SSIS) as survey tool. Statistical tools, including reliability and validity test, chi-square test and correlation test, were used for data analysis.

Introduction

Women entrepreneur is a person who accepts a challenging role to meet her personal needs and become economically independent. A strong desire to do something positive is an inbuilt quality of an entrepreneurial woman, who is capable of providing values to both family and society (Singh, 2012).

Self-Help Groups (SHGs) are small economical homogenous affinity groups of rural poor, willingly formed to save and mutually contribute a common fund to be lent to its members as per group decision (NABARD, 1997). Singh and Jain (1995) defined SHGs as voluntary association of people formed to attain both social and economic goals. They are also known as Rotating Savings and Credit Associations (ROSAs), chit funds and revolving funds (Malcolm, 1998; and Ojha, 2001).

In the present study, all the SHGs consist of only women members. More than 40% of the SHGs that exist in India are in Andhra Pradesh and about 20% of all the women SHGs that exist in the world belong to Andhra Pradesh (Kurien, 2003).

The project was started in 1976, and it was formally recognized as a bank through an ordinance, issued by the government in 1983. The Grameen Bank provided credit loans particularly to needy women in order to promote self-employment. Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC) and Association for Social Advancement (ASA) are principal Microcredit Finance Institutions (MFIs) operating for over two decades and their activities are spread all over the country. BRAC is the largest NGO of Bangladesh having a total membership of 41.38 lakh which was started in 1972 as a relief organization (Bouman, 1995).

India has been following Bangladesh's model in a tailored form. To eliminate poverty and empower women, microfinance was started as a powerful instrument in the novel economy. SHGs and credit management groups were started in India to ensure easy availability of microcredit, and thus the movement of SHG spread in India (Karmakar, 2003). In India, banks are the predominant agency for delivery of microcredit. During 1970, Ilaben Bhat started Self-Employed Women's Association (SEWA) in Ahmedabad and developed a concept of 'women and microfinance'. It was later followed by the Annapurna Mahila Mandal in Maharashtra and Working Women's Forum in Tamil Nadu. Further, National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD) sponsored many groups on the lines of those developed by SEWA. SEWA is a trade union of poor and self-employed women workers (Singh, 2007).

In India, women entrepreneurship is a recent development, which started only after the 1970s with the introduction of the Women's Decade (1975-1985) and which mostly picked up in the late 1970s. The participation of women in economic life in developing countries contributed to a more humane, cooperative, balanced and pleasant work environment in women-led enterprises, in which individual development is also involved. Many of the traditional occupations open to women are mainly based on caste and creed and the nature of self-employment is based on the standard of living. At present, women are generating employment for themselves in unorganized sectors and other category of women are also providing employment for others.

Women in India have been oppressed culturally, socially, economically and politically for centuries. Women entrepreneurship development is an emerging concept with the support of progressive social, legal, cultural, economic, political and technological advancement (Goyal and Jai, 2012). The ultimate objective of the formation of the SHGs is to empower the needy rural women and to train them for income-generation programs so as to reduce poverty and increase the standard of living in the rural areas.

Poor understanding of government policies, poor technical know-how, financial and resource constraints during start-up period, inability to face competition and lack of quality control are some of the major constraints that put the women microentrepreneurs into jeopardy. The gender gap is also one of the potential reasons which prohibit development of women entrepreneurs. Against this backdrop, the present study aims to examine the relationship between SHG women microentrepreneurs' attributes and gender issues and entrepreneurship development.

Literature Review

Entrepreneurial Skills

Meredith et al. (1982) and Chandler and Jansen (1992) opined that entrepreneurial skills like self-confidence, risk-taking ability like Knight's entrepreneur, flexibility, and need for achievement like McClelland's entrepreneur are positively related to the victory of his/her business. Hisrich and Brush (1984) showed that managerial skills, idea generating skills and interpersonal skills are important for women entrepreneurs in starting a business. According to Mc Elwee (2008), networking, innovation, risk taking, team working, reflection, leadership, locus of control and business monitoring are the fundamental skills required for an entrepreneur.

Avoidance of Role-Conflict Skills

Since women joined business and entered into higher positions of influence, they have been wearing multiple hats at the same time. This multi-tasking trait is one that some may argue women have mastered in order to manage all the responsibilities of the family as well as work (Ruderman et al., 2002). Work-life balance issues sometimes can result in positive outcomes, like growth of entrepreneurial ventures pursued by women that give them flexible schedules (Rehman and Muhammad, 2012). Jean and Choo (2001) commented that family members' and others' support can reduce the role-conflict of women entrepreneurs.

Motivation and Risk-Bearing Attitude

There is a strong theme of family and personal survival and security that in all likelihood reflects a push factor from the macro-economic context of rural decline (Newton et al., 2003). Dann (2000) revealed that the reasons for establishing small business differ in so far as they represent a greater proportion of general business needs as well as personal internal needs. Srivastava and Chaudhary (1991) in their work on women entrepreneur's problems, perspective and role expectations of the banks identified no single factor but a host of motivating factors that act simultaneously on the individuals, creating dissonance in them.

Gender Equality

According to Dhameja (2002), women entrepreneurs have long felt that they have been discriminated against by various social and cultural factors. This argument is supported by Otero (1999) and Rajendran (2003) that women entrepreneurs are subjected to gender-related discrimination, especially in developing countries in the area of distribution of social wealth such as education and health.

From the review of related literature, the problems faced by women entrepreneurs are identified as:

- Shortage of skills, knowledge and experience to intervene in entrepreneurial activity;

- Lack of motivation and poor competency level; and

- Problem of dual role, i.e., family and profession.

Keeping in view the above research problems, the research questions that arise are:

- What are the demographic and professional characteristics that affect the SHG women microentrepreneurship development?

- What are the key entrepreneurial attributes that affect the success of SHG women microentrepreneurs?

- Do gender issues affect the success of SHG women microentrepreneurs?

Objective

After analyzing the research problem and research questions, the present study aims to:

- Explore and identify SHG women microentrepreneurs' demographic characteristics that affect women entrepreneurship development;

- Analyze and examine microentrepreneurs' attributes (namely, entrepreneurial skills, avoidance of role-conflict and motivation and risk bearing attitude) that affect SHG women microentrepreneurs' success; and

- Explore and identify the gender issues that affect SHG women microentrepreneurs' success.

Based on the objectives, the following hypotheses are developed for testing:

H01: There is no significant relationship between entrepreneurial skills and avoidance of role-conflict skills of SHG women.

Ha1: There is significant relationship, i.e., the higher the avoidance of role-conflict skills, the higher the entrepreneurial skills of SHG women.

H02: There is no significant relationship between entrepreneurial skills and motivation-cum-risk-bearing attitude.

Ha2: There is significant relationship, i.e., the higher the motivation-cum-risk-bearing attitude, the higher the entrepreneurial skills.

H03: There is no significant relationship between entrepreneurial skills and gender issues.

Ha3: There is significant relationship between entrepreneurial skills and gender issues.

Data and Methodology

This research was conducted from the perspectives of SHG women entrepreneurs in Chittoor district in the State of Andhra Pradesh, India. The DWCRA Movement was started in the Chittoor district in the year 1992. Later under SGSY, it was converted to SHG movement. The project APRPRP started functioning in the district with effect from June 2002. The old groups and newly formed groups are strengthened through the continuous facilitation support given by Indira Kranthi Patham (IKP) staff such as community coordinators and assistant project managers along with social capital formed at the village level.

District Project Management Units (DPMUs) have taken the initiative for federation of SHGs into Village Organizations (VOs) and VOs into Mandal Samakhyas which also helped in strengthening institution building of Community-Based Organizations (CBOs). All Mandal Samakhyas were federated to Zilla Samakhyas which is the apex body of CBOs in the Chittoor district. The SHGs' performance is continuously monitored and evaluated by DPMU and their federations (IKP, 2008).

The study pertains to microenterprise level. Hence, it is very important to examine the demographic, professional and motivational characteristics of the SHG women. There were 52,095 SHG women microentrepreneurs operating in the Chittoor district (District Collectorate, 2014). 1000 women microentrepreneurs were approached for the study randomly. Out of the respondents interviewed, 656 gave their responses. Based on the quality and relevancy of the response, the researcher finalized 600 samples with a favorable response rate of 91%.

Sample survey and delphi method were used in the study. Both primary and secondary data were collected for the study. A district-wise survey in the Chittoor district of Andhra Pradesh was administered for the study. A Semi-Structured Interview Schedule (SSIS) was designed as a tool for the sample survey (see Appendix). The researcher prepared the schedule in dual language (Telugu and English) which made it more convenient in probing the fact from rural and semi-urban SHG women entrepreneurs. Statistical tools, including reliability, validity, chi-square test and correlation, were used for data analysis.

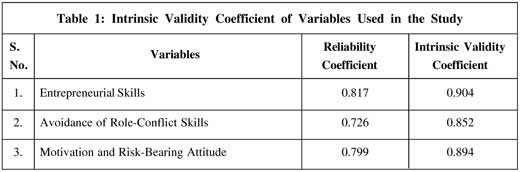

Table 1 shows that all the calculated values of coefficients of entrepreneurial attributes of SHG women are highly valid. The reliability of the variables was highly consistent with coefficients above 0.60. Hence, it is concluded that the questionnaire construct pertaining to the SHG women entrepreneurial study variables is valid.

Results and Discussion

Research Question 1: What are the demographic and other professional characteristics that affect SHG women entrepreneurship development?

With the help of the review of literature, the researcher developed demographic factors (age, education, marital status and family type), professional factors (such as family income) and motivational factors which influence the SHG women entrepreneurship development.

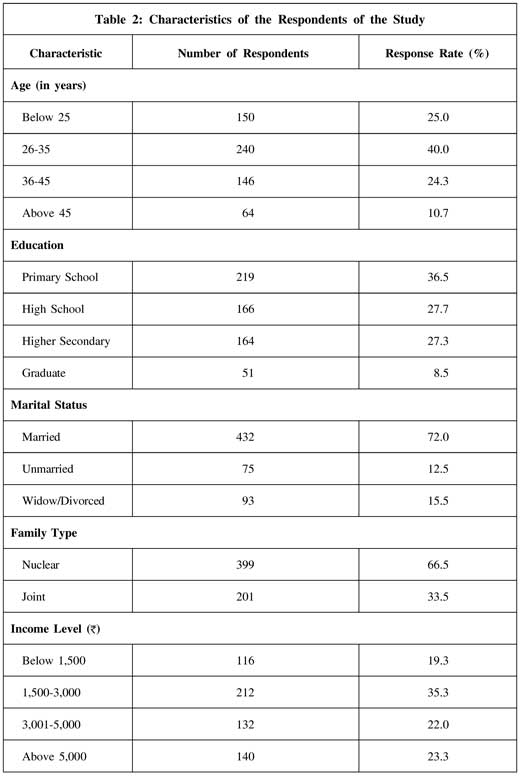

Age: This study found that there was significant difference between age groups of SHG women entrepreneurs and age factor has a positive effect on SHG women entrepreneurship development factors. It is observed from Table 2 that out of total 600 respondents, a majority of the respondents were in the age group of 26-35 years with 240 responses as compared to the age group below 25 years (150 responses) and age group of 36-45 years (146 responses). The age group above 45 years had least (64) respondents. Thus, it is inferred that the SHG women in the age group of 26-35 years have greater affinity towards entrepreneurial participation. This study also explored the strong empirical evidence of entrepreneurship through SHG women in the region.

Education: It is an important criterion for deciding the entrepreneurial activity of SHG women. It is observed from Table 2 that the respondents with primary school education were highest (219) in comparison to those with high school education (166) and Higher Secondary education (164). The respondents who were graduates were least (51) in number. From the findings, it is inferred that the SHG women with primary education show greater affinity towards entrepreneurial participation. This is consistent with the finding of Bruni et al. (2004) who suggested that the option of creating a business is left basically to those people who did not have a high educational level.

Marital Status: It is observed from Table 1 that married respondents were highest (432), followed by widow/divorced (93), and unmarried respondents (75). Therefore, married SHG women show greater interest towards entrepreneurial participation. The study result revealed that marital status has a positive effect on SHG women entrepreneurship development factors. Many studies (Aldrich and Cliff, 2003) have proved that although women entrepreneurs work full-time outside the home, the responsibility of carrying out the daily chores at home still falls on them, thus discouraging women entrepreneurship.

Family Type: In this study, an important relationship was established between women entrepreneurship and family type. Table 2 reveals that a majority of the respondents had nuclear family (399). From the above findings, it is inferred that SHG women having nuclear family show greater affinity towards entrepreneurial participation. It is empirically proved that family type has a positive effect on SHG women entrepreneurship development factors, except avoidance of role-conflict skills. The result is consistent with that of Lee and Choo (2001) who commented that family members' and others' support can reduce the conflict of women entrepreneurs.

Income Level: The existing income level difference of the SHG women has a positive effect on entrepreneurship development. It is observed that respondents belonging to the family income group of 1,500-3,000 is highest (212), followed by respondents belonging to the family income group of above 5,000 (140), between 3,001-5,000 (132) and below 1,500 (116). From the above findings, it is inferred that the SHG women having family income 1,500-3,000 have greater affinity towards entrepreneurial participation. It is observed that a majority of SHG women entrepreneurs have weak financial background, i.e., most of them had an earning of below 5,000 per month during their entry into the entrepreneurial activity. Thus, there are evidences that family income has a positive effect on women entrepreneurship development. This is also consistent with the findings of Aldrich and Cliff (2003) who explored that if the work conditions and income level are low, then women enter into new business, i.e., entrepreneurship.

Conclusively, almost all the demographic and professional factors have a strong influence on SHG women entrepreneurship development.

Research Question 2: What are the key entrepreneurial attributes that affect SHG women microentrepreneurs' success?

Through the review of literature and personal observation, the researcher identified three entrepreneurial attributes of SHG women, which are entrepreneurial skills, avoidance of role-conflict skills and motivation-cum-risk-bearing attitude.

Entrepreneurial Skills: There is significant relationship between entrepreneurial skills and SHG women entrepreneurial success. It is further concluded that the higher the entrepreneurial skills, the higher the SHG women entrepreneurial success. This finding is supported by many studies like Gerber (2001) who reported that entrepreneurial skills, problem solving skills and managerial skills are important for the entrepreneurs (Rae, 2007).

Avoidance of Role-Conflict Skills: The current study found that there is a significant relationship between avoidance of role-conflict skills and SHG women's entrepreneurial success. Women tirelessly face several household demands and family responsibility, because they are still expected to be the primary caregivers and homemakers (Huang et al., 2004). To become successful entrepreneurs, the women have to avoid role-conflict. This finding is consistent with that of Ruderman et al. (2002).

Motivation-cum-Risk-Bearing Attitude: This study found that there is significant relationship between motivation-cum-risk-bearing attitude and SHG women's entrepreneurial success. It is further concluded that the higher the motivation-cum-risk-bearing attitude, the higher the SHG women's entrepreneurial success. This is consistent with the findings of Aravindha and Renuka (2002) who discussed the important factors such as self-interest and inspiration that motivate women towards entrepreneurship.

Research Question 3: Do the gender issues affect SHG women microentrepreneurs' success?

The current study found that there is significant relationship between gender equality and SHG women's entrepreneurial success. It is further concluded that gender equality can improve the level of SHG women's entrepreneurial success. The results of the present study are consistent with the findings of many researchers. Women entrepreneurs have long felt that they have been discriminated against by various social and cultural factors (Rajendran, 2003).

Hypothesis Testing

Relationship Between Entrepreneurial Skills and Avoidance of Role-Conflict Skills of SHG Women

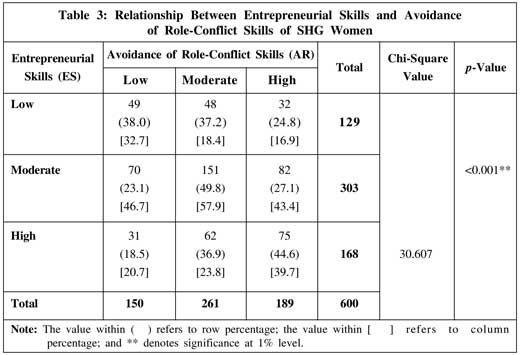

It is observed from Table 3 that out of 600 samples collected for the study, 49 (38.0%) perceived low ES and low AR and 70 (23.1%) perceived moderate ES and low AR. A good

number of respondents, i.e., 151 (49.8%), perceived moderate ES and AR, while 75 (44.6%) respondents perceived both high ES and AR. Since the p-value is less than 0.01, the null hypothesis is rejected at 1% significance level. Hence, it is concluded that the alternate hypothesis is accepted, i.e., there is significant relationship between entrepreneurial skills and avoidance of role-conflict skills of SHG women.

Relationship Between Entrepreneurial Skills and Motivation-cum-Risk Bearing Attitude of SHG Women

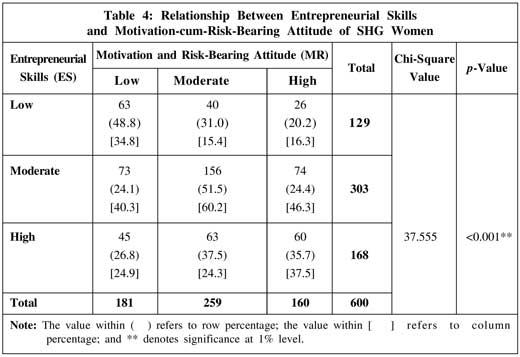

It is observed from Table 4 that out of 600 samples collected for the study, 63 (48.8%) perceived low ES and low MR and 73 (24.1%) perceived moderate ES and low MR. A good number of respondents, 156 (51.5%), perceived moderate ES and MR, while 60 (35.7%) respondents perceived both high ES and MR. Since the p-value is less than 0.01, the null hypothesis is rejected at 1% significance level. It is concluded that the alternate hypothesis is accepted, i.e., there is significant relationship between entrepreneurial skills and motivation-cum-risk-bearing attitude of the SHG women.

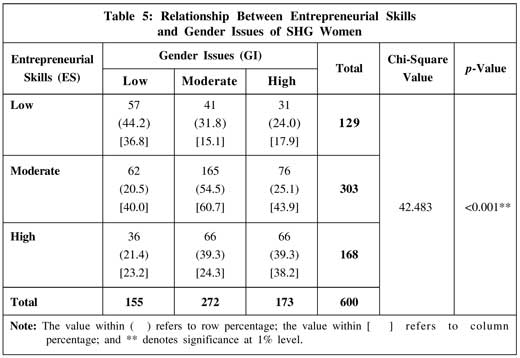

Relationship Between Entrepreneurial Skills and Gender Issues of SHG Women

It is observed from Table 5 that out of 600 samples collected for the study, 57 (44.2%) perceived low ES and low GI and 62 (20.5%) perceived moderate ES and low GI. A good number of respondents, 165 (54.5%), perceived moderate ES and GI. 66 (39.3%) respondents perceived both high ES and GI. Since the p-value is less than 0.01, the null hypothesis is rejected at 1% significance level. It is concluded that the alternate hypothesis is accepted, i.e., there is significant relationship between entrepreneurial skills and gender issues of SHG women.

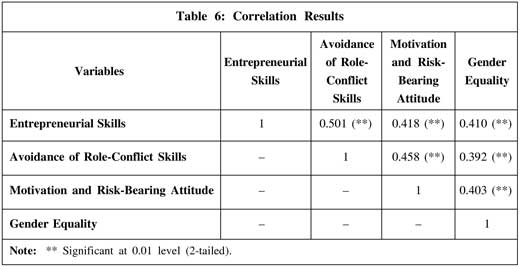

Table 6 presents the results of correlation test conducted among the variables used in the study.

Conclusion

This study aimed to empirically test and identify the factors involved in the process of SHG women entrepreneurial success. The study reveals the emerging need for key entrepreneurial skills, motivation-cum-risk-bearing attitude and gender equality through the sample survey of SHG women entrepreneurs in Chittoor district of Andhra Pradesh, India. Above all, the study demands participative approach and long-lasting commitment by all the stakeholders involved in the process. In India, SHG women are very large in number and have high potential, but are very slow in acquiring the skills and knowledge required for managing microenterprises. Hence, a stringent and specialized policy framework has to be made through governance and mentorship.

The study contributes to the knowledge and practice of entrepreneurial development through the following suggestions:

- It suggests that the growing challenges of entrepreneurial development system can be met by advocating and inculcating entrepreneurial competence and training to SHG women entrepreneurs; and

- The study highlights that the SHG women microentrepreneurs should overcome the important deficiencies related to access to skill development, risk-bearing attitude and gender equality to succeed.

Scope for Future Studies: This study provokes further research interest in the field of strategic entrepreneurship development on the following lines with an emphasis on women empowerment and women development:

- Some hidden contextual and vital factors influencing the progress of SHG women entrepreneurship development like individual contribution and socioeconomic practices may still exist. Thus, the study may be extended by identifying some more sources/factors of SHG women entrepreneurship development.

- This study does not cover the other impact factors such as marketing, cooperative management, leadership and manpower system, cost-related analysis, buy-back arrangement from medium and large-scale enterprises, etc. that directly influence women entrepreneurship. The study can be extended by considering these factors.

- Future studies may also investigate the barriers to the effective implementation of SHG women's microenterprise management system through a case study method.

References

- Aldrich Howard E and Cliff Jennifer E (2003), "The Pervasive Effects of Family on Entrepreneurship: Toward a Family Embeddedness Perspective", Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 18, No. 5, pp. 573-596.

- Aravindha and Renuka (2002), "Women Entrepreneurs – An Exploratory Study", Public Opinion, Vol. 47, No. 5, pp. 27-28.

- Bouman F J A (1995), "Rotating and Accumulating Savings and Credit Associations: A Development Perspective", World Development, Vol. 23, No. 3, pp. 371-384.

- Chandler G N and Jansen E (1992), "The Founder's Self-Assessed Competence and Venture Performance", Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 7, No. 3, pp. 223-236.

- Dann Susan (2000), "The Changing Experience of Australian Female Entrepreneurs", Gender, Work and Organization, Vol. 7, No. 2, pp. 12-20.

- Dhameja S K (2002), Women Entrepreneurs: Opportunities, Performance & Problems, p. 11, Deep Publications Pvt. Ltd, New Delhi.

- Gerber T P (2001), "Paths to Success: Individual and Regional Determinants of Self- Employment in Post-Communist Russia", International Journal of Sociology, Vol. 31, No. 2, pp. 3-37.

- Goyal Meenu and Jai Prakash (2012), "Women Entrepreneurship in India – Problems and Prospects", ZENITH International Journal of Business Economics & Management Research, Vol. 2, No. 5, pp. 56-65.

- Hisrich R D and Brush C G (1984), "The Woman Entrepreneur: Management Skills and Business Problems", Journal of Small Business Management, Vol. 22, No. 1, pp. 30-37.

- Huang Y H, Hammer B, Neal M B and Perri N A (2004), "The Relationship Between Work-to-Family Conflict and Family-to-Work Conflict: A Longitudinal Study", Journal of Family and Economic Issues, Vol. 25, No. 1, pp. 79-100.

- IKP-DRDA (2008), Notes for World Bank Mission, Chittoor, pp. 1-36.

- Jean Lee Siew Kim and Choo Seow Ling (2001), "Work-Family Conflict of Women Entrepreneurs in Singapore", Women in Management Review, Vol. 16, No. 5, pp. 204-221.

- Karmakar K G (2003), Rural Credit and Self Help Groups – Microfinance Needs and Concepts in India, p. 231, Sage Publication India Pvt. Ltd., New Delhi.

- Kurien Thomas (2003), "Andhra Pradesh Community Self Help Model", Centre for Good Governance (CGG) Collected Working Papers, pp. 1-16.

- Malcom Harper (1998), "Profit for the Poor", Cases in Micro Finance, Oxford Publication.

- Mc Elwee G (2008), "Taxonomy of Entrepreneurial Farmers", International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, Vol. 6, No. 3, pp. 465-478.

- Meredith G G, Nelson R E and Neck P A (1982), Practice of Entrepreneurship, p. 16, International Labour Office, Geneva.

- NABARD (1997), Micro Finance Innovations and NABARD, NABARD Publication, India.

- Newton Janice, Wood Glenice and Gottschalk Lorene (2003), "Motivation and Success: Mixed Motivations for Women in Small Business in Regional Victoria", Rural Society Journal, Vol. 13, No. 1, pp. 5-21.

- Ojha R K (2001), "Self-Help Groups and Rural Employment", Yojana, Vol. 45, No. 5, pp. 20-23.

- Otero M (1999), "Bringing Development Back, into Microfinance", Journal of Microfinance/ESR Review, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 8-19.

- Rae D (2007), Entrepreneurship: From Opportunity to Action, Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke.

- Rajendran N (2003), "Problems and Prospects of Women Entrepreneurs", SEDME, Vol. 30, No. 4.

- Rehman S and Muhammad Azam R (2012), "Gender and Work-Life Balance: A Phenomenological Study of Women Entrepreneurs in Pakistan", Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, Vol. 19, No. 2, pp. 209-228.

- Ruderman M N, Ohlott P J, Panzer K and King S N (2002), "Benefits for Multiple Roles for Managerial Women", Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 45, No. 2, pp. 369-386.

- Singh Ranbir (2012), "Women Entrepreneurship Issues, Challenges and Empowerment Through Self Help Groups: An Overview of Himachal Pradesh", International Journal of Democratic and Development Studies, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 1-14.

- Singh Sukhbir (2007), "Towards Inclusive Rural Financial Services – Microfinance in India", in Sangita Kamdar (Ed.), Microfinance, Self-Employment and Poverty Alleviation, p. 61, Himalaya Publishing House.

- Singh K and Jain T S R (1995), "Evolution and Survival of SHGs: Some Theoretical and Empirical Evidences", Working Paper No. 4, Bankers Institute of Rural Development, Lucknow.

- Srivastav A K and Chaudhary Sanjay (1991), "Women Entrepreneurs – Problems, Perspective and Role Expectations from Banks", Unpublished Thesis, Punjab University, Chandigarh.